The annual Conference of the Parties (COP) was initiated by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1995 to assess progress made by UN members in dealing with climate change. Some meetings have had practical and measurable outcomes, such as the Kyoto Protocol of 1997. But arguably the most well-known meeting is the 2015 COP21 in Paris, also known as the Paris Agreement.

COP21, having been more heavily advertised than its predecessors, built-up high level of expectation regarding a relatively straightforward aim – to reach global consensus on a binding agreement for the mitigation of climate change. And it formally did reach one, by setting a goal to limit global warming to “well below 2 degrees Celsius” compared to preindustrial levels, while pursuing efforts to stay even within the 1.5 degrees Celsius threshold.

While the agreement was unanimously signed by the 196 state parties, some countries delayed ratification. Among them were Iran and Turkey, the latter of which became the only G20 member not to endorse the Paris Agreement despite 24 Turkish cities and municipalities committing themselves to the Agreement and urging central authorities to do the same. The United States subsequently announced its intention to withdraw from the Agreement, a complicated and laborious process which will depend on the 2020 election outcome.

In 2015, COP21 was seen as a tremendous diplomatic achievement for two main reasons. Apart from the obvious climate change objectives – rebuilding the foundation, at least on paper, for ambitious targets of decarbonizing global economies – COP21 established a truly universal agreement. This was a joint effort to steer countries’ ambitions towards more sustainable energy, transportation and agriculture sectors, and to develop specific medium- and long-term action plans. But has this transpired?

It’s difficult to assess whether or not the Paris Agreement played a significant role in some climate-associated targets, be they determined at the union levels (i.e. EU) or self-established national ambitions. What is clear though is that, as several independent sources have analyzed, progress made in the past five years is not nearly enough to reach the overall target of limiting global warming to “well below 2 degrees Celsius”.

As the COVID19 crisis has clearly showed, the idea of a “global effort” is aspirational at most. First, the pandemic response has been treated as a national responsibility, not a regional or international one. In addition, the current vaccine race also tends to focus on each nation’s hedging strategy to acquire the serum, rather than international coordination and prioritization. Wearing masks has also proven a challenging measure to be implemented, even at the sub-regional level, despite individual efforts. With the impact of COVID19 immediately visible and urgent, the climate change challenge may now not seem such a priority. Global consensus and targeted measures seems, now more than ever, a rather utopic desiderate. Moreover, the need for a “V-shape” economic restart can also prove detrimental to regional or global common actions, at least in the short run, as countries will need to focus on national recovery plans. Hope is still intact though, as individual measures – as in the case of social distancing and mask-wearing – can play an important role in advocating for climate change efforts.

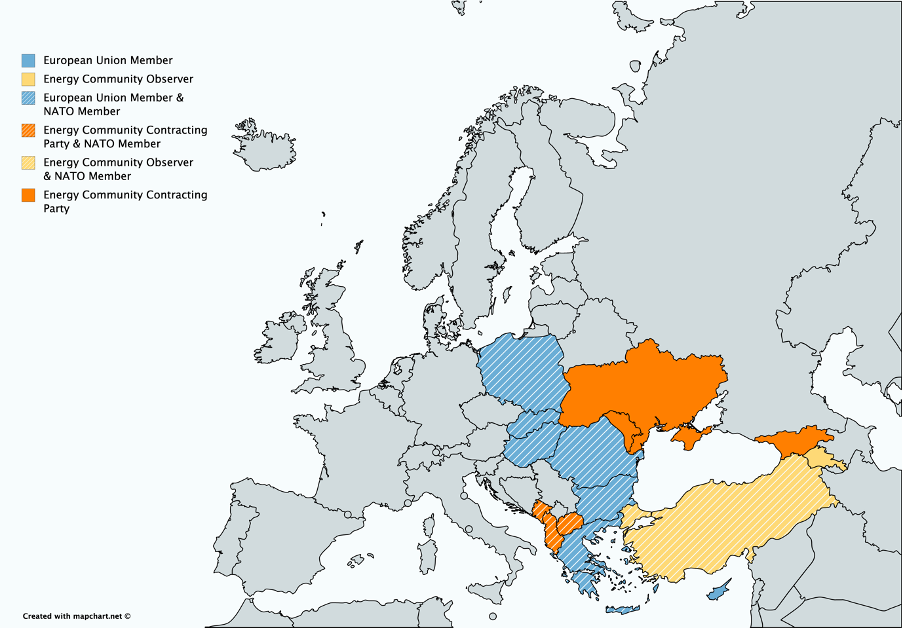

Beyond the general difficulties associated with international cooperation, regional characteristics such as historical geopolitical tensions, societal challenges or migration issues, add a further layer of complexity. This is the case with the Black Sea region. As previously analyzed, the Black Sea region is a complex geographical area at geopolitical and economic crossroads. Neighboring states are part of different general administrative unions or alliances, making it a unique case study for analysis.

This is particularly visible when looking at the areas of energy and climate given the combination of different affiliations, each calling for different targets, some binding and others not.

For its member states Turkey, Romania, and Bulgaria, NATO affiliation is synonymous with energy security and energy independency. On the other hand, EU membership (in this case for Romania and Bulgaria) calls for specific 2030 binding targets for renewable generation and provides a functional emission trading system. At the same time, Energy Community – an international organization established between the EU and a number of third countries to extend the EU internal energy market – commits in theory to implementing the relevant EU energy acquis communautaire, to developing an adequate regulatory framework, and to liberalizing their energy markets in line with the acquis under the Treaty.

In this context, climate change related issues translate into a difficult and continuously changing equation. Preexistent societal, economic and geopolitical challenges - the “what” of the formula - call for different approaches from neighboring countries - the “who”. Based on Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports and judging by warnings from the scientific community, the “when” should be defined as no later than 2030 if the agreed figures are to be reached by 2050. While the “why” is clearly represented by pressing climate change issues and global warming, the “how” remains the greatest unknown variable.

Keeping the mathematical correspondence, the situation perfectly fits the definition of a “differential equation”, as it relates to more functions and derivatives and the associated research consists in the study of its solutions’ proprieties and effects.

Andrei Covatariu is a Fellow for MEI's Frontier Europe Initiative. He is a Senior Research Associate and the Summer School Director at Energy Policy Group. The views expressed here are his own.

Photo by Vyacheslav Argenberg

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.