This essay is part of the series “All About China”—a journey into the history and diverse culture of China through essays that shed light on the lasting imprint of China’s past encounters with the Islamic world as well as an exploration of the increasingly vibrant and complex dynamics of contemporary Sino-Middle Eastern relations. Read more ...

Convergence is the exception that proves the rule. While Japan converged into the Western economic institutional system to orchestrate its outward direct investment in the Asia-Pacific, China has made clear that it will not conform to the Flying Geese Paradigm of East Asian Development. China’s domestic industrial de-structuring is now passing through the same phase as Japan’s, coordinated through Supply-side Reform policy. Yet China’s external trade and industry policy is centered on the Indian Ocean, not the Pacific. And the industrial transfer policy is to maintain a Chinese governance model on a closed value chain — in effect creating a parallel trade and industry regime.

International Capacity Cooperation is the policy that coordinates China’s domestic finance, industry and trade institutions into a holistic Belt and Road “going out” industrial transfer strategy. It would be incorrect to analyze China’s foreign direct investment in these geographic areas at the firm level. Industrial transfer funds, administrative government unit matchmaking, and external industrial associations have all been developed to facilitate the institutionalization of the industrial transfer trade policy to the Middle East.

China’s non convergence with the post Bretton-Woods trading system means its domestic institutions will shape the global economy as well as regional economic orders in the Middle East, Central Asia, East Africa, and North Africa. In the Middle East and Central Asia, the form of China’s external industrial policy is becoming clearer through formation of specialized domestic China institutions in both finance and industry. In the Middle East, this geo-industrial policy centers on energy equipment manufacturing, satellite technologies, and both traditional and new energy.

Offshoring China’s Project-System to the Middle East

There are clear institutional interrelationalities between China’s domestic public finance architecture, central government ministries, local government industrial clusters, and industrial enterprises. However, for China, the missing institutional element from this industrial policy transmission and coordination chain is convergence with the host economy. International Capacity Cooperation is China’s policy answer to coordinating industrial clusters in sovereign states. It is the practical industrial policy matrix through which industries, local governments, and policy banking are designed to intersect with partner economies as part of the wider geo-economic Belt and Road strategy.[1] It is also effectively a circumvention of comparative advantage.[2]

China’s industrial investment policy narrative for the Greater Middle East was laid out in a 2016 Middle East White Paper, and is focused on exporting industrial capacity in civil nuclear, traditional and new energy and space satellite cooperation. While Central Asia is slated for soaking up China’s excess heavy industries in steel, nonferrous metals, cement, and glass, Beijing is bringing stand-alone industrial clusters to the Middle East in advanced production industries such as energy and energy equipment, communications, construction machinery and equipment, aerospace, transport, marine and marine engineering.[3]

The whole Middle East geography is a strategic geo-satellite location for China; the 2016 Middle East white paper targeted space communications and traditional mobile telecommunications infrastructure.[4] The policy paper identified agro-industrial and aquaculture industries as secondary industrial sectors, calling for both industrial transfer and industrial scientific development capacity, particularly rain-fed agriculture and veterinary sciences.[5] While popular narratives have centered on China’s investment in traditional construction in port and trade logistics infrastructure, the wider macro-strategy is the use of this infrastructure as part of transitioning China from an export-led economy to a net importer.[6] This means a focus on feeding China, moving low-end manufacturing centers abroad for re-import to Chinese consumers, and building Indian Ocean-centric regional production networks for investment in next-generation technology and industry.

Industrial Integration in Saudi Arabia, Iran, Egypt, Oman, and UAE

China’s investment in Middle East industry and technology will be strongly drawn to projects that sit within its overall design for an Indian Ocean geo-industrial policy. China’s investment in strategic Middle East economies is not simply a matter of Belt and Road infrastructure building. Even where infrastructure is being built, such as in Oman and in Afghanistan, the end result is an import trade strategy, to use the built infrastructure as part of a new trade paradigm. Investment in strategic ports and trade lines can be likened to stock and flow investments. Think of China’s capital building a port as stock, but the major investment is in controlling the flow of trade through the port.

In Saudi Arabia and Iran, China is expecting to invest in civilian nuclear energy equipment manufacturing plants. China itself is looking to replace energy dependence on Russia with a traditional Middle East energy plan. Oil exploration, production, transport and refining, as well as oilfield engineering services and equipment trade, are all on the agenda for China. China also plans to strengthen investment in solar, wind, hydropower and other renewable energy. China’s firm-level investments are also changing the face of energy production within the Middle East (e.g., State Grid’s rollout of China’s EHV transmission technology in Egypt’s 500 kV backbone network upgrade project).[7] In a rare display of two-way investment, Saudi Arabian American Oil Company (Saudi Aramco) is expected to sign an agreement with PetroChina to invest in an oil refinery in Yunnan province, and China’s national defense giant China North Industries Group (NORINCO) and Aramco have signed a framework agreement to establish a refinery complex in northeast China.[8][9]

Overwhelmingly clear is China’s secondary capacity transfer plans in agribusiness. Agriculture and aquaculture exports from Oman, Iran, and Afghanistan are designed to orchestrate a structural shift to China’s Xinjiang province as a net food importer, helping China to build trade and logistics complementarities along Myrdalian economic theory. The Middle East agrifood production network will also serve as a logistics hub for China’s wider agrifood exports from investments in East Africa. The Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences Institute of Coconut plans to establish a ‘China-Emirates Date Palm Agricultural Technology Park’ in Dubai, and a sugar refinery in Oman built with Chinese capital in the port of Sohar.[10] [11] And Iran recently approved a ‘Science Foundation for the Silk Road’ in Tehran to invest in nanotechnology, renewable energy, brain cognitive science, and biotechnology.[12] Food technology and food safety also feature prominently in China’s wider trade and investment plans.[13] [14] In terms of spatial industrial policies, China is billing Hainan as the Dubai of the East or the new Hong Kong, to be funded by the China Ocean Strategic Industry Investment Fund, which was established in 2016.[15]

Match-making Provinces to Sovereign States

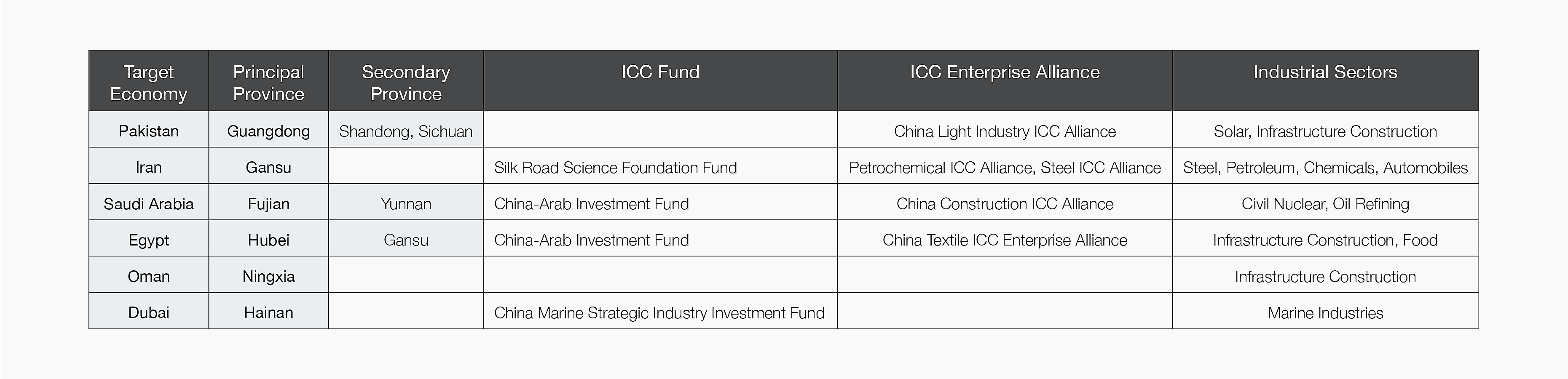

The most important aspect of China’s industrial transfer policy in the Middle East is the matching of sovereign states with Chinese provincial and prefectural administrative units in order to coordinate liquid and fixed capital transfer to external geographies. This mechanism means that domestic Chinese institutions will trump international institutions in the new trade paradigm. These intergovernmental pairings link the state investment funds and the state offshore industrial associations, mating local government administrative units with external economies. They are similar to sister city relationships but are more practical and designed to foster tangible investment and industrial transfer.

Through 2018, China’s policy for matching provinces and prefectural cities to sovereign states is becoming clearer; for example, pairing Hebei province with Kazakhstan, Gansu province with Iran, Fujian province with Saudi Arabia, Hubei province with Egypt, Ningxia province with Oman, and Hainan province with Dubai. One of the earliest ICC matchmaking connections was between the National Development and Reform Commission and the Hubei Provincial Government to establish an institutional mechanism for taking the Hebei equipment manufacturing industry to Kazakhstan.[16] Hubei was directed to create supportive policies to facilitate the “going out” of iron and steel, cement, plate glass, automotive parts, optoelectronics, photovoltaic cells, agricultural commodity processing, and energy equipment in Central Asia, the Middle East, East Africa, and Eastern Europe.[17] This pattern will repeat as the institutional matchmaking develops in China-Middle East industrial transfers.

Figure 1. China’s Middle East Industrial Policy Docking Institutional Matrix

Subnational administrative units in China are also matched with subnational units in host economies, such as Luoyang in Henan province with Bukhara in Uzbekistan or Iran’s Qom province matched with China’s Gansu province. [18] However, for the most part, China’s external trade and industry policy is spatially planned for matchmaking economies of similar size, geographic proximity, or industrial complementarity. So expect many more provincial-level to sovereign state administrative matchmakings to take place in the coming 2018-2020 period.

Institutional interrelationships between the multiple levels of government and industry coordination are only beginning to emerge. But a clear pattern is forming of a governance chain replacing the value-chain. As Maritime Silk Road funding comes down the government line from the policy banks, we will see ever clearer fixed capital investment plans for entire industrial complexes on ocean-frontage economies in the Middle East, particularly for Oman, Iran, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia.[19] We can also expect to see production of food, energy equipment, energy, and heavy industry commodities in Iran, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Oman to be completely within China’s industrial finance external governance. This fundamentally reshapes the global trade and investment paradigm and recreates a closed value chain model in China’s external geographies.

Industrial International Capacity Cooperation Enterprise Alliances

China state industrial policy in the Middle East is essentially employing vertical integration. David Kelly recently reminded us all that there is no such thing as private capital in China. There is only state and less-state, and any “private” enterprise is dependent on state-owned banking capital.[20] The state-owned enterprises are coordinated by industrial sector under an International Capacity Cooperation Enterprise Alliance. These are mirrors of the industry associations that govern China’s domestic industries. There are remnants of the ministerial-coordinated complete vertical integration under the planned economy.

For example, China’s domestic aluminum industry association is simply the last institutional remains of the Ministry of Non-Ferrous Metals. These industry associations are now vice-ministerially governed units that are often in charge of China’s commodities import policies and price setting. In 2017, China established a China Non-Ferrous Metals Industry International Capacity Cooperation Enterprise Alliance to facilitate state aluminum production in external economies. It is clear now that these institutions exist for all industrial sectors (e.g., the China Construction Industry International Capacity Cooperation Enterprise Alliance, and the China Iron and Steel Industry International Capacity Cooperation Enterprise Alliance).

These International Capacity Cooperation enterprise alliances are then matched to regional specific policy bank funds, such as the China-Arab Investment Fund, the China-Kazakhstan Industrial Development Fund or the China Marine Strategic Industry Fund. Each fund has its own regional and industrial sector strategic investment goals. These play on three factors: 1) China’s regional industrial restructuring needs; 2) industrial complementarities in the host region; and 3) macro national strategies. This means a typical International Capacity Cooperation industrial transfer project would fund a local Chinese industrial complex to close, to relocate outside the country, and then to use the outputs of that external facility to serve state geo-economic goals.

This means China’s industrial investment strategy in Middle East host economies is orchestrated by the equivalent of a China ministerial bureau for foreign steel production, leveraged on policy bank investment, with enterprises centrally coordinated to fulfil state industrial policy goals. Imagine the Singapore or Hong Kong industrial development model, but with China Communist Party control. While the strategy is effectively creating a bubble version of China’s economy in Middle Eastern economies, it is not so much a sophisticated grand strategy, but rather a means of perpetuating its domestic industrial planning and financing system abroad, instead of undergoing a difficult institutional change at home.

Conclusion

While geo-policy hawks race to the military-security nexus, and the free-trade crowd of the Pacific stress firm-level outward direct investment analyses, there is little space for political economy analyses that see China’s Indian Ocean trade strategy in economic terms, but not neoclassical terms. Yet not all state-capital analyses need rush to debt-trap scenarios and militarization narratives. There is a place for China’s state capital in the Middle East. It is rational for China to feel its capital institutions subservient to the international orthodoxy. It is equally rational for states such as Iran, ostracized by the US under globalization 1.0, to seek new trade and investment partners.

But China’s globalization 2.0 comes with serious risks. Without a freely exchangeable currency and with the hangover of local government debt in its banking system, Chinese capital itself carries inherent risks that European, American, and Japanese capital does not. This is not simply a case of China taking its place in the global investment architecture; it is a rewriting of the global trade and investment institutional norms. A closed model of production in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, or Iran under China’s domestic governance model is effectively a parallel trade policy. It is a state-capitalist industrial policy pursued in an external geography, and one that does not touch the conventional balance of payments and international exchange state accounting regime.

While this capital may be branded variously as private equity investment, private enterprise investment, state aid, or multilateral international assistance loans, the macro strategy is clearly centered on a vertical integration of China’s industrial production in external geographies. By expanding this alternative to the default global trade, industry and investment regime, China’s parallel trade policy is an advanced form of financial neo-mercantilism that will, by definition, run adjacent to existing WTO trade rules, and will ultimately challenge their existence.

[1] National Development and Reform Commission, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Ministry of Commerce jointly issued the “Vision and Action for Promoting the Joint Construction of the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road,” Xinhua, March 28, 2015, accessed May 1, 2018, http://www.xinhuanet.com/fortune/2015-03/29/c_127633221.htm.

[2] PRC State Council, “Guiding Opinions on Promoting International Capacity Cooperation and Equipment Manufacturing,” May 16, 2016, accessed May 1, 2018, http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2015-05/16/content_9771.htm.

[3] “International Capacity Cooperation 13th Five-year Plan Development,” Economic Information Daily, appearing in Xinhua, October 26, 2016, accessed May 14, 2017, http://jjckb.xinhuanet.com/2016-10/26/c_135782137.htm.

[4] Tristan Kenderdine, “Coordinating China’s Satellite Constellations,” Policy Forum, July 20, 2017, accessed May 1, 2018, https://www.policyforum.net/coordinating-chinas-satellite-constellation….

[5] PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “China’s Policy Paper on Arab Countries (full text)” Xinhua, January 13, 2016, accessed May 1, 2018, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2016-01/13/c_135006619.htm.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Wang Yunsong, “Capacity Cooperation Benefits Egypt’s Economic Development (China is Economic ‘Stabilizer’),” People’s Daily, August 27, 2016, accessed May 1, 2018, http://world.people.com.cn/n1/2016/0827/c1002-28669845.html.

[8] Tao Yujie, “Saudi Arabia Plans to Complete Investment in Yunnan Refinery within Six Months,” Wall Street CN, August 24, 2017, accessed May 1, 2018, https://finance.qq.com/a/20170824/006018.htm.

[9] Ibid.

[10] China PRC Ministry of Science and Technology, “Secretary of the Dubai Land Department of the United Arab Emirates to Discuss Technology Cooperation with Hainan Province,” August 28, 2015, accessed May 1, 2018, http://www.most.gov.cn/dfkj/hain/zxdt/201508/t20150827_121387.htm

[11] China PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Ambassador to Oman Yu Fulong Attends Signing Ceremony of Oman Refinery Sugar Project,” Embassy of Oman, June 8, 2015, accessed May 1, 2018, http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/gjhdq_676201/gj_676203/yz_676205/1206_67625….

[12] Ding Jia, “Chinese Academy of Sciences Signs Silk Road Science Fund with Iran,” Sciencenet, January 28, 2016, accessed May 1, 2018, http://news.sciencenet.cn/htmlnews/2016/1/337368.shtm.

[13] He Yingyi, “Gansu Business Institute to Carry out Technical Cooperation with Iran,” China Economic Weekly, accessed May 1, 2018, http://www.ceweekly.cn/2017/0117/178339.shtml.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Jia Kang, “China Marine Strategic Industry Investment Fund Established in Hong Kong,” Silk Road News, accessed May 1, 2018, http://silkroad.news.cn/invest/6912.shtml.

[16] National Development and Reform Commission, National Development and Reform Commission and the Hubei Provincial Government Establish a Mechanism to Promote the Coordination of the International Capacity Cooperation Committee, December 14, 2015, accessed May 1, 2018, http://www.ndrc.gov.cn/gzdt/201512/t20151214_762287.html.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Gansu Provincial Overseas Affairs Office, “Matchmaking Conference on the Economic and Trade Cooperation between Iran’s Qom Province and Gansu Province Held,” July 9, 2016, accessed May 1, 2018, http://www.gsfao.gov.cn/news/chuggl/2016/79/DGBJ.html.

[19] Sun Tianyuan, “What is International Production Capacity Cooperation?” State Council of the People’s Republic of China, December 24, 2015, accessed May 1, 2018, http://english.gov.cn/news/video/2015/12/24/content_281475259847295.htm.

[20] David Kelly, “Reining in ‘Red Entrepreneurs,’” East Asia Forum, January 26, 2018, accessed May 1, 2018, http://www.eastasiaforum.org/2018/01/26/reining-in-red-entrepreneurs/.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.