The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region is grappling with many challenges on several fronts. Air pollution, water scarcity, and climate change in general are some of the serious challenges facing the MENA economies and residents that have been overshadowed by energy, security, and political debates surrounding the region. Nonetheless, considering their significant negative impact on the economic development of the MENA countries, inclusive, sustainable, and stable economic growth will require timely and effective solutions for the region's environmental challenges.

Air pollution is costing the MENA region 2.2% of its GDP

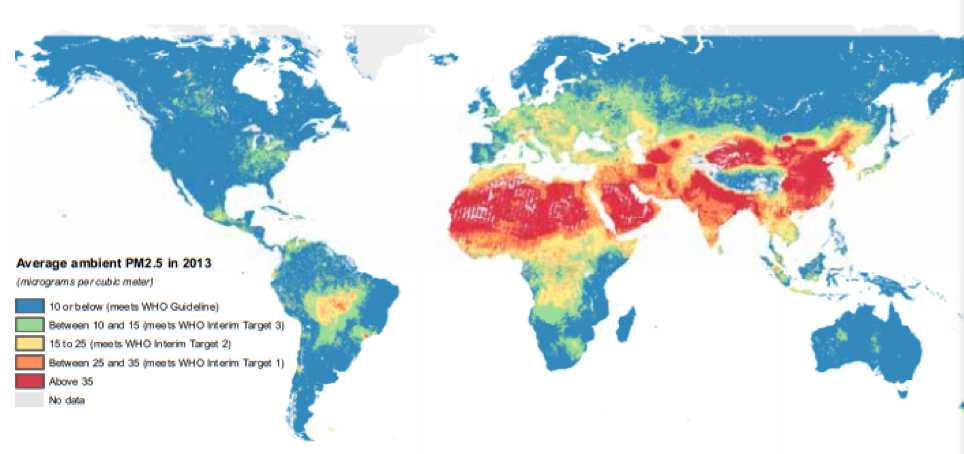

Eight MENA countries — Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE — are home to 29 of the 100 most polluted cities in the world according to PM10 concentrations. As seen in Figure 1, well over 90% of the MENA region has PM2.5 concentration levels that are above World Health Organization (WHO) air quality guidelines. According to the most recent figures, air pollution is estimated to have cost the MENA region around 2.2% of its GDP, which translates to $80 billion in 2019 alone.[1] Moreover, annually around 127,000 premature deaths are attributable to diseases associated with air pollution in the region. Multiply this number many times over and one arrives at the number of terminally ill linked to air pollution in the MENA region.

Figure 1. Locations Where 2013 Annual Average PM2.5 Concentrations (µg/m3) Meet or Exceed WHO Air Quality Guideline or Exceed Interim Targets

Desalination is ruining the environment of the Persian Gulf region

Water scarcity has been an inseparable part of the region for centuries, but the situation has become more severe in recent decades, increasing the likelihood and frequency of conflict over the limited water resources. Average renewable fresh water resources in MENA is around 444 cubic meters per capita per year, which is significantly below the U.N. water scarcity limit of 1,000 cubic meters per capita per year. A World Bank report estimates that by 2050, the economic loss from climate-related water scarcity is somewhere between 6% and 14% of the GDP. Clearly, such astronomical environmental costs seriously undermine the long-run health of any economy, including those in MENA.

The situation is more critical for Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, where desalination plants meet more than 15% of their potable water demand. The demand for drinking water is only expected to increase in the GCC as the population is forecast to grow from around 60 million in 2021 to over 80 million by 2050. As traditional sources of water such as rainfall, surface, and underground water reserves have fallen far short of meeting the region's growing demand for water, installing more desalination capacity remains the only viable solution for these economies, with heavy costs for the environment. Desalination is an energy-intensive procedure that leads to the emission of greenhouse gases and regional/global warming, further exacerbating drought and water scarcity conditions facing the region. Moreover, the byproduct of any desalination process is a hypersaline concentrate, referred to as “brine.” Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the UAE, and Qatar are responsible for 55% of total global brine production, which is dumped back into the Gulf. Among the Gulf countries, Saudi Arabia and the UAE are by far the world’s largest brine producers, accounting for more than 22% and 20% of the global brine, respectively. This practice has led to increasing salinity of the Persian Gulf and harming its ecosystem, fisheries, and organisms while at the same time increasing the energy requirements for desalination. Hence, meeting the freshwater demands of the Gulf countries through desalination comes with significant negative environmental consequences, the cost of which is not factored into the price of drinking water in the GCC.

Reducing and eventually removing all energy and water subsidies is central to any holistic strategy around MENA’s environmental challenges

There is no silver bullet to address the growing environmental challenges facing MENA economies, and a multifaceted strategy is required to slow down and reverse the pace of environmental degradation in the region. A crucial piece of such a strategy, however, is reducing wasteful usage of energy and water resources and promoting efficiencies on these fronts. Reducing energy and water subsidies is an important step in this direction.

Massive energy subsidies have been the hallmark of economies in the region and are the main cause for the wasteful usage of various resources. According to a 2019 IMF report, energy subsidies in the MENA region constitute around 13% of the region’s GDP, with a staggering figure of $111 billion for Iran, or 25% of its GDP. Water is also heavily subsidized as the region is home to some of the lowest water tariffs in the world. MENA consumers pay less than 35% of the cost of production of drinking water from surface and groundwater sources and only 10% of the cost of desalinated water. The rest of the bill is picked up by the state, which is costing the MENA economies around 2% of the GDP of the region, the highest in the world. These subsidies are wasteful and unjust as the region’s wealthiest households are their main beneficiaries. Thus, while energy and water subsidies are often justified as a poverty alleviation measure, they feature significant "benefits leak" to the wealthy.

As a result of such massive subsidies, 10 MENA countries have per capita electricity and water consumption levels higher than the world average, highlighting the wasteful and inefficient nature of electricity and water consumption in the region. For example, Qatari citizens enjoy free use of domestic water and electricity for one dwelling while non-Qatari residents also enjoy heavily subsidized services. Without a doubt, increasing tariffs to the level of world averages would reduce electricity and water consumption in MENA, improving air quality and reducing environmental damages linked to desalination and excessive underground water usage. At the same time, the government savings from the reduction or removal of such massive subsidies can, in turn, be channeled toward subsidizing the R&D of wind and solar energy, which have tremendous unrealized potential in this part of the world. The same is true with subsidizing R&D of atmospheric water generators (AWGs), which have incredible potential — given the high heat and humidity in much of the MEA region — in meeting the demand for drinking water while having a much smaller environmental footprint than various desalination technologies.

Over the past decades, having access to clean air and environmentally safe drinking water has turned into a luxury for hundreds of millions in the MENA region. Environmental sustainability can no longer be an afterthought when it comes to investment and policy. Rather, it should be an indispensable part of any such decisions. The popular view that addressing climate change comes at a net cost to the economy is no longer true because, as briefly highlighted above, environmental degradation directly undermines long-run economic development and prosperity by imposing significant costs on the economy. It is long overdue for policymakers, business leaders, and consumers in the MENA region to acknowledge the fact that environmental sustainability is a necessary — but not sufficient — requirement for the region’s inclusive, long-run, and stable growth.

Amin Mohseni-Cheraghlou is an assistant professor in the Department of Economics at American University in Washington D.C. His areas of expertise are development macroeconomics, energy economics, Islamic economics and finance, and MENA economies. The views expressed in this piece are his own.

Photo by Gehad Hamdy via Getty Images

[1] Some estimates put the cost as high as 4% of the GDP or $146 billion in 2019.

[2] Brauer, Michael, Greg Freedman, Joseph Frostad, Aaron van Donkelaar, Randall V. Martin, Frank Dentener, Rita van Dingenen, et al. 2016. “Ambient Air Pollution Exposure Estimation for the Global Burden of Disease 2013.” Environmental Science and Technology 50 (1): 79–88.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.