International attention is heavily focused on the prospects of a so-called “megadeal” among Israel, Saudi Arabia, the United States, and, on the margins, the Palestinian Authority (PA). A successful resolution of the negotiations currently underway would encompass Saudi Arabia joining the Abraham Accords, normalizing its relations with Israel, along with commitments and obligations from each of the parties significantly affecting the fabric of regional politics, economy, and security. Speculation abounds over the potential elements of the deal, including access to U.S. security commitments, advanced weaponry, and civilian nuclear facilities for the Saudis, full diplomatic relations with the most important Sunni Arab country for Israel, and tangible benefits for the Palestinians coming from the three other parties to the negotiations. For the U.S., the agreement would strengthen its regional security framework and provide new evidence of U.S. political and diplomatic heft — a fitting riposte to those who perceive Chinese or Russian regional ascendency.

But what happens the day after the signing ceremony on the White House lawn? Will the benefits anticipated in the negotiations be realized? Will Saudi-Israeli normalization bring about a fundamental realignment of regional relationships and expand a new security and stability paradigm for the region? Will a Saudi deal open the way to a flood of follow-on normalization agreements? Perhaps most importantly, will Saudi-Israeli normalization provide reasonable assurance of a revitalized Israeli-Palestinian track to resolve their conflict, improve the lives of Palestinians, and open a pathway to a two-state solution?

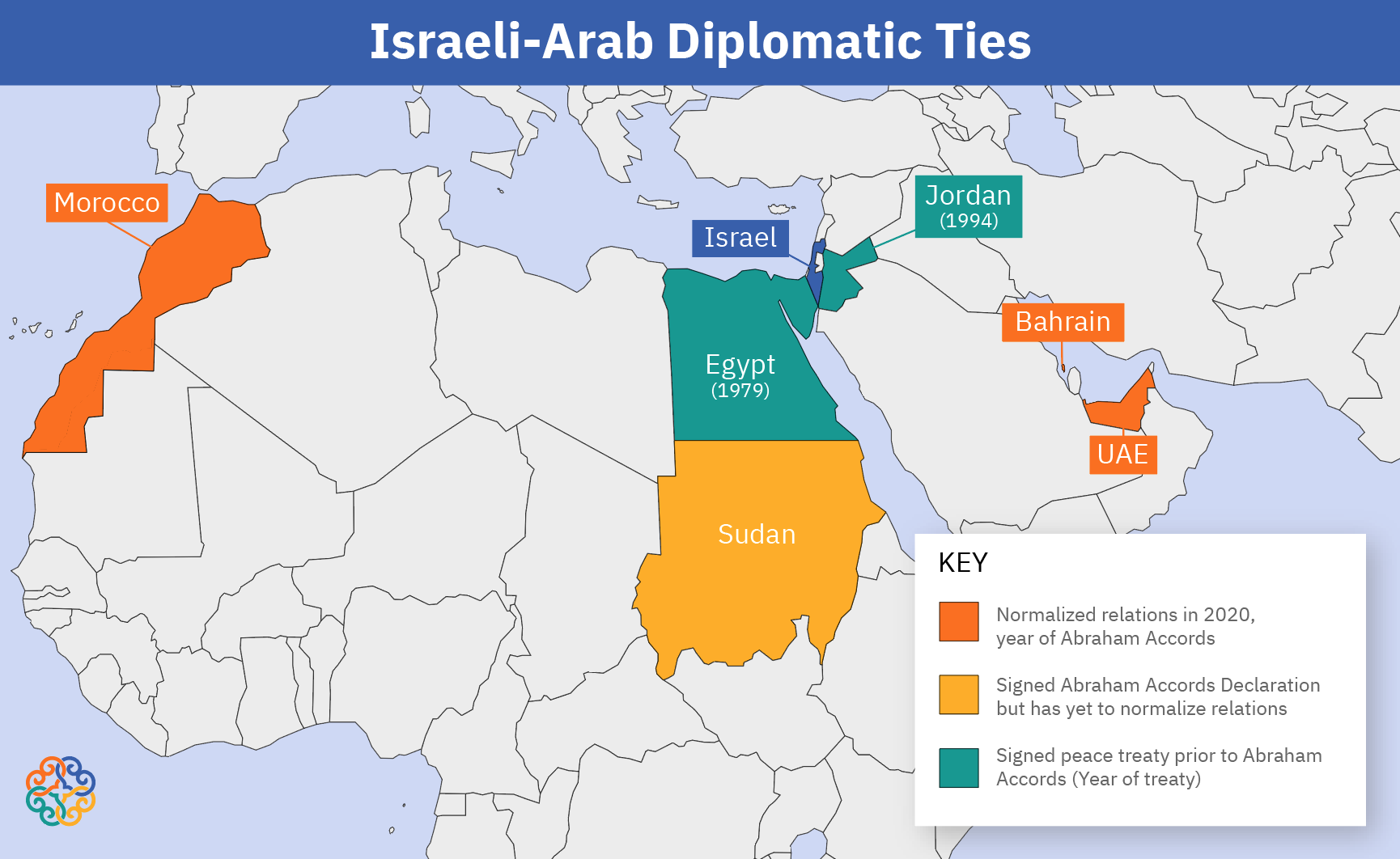

Fortunately, as the original Abraham Accords signatories — Israel, the United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain — observe the third anniversary of their September 2020 agreement, there is a sufficient basis to evaluate whether the Abraham Accords are real, hype, or something in-between. Much like the case a year ago, on the occasion of the Accords’ second anniversary, the results so far remain mixed. The parties have taken long strides toward actualizing their defense and security cooperation and laid at least a foundation for enhanced economic links. But the rise of a far-right extremist government in Jerusalem, deepening violence between Israelis and Palestinians, and deteriorating conditions for Palestinians in the West Bank, Gaza, and Jerusalem have set back relations, frozen the Negev Forum, as well as triggered a sharp decline in Arab popular opinion toward normalization. While not determinative for the fate of the Abraham Accords or negotiations to expand their scope, the hardening of Arab popular opposition to normalization will complicate the process going forward.

The view from 2020

In their joint declaration issued on the conclusion of the Abraham Accords, the signatories “warmly welcome[d] and are encouraged by the progress already made in establishing diplomatic relations between Israel and its neighbors in the region under the principles of the Abraham Accords. We are encouraged by the ongoing efforts to consolidate and expand such friendly relations based on shared interests and a shared commitment to a better future.” Joined by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and the foreign ministers of the UAE and Bahrain (Morocco and Sudan signed the Abraham Accords at a later date), then-President Donald Trump proclaimed that the Sept. 15, 2020, signing ceremony marked “the dawn of a new Middle East” that “will serve as the foundation for a comprehensive peace across the entire region.” Prime Minister Netanyahu similarly trumpeted that the Accords represented “a pivot of history” and “a new dawn of peace.”

For the UAE and Morocco in particular, the decision to sign the Abraham Accords was also accompanied by more tangible commitments from the U.S. side. The UAE anticipated that it would be able to acquire the top-of-the-line U.S. F-35 stealth fighter as well as MQ-9 Reaper drones following normalization. The Moroccans looked to Washington to recognize their sovereignty over the disputed Western Sahara in the hope that would break the stalemate over their claim. But neither Abu Dhabi nor Rabat has fully realized its aspirations. Despite Trump administration movement on the F-35 and Reaper sales, the extraordinarily complicated negotiations over the releasability of key components, along with U.S. doubts over the security of its technology in view of growing Emirati-Chinese relations, have stalled the process and led to an Emirati declaration that they were abandoning pursuit of the aircraft. Despite that Emirati declaration, talks are likely continuing, however. For Morocco, only Israel has followed the U.S. lead in recognizing its sovereignty in the Western Sahara, which the United Nations continues to list as a “non-self-governing territory,” while the International Court of Justice has ruled Morocco’s efforts to annex it as illegal.

The Accords have an impact

Notwithstanding the disappointment that the immediate anticipated benefits have not been fully realized, the conclusion of the Abraham Accords agreements has undoubtedly brought significant change.

Growing security cooperation

Israeli recognition of Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara earlier this summer opened the door to a substantial expansion of bilateral military and security cooperation, including the appointment of Israel’s first defense attaché to Rabat. Omer Dostri, a senior researcher at the Jerusalem Institute for Strategy and Security, told Al-Monitor in a July interview that Israeli-Moroccan bilateral security cooperation extends over three fields: intelligence cooperation, joint military exercises, and arms and technology trade. Israeli military units have participated for the first time in the U.S.-led African Lion military exercises in Morocco, while the Moroccans have purchased drones and air- and missile-defense systems from Israel and have reportedly expressed interest as well in acquiring Merkava armored vehicles and cybersecurity gear.

Given shared concerns over Iran’s aggressive activities in the Gulf region, that area has seen the greatest growth of Israeli defense cooperation, facilitated by its incorporation into the U.S. military’s Central Command (CENTCOM). As such, Israeli military personnel have a seat at CENTCOM multilateral security forums. Expanding on that growing Israeli role, Bahrain became the first Gulf country, in February 2022, to sign a bilateral defense cooperation agreement with Israel. The agreement references cooperation in intelligence, military-to-military relations, and industrial collaboration. As in other aspects of bilateral cooperation post-Abraham Accords, however, the UAE has demonstrated the greatest facility in achieving tangible outcomes from its new relationship. Earlier in 2023, the two governments demonstrated a jointly produced unmanned surface vessel during the Naval Defense and Security Exhibition (NAVDEX) in Abu Dhabi. Similarly, the Israeli company Elbit Systems announced that its Emirates-based subsidiary would provide the UAE Air Force with $53 million in defense systems, while Israeli and Emirati companies are jointly looking to produce a counter-drone system. Although the matter was not published, satellite images and reports in foreign media reveal that the UAE has also deployed the Israeli-made Barak aerial-defense system against Iranian/Houthi ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, and drones.

Trade and investment

As with security cooperation, the parties to the Abraham Accords have seen substantial growth in bilateral economic cooperation in the years since the agreement was signed. According to Bank of Israel statistics, Israeli imports from the region more than doubled, from $3.6 billion in 2019 to $8.3 billion in 2022. For the first four months of 2023, bilateral trade between the UAE and Israel was valued at $990.6 million, with an expectation that it would reach $3 billion for the year and $3.45 billion for 2024. Although Israel’s bilateral trade with Morocco and Bahrain lags far behind its trade with the Emirates, the parties are looking to a significant expansion of economic relations in the future.

To facilitate this process, each of the three Arab parties to the Abraham Accords has now signed bilateral trade and investment agreements with Israel. Morocco led the way in February 2022 with an agreement focused on development of bilateral trade, cooperation, customs exemptions for temporary imports (e.g., sample products for display or for art exhibitions), and implementation of steps to expand mutual trade relations. The UAE-Israeli free trade agreement came into force in April 2023. That agreement provides tariff relief for some 96% of products traded between the two parties and allows for the entry of UAE service companies into a range of Israeli markets while offering Israeli companies reciprocal access to UAE government tenders.

A free trade agreement between Israel and Bahrain, finalized at the professional level more than a year ago and expected to encourage trade between the countries, has not yet been ratified by the leaders. In September, however, on a visit to mark the opening of a new Israeli embassy chancery in Manama, Israel’s Foreign Minister Eli Cohen signed with his Bahraini counterpart, Abdullatif al-Zayani, a new agreement aimed at expanding tourism, increasing the number of direct flights between the two countries, and enhancing trade and investment links. Cohen was accompanied on his visit to Bahrain by a business delegation representing over 30 Israeli companies from the high-tech, logistics, and real estate sectors.

As is the case with security cooperation, the UAE has demonstrated that it is best positioned to take advantage of new trade and investment opportunities with Israel. Notably, in November 2022, the two signed an agreement with Amman to have an Emirati company build a 600 megawatt (MW) solar energy plant in Jordan, with the power sold to Israel; in exchange, Israel pledged to provide 200 million cubic meters of desalinated water to Jordan. In another notable initiative, the UAE company PureHealth announced that it is partnering with Israel’s Sheba Medical Center to promote research, medical tourism, training, and medical technology.

Figures from the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics show that while trade between the UAE and Israel in 2021-22 (excluding diamonds and services) amounted to about $2.5 billion, trade with Bahrain was worth only $20 million. The gap can be partly explained by the fact that the UAE is a global financial hub and, therefore, offers additional opportunities for trade. Thus, the figures also, and perhaps principally, reflect re-export of goods from other economies.

Tourism: A one-way street so far

All of the Abraham Accords parties have identified tourism as a potential core element in the expansion of both bilateral economic activity and promotion of greater people-to-people exchanges. It’s now possible to travel directly between the UAE, Bahrain, and Israel. Emirates Airlines has announced that it would increase its Tel Aviv-Dubai flights to three times weekly. Direct travel between Tel Aviv, Casablanca, and Marrakesh has been established since the signing of the Accords, but the Israeli airline Arkia has announced that it will begin service to a third destination, Essaouira, in September. Essaouira, on the Atlantic coast, is renowned for its beach resorts but is especially popular with Israeli visitors as an historic center of the Moroccan Jewish community.

Despite the interest of the parties in promoting tourism, the flow of travelers has primarily been one way. In 2022, some 268,000 Israelis visited the UAE and 200,000 more arrived in Morocco. Even with relaxation of visa requirements, however, only around 2,900 Moroccans visited Israel during that same time period, and only 1,600 Emiratis traveled to Israel, while the number of Bahraini visitors last year was 400. Tensions in Israel, especially Jerusalem, and the Palestinian Territories have discouraged Gulf Arab visitors; nonetheless, there has been a concerted push by Israeli tourism officials to promote travel to the country, including a visit to Bahrain by Israeli Tourism Minister Katz.

The Negev Forum: Failure to launch

Although the focus of commentary on the Abraham Accords has been in the security, trade, and investment realms, the declaration of the signatories in 2020 was far more ambitious. In particular, the parties asserted their desire to “support science, art, medicine, and commerce to inspire humankind, maximize human potential, and bring nations closer together.” Regional security, particularly in response to Iran’s nuclear program and regional aggression, was at the center of the first Negev meeting in March 2022. Representatives of four Arab countries (the UAE, Bahrain, Morocco, plus Egypt) along with U.S. and Israeli representatives, met at Sidi Boker in the Negev Desert. Beyond security, the parties agreed to regularize the gathering as an annual meeting, the Negev Forum, and expand the agenda to include economic and diplomatic cooperation. To that end, the six foreign ministers together decided to establish working groups in the fields of education, health, energy, tourism, food, and water.

The first meeting of the Negev Forum Working Groups was hosted by the UAE in January 2023 and advanced a discussion of initiatives to encourage regional integration, cooperation, and development, including efforts to strengthen the Palestinian economy and improve the quality of life for the Palestinian people. The Steering Committee also released the agreed Negev Forum Regional Cooperation Framework to codify the structure and goals of the Forum and build networks of cooperation. The Framework reiterated that a key objective would create momentum toward a resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Since that meeting, however, further progress has stalled. Morocco had proposed to chair the next meeting of the Negev Forum summit in Dakhla in March 2023, but the advent of the far-right Israeli government in December 2022 and the deterioration of conditions in the Palestinian Territories and Jerusalem has led to a series of postponements of the forum. The most recent postponement came in July. The Moroccan decisions to put off the meeting came especially in response to announcements of the new government in Jerusalem regarding settlement expansion and the designation of the extremist finance minister Bezalel Smotrich as the minister responsible for planning approvals for settlement construction. No new date for the summit has been announced.

In the meantime, the U.S. has expressed interest in adding additional members to the Negev Forum, potentially including Jordan, the PA, and African representatives. Consideration is also in train to rename the platform, perhaps as the Association of Middle East and North African Countries — Peace and Development (AMENA-PD). At this juncture, however, next steps for the Negev sextet are in abeyance, depending on the political direction in Jerusalem and the state of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Arab popular opinion on normalization has not improved

The violent response in Libya to reports that the country’s foreign minister, Najla Mangoush, had met in late August with her Israeli counterpart, Eli Cohen, in Rome is indicative of the current sour mood of Arab publics toward normalization with Israel. An overwhelming 96% of Libyan respondents to the Arab Opinion Index 2022, as reported by the Arab Center in Washington, D.C., expressed opposition to normalization with Israel even prior to the controversial meeting in Rome. Collectively, 84% of those polled in 14 Arab countries between June and December 2022 expressed opposition to their governments’ normalizing relations. This included 38% of Saudi respondents, with only 5% supporting normalization.

The sharp decline in support for the Accords over the years extends as well to populations in the three Abraham Accords countries: when they were signed in 2020, about 40% of Bahrainis and Emiratis held a favorable view, but in subsequent polls this rate fell by half. In the Arab Opinion poll, only 20% of Moroccans agreed with their government’s recognition, while 67% opposed it. A separate poll reported by the Washington Institute for Near East Peace (WINEP) reflected as well the decline of popular support for normalization among Bahrainis, from 45% approval in November 2020 to just 20% in March 2023.

Arab popular responses to the Arab Opinion Index also clearly refuted suggestions that the Abraham Accords agreements removed the Palestinian issue as a concern or degraded its salience among Arab populations. When asked to cite their reason for opposing normalization with Israel, nearly 50% of respondents attributed their position to the Israeli occupation and oppression of Palestinians. Another almost 20% named racism toward Arabs, citing Israel as an enemy of Arabs, to explain their position. Even among those 8% of respondents who were open to normalization, nearly half made their acceptance conditional on the establishment of an independent Palestinian state.

While popular disapproval of normalization in the Arab world is not inevitable, the rise of the far-right government in Jerusalem, its antagonistic posture toward Arabs and Muslims, as well as increased violence in the Palestinian Territories and Jerusalem have significantly exacerbated long-standing opposition to recognition of Israel by Arab populations. The governments that have signed the Abraham Accords (or are negotiating currently) are not necessarily sensitive to public opinion in their countries; nevertheless, continued negative reports from Israel and the Palestinian Territories about Israeli actions, anti-Palestinian violence, and perceived assaults on Muslim holy places will make sustaining the normalization drive more difficult, as witnessed by Morocco’s decision to postpone Negev Forum meetings.

Conclusion

As the Biden administration’s attention on the Abraham Accords is consumed by efforts to add more members to the pact, most notably Saudi Arabia, further effort needs to be directed at ensuring that the Accords, as they exist today, are perceived by the signatory governments and their populations in a positive light. The results after three years present a mixed picture. Undoubtedly, the Accords have provided a foundation for enhanced cooperation among the parties in the security arena and offer at least the potential to expand bilateral trade and investment opportunities. For Israelis, the Accords have made accessible a part of the world long closed off to them. But the agreements do not operate in a vacuum and cannot be sustained in the absence of advancing on other issues of governmental and popular concern. The centrality of the Palestinian issue in the minds and hearts of the Arab people is clear. In February 2021, in a panel presentation hosted by WINEP, the Emirati ambassador to the U.S., Yousef al-Otaiba, explained his country’s decision to sign the agreement: “The truth is that the Abraham Accords were about preventing annexation. The reason it happened, the way it happened, at the time it happened was to prevent annexation,” referring to potential Israeli annexation of settlements in the occupied West Bank. At a moment when the potential for Israeli settlement expansion and annexation is once again being widely bruited among Israeli political leaders, it would be wise for the parties, especially the U.S. and Israel, to bear Otaiba’s comments in mind if they want to see the Accords become, as Netanyahu believed in September 2020, “a pivot of history” and “a new dawn of peace.”

There are many reasons to be skeptical about the prospects for a successful conclusion to the current Saudi-Israel-U.S. negotiations and obstacles abound. It is possible that a Saudi-Israeli agreement could provide the key to unlocking progress on the broader regional agenda needed to build a solid foundation for the Abraham Accords over the long term, more specifically on the Palestinian issue. Reporting and expert opinion on the matter is quite mixed, yet many expect Palestine to command a more central role in the talks between Saudi Arabia and Israel on normalization, contrary to the earlier assessments or expectations of the Israeli government. Three main reasons account for this: the importance of the issue for Saudi Arabia as the leader of the Arab-Muslim world; the demands that the Biden administration is expected to present to Israel to preserve the two-state option; and the understanding by PA President Mahmoud Abbas that he can gain more than he loses if he joins the move, contrary to his position regarding the earlier Abraham Accords negotiations.

In fact, in comments at an Atlantic Council event on Sept. 13, the UAE’s Ambassador Otaiba alluded to the centrality of the ongoing Saudi-Israeli-U.S. negotiations for the Israeli-Palestinian issue. He suggested that only the prospect of further expansion of the Abraham Accords could prevent what he described as Israel’s “de facto annexation” of the West Bank. Explaining that the 2020 commitments to the UAE on annexation (which came from the U.S., not Israel) only covered a period until 2024, Otaiba suggested that any new agreement to prevent annexation is “up to now future countries if they are to take that particular approach, but there’s very little that the UAE can do at this moment to shape what happens inside Israel.” Still, whether the Saudis are sufficiently determined to demand such an agreement and whether the current Israeli government is sufficiently interested in a deal with the Saudis to agree to one (and abide by it) is far from certain.

Amb. (ret.) Gerald Feierstein is a distinguished senior fellow on U.S. diplomacy at the Middle East Institute (MEI) and director of its Arabian Peninsula Affairs Program.

Dr. Yoel Guzansky is a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS) and a Non-Resident Scholar at MEI, specializing in Gulf politics and security.

Photo by Yuri Gripas/Abaca/Bloomberg via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.