The digital space has not only enabled claims to online avatars or alter-egos, it has also ushered in new forms of digital ownership. The explosion of the online marketplace is changing the ways in which art is created, perceived, and owned. If post-internet art propelled artworks into immateriality, Cryptoart, which uses blockchain technology, is creating a new generation of art collectors. For instance, 2017 saw the rise of collectible CryptoPunks, pixelated punk rock characters, and CryptoKitties, virtual cartoon cats that can be bought, sold, and bred. Sales of Cryptoart have leaped from over $416,000 in June 2020 to $616 million in the past year, based on data from cryptoart.io, which tracks sales across six auction houses. This kind of art increasingly relies on decentralized, global cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, which emerged in 2009.

Everydays: The First 5000 Days by Beeple (aka Mike Winkelmann) is widely cited as the first headline-grabbing digital artwork sold by a major auction house (Christie’s) for more than $69 million in March 2021 as a non-fungible token (NFT). Beeple’s record-setting monumental collage took 13 and a half years to make. Comprising 5,000 artworks, its sale came after his work Crossroad — a gif of people walking by an image of a dead, inflated, and graffiti-covered Donald Trump — which sold for $6.6 million in February.

How it works

Both Bitcoins and NFTs make use of the same underlying technology, blockchain, but Bitcoins essentially operate like cash, where each Bitcoin is fungible (i.e., interchangeable), while NFTs are indivisible and function as a digital record of ownership. As each NFT represents an individual artwork, with the artist’s signature and proof of any sale or transfer built into the code, their singularity has become the main selling point. An NFT is the cryptographically secure data that points to the digital file, which is hosted on a particular site. It represents the original artwork, as opposed to a copy that can be duplicated or downloaded. In essence, for the first time it allows for clear ownership of a digital asset.

If it seems radical that today art can be sold as a unique asset in the form of a jpeg, png, gif, mp4, or even a tweet, one can think back to the issues surrounding digital art as a medium in the 1960s in terms of easy reproducibility and the difficulty in assessing provenance and value. NFTs also reference processes of authentication that are verifiable on blockchain platforms, where provenance is encoded in a smart contract defining the conditions of transfer. Only one person can claim ownership, conferring the perception of scarcity and therefore, value. Significantly, they are considered a game-changer for artists, who are able to receive a cut every time their work changes hands (which doesn’t happen in the real world’s secondary market) and also maintain all intellectual and creative rights.

Present the Future

Critics believe that even if art-derived NFTs are forming a bubble that will eventually burst, they gesture toward the immense potential of digital artifacts that live online, providing an alternative to our current economic systems around art. At an artist talk at the Grand-Hôtel du Cap-Ferrat in the French Riviera announcing a new art residency, Present the Future, which took place there in June, art dealer and auctioneer Simon de Pury spoke about a world in which the old gatekeepers are no longer relevant, a time when the physical world needs to keep up with the digital sphere. This is a world of hybrids, where art and tech, music, and animation are linked to a single token. “Who said that the worlds of fashion, music, and art don’t go together?” says Kamiar Maleki, a London-based Iranian collector, Volta art director, and curator of Present the Future, which configures yet another NFT hybrid of performance and painting. It’s an extension of Maleki’s curatorial research: In 2015, he curated the exhibition Hashtag Abstract at London’s Ronchini gallery, commenting on the fluidity of digital art and how internet culture was affecting the way art is viewed and collected. Showcasing gestural works that could be sold both through the gallery and via social media, Maleki was inspired by the first work he bought by Kasper Sonne, via Instagram.

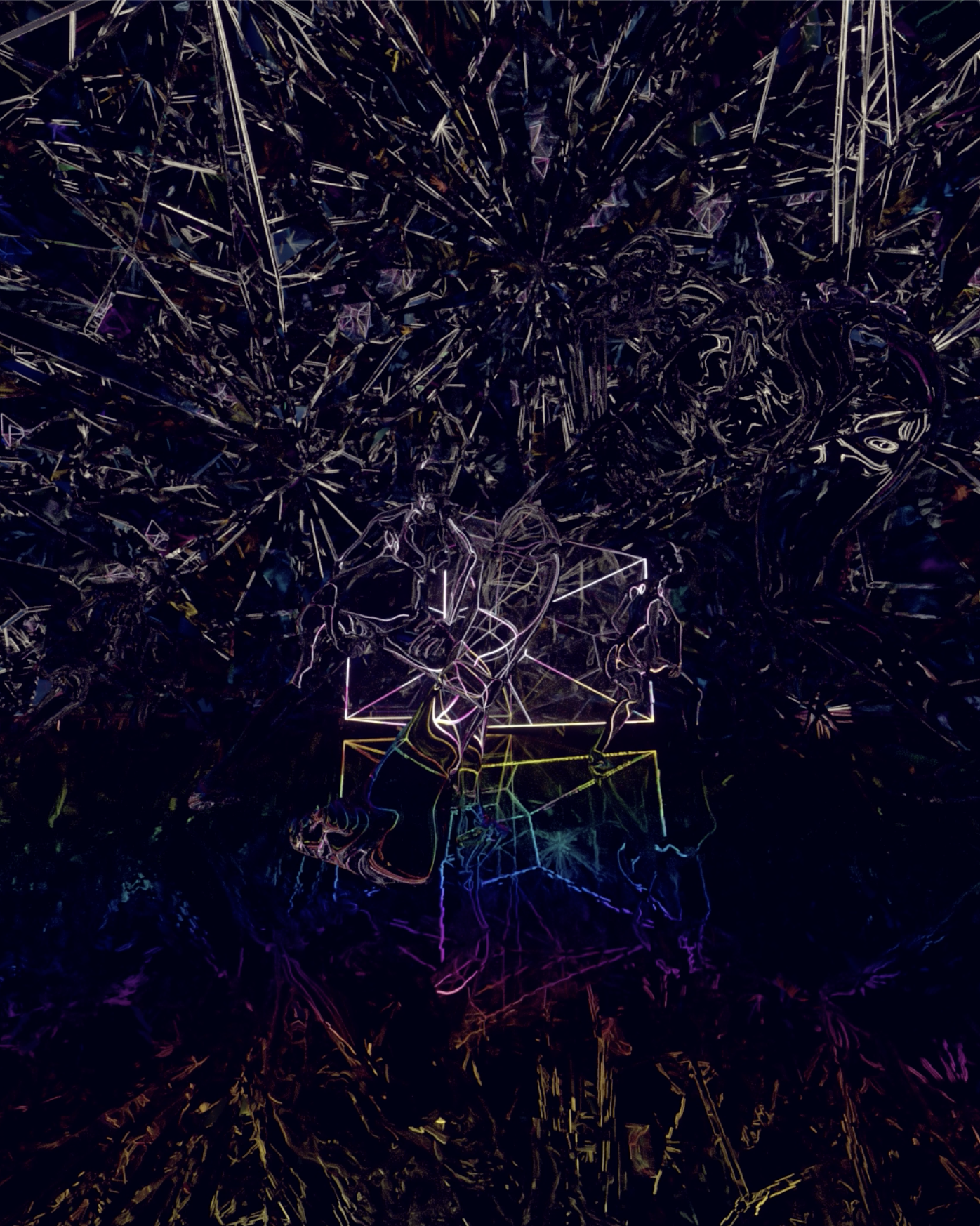

He has now brought together Côte d’Azur-based French-Iranian artist Sassan Behnam-Bakhtiar with London-based rapper-composer Tinie Tempah and digital artist Vector Meldrew to collaborate in this residency. Ranging from a performance on June 12 that paired Bakhtiar’s live painting with Tempah’s singing to a 90-second video produced by Vector Meldrew inspired by Bakhtiar’s paintings and Tempah’s lyrics, seven NFTs will be sold on July 21 in a drop on the platform Nifty Gateway, which in March began a partnership with Sotheby’s.

“I started on the internet 20 years ago, which was exciting because people were still figuring things out,” Meldrew explains. “But then things got weird around social media platforms with the data being used against us. NFTs really changed this as a whole ecosystem based on the idea of sovereignty. It is like a punk movement, where there’s hope for the future again because the power is taken away from the manipulations of centralized service providers. Cryptoart is leading this revolution,” he continues. As someone who began recording London’s underground music scene on websites and radio stations when he was just 16, Meldrew understands counterculture. His visuals for the Present the Future NFTs are sci-fiesque and fantastical: Tempah’s face looms large like a monumental statue, Bakhtiar’s flowers fragment into fractals, and hooded men wear shiny athletic gear.

Tempah’s song is inspired by Bakhtiar’s works, which often deal with energy, interconnectivity, and nature. The paintings he produced during the residency are an aesthetic departure from his more recognizable hazy abstractions and pulsating grids of shifting color. “Energy is a window of what exists within and outside us,” Bakhtiar says. “This work is about creating a bridge between our environment, the real world, and the virtual one.”

While the format of taking a live performance emerging from a site-specific residency and transforming the results into an NFT that’s minted (the computational process that registers it on the blockchain so it can be sold online) is unusual, this isn’t the first time that an NFT incorporates physical and digital components. Notably Khaled Jarrar’s animated If I don't steal your home, someone else will steal it unfurls as a series of Israeli settlements across a valley in the West Bank in a limited edition NFT that comes with jars of soil from Ramallah.

Environmental futures

It seems as if engaging with NFT art at all is a political statement (overt or not) indicating a tech-utopian belief in the decentralization of the internet, where information is verified and stored by all the computers on the network, rather than a single governing body. Yet this masks an environmental cost tied to a computer-intensive infrastructure of server farms, which, powered by electricity, convert cheap fossil fuels to valuable cryptocurrencies. The annual energy consumption from cryptocurrency mining (the act of running the computers) has been compared to that of sustaining an entire country.

In this democratized world, it will take a massive consensus to make the system more efficient and reduce its environmental footprint. Nevertheless, NFT art does signify a major cultural shift. Like the beginnings of net art, it’s still at an experimental stage where anything goes — though while it’s true that anyone can put an NFT up for sale and the barriers to entry are low, artists still need to be part of a network to be accepted into some of the selling platforms.

This is a space that attracts digital artists influenced by glitches, memes, and games as well as cryptomillionares investing in tech. It represents both art’s separation from its physicality and its simplification by digital consumption. The trick is to learn how to tell a different story, whether it’s a hopeful one like Present the Future, or more incisive social commentary.

Nadine Khalil is an independent arts writer, researcher, curator, and content specialist. The opinions expressed in this piece are her own.

Top photo: Tinie Tempah and Sassan Behnam-Bakhtiar attend Present The Future, a groundbreaking new project featuring a performance by Sassan Behnam-Bakhtiar & Tinie Tempah, on June 12, 2021, at the Grand-Hotel du Cap-Ferrat in Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat, France. Photo by David M. Benett/Dave Benett/Getty Images for Sassan Behnam-Bakhtiar

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.