China and the United States’ broad-spectrum global competition has increasingly transformed into a hostile rivalry. In the technological sphere, this has sparked growing discussions and accumulating steps on both sides toward so-called “technological decoupling” — a reduction in asymmetrical reliance or interdependencies and, in some cases, a complete severing of their ties in the technology and cyber spheres. With the acute impacts of this process between the two tech superpowers becoming clearer, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) is slowly emerging as an important region to watch. Economic and geopolitical ties with the West have long dictated the shape of the region’s digital environment, but more recent great power competition and Middle Eastern countries’ pursuit of economic and technological sovereignty have slowly deconstructed these dynamics.

Three key characteristics of the regional tech and cyber landscape are most likely to dictate its future form and dynamics over the coming years:

-

Cyberwar has become typical and recurrent in the Middle East because of the challenging geopolitics that characterize the region. As a result, actors must expand both their conventional and non-conventional toolboxes to achieve or maintain a preferable regional position. Cyberwarfare has a low threshold for entry and provides nation-states and non-state actors with a cheap method to realize their geopolitical aims without resorting to conventional military means.

-

MENA is experiencing a growing digital divide. The Gulf subregion (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates) has paved the way as a leader within MENA through investments in digital infrastructure, 5G, and the cloud. Following the Gulf is North Africa, where local countries are actively working to utilize their demographics and limited finance to build up their digital landscape. In contrast, the Levant (Iraq, Lebanon, Syria) is the subregion most affected by tech disparity and lags uncomfortably behind the both the Gulf and North Africa.

-

Digital and tech sovereignty are the new norms. The Gulf countries lead the way in the Middle East as they look to establish a more resilient tech ecosystem by investing in an Open Radio Access Network (RAN) to diversify the components of their 5G ecosystem and, thus, avoid the fallout from the U.S.-China tech cold war, build local supply chains, and pursue active data localization policies.

These characteristics are also closely connected to several risks to the regional tech landscape.

-

First, a digital transformation that would meet regional ambitions, specifically those of the Gulf states, would require the mobilization and maintenance of a digitally capable workforce. Sourcing this human capital in an era of intense competition for global talent remains a challenge for the region as a whole and, in particular, for the brain-drained Levant and North Africa subregions. A two-fold approach to building this digitally capable workforce is necessary, combining both access to digital literacy specialization at local academic institutions and importing experienced leadership teams able to motivate such a transformation. This approach presents local tech specialists, who have long been the target of global tech talent poaching, with an ultimatum: do they pursue prosperity abroad or invest in the future potential of their home countries? In the Gulf, a higher quality of life and a more developed technological environment make the latter a more attractive option. Alternatively, in North Africa and the Levant, underdeveloped technological environments, economic uncertainty, and political instability encourage the pursuit of better opportunities abroad. If the region fails to consistently source qualified human capital, MENA will find itself in an uncomfortable position as global tech decoupling continues to unfold.

-

Second, great power competition will continue to profoundly shape the regional digital landscape. Historically, great powers have shown an interest in maintaining their involvement in Middle Eastern supply chains, economic development initiatives, and geopolitical dynamics. These interests are not exclusive to regional technological architectures or capabilities. For decades, U.S. digital firms have worked on an expansive digital network connecting them to the Gulf and Israel. And more recently, Chinese big tech made heavy investments in MENA’s digital network and cloud computing infrastructure, indicating Beijing’s desire to solidify its role as a technological provider to the region. As the Middle East rises to the challenge of navigating the difficulties and opportunities opened up by the great tech decoupling, another question appears: Does the region remain committed to the “America first” policy championed in the past, or does it pursue novel ties with rival partners in an age of greater multipolarity? Fidelity to one would likely mean the desertion of the other. The various MENA subregions face the challenge of balancing such decisions against geopolitical considerations. The two divergent paths could mean vastly different futures for the landscape of digital transformation, especially in the realm of cyberwarfare and defense technology — yet another factor that will influence the decision-making processes of Middle Eastern leaders.

The second risk is perhaps of greater immediate concern than the first. The two biggest globalized economies — China and the U.S. — have decided that a Cold War 2.0 is the way forward. In this tense standoff, emerging economies could try to hedge their bets and build coalitions to weather the storm. Realistically, however, such a gamble will continue to be costly and filled with logistical obstacles and geopolitical landmines. Questions like who will source and build the region’s 5G/6G infrastructure will involve geopolitical calculations instead of pure economics.

The matter of semiconductors offers a useful case study. Late last year, the Biden administration imposed export controls on this industry to limit China’s access to advanced semiconductors, ultimately slowing down China’s tech growth and, most likely, chipping away at its reputation as a global leader in this particular sector. In order to avoid U.S.-imposed sanctions, Chinese companies have had to tweak their most advanced chip designs to reduce their processing speeds, thus suppressing Chinese computing power. Now, the Netherlands and Japan will abide by these controls. But the U.S. campaign will not be limited to semiconductors and 5G: it may soon expand to biotechnology and artificial intelligence (AI).

The U.S. and Chinese tech decoupling has ushered in an era of perpetual cyberwar and of a growing digital divide that exacerbates the challenges of finding a digitally capable workforce. Yet in all of this, MENA states are pursuing policies designed to build up the region’s digital and tech sovereignty. The most notable challenge for Middle Eastern and North African states will be navigating between the U.S. and its global rivals in such a way so that the repercussions of this great power competition do not hinder the region’s digital transformation efforts.

Mohammed Soliman is the director of MEI's Strategic Technologies and Cyber Security Program, and a manager at McLarty Associates’ Middle East and North Africa Practice. His work focuses on the intersection of technology, geopolitics, and business in the Middle East and North Africa.

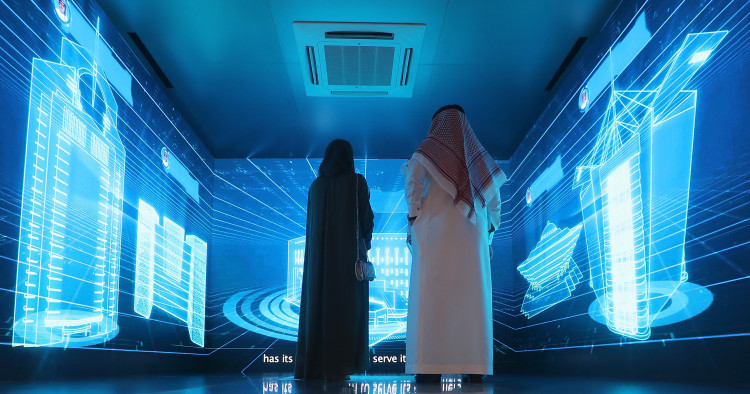

Photo by KARIM SAHIB/AFP

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.