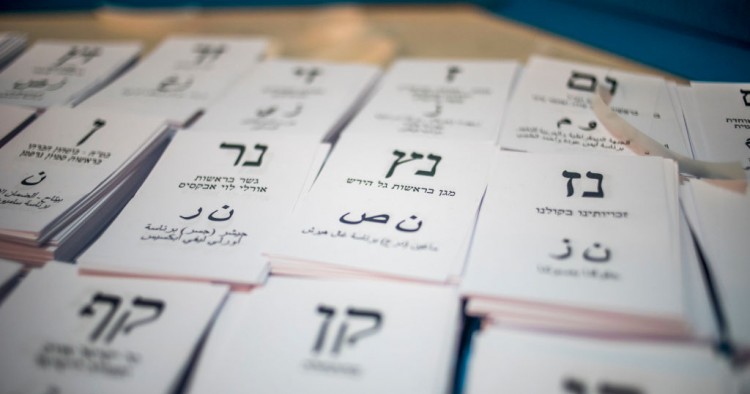

Jan.15, 2020 was the last date to submit electoral “lists” for the Israeli election scheduled for March 2. If you think you’ve heard a lot about Israeli elections recently, you’re not having déjà vu; in fact this is the third Israeli general election in less than 11 months. The previous two were so evenly split between the “Left” and “Right” blocs that no governing coalition could be formed. While there are still more than six weeks till the election — and an equal length of time after that before any government coalition is likely to be formed — this article will examine the political actors who will contest the election, with particular attention to those on the left and right ends of the spectrum. A flurry of parties on both ends were registered in the days before the Jan. 15 deadline, and some of their leaders may well be part of and influence the Israeli government that will (eventually) be formed.

The “Left” bloc is now composed of the centrist Blue-White party, the Labor party (now including Meretz as its left flank), and the Joint List (primarily Arab). It faces off against the “Right” bloc, composed of the right-wing Likud, the “ultra-Orthodox” (Haredi) United Torah Judaism and Shas parties, and (as of Jan. 15) the far-right Yamina (Rightwards) party, containing both religious and secular factions, and the farther right (Kahanist) Otzma Yehudit. The two previous elections and current polls indicate each bloc is likely to win 54-57 seats in the 120-member Knesset. The balance of power, i.e., the remaining 8-9 seats, are likely to be held by the rightist but anti-Netanyahu Yisrael Beiteinu party, headed by Avigdor Lieberman. Another deadlock is possible unless a few individual Knesset members or a party changes its fundamental stance.

Unlike previous Israeli elections, or the general European model, there are now no unaligned parties which might swing one way or the other. The main issue in this set of elections is Benjamin Netanyahu himself — now indicted on counts of fraud, breach of trust, and bribery — and all parties have long since staked out positions of absolutely supporting or opposing him

Israeli politics are not supposed to work that way. Traditionally there are fringe groups on the far right, such as followers of the late Rabbi Meir Kahane (assassinated in 1990), now in the Otzma Yehudit party, who have been considered beyond the pale, while on the “left” (in Israeli political terms) there have generally been several very disparate, predominantly Arab (Palestinian citizens of Israel) parties, ranging from Communists to Islamists. These parties have never been part of any governing coalition, with the partial exception of Yitzhak Rabin’s 1992-95 government, when the “Arab parties” kept it afloat from the outside. As Israeli politics have polarized into solid “Left” and “Right” blocs, support from these fringe groups has become essential in order to have any chance of forming a government.

This process was also hastened by a law passed before the 2015 election that raised the minimum (threshold) percentage for a party to enter the Knesset to 3.25 percent. If it does not reach that percentage, its votes are not counted, which can make all the difference for an entire bloc in a close election. The right might have been able to form a government in April had not one of its parties missed the threshold by three-hundredths of one percent.

Parties were frantically coalescing before Jan. 15, both to remain viable for their own agendas, and now urged on by the larger parties in each bloc, which need every vote they can muster. For example, on the right, PM Netanyahu was strongly pressuring the Yamina party to take in a smaller party (Jewish Home) that itself included the Kahanist faction, Otzma Yehudit. This was fiercely resisted by Yamina’s leader, current Defense Minister Naftali Bennett, who, despite his own support for annexation of settlements, doesn’t want to be associated with Kahanism, i.e., racism. Bennett won, when he pulled in the Jewish Home Party without the Kahanist Otzma faction, which is now running independently and may or may not reach the threshold.

Meretz has proudly proclaimed itself as the flagship of the Zionist left since 1992, when it won 12 seats and formed a government with Rabin’s Labor Party, which had 44. Now both parties, especially Meretz, faced possible extinction; in September’s election Labor garnered 6 and Meretz a pitiful 5. Labor’s leader, Amir Peretz, was hoping to win centrist voters turned off by Meretz, but finally bowed to pressure from almost everyone and created an electoral partnership with Meretz. A Jan. 14 poll showed the combined party receiving 10 seats — not great, but at least comfortably above the 3.25 percent threshold, below which looms political oblivion. The Joint List could barely conceal its glee; it hopes thousands of Arabs and also leftist Jews, disgusted with Meretz’s perceived shift to the right, will choose to vote for it as an alternative, and hopes to emerge with a record 14-15 seats.

The general rightward shift, plus rumors that President Trump’s “deal of the century” peace plan may be released before the election, could have been what prompted Blue-White leader Benny Gantz to announce on Jan. 21 that he too favored annexation of the Jordan Valley. This may have been encouraged as well by the Meretz-Labor partnership on his left that could be used as a bargaining chip in future negotiations, so he felt he could make a play for some of Netanyahu’s pro-annexation followers. His gambit seems to have failed; neither leftist nor rightists believed he would actually implement annexation.

Victory for either bloc, reliant on its “fringes,” could radically affect the next government’s priorities. On the one hand, Blue-White dependent on the Joint List might make peace overtures to the Palestinian Authority, or legislate significant changes in the status of Arabs within Israeli society. On the other hand, far-right parties might demand that Likud annex parts of the West Bank (already broached by Netanyahu) and a flood of new settlements. Or, Likud and Blue-White might form a coalition of their own, possibly led by Netanyahu or else pushing him aside, leaving him to the tender mercies of the State Prosecutor’s Office. Stay tuned!

Paul Scham is a scholar at MEI and the executive director of the Gildenhorn Institute for Israel Studies at the University of Maryland, where he teaches courses on the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The views expressed in this article are his own.

Photo by Bruno Thevenin/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.