Last updated on November 24, 2025

Introduction

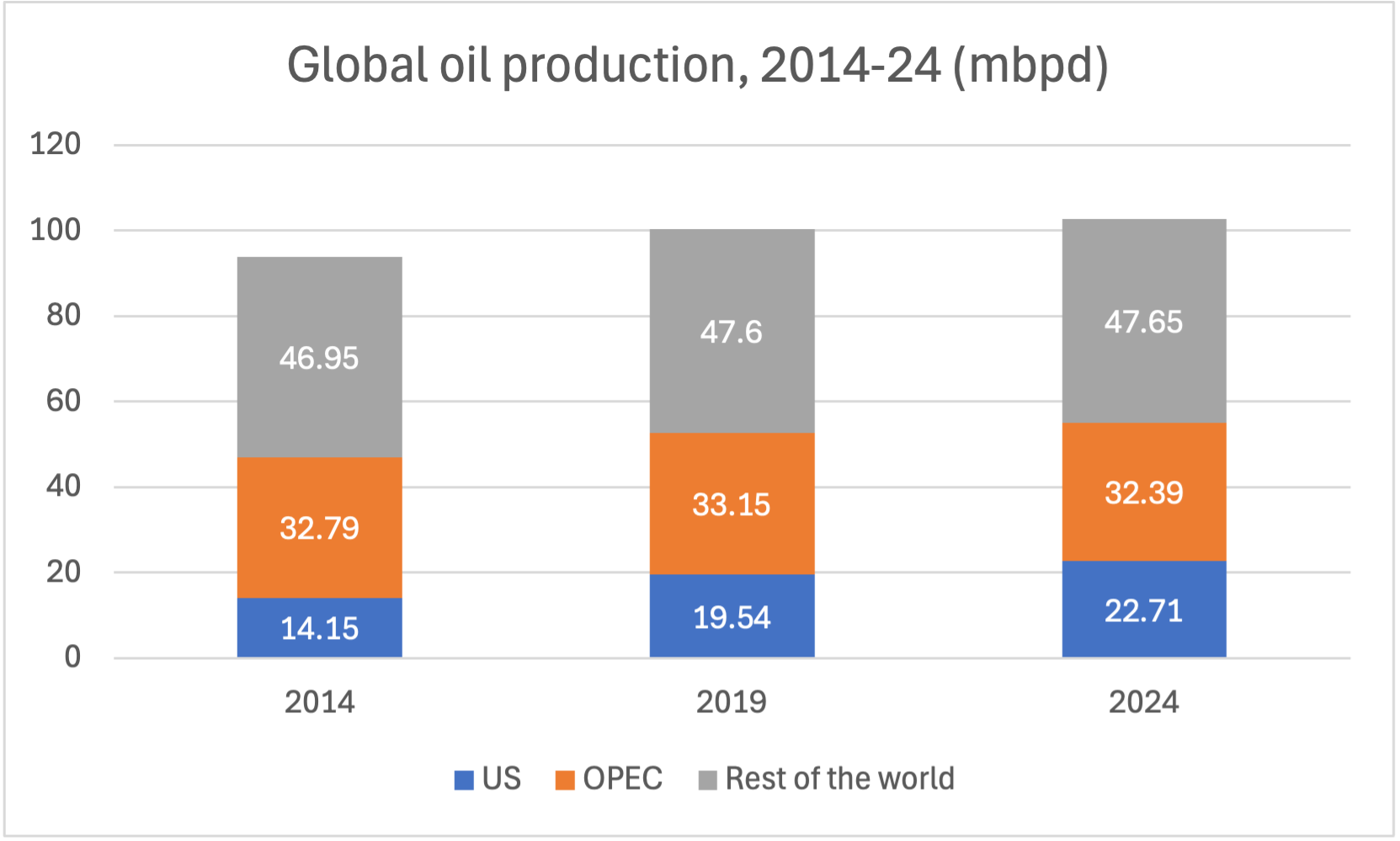

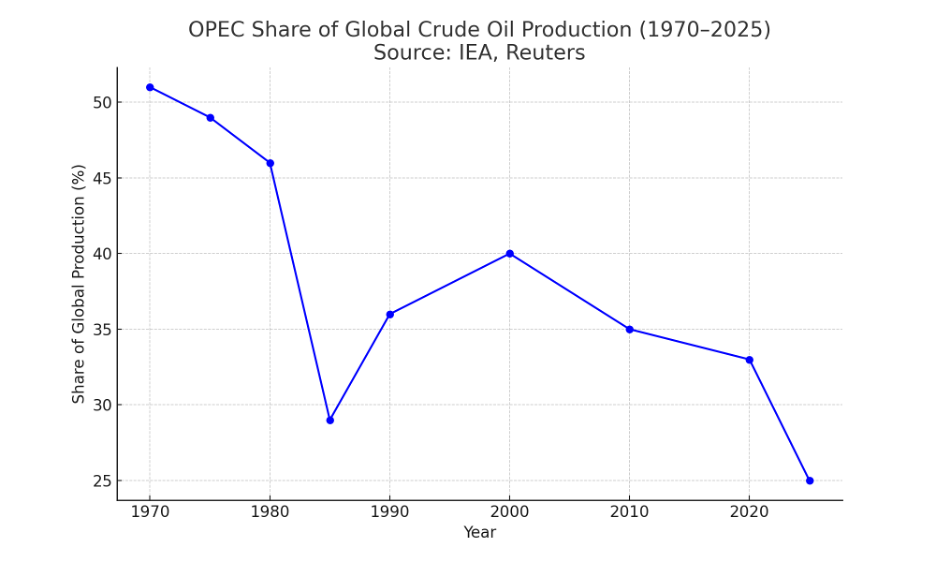

A key player in the oil industry and central to producer-consumer relations, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) was formed by major oil exporters to stabilize prices and sustain development among its member states. It pursues its goal of price stability through the use of quotas, which are agreed upon by the bloc and set a total level of production. Currently, OPEC has 12 members, including Algeria, the Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Venezuela, which together control around 30% of the global oil supply. Since 2016, OPEC has cooperated with a group of non-OPEC oil-producing countries through the OPEC+ framework, which also includes Russia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Bahrain, Brunei, Malaysia, Mexico, Oman, South Sudan, and Sudan, bringing its total output to about 41% of global production.

While the organization has changed over the decades, its core goal remains the same: to balance oil supply with demand in a manner that defends prices and ensures revenues do not fall significantly. Over the past several years, this mission has become more difficult to maintain, as ongoing issues, like the green energy transition, quota non-compliance or at times underproduction, and departures from the bloc, have begun to cast doubts on its efficacy and longer-term prospects.

OPEC’s Structure and Function

Headquartered in Vienna, Austria, OPEC is composed of a three-body structure divided into the Secretariat, the Conference, and the Board of Governors. The Secretariat, controlled by the secretary-general, is chosen by the Conference and enacts the policy generated by the other two bodies over their three-year terms. The Conference is the main deliberative body, and each country sends delegates who are apportioned a single vote on bureaucratic matters and overall policy. Finally, the Board of Governors consists of members appointed to two-year terms who then devise the organization’s yearly budget.

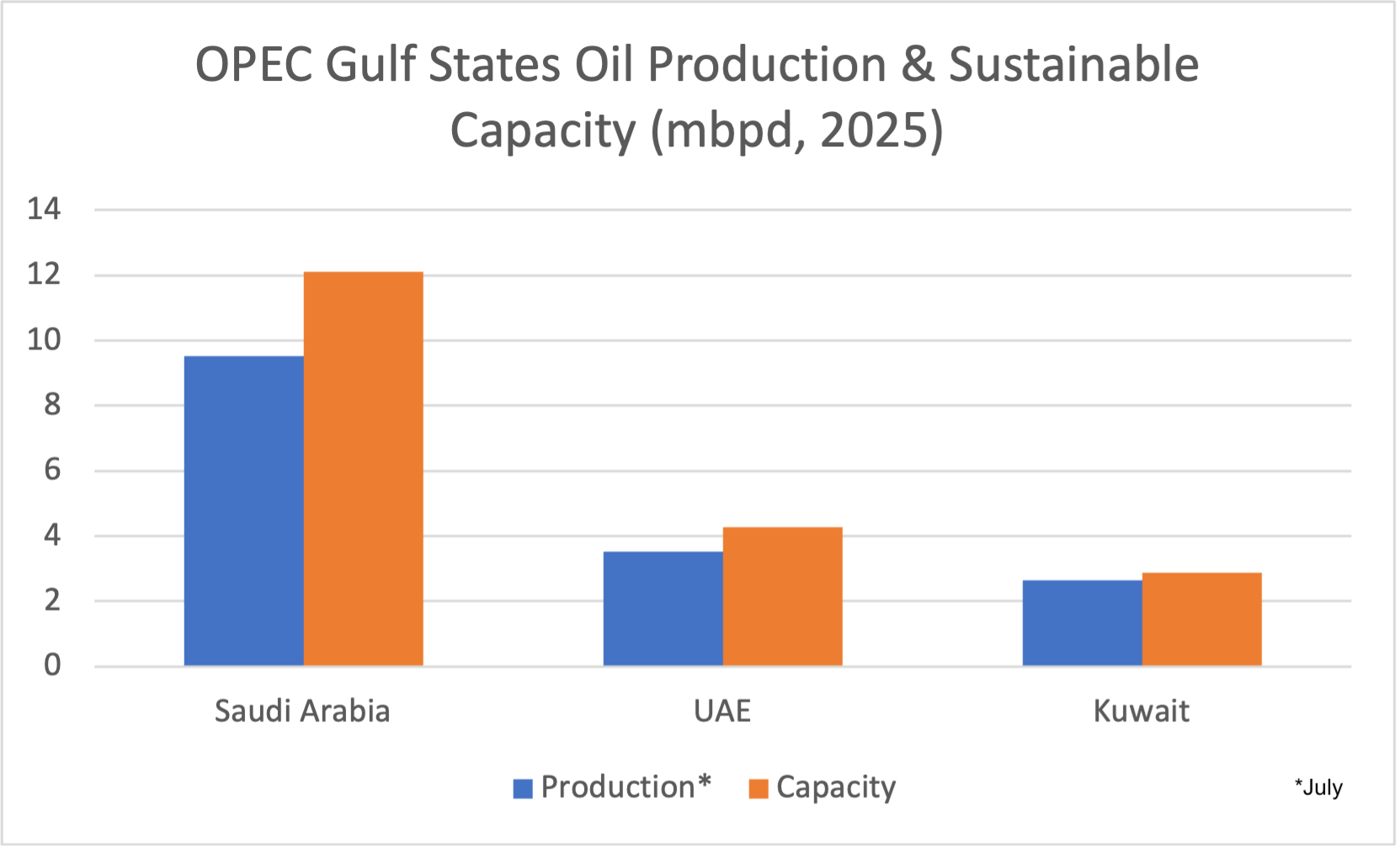

OPEC’s primary functions are conducted at meetings held throughout the year. At Joint Technical Committee (JTC) meetings, technical experts discuss the overall condition of the oil market and make recommendations to the ministers based on their findings. Joint Ministerial Monitoring Committee (JMMC) meetings are held bi-monthly to consider the JTC’s recommendations and monitor compliance with quotas. Most important are Ministerial Meetings or Conferences, which take place every six months (or on an extraordinary basis) and where policies on quotas, target prices, future meetings, and other matters are decided. While the secretary-general is OPEC’s official leader and the various meetings of ministers and technical experts appear to guide policy, Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf countries wield considerable influence due to their political stability and large sustainable output capacity — roughly 19 million barrels per day (bpd) as of July 2025, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), or nearly 60% of OPEC’s total. Thus, the Gulf often directs the tone and focus of strategy discussions.

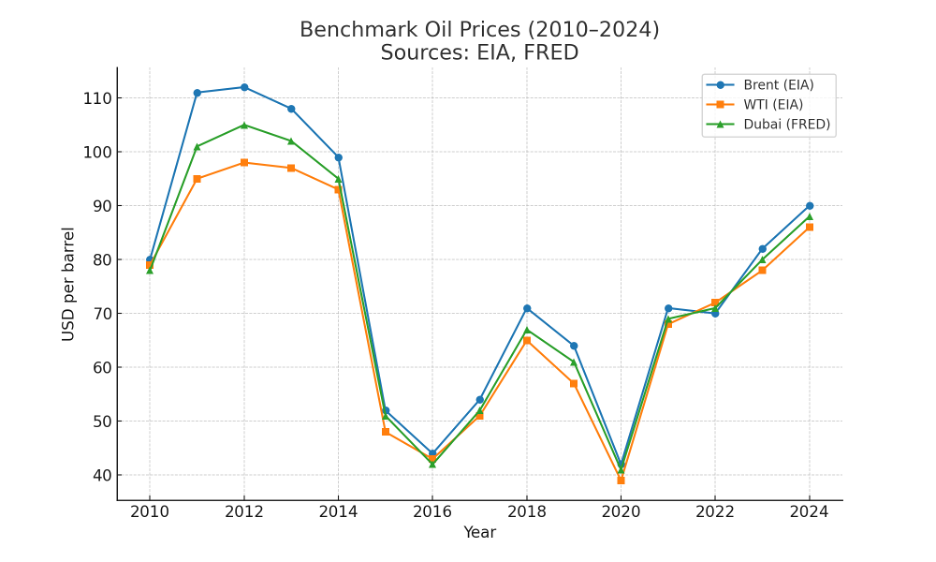

OPEC and OPEC+ focus on influencing oil prices and market share through various means. Oil prices are determined by the interaction of supply and demand in the broader market. Traders use so-called benchmark prices, which represent the selling price of oil mixes like Brent, Dubai/Oman, and West Texas Intermediate (WTI), as a shorthand for these abstract processes, and sell the various grades of oil at a premium or discount based upon them. OPEC influences these prices by making use of its large share of crude production to increase or decrease the available supply of oil in the market. This influence over supply is composed of its decisions on quotas, the actual amount its members produce, and its available spare capacity. For example, in response to falling prices in 2018, OPEC opted to maintain existing production caps, which eventually helped drive prices beyond $80 per barrel.

The bloc’s actions in recent years have been mixed, as it has pursued either defense of key price bands or an alternative market share strategy depending on market fundamentals. In 2021, OPEC+ opted to increase production quotas by a monthly 400,000 bpd in an attempt to maintain and expand its market share as a result of both political concerns and forecasts indicating a smaller oil surplus in 2022. By pursuing a market share strategy, OPEC+ can discourage the development of non-OPEC+ oil supplies while maintaining its share of production.

OPEC’s Establishment and Early Years

In 1960, five major oil-producing states — Iran, Iraq, Venezuela, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait — met in Baghdad to found OPEC, which became the official venue where producers could work to coordinate oil production and maintain prices. Another original component of OPEC’s purpose was to oppose the market dominance of Western oil firms, which would also foster a move toward state-driven oil policy.

The bloc’s early years were marked by difficulties with coordination; however, the subsequent decade would see OPEC emerge as a preeminent actor in the market. By the 1970s, global oil demand began to outpace supply — driven in part by “peak oil” in the US and the decline of American oil exports — thus strengthening OPEC’s position. In 1973, in response to the Arab-Israeli War, OPEC capitalized upon both an increase in nationalism as well as bargaining power to coordinate direct market intervention as a bloc by reducing oil production. In November of that year, OPEC cut production by 4 million bpd, and the price of oil increased from $3.29/barrel (bbl) to $11.58/bbl.

New Challenges in a Changing Market

OPEC now finds itself in a wholly new position, as countries rely upon a far more diverse mix of energy types and sources of supply that are no longer as concentrated under OPEC member states. In response, OPEC has had to redefine itself somewhat. The bloc has stated that its current mission is simply to coordinate policy and stabilize oil markets. However, many economists continue to view OPEC as a cartel whose members’ central goal is to extract rents in excess of the market equilibrium by reducing competition between themselves. While the original members of the organization were located mostly in the Middle East, it now features increasing membership from Africa.

There has been some volatility in the bloc’s membership in recent years, with Indonesia leaving in 2016, Qatar in 2019, Ecuador in 2020, and Angola most recently in 2024. Gabon left in 1995 but rejoined in 2016; before Ecuador left in 2020, it had exited in 1992 and rejoined in 2007. These departures have taken place for a variety of reasons, but disagreements over output quotas are the most commonly recurring theme. Countries like Angola and Ecuador complained that the quotas hindered their ability to attract investment and extract oil rents and, having failed to come to an acceptable compromise, exited the bloc.

The shale boom, which permitted profitable extraction from previously unattainable fields, ushered in a particular sea-change in OPEC’s modern history. Thanks to the development of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) technology, US oil production, which had experienced a decline following the 1970s, rose dramatically in the 2000s, from just 6.8 million bpd in 2007 to 13.1 million bpd by 2017, turning the US back into a net oil exporter. This glut of supply eventually led to global oil prices falling from $100 to just $50 by 2015, and inducing major changes in OPEC’s strategy.

“OPEC now finds itself in a wholly new position, as countries rely upon a far more diverse mix of energy types and sources of supply.”

The Rise of OPEC+

Responding to these unfavorable conditions, in 2016 the bloc signed an agreement with 10 other oil-producing countries to form OPEC+. By bringing together a larger collective of producers, and thus a greater share of global supply, OPEC+ would theoretically bolster its ability to balance the market by coordinating production cuts. OPEC+ has been a moderate success for the bloc, and during 2017-20 it was able to keep prices around 6% higher than they might have been otherwise. The organization’s main focus in recent years has been to stabilize declining prices in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, when lockdowns and reduced travel resulted in an unprecedented collapse in demand.

More recently, however, OPEC+, led primarily by Saudi Arabia, has been increasing supply. During 2025, a number of revisions raised the bloc’s quota by a total of 2.9 million bpd. This change in strategy is an attempt to place downward pressure on prices to regain market share, reinforced by diplomatic overtures from US President Donald Trump. In early November, the organization agreed to a small increase in production for December and a pause in increases for the first quarter of 2026.

US Government’s Approach Toward OPEC

US-OPEC relations have fluctuated between periods of diplomacy and rivalry due to geopolitical events and shifting dynamics as the US has sought to reduce its dependency on oil imports. The first Trump administration was initially critical of OPEC, condemning it for price manipulation. However, faced with reduced oil demand in the midst of the pandemic in early 2020, it shifted its rhetoric from condemning OPEC to encouraging coordinated action on behalf of OPEC+. The Russia-Ukraine war has strained US-OPEC relations since 2022. US policymakers widely condemned OPEC+’s decision to cut oil production by 2 million bpd in October 2022 for indirectly benefitting Russia — this counterbalanced the impact of restrictions placed by the European Union and Group of 7 (G7 — Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the US) on Russia’s oil sales. Such geopolitical tensions influenced President Joe Biden’s administration to increase its focus on boosting domestic energy production to reduce OPEC's control over global prices.

Various US administrations have sought to pressure OPEC — particularly by leveraging the strategic US-Saudi relationship — to adjust its production quotas to meet US import demand. In April 2020, the Trump administration levied its strategic relationship with Saudi Arabia to press the kingdom to reduce OPEC’s production — brokering a cut of 9.7 million bpd — to end its price war with Russia. The Biden administration also threatened “consequences” for US-Saudi relations following the announcement that OPEC+ would cut its oil production target over US objections in October 2022, although the administration ultimately backtracked on these threats. During the second Trump administration, oil producers have responded to the president’s decision to impose tariffs on OPEC+ members in April 2025 by increasing supply to win back market share and offset declines in revenue associated with lower production while prices are low.

Congress has sought to reduce the influence of OPEC/OPEC+ over global oil markets. In July 2024, Congresswoman Nanette Barragán (CA-44) and Senator Ed Markey (MA) introduced the Big Oil Collusion Accountability Act, which aims to hold fossil fuel companies accountable for colluding with OPEC to raise prices. Concerns regarding inflation following the OPEC+ production cut in 2022 spurred renewed bipartisan action surrounding the No Oil Producing and Exporting Cartels Act (NOPEC) — which would subject OPEC national oil companies to US antitrust lawsuits. The most recent iteration of NOPEC was introduced by a bipartisan group of senators in March 2023. However, lobbying by oil corporations and concerns over geopolitical retaliation have consistently stalled NOPEC from passing into law over the last two decades. Recent efforts by lawmakers have instead focused on legislation to buttress US energy independence, including with tax incentives for US oil producers included in the “One Big Beautiful Bill” that President Trump signed into law on July 4, 2025.

Importance and Implications

OPEC/OPEC+ is of particularly critical importance to petroleum producers whose economic development and political stability rely on dependable, elevated oil revenues. For Saudi Arabia, oil accounted for 62% of government revenue in 2024, with a relatively high price of $90 per barrel needed to balance its budget. Coordination enables members to defend price stability and thus allows for robust planning for the future. For major consumers like the United States, on the other hand, OPEC has the capacity to significantly reduce the quality of life of their citizens through increased energy costs and broader inflation. Geopolitically, OPEC can shape the formation and evolution of consumer-producer relationships, and it also has the capacity to promote the foreign policy strategies of its member states. A final aspect of OPEC’s importance is the perceived prestige associated with being a member. Member states are able to signal both their importance on the international stage abroad as well as their commitment to protecting their national interests domestically.

Questions abound, however, about the degree of actual economic control the organization exerts over the oil market today. Some scholars posit that the bloc’s value is not as a market-controlling cartel, but rather as a political organization. Efforts to target prices are limited by generous quotas and cheating, the challenges of reducing or increasing production in the short term (OPEC produced at 91.3% of existing capacity on average from 2003 to 2022), and lack of a clear relationship between OPEC’s actions and resulting prices. Adding to skepticism about OPEC’s utility is the fact that quotas have frequently been a point of tension within the bloc, as not all members believe that the unique circumstances faced by producers are taken into account. Libya, Iran, and Venezuela are also exempt from quotas, thus increasing the difficulties associated with supply-side market management. In sum, while the bloc may have power to influence prices in the short term, the perception of its long-term control over the oil market could well be exaggerated.

Demand Outlook and Long-Term Sustainability

Despite OPEC’s predictions that oil demand will remain robust in line with a 24% increase in overall energy demand by 2050, others, such as the IEA, disagree. Since 2023, global oil demand has seen only modest growth; it is expected to slow throughout 2024-30 and even decline toward the end of the period. The IEA attributes much of this to reduced demand from Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries and China, driven by the large-scale buildout of renewable energy capacity and electrification of transportation. Regardless of the exact timeline, a potential decline in demand represents a problem for OPEC+ members, as their economic development is tied to oil revenues. While some OPEC+ countries, like Saudi Arabia, have attempted to diversify their economies, oil still comprises a significant portion of their exports and yearly budgets. As of 2024, Riyadh had reduced oil as a share of exports to roughly 73%, down from 93% in 1991. In addition, abstract fears about peak oil have induced some members to adopt a “use it or lose it” approach to production, exceeding their quotas amid concerns that hydrocarbon reserves could become stranded assets. This problem is compounded by OPEC’s lack of a formal mechanism for sanctioning countries that regularly overproduce, like the UAE. Quota evasion degrades both the bloc’s overall ability to maintain stable markets as well as the market’s confidence in its stated quotas. If members continue to flout the quota, or even depart the organization, as Angola did in 2024, OPEC’s influence over markets could potentially wane, putting the long-term sustainability of the organization at risk.

This backgrounder was researched and written by MEI summer 2025 intern Joseph Hoess, with input from Senior Fellow Colby Connelly.

Top photo by Simon Dawson/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Access Additional MEI Expertise

The Middle East Institute has a number of renowned experts who are well versed on the topic of OPEC/OPEC+, including MEI Senior Fellow Colby Connelly, Senior Fellow Karen E. Young, Associate Fellow Nikolay Kozhanov, and Associate Fellow Li-Chen Sim. Our experts are available for interviews or commentary. For assistance with reaching Mr. Connelly or any of our scholars, please send an email to media@mei.edu or call 202-785-1141 ext. 241.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.