Summary

The Middle East is undergoing a historic transformation with unprecedented opportunities to build new relationships, de-escalate tensions, and foster conditions for stronger integration. At the same time, the region remains on edge because of ongoing tensions in Yemen, Syria, Iraq, and other conflict zones, a civil war that broke out recently in Sudan, along with the overarching challenges presented by fraught relations between Iran, Israel, and several Arab Gulf countries — with the longer-term implications of the still-fragile Iranian-Saudi rapprochement yet to be fully assessed.

It is difficult to predict where these countervailing trends will take the broader region and this produces an overall environment of uncertainty that offers a complex mix of opportunities and risks. In a new analytical survey of the region's shifting conflict dynamics, the authors identify two escalation risks and two opportunities to promote de-escalation and foster greater regional integration at the current moment.

Contents

I. Background

II. Strategic Assessment and Overview of the Region: Rising Regional Cooperation Amid Persistent Risks

III. Escalation Risk 1: Iran’s Impact on the Regional System

IV. Escalation Risk 2: Israeli-Palestinian Dynamics Destabilizing the Broader Region

V. Opportunity 1: Regional Economic Integration

VI. Opportunity 2: Regional Climate Resilience and Energy Transition Cooperation

VII. Toward a New Strategic Orientation for the United States in the Middle East

VIII. Methodology

IX. Acknowledgements

XII. Endnotes

Key Findings

A nine-month analytical survey of the Middle East’s shifting conflict dynamics by this study’s authors identified two escalation risks and two opportunities to promote de-escalation and foster greater regional integration at the current moment.

Escalation Risk 1: Iran’s impact on the regional system. The March 2023 Saudi-Iranian deal on normalizing diplomatic ties, which Beijing helped broker, has already produced some signs of a further easing of tensions between Iran and the Gulf. But questions remain regarding the long-term sustainability of this de-escalatory trend, including Tehran’s willingness or ability to stick to whatever specific agreements it had reached with Riyadh. Meanwhile, several factors continue to make Iran and its regional activities the likeliest escalation risk in the broader Middle East in 2023: protests inside of Iran producing greater uncertainty about the regime’s approach; the lack of progress in nuclear talks as well as more aggressive steps toward enriching uranium; Tehran’s continued actions to undermine regional security; and Iran’s overt support for and cooperation with Russia in the context of the war in Ukraine.

Escalation Risk 2: Israel-Palestinian dynamics destabilizing the broader region. The Israeli government’s make-up, structure, ideology, and initial political actions have highlighted numerous potential sources of tensions that have already led to escalation inside of Israel, between Israel and the Palestinians, and in Israel’s relations with the wider region. At the same time, Palestinian politics and political institutions are in a state of paralysis and steady decline. In late 2022 and into early 2023, violent incidents (including terrorist attacks, military actions, and settler violence) were on the rise in the West Bank,1 causing many Israeli and Palestinian casualties, and leading regional countries to call for international intervention.

Opportunity 1: Regional economic integration. Compared to other parts of the world, economic cooperation in the Middle East remains relatively nascent, with some recent diplomatic moves creating the potential for greater and more productive cooperation both within the region and between regional states and external powers like the United States. The prospects for regional economic integration now appear brighter than at any point since the mid-1990s due to a confluence of factors: the advent of new regional and international mechanisms like the Negev Forum,2 the India-Israel-U.S.-United Arab Emirates grouping (I2U2),3 and the Baghdad Summit;4 ongoing U.S. diplomacy to resolve bilateral disputes and facilitate multilateral agreements; and the commitment of a number of regional states — most notably energy-exporting Gulf Arab monarchies like Saudi Arabia but also other countries like Egypt — to long-term national development visions. Developing clean sources of energy and managing the transition away from fossil fuels appear to be particular priorities. External actors such as the U.S. can help play a supporting role in efforts like the Negev Forum working groups aimed at advancing economic cooperation, particularly on clean energy, education, food and water security, health, regional security, and tourism. In addition to these mechanisms, the United States, in conjunction with its allies and partners, should explore the creation of other regional diplomatic groupings that could coordinate efforts to manage, mitigate, and de-escalate conflict and tensions.

Opportunity 2: Regional climate resilience and energy transition cooperation. The climate crisis has posed multiple threats to water, food, and energy security worldwide, with the Middle East experiencing a profound number of climate impacts that could disrupt the reliability and sustainability of these essential resources. The 2023 United Nations Climate Change Conference (28th Conference of the Parties, COP28), the next international climate conference, will be held in Dubai, and this presents an important opportunity to encourage greater regional cooperation on a range of climate resilience and energy transition issues. As the United States considers its strategic options to support de-escalation trends, it should keep in mind two key fundamentals. First, any de-escalation that offers only limited benefits that don’t impact the human security condition of millions of people across the region will likely only be temporary, particularly if the arrangements reinforce the power of actors that lack popular legitimacy and support. Second, the United States should avoid the risk of creating too many competing forums and uncoordinated initiatives for engaging the region, particularly at a time when the bandwidth and focus of overall U.S. national security policy are strained by Russia’s war against Ukraine and the chronic challenges of competing with China.

I. Background

The United States continues to adjust its overall strategic approach to the broader Middle East, an ongoing process stretching across several U.S. administrations over the past decade. The Biden administration’s approach has reflected a trend toward promoting regional integration and cooperation among its partners so that the United States can shift its resources to other strategic priorities, such as China and Russia. As the United States continues to shift its approach to the broader Middle East, the region is undergoing a historic transformation with unprecedented opportunities to build new relationships, de-escalate tensions, and foster conditions for stronger integration. At the same time, the region remains on edge because of ongoing tensions in Yemen, Syria, Iraq, and other conflict zones, a civil war that broke out recently in Sudan, along with the overarching challenges presented by fraught relations between Iran, Israel, and several Arab Gulf countries — with the longer-term implications of the still-fragile Iranian-Saudi rapprochement yet to be fully assessed.

Discerning strategic clarity from these countervailing trends of de-escalation taking place alongside continued tensions at a time of geopolitical multipolarity is no simple task.

In the period from September 2022 through the current month, the Middle East has witnessed a series of events with the potential to impact the overall structural stability of the regional state system and how the region relates to the broader world:

-

Public protests against Iran’s regime erupted in September 2022,5 leading to new questions about the inevitable leadership transition that will take place in Iran;

-

The November 2022 election of the most right-wing government in Israel’s history6 added to the uncertainty and volatility of the region;

-

The lack of progress in international talks on an Iran nuclear deal7 exacerbated regional tensions, but a China-brokered deal between Saudi Arabia and Iran8 raised new questions about possibilities for regional realignments;

-

Renewed diplomatic efforts on Yemen9 generated fresh hopes of achieving a negotiated resolution to the conflict there;

-

Civil war engulfed Sudan in April 2023,10 threatening to draw in regional and global actors; and

-

The trend of normalizing relations with the Assad regime in Syria picked up pace with the Arab League inviting Bashar al-Assad to participate in a summit in Jeddah in May 2023.11

It is difficult to predict where these countervailing trends will take the broader region, and new dynamics will surely emerge, with questions looming like who will lead Turkey after the May 2023 elections, what will be the outcome of Israel’s internal political turmoil, and how will the inevitable leadership transitions in Iran, Lebanon, and Palestine play out. This produces an overall environment of uncertainty that offers a complex mix of opportunities and risks. Heightened tensions and insecurity in the region have heretofore often led policymakers in the United States and Europe to adopt a tactical, crisis management mindset that prioritized a focus on threats, rather than opportunities. Yet such a reactive mode would inevitably risk missing the potential to seize emerging opportunities in the regional landscape, including some positive shifts underway that could meaningfully de-escalate conflicts. In this context, it is important for policy planners and policymakers to take on a more assertive approach: They must manage urgent crises while simultaneously finding pathways to proactive policies. The latter should reinforce the positive trends to build on emerging regional realignments and identify areas that might incentivize a de-escalation in tensions across the region and disincentivize escalation or additional conflict.

It is important to keep in mind that overly accommodative efforts to produce de-escalation and normalized relations among regional actors may only provide a temporary or false sense of stability and peace. This is particularly true if, for example, the normalization of ties with the Assad regime in Syria or the China-brokered deal between Iran and Saudi Arabia fail to provide tangible results that improve the human security situation for the millions of people at risk of being caught in a crossfire of regional tensions that could unexpectedly erupt into wider conflicts.

II. Strategic Assessment and Overview of the Region: Rising Regional Cooperation Amid Persistent Risks

The Middle East region is going through a noteworthy period of transformation as dynamics of de-escalation and cooperation coexist with persistent risks of escalation and contestation. After decades where the latter patterns overshadowed the former, it is important that leaders in the region and around the globe understand and encourage the positive trends while managing and reducing the negative ones. This section provides an overview of both sets of trends and offers recommendations for strengthening the former over the latter to set the context for this report.

Conflict and Strategic Reorientation

The past two decades have been a period of acute conflict in the Middle East; the costs of those conflicts, their futility, and lessons learned from them have provided momentum for a more recent period of de-escalation and moving away from conflict as a useful or easy fix for problems. The military operations the U.S. launched in the first decade of the century fell short in achieving many of their stated goals, contributed to disillusionment, and convinced U.S. policymakers, as well as the American public, to favor diplomacy over pyrrhic “military solutions.”12

The escalation of Shi’a-Sunni sectarian tensions, particularly after the invasion of Iraq, led both Iran and a number of Sunni states to back rival sectarian militias throughout the region. While the Iranian regime still persists in this strategy, Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states have generally turned away from backing armed Sunni extremists, realizing that they create risks for their own security, are not effective counters to the threats posed by Iran, and contradict the moderating secularizing and pluralistic direction in which they are trying to move their own societies. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has continued to use Islamist groups when it suits him, such as in Syria and Libya,13 but also pursues diplomacy and moderation elsewhere as he sees fit. How Turkey might change its approach to the region if there’s a leadership transition there this year remains to be seen.

The reduced American footprint and strategic prioritization of the Middle East, and the so-called pivot to Asia and focus on China, started during the Obama administration and continue to this day. An added U.S. focus on Europe after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 further downgrades Washington’s immediate attention to the Middle East, even as it underscores the region’s importance in the broader geopolitical competition for influence underway.

This trend convinced leaders in the region that the U.S. was not going to solve their problems for them and impelled them to undertake initiatives of their own. The impetus for the Abraham Accords came from the UAE itself and then was aided and facilitated by the Trump administration. The turn to negotiation between Saudi Arabia and Iran, as well as the resumption of diplomatic relations between some other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries and Iran, also stems from the realization that the U.S. was not going to provide a “solution” for the challenge of Iran, and that GCC states had to both bolster their own military capacities while also engaging in diplomacy with Tehran to explore areas of conflict management and de-escalation.

The events of the Arab Spring that started in 2011 themselves ushered in a number of conflicts that the countries of the region have only recently begun looking for ways to de-escalate and pull away from.

-

The uprising in Egypt triggered acute tensions between Turkey and Qatar backing the Muslim Brotherhood on one side and Saudi Arabia and the UAE backing the military on the other.

-

The conflict in Libya similarly drew in regional powers on opposite sides.

-

The uprising in Syria soon pitted Iran on the side of the regime, and Turkey, Qatar, and some other GCC countries on the side of the various opposition factions.

-

The conflict in Yemen pitted Saudi Arabia and the UAE backing the Yemeni government against Iran backing the Houthi rebels.

-

In Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and the UAE moved decisively to shore up the embattled government against an opposition that was seen as encouraged by Iran.

-

The Gulf countries fairly quickly gave up on supporting the fight in Syria, the UAE backed out of Yemen, while Saudi Arabia has been looking for a negotiated end to the Yemeni conflict; in Egypt and Bahrain, the contests were settled decisively in favor of state forces.

A Shift Toward De-Escalation?

These two decades of conflict have driven home to leaders in the region the costs and meager benefits of intra-regional conflict as well as given them ample reason to give diplomacy, de-escalation, and attempts at cooperation a chance.

While Iran still sees waging proxy wars through its partner militias in Yemen, Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon as central to its regional strategy, the Gulf countries have generally soured on these proxy conflicts and militia approaches, finding that they are not nearly as good at this game as the Iranians. Even the recent civil war in Sudan has turned out to be illustrative of this fact: Although a number of neighboring and Middle Eastern powers had long cultivated ties with rival factions in Sudan, regional states have thus far instead opted for spearheading a multi-party mediation process14 rather than getting involved in another proxy struggle. For the GCC states, these conflicts create deleterious lose-lose situations; their long-term economic and security interests favor negotiated ends to these conflicts and the re-establishment of state authorities that can restore order, which the Gulf states can then deal with to secure their own stability and pursue their interests.

Turkey is also moving in a similar direction. Though still engaged in limited proxy conflict in places such as northwest Syria15 and western Libya,16 Turkey is otherwise realizing that re-engaging with Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Egypt, and finding diplomatic pathways to addressing its dire economic needs works better than betting on proxy conflicts that have been costly and offered few benefits.

What’s happening in Iran today bears watching closely. Throughout his 34-year rule, Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has pursued a hardline confrontational policy in the region, building on the “successful” model of Lebanese Hezbollah to develop similar client or partner militias in Iraq, Syria, Yemen, and to some degree Gaza, and pouring billions of dollars into sectarian proxy wars, as well as military buildups against Israel. The bulk of the Iranian population, however, has seen no benefits from this policy, and a new generation of Iranians is currently in widespread revolt not only against this strategy, but against the whole ideological Islamic regime that sustains it. What bears watching is where the Iranian regime will go in the months ahead, especially as prospects grow of a leadership transition away from the ailing, 84-year-old Khamenei.17 To ensure a smooth transfer of power, rebuild domestic support for the Islamic Republic regime, and crush opposing voices, the authorities might seek to double down on repression at home while stepping up belligerent activities abroad.

These could be the lessons they have drawn from the survival of the Assad regime in Syria, which might be compounded by a fear that showing moderation now would be seen as a sign of weakness both by opponents at home and abroad. Or — perhaps buttressed by the de-escalatory agreement reached several months ago with Saudi Arabia — Iran may tack toward a more pragmatic direction, as it did when Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, Mohammad Khatami, and Hassan Rouhani were elected president.

It is too early to tell, but it is important to remain engaged with Tehran and to keep communicating the potential benefits that a more moderate and pragmatic foreign policy would bring to Iran, its economy, and its people. If it doesn’t bear fruit in the near term, it is still an important message to send to the various members of the regime, and to the Iranian public at large, as the date of Khamenei’s eventual death approaches.

Systemic and Socioeconomic Drivers Shift the Focus to Human Security

The COVID-19 pandemic has had its own political and geopolitical impacts. For the first time in living memory, the enemy of the state and society was not a foreign country, a rival sect, or a hostile group, but rather a viral pathogen.

The threats from climate change fall into a similar category of an existential threat that doesn’t come from state or non-state adversaries but rather from systemic and natural forces. The massive response to these threats has required a whole-of-government approach and realigned the focus, resources, and values toward public health, climate resilience and adaptation, and energy transition.

All of these policy priorities have shifted attention at least partially away from an obsession with fighting regional foes and toward improved government planning and coordination to face human security challenges, many posed by the natural world. Notably, these threats cannot be addressed individually or within each country’s borders alone; they demand greater regional and global cooperation. The hosting of both COP27 and COP28 in the region indicates the degree to which Middle Eastern governments have moved to the forefront of climate policy planning and their recognition that multilateral cooperation is an urgent necessity.

At the socioeconomic level, the combination of political pressures such as the Arab uprisings, as well as the socioeconomic strains of oil-importing countries — exacerbated by COVID-19 and the double blows of high energy and food prices in 202218 — have supercharged the concern of most regional governments to prioritize economic development. The Arab uprisings, and more recently the uprising in Iran, have made it clear that if they do not provide sustained economic development and opportunities for the large youth cohorts entering the job market, political consequences will follow.

The new “social contract” in most Arab countries after the Arab uprisings doubled down on restricting political voice and participation but sought to compensate for that by promising and/or providing economic opportunity. Wealthy GCC states like Saudi Arabia have moved rapidly along that path, but even countries like Egypt have sought to spur economic development to counterbalance the narrowing of political space; so far, however, the majority of the population has seen little socioeconomic benefit.

The Role of Regional Actors Amid Changing Dynamics

This focus on domestic socioeconomic development is part of the new ethos, as regional powers have given up on dreams of reshaping or dominating the Middle East and shifted their focus to their economies. Much of this domestic development requires a more peaceful region, and elements of cooperation among states, and certainly between Middle Eastern actors and global powers like the U.S., China, Russia, and the European Union. Only Iran still seems focused on grand regional ambitions, rather than domestic development, even while paying a heavy price for it at home.

Israel has played a role on both sides of the escalation/de-escalation spectrum. It remains in a state of occupation and conflict with the Palestinians, and in a state of conflict with Iran and its proxies in the Palestinian territories, Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq. The risk of a major war in the region along the Iran-Israel axis has not gone away.

On the other hand, the Arab-Israeli conflict is largely a thing of the past; Egypt and Jordan signed peace agreements decades ago; and the UAE, Bahrain (with Saudi blessing), Morocco, and Sudan recently normalized relations with Israel as part of the Abraham Accords.19 These accords present an opportunity to bolster cooperation in the region in many sectors, including technology, agriculture, communication, transportation, education, energy, climate adaptation, and investment.

But it is important that leaders in the region and internationally pursue initiatives in which these accords create conditions conducive to a political process that protects Palestinian rights, promotes conflict mitigation, and supports Palestinian political coherence while encouraging movement toward a two-state solution, rather than further isolating the Palestinians and giving Israeli leaders the impression that they can ignore the Palestinian issue since Arab states are normalizing relations with them anyway. The Palestinian issue remains a major flashpoint among populations across the region and could quickly unravel any openings in relations made at the governmental level without a more concerted effort to produce a just, equitable resolution to the conflict. The inclusion of extreme right-wing elements in the new Israeli government and its actions over the past several months demonstrate how attempting to normalize and stabilize the Middle East while the bulk of the Palestinian population is under occupation is not a sustainable pathway.

While Turkey and the majority of Arab countries have opened dialogues with Tehran and could imagine some form of coexistence with the Islamic Republic, Israel still considers it an existential threat. The Israeli position is understandable, as Tehran is openly committed to the destruction of the Israeli state and considers “death to Israel” an ideological pillar of the regime.

There remains a significant risk of an Israeli-Iranian conflict and a subsequent region-wide war, triggered by the unresolved trajectory of Iran’s nuclear program. So far, it has been the U.S. — and its P5 partners (the United Kingdom, France, China, and Russia) — that have tried to deal with the Iranian nuclear issue. The 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) provided an answer to the problem, at least temporarily. President Donald Trump withdrew from the deal in 2018, but without having a viable alternative to manage the nuclear threat. The Biden administration’s attempts to revive the deal have not borne, and are unlikely to bear, fruit. Meanwhile, Iran has broken out of previous JCPOA provisions and is enriching closer and closer to weapons-grade fuel.20 The region is on a dangerous path.

With no imminent return to the JCPOA, unless Iran shows restraint and stops enrichment at a reassuring level, Israel may contemplate additional military actions beyond the steps it has already taken with covert action. Indeed, there have been growing signs the Netanyahu government may be preparing to preemptively strike Iran’s nuclear program.21 An Israeli attack will not destroy Iran’s nuclear effort, although it might set back Iranian capabilities by a few years; but it would likely draw in American military engagement of some sort and at least create a new set of conditions for Tehran.22

As discussed in the final section of this report, experience, diplomacy, and mediation can play an important role in helping these troubled societies find new modes of power sharing and post-conflict governance. While the U.S., Russia, and China are increasingly driven toward great power competition and may import those rivalries into the Middle East, there remain opportunities to encourage regional diplomacy, de-escalation, and cooperation. In this pursuit, partners in countries such as Oman and Kuwait, as well as Egypt and Morocco, and even in some previously more confrontational states such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar, and Turkey can be sought after to bring about meaningful de-escalation in the MENA region.

III. Escalation Risk 1: Iran’s Impact on the Regional System

Several factors make Iran the likeliest escalation risk in the broader Middle East in 2023:

-

The protests that erupted in mid-September 2022, in reaction to the murder of a young Iranian woman in detention, underscore deep social discontent, especially among the young, with the Islamic Republic.23 This creates a heightened sense of uncertainty as an eventual leadership transition from Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei looms on the horizon.

-

The lack of progress in international talks on Iran’s nuclear program, combined with increasingly assertive steps to enrich its stockpiles of uranium,24 adds to the sense of insecurity about the situation in Iran and how it might affect the wider region.

-

Iran’s continued support to actors across the Middle East that undercut stability, national sovereignty, and the overall state system adds to the risk of regional escalation.

-

Iran’s overt support for and cooperation with Russia in its war against Ukraine25 produced a dynamic where the U.S. and Europe have become more aligned in seeking to isolate Iran for its actions in the international arena as well as its human rights abuses and repression at home.

This section will identify key factors for potential escalation involving Iran and point to concrete actions that international actors could take to prevent wider escalation. In addition to broader regional dynamics with Iran, this section will provide additional analysis and suggestions on two countries that are important arenas for regional competition and conflict, Iraq and Yemen.

Four Factors that Could Produce a Wider Regional and Global Escalation with Iran:

1. Internal protests create more uncertainty. Widespread protests against the ruling regime in Tehran began in mid-September 2022, after the death of a young woman, Mahsa Amini, held by police for violating the country’s mandatory religious dress code. These protests continued into early 2023. By early spring, the regime crackdown managed to mostly crush the mass street protests, but anger, especially among the younger generation, has persisted and continues to materialize as individualized demonstrations or shows of defiance. In any case, the protests have served to highlight the regime’s poor human rights record and caused the United States and European Union to level additional sanctions against it.

The Iranian regime has blamed the protest movement on foreign powers and, in December 2022, began executing protesters.26 Since the opposition activism targets one of the regime’s core ideological pillars, and indeed the regime itself, its persistence likely heightens the chronic insecurity perceived by those in power in Tehran. This insecurity could in turn lead Iran to adopt a more aggressive posture in the region in hopes of creating a sense of security among regime leaders, or at least a sense that they are striking back against their foreign enemies. They may also intend to produce a “rally around the flag” effect among ordinary Iranians and mobilize regime supporters. Conversely, the protests could motivate Iran’s leaders to pull back from the region as they focus more on shoring up their position at home.

2. Possible escalation with Israel due to Iran’s nuclear program and wider regional tensions. Iran’s recent moves to step up its enrichment efforts and its deficient cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), combined with the lack of progress in nuclear talks, raise additional concerns about regional escalation. The Israeli government, as described in Section IV of the report below, may step up its rhetoric and actions in response to Iran’s moves on its nuclear program and the lack of progress in international diplomacy.

In addition, Iran continues to pose a potential threat to Israel due to its ongoing support for actors in Syria, Lebanon, and the Palestinian territories. Iran also threatens international navigation in the Persian Gulf, Gulf of Oman, and the Red Sea, as illustrated once again by the recent seizures of two oil tankers near the Strait of Hormuz, in retribution for earlier U.S. seizures of two Iranian oil carriers on suspicion of smuggling.27 Similarly, Iranian-supplied groups in Yemen, acting independently, have already threatened freedom of navigation in the Bab el-Mandeb strait, with merchant vessels and U.S. Navy ships coming under attack while sailing in the Red Sea.28

3. Escalation along Iran’s borders. Several times last year, Iran launched multiple ballistic missile and suicide drone attacks against Iranian Kurdish groups29 and alleged Israeli intelligence operations based in Iraq’s Kurdistan region. The first of these strikes hit near the American consulate in Erbil, while Iranian refugees were killed in the September attacks.

In addition, the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan, especially at first, exacerbated Tehran’s perception of potential threats to its sovereignty from Afghan territory30 as well as long-standing Iranian concerns about possible threats from Pakistan’s Baluchistan region.31

The Iranian regime is also worried about possible threats from its north, including the South Caucasus. Israel and Azerbaijan have forged a close defense and diplomatic relationship over the years, with Israel serving as Azerbaijan’s largest arms supplier and Azerbaijan recently opening an embassy in Israel.32 Tensions with Azerbaijan escalated sharply in early 202333 and rumors persist that Azerbaijan has granted the Israeli military access to its airspace and use of air bases in the event of a conflict with Iran. And to put further pressure on Tehran, this past April Israel opened a permanent embassy in Ashgabat, Turkmenistan.34

Iran’s leaders have sought to link these possible external threats along its borders to the internal protests that began in September 2022 and have at times publicly framed these efforts as trying to foment civil war and challenge the legitimacy of the current Islamist regime in Tehran.

4. Broader geopolitical tensions due to Iran’s open support for Russia’s war against Ukraine. Iran’s coordination with Russia is producing a backlash in the form of more sanctions and greater isolation from the United States and EU countries. Tehran’s move to more closely align with Moscow at this time complicates the willingness or ability of Western governments to diplomatically support the limited openings that exist for promoting de-escalation and avoiding a wider conflict in the Middle East that would involve Iran.

Limited Openings to Support De-Escalation with Iran

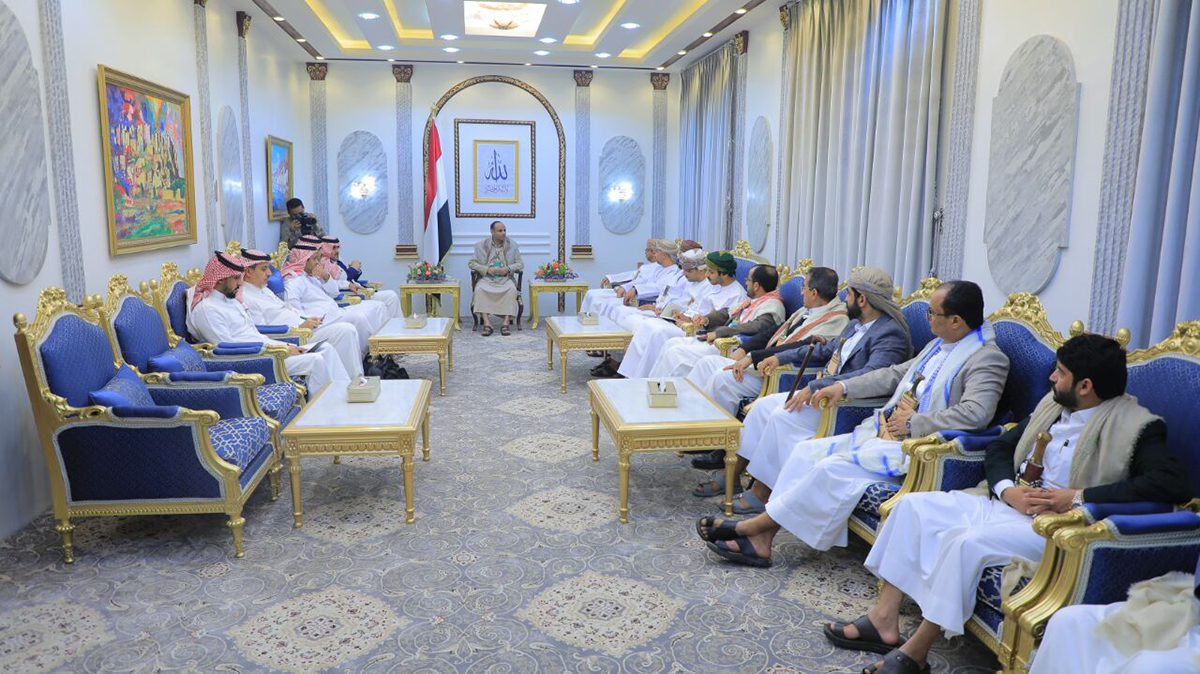

1. Arab Gulf States show a stronger desire for de-escalating tensions. Chronic uncertainty in the region, waning U.S. interest to become involved, along with a series of attacks on Saudi Arabia and the UAE over the past three years by Iran and Iran-backed groups, incentivized new diplomatic openings and talks between Iran and several Gulf states. Those trends finally culminated, on March 10, with the signing in Beijing of an agreement by high-level Saudi and Iranian representatives to re-normalize bilateral relations between the two Middle Eastern countries.35

2023 is proving quite dissimilar to 2013 in terms of regional tensions. In 2013, many Gulf states expressed serious concerns about Iran’s malign behavior in the region, including its nuclear program, but they also had strong reservations about the Iran nuclear talks and the 2015 agreement that resulted from them.

During the past year, on the other hand, the Gulf states repeatedly expressed their support for international diplomacy on Iran’s nuclear program, and they looked for ways to de-escalate the regional situation on multiple fronts. Notable reaffirmations of the GCC’s support for nuclear talks came in February 2023, in a U.S.-GCC Iran Working Group Statement that welcomed diplomatic efforts by the United States and other actors to address Iran’s nuclear program.36

This new posture by the Gulf states offered an opening for creative preventive diplomacy to help foster de-escalation. The initial alignment between Israel and the Gulf states took place under different conditions and was focused on the threat posed by Iran, but the two sides do not share the same threat assessment today as they did a decade ago. And efforts by key regional actors, including Iraq and Oman, laid the crucial groundwork for a final normalization deal brokered by China earlier this year.

The main impetus that drove the UAE and Saudi Arabia to talk to Iran was the desire to avoid a conflict, and this is a key dynamic that should now continue to be encouraged by America and other international actors. Saudi Arabia and Iran want different things from the ongoing talks: Iran likely wants to re-establish economic ties with the Gulf Arab states and widen differences between these countries and the United States, while Saudi Arabia wants Iran to refrain from attacks against the kingdom. Moreover, Riyadh feels that Tehran still aims to export its revolution across the region, while the Iranian regime feels chronically insecure and under threat — a dynamic that was only exacerbated by the recent protests and is unlikely to change until the revolutionary generation in Iran passes from the scene.

As the March Saudi-Iranian rapprochement makes clear, there does appear to be a general interest in diplomacy and de-escalation from Riyadh and Abu Dhabi — though it remains to be seen the lengths to which the regime in Tehran will reciprocate and maintain the momentum for warmer relations with the Gulf. Moreover, the strong desire by some of the Gulf states — namely the UAE, Oman, and Qatar — to push for stronger economic ties with Iran is an area that Western powers can encourage. The Gulf states are looking to help the next generation of Iranian leaders accept the need for political modernization in Tehran, and improving the living standards of the Iranian people is part of any such renewal. The cash-rich Gulf states see investing in such an Iranian political modernization, through economic cooperation, as a win-win scenario.

2. Israel has an interest in maintaining the Abraham Accords and pursuing additional historical openings across the region. Despite the concerns about the Israeli government outlined in the next section, Israel has an interest in keeping ties open with Gulf states such as the UAE and Bahrain, and it seeks to open up relations with Saudi Arabia, Oman, and, eventually, Kuwait and Qatar. If Israel is seen as taking steps that are too aggressive on Iran and that prompt Tehran to target some of the Gulf states, then this could harm bilateral ties between Israel and the countries it has open relations with as well as those it seeks to build relations with in the future.

3. Iran may be looking inward and could adopt a more modest regional strategy. Particularly if the current Gulf-Iranian rapprochement holds, the regime may decide to pull back from its destabilizing regional activities to focus more on domestic political problems. The regime’s backing for the regional proxy model, including the transfer of funds and weaponry, has persistently resulted in greater political costs for the leadership in Tehran. This is true both in terms of the Iranian public’s resentment toward such regional policies, as well as in terms of the foreign counter-responses (such as sanctions) that it has had to endure. Questions of political succession will loom large in Tehran’s calculations going forward. A lengthy succession process involving major state security organs like the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) may give them little time and energy to dedicate to foreign activism, either leading to a general downturn in activity or giving commanders on the ground opportunities to take greater risks than they might otherwise.

However, another scenario involves the regime attempting to address its own insecurity by taking a more aggressive approach abroad. This activism would primarily be intended to strike back against the regime’s perceived foreign enemies, which it holds responsible for the unrest at home. Greater Iranian regional activism could also serve as a rallying point for regime supporters demoralized by the ongoing protests and poor economic prospects, or as a way for those jockeying for power and influence in a post-Khamenei regime to assert their own claims.

Steps/Policy Recommendations

- Incentivize restraint by the Iranian regime. Once there is an opening, engage in quiet diplomatic efforts with elements in Iran’s government who argue for more restraint in Tehran’s regional and global engagement and favor focusing on the country’s domestic economic crisis. Certain figures in the regime might be better placed to act as negotiators and messengers, but they will only be empowered and willing to do so if Supreme Leader Khamenei himself decides to engage in such a dialogue with the West. This is not presently the case.

- Encourage talks to de-escalate regional tensions. Encourage the Gulf states as they build their diplomatic ties with Iran, open and expand teams at embassies, and continue quiet conversations already underway aimed at building trust and confidence in the region. But closely monitor this process to ensure that the Gulf-Iranian diplomatic rapprochement does not free Iran to ramp up its proxy attacks on Israel and U.S. interests in the region or enable it to refocus on suppressing dissent at home.

- Look for diplomatic pathways to address Iran’s ongoing nuclear program while continuing to prepare deterrence options. The Biden administration has not developed a plan B to replace its initial plan to rejoin the Iran nuclear deal. It should continue to look for possible diplomatic pathways to prevent Iran from obtaining fully operational nuclear weapons while simultaneously staying engaged in regional security efforts to enhance deterrence against Iran on all fronts.

- Support quiet efforts to reduce tensions between Israel and Iran. Work in coordination with the United States and European partners to encourage Israel’s government to collaborate with other regional powers to support de-escalation and avoid unnecessary tensions. Effective diplomacy should be backed by regional security efforts to help partners like Israel defend themselves from continued threats.

Iraq: A Key Arena for Competition

Background

Following the October 2021 parliamentary elections, Iraq entered a year of political instability during which the country was held hostage to a test of wills between two opposing Shi’a political coalitions, the Sadrists led by the cleric and political leader Muqtada al-Sadr and the Iran-aligned Coordination Framework (CF) led by former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki. The Sadrists won 73 of the 329 seats in the elections, making them the largest party in parliament.37 For eight months, Sadr tried to form a majority government in alliance with the winning Sunni and Kurdish political parties, thus sidelining the CF.

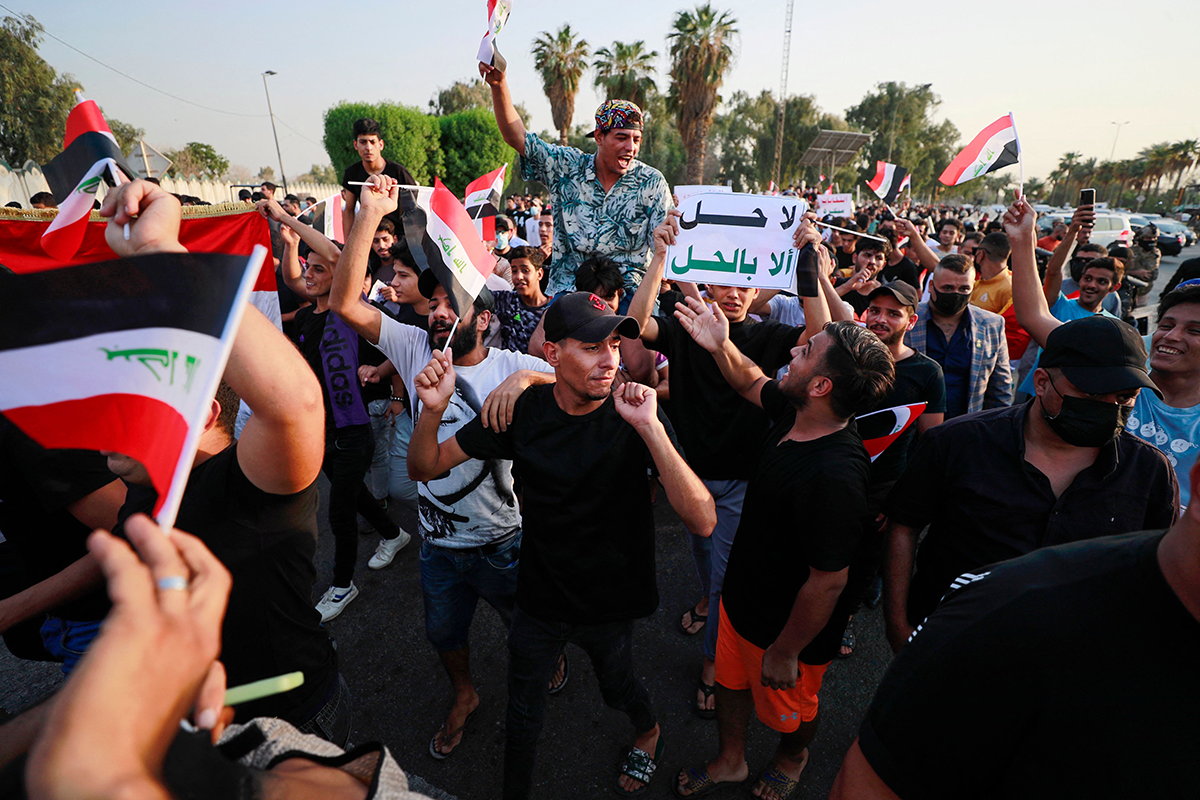

This effort ultimately failed and in June 2022 Sadr asked his party’s MPs to submit their resignations,38 saying he would go into opposition. In line with the election law, the Sadrist deputies were replaced by candidates who won the second-highest number of votes in the same districts, enabling the CF to claim it now had the largest bloc in parliament and could nominate a prime minister. After the CF nominated a candidate on June 25, Sadrists stormed Baghdad’s Green Zone and took over the parliament building. By August, street fighting erupted between Sadrists and CF supporters.39 The crisis was resolved by the intervention of Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani’s office, which called on Sadr and his followers to stop the violence. This crisis demonstrated the limits of outside parties in influencing dynamics on the ground. The U.S. was largely missing in action until the sectarian violence attracted the attention of senior policymakers.

In terms of foreign policy, the CF-led government of Mohammed al-Sudani has maintained policies of neutrality in regional and international conflicts; sought to deepen ties with Arab countries40 including the GCC, Jordan, and Egypt (especially in the economic and energy fields); and promoted dialogue to de-escalate conflicts in the region. Sudani also maintains a warm relationship with Iran and Tehran views him and his political allies positively. Previously announced plans to connect the electricity grids of Iraq and Saudi Arabia have not yet been completed, and Iraq still relies on Iran for both electricity imports and natural gas to operate its power plants. Certain political parties within the CF and their armed wings continue to be wary of foreign investment, especially that coming from Arab Gulf countries.

The U.S. and Iran, long considered the two outside actors with the most political influence in Iraq, have had difficulties exercising that influence in Iraqi politics. American attention has been focused elsewhere, especially since the invasion of Ukraine, and Iraqi political actors’ own cost-benefit calculations increasingly drive the country’s political trajectory. While Tehran still has a large footprint in Iraq, the recent political crisis forced the Islamic Republic to come to terms with the limits of its influence. Iran’s maximalist aim remains to ensure a united Shi’a front as a guarantee against the return of an Arab nationalist regime in Iraq. Since the 2019 protests, which demonstrated clear opposition in Shi’a-majority provinces to Iranian policies, and following the 2020 demise of Qassem Soleimani, the principal architect and enforcer of Iran’s regional policies, Tehran has not been able to insert itself in the management of Iraq’s political affairs in the same way it once did. While the more decentralized approach that followed creates incentives for local actors to refuse to comply with Iran’s directives, it also opens more space for members inside the Iran-aligned network to embed themselves in the economic and political life in their own countries as Hezbollah has done in Lebanon — a model the Hashd al-Shaabi is following in Iraq.

The March 2023 China-brokered Saudi Arabia-Iran agreement should help to ease regional tensions in the Gulf to Iraq’s benefit, but it is unclear how long-lasting and wide-ranging the impact will be. Moreover, the deal does little to address long-standing concerns about Iran’s nuclear and ballistic missile programs and regional proxy network. Attacks on U.S. forces in the region by Iran-backed proxies have continued since mid-March, underscoring the ongoing potential for escalation between Washington and Tehran, which would likely have serious ramifications for Baghdad.

Potential flashpoints in Iraq

-

A confrontation between Sadr and the governing coalition: Sadr is biding his time, waiting for the government to fail in delivering on its promises to fight corruption, create jobs, and improve service delivery. Already six months in power, the Sudani-led government has so far bought time and patience from the Iraqi people by embarking on a massive public hiring program, which in the long term does not bode well for the economy. The government has been helped by high oil prices.

-

The ongoing political crisis between the main Kurdish political parties turning violent: Over the past year and a half, tensions between the two main Kurdish parties, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), have gone from bad to worse, exacerbated by differences over the distribution of oil income, electoral reforms, and security matters.41 The tensions could potentially lead to a return to the violence of the early 1990s between the KDP and the PUK. The PUK has long insisted that most of the region’s oil income remains in the KDP’s hands and it is being denied its fair share.

-

A crisis between the Kurdish region and Baghdad over oil revenues and budget shares: The more severe the intra-Kurdish crisis becomes, the weaker the position of the Kurdish leadership will be in negotiations with Baghdad over issues like a new oil and gas law. Baghdad has threatened to take oil companies operating in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) to court. An agreement was reached on two major points of contention between the two sides — the resumption of oil exports to Turkey from the KRI following a late March ruling by the International Court of Arbitration that halted them42 and the Kurdistan Regional Government’s share of the 2023 federal budget43— but oil exports to Turkey have not yet restarted and the draft budget, which was submitted to parliament for approval in mid-March, has not yet been approved.44

-

Iraq’s worsening water crisis: Considered the fifth-most-vulnerable country to climate change,45 Iraq faces a severe and growing water crisis, driven by reduced rainfall, higher temperatures, and government mismanagement and waste. The problem has been exacerbated by damming in neighboring Iran and Turkey, further reducing available surface and groundwater supplies and increasing desertification. The problem is only expected to get worse going forward: According to the World Bank, freshwater availability in Iraq is forecast to fall by a further 20% by 2050.46 This is likely to have a major impact on the agriculture sector, which accounts for 5% of GDP but 20% of employment,47 as well as food security and the vital oil industry. Nearly one in five people in Iraq live in areas affected by water shortages, according to the U.N., and water shortages and the decline of agriculture are fueling rural-urban migration. Having long ignored the problem, the Iraqi government is finally starting to pay attention and take the issue seriously. The water crisis is increasingly becoming a threat multiplier and could potentially undermine peace and security in Iraq in the near term.

To de-escalate and avert these potential flashpoints, the U.S. and like-minded Western nations should encourage Arab Gulf countries — primarily Saudi Arabia and the UAE — to deepen their economic involvement in Iraq. The two countries are already taking some steps in that direction. Last October, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman announced the Saudi Public Investment Fund will set up regional investment companies in five countries to include Iraq, capitalized at $24 billion total and targeting multiple strategic sectors like infrastructure, real estate, healthcare, financial services, manufacturing, and technology.48 In February 2023, Iraq awarded several contracts to develop oil and gas fields to the UAE-based company Crescent Petroleum, and Saudi and Iraqi officials have held several meetings in recent months to discuss efforts to expand economic cooperation.49 The deeper Iraq becomes integrated with its Arab Gulf neighbors’ economies, the more successful these countries will become at contesting and eventually challenging Iranian influence in Iraq’s domestic politics.

The March Saudi Arabia-Iran deal, although brokered by China, built on Baghdad’s efforts under the previous government to foster Saudi-Iranian dialogue. Western actors should support Iraqi efforts to continue such talks moving forward with the aim of further easing regional tensions, and recent reports indicate that Baghdad has convened a few rounds of official Egyptian-Iranian talks as well.

Addressing the growing water crisis in a serious way will require a sustained regional dialogue involving all riparian states in the Euphrates and Tigris river basins, including Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran. At present, these states tend to deal with water issues on a bilateral basis, but a multilateral framework needs to be established, potentially involving an outside mediator like the UN or an EU country, to help provide international expertise, address the multifaceted challenges involved, and navigate the four countries’ varying agendas.

The U.S. and its European partners have limited options when it comes to Iran, especially as Tehran doubles down on its turn to the East. Open dialogue channels can provide ways to better understand what is taking place inside Iran — especially inside the regime’s different power centers — and also help to avoid unnecessary military escalation.

Yemen: A Tenuous Calm

The civil war in Yemen is now well into its eighth year. While the country has experienced a tenuous calm since a ceasefire was agreed in April 2022, the Houthis have maintained pressure on the government, including by attacking oil facilities in government-controlled regions. Notably, the Houthis have not resumed cross-border attacks while the Saudis have also refrained from relaunching their air campaign.

Omani mediators have worked since late 2022 to promote direct Saudi-Houthi discussions. As part of that effort, Saudi and Omani delegations traveled to Sana’a in early April for direct talks with Houthi leaders. The talks concluded in mid-April and nearly 900 detainees held by the government and the Houthis were subsequently freed as part of a three-day prisoner exchange.50 Houthi spokespersons have reported that the negotiations have made progress. Further discussions are expected to be held and top U.S. officials have traveled to the kingdom in recent weeks to advance Yemen peace efforts.51 Diplomats also continue to pursue Yemeni-Yemeni negotiations for an extended ceasefire that would allow for talks on a framework for political dialogue to begin, but an agreement has not yet been reached.

While there have been some expressions of optimism that a renewed or expanded ceasefire could lead to a sustainable resolution of the conflict, there are still considerable grounds for skepticism. The Houthis have consistently failed to fulfill their commitments undertaken in previous negotiations stretching back at least to the Stockholm Agreement of 2019. They have also insisted on putting maximalist demands on the negotiating table, including a demand that the internationally recognized government pay not only civil service salaries in both the north and south but also that it pay Houthi militias — effectively requiring the Yemeni government to pay the salaries of those trying to overthrow it.52 In short, the Houthis have not engaged in good faith negotiations in the past and, in all likelihood, will not fulfill any agreements they make in the absence of external pressure.

Riyadh has made its desire to extricate itself from the war clear, but even a long-sought Saudi military withdrawal would not resolve the conflict and ignores its underlying domestic drivers.53 Yemen’s civil war began in September 2014 with the Houthi takeover of Sana’a, well before the Saudi-led coalition’s military intervention in March 2015. Even in the event of a Saudi withdrawal, the conflict could continue in an increasingly localized manner. The Houthis might opt to resume their military campaign at some point in the future54 and other local actors involved in the conflict, like the Southern Transitional Council, have said they won’t be party to any Saudi-Houthi agreement.55

As part of the March 2023 Saudi Arabia-Iran deal, Tehran reportedly agreed to stop arming the Houthis and discourage them from carrying out cross-border attacks into the kingdom.56 There are question marks over Iran’s willingness and ability to maintain these commitments, especially given its track record of violating the arms embargo laid out in U.N. Security Council Resolution 2216. At the end of the day, Tehran has made significant strategic gains through its support for the Houthis and is unlikely to give them up just because of its agreement to normalize diplomatic relations with Riyadh. The Houthis have also sent a series of recent escalatory signals to emphasize their autonomy from Tehran and distance themselves from the Saudi-Iran deal.57

Moving forward, the United States and international actors should continue to support the U.N. diplomatic effort — any lasting solution to the conflict will need to bring all parties together. They can also reassert their support for the unity and sovereignty of Yemen as well as regional security and stability; whatever de-centralization or federalism may ultimately arise from a negotiated settlement, right now unmanaged and conflict-driven fragmentation only harms the prospects for de-escalation.

Despite the U.S.-Russia confrontation over Russian aggression in Ukraine that has brought almost all scope for agreement in the U.N. Security Council to a halt, Yemen is one issue where Moscow and Washington can find common ground. Recent discussions on Yemen at the Security Council have underscored the need to resume the political process to take advantage of the space created by the lack of large-scale fighting.58 International support from donors like the U.S. for the humanitarian and protection assistance program on which two-thirds of the population relies also remains essential; the U.N. estimates the total cost of the program this year will be $4.3 billion.59

The United States and others can additionally support efforts to reduce the effects of Yemen’s conflict on the local level, such as supporting the negotiation of local ceasefires and peace initiatives — the Women’s Peace Initiative in Taiz represents one such case. The conflict does not rage across the entire country, and that opens opportunities to jumpstart economic and capacity-building activities where it does not.

IV. Escalation Risk 2: Israeli-Palestinian Dynamics Destabilizing the Broader Region

Israel

Israel’s November 2022 election, the country’s fifth in three and a half years, produced a clear victory for Benjamin Netanyahu and his right-wing bloc, which secured 64 seats in the 120-seat Knesset.60 The coalition Netanyahu has assembled, comprising Likud, Religious Zionism, Otzma Yehudit, Noam, and the ultra-Orthodox parties Shas and United Torah Judaism, is the most right-wing in Israel’s history. Even before the government was formed on Dec. 29, as coalition talks were still underway, concerns were already being raised in the U.S., EU, Jordan, the Palestinian Authority (PA), and within Israel itself about the new government’s composition and policies, including potential risks to Israel’s democracy and escalation between Israel and the Palestinians. The concern within Israel has led to an evolving movement of pushback against democratic erosion.61

The inclusion of extremist elements like Itamar Ben-Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich, both of whom received key government portfolios with jurisdiction in the occupied Palestinian territories, added fuel to the fire. Ben-Gvir heads the newly expanded Ministry of National Security, which has far-reaching authority over police in both Israel and the occupied West Bank, while Smotrich is a minister within the Ministry of Defense (in addition to his role as finance minister) with authority over both Israeli settlements and Palestinian civilian matters in the occupied West Bank.

During the government’s first months in office these two ministers already sparked tensions between Israel and its neighbors — Ben Gvir’s visit to the al-Aqsa Mosque compound/Temple Mount in January was condemned by multiple Arab states,62 and his insistence on speaking at the Europe Day event in Tel Aviv in May led the EU delegation there to cancel the planned diplomatic reception.63 As for Smotrich, his remarks in March that there is no such thing as a Palestinian people64 and his verbal support for settler violence65 also created difficulties for Israel with its Arab neighbors and allies in the West.

Palestine

Palestinian politics and political institutions are in a state of paralysis and steady decline. The Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC), which had ceased to operate since the Hamas-PA split of 2007, was officially dissolved by President Mahmoud Abbas in December 2018. Since then, Abbas, whose presidential term officially expired in 2010, has ruled by decree, with little or no institutional oversight. The absence of institutional politics and the growing authoritarianism of the PA, along with the ongoing political and territorial split with Hamas and the lack of a political horizon for ending Israel’s 55-year-old military occupation, have severely eroded the legitimacy of both President Abbas and the PA.

The last-minute cancellation of planned legislative and presidential elections in April 2021 and the killing a few months later of Nizar Banat, a popular political activist and outspoken critic of Abbas, have further raised public skepticism and frustration with the leadership. Meanwhile, the embattled Palestinian leadership has been plagued by a widening economic crisis and chronic budget shortfalls spurred by a dramatic decline in international aid over the last decade and Israel’s withholding of tax transfers collected on behalf of Palestinians.

The political and economic stagnation in Palestine comes against the backdrop of rising violence and deteriorating security conditions throughout the Occupied Territories. This includes three separate Gaza wars in the span of two years (May 2021, August 2022, and May 2023), regular clashes between Israeli security forces and Palestinian protesters in East Jerusalem, a dramatic spike in Israeli settler violence against Palestinians,66 as well as a series of terrorist attacks on Israelis by Palestinians since the spring of 2022. Moreover, the months-long crackdown by the Israeli army against Palestinian militants and other resistance elements in the West Bank and what appears to be a low-level armed rebellion concentrated in the northern West Bank towns of Nablus and Jenin poses serious security challenges for Israel’s occupation as well as the political viability of the PA and its security coordination with Israel. More than 200 Palestinians, mostly civilians, were killed by Israeli forces and settlers over the course of 2022, including 152 in the West Bank,67 making it the deadliest year for Palestinians there since 2005.

Risks for Escalation and Potential Flashpoints

The new Israeli government’s make-up, structure, and ideology have highlighted numerous potential sources of tensions that might lead to escalation inside of Israel, between Israel and the Palestinians, and in Israel’s relations with the wider region. Indeed, some sort of escalation on at least one of these fronts may be inevitable.

Tensions inside of Israel

Far-right ideology, populism, and religion are dominant factors in the Netanyahu government. Coalition bargaining in the weeks following the election gave the Israeli public a glimpse into the new government’s policy and budgetary priorities, as well as an understanding of how ministerial responsibilities would be reshuffled and assigned. The risks of domestic escalation became clear around the same time too: verbal attacks by members of the incoming coalition on state institutions, including Supreme Court judges and Israeli army generals; backing by far-right politicians for statements and actions against Arabs; protests by dozens of municipalities against letting a far-right and anti-LGBTQ member of the Knesset (MK) control external school programming; threats against opposition activists; plans for legislation that will weaken the judicial system and limit civil society; and promises to ultra-Orthodox parties to legitimize gender segregation.68

Once in power, Netanyahu’s cabinet proceeded to implement their divisive electoral promises and act on some of their most extremist coalition members’ charged rhetoric. Among the most notorious actions and initiatives have been Ben-Gvir’s visits to the Temple Mount/al-Aqsa Mosque site in Jerusalem in January and May, a spike in often deadly crackdowns and raids in the West Bank and East Jerusalem, as well as attempts to advance a judicial reform package through the Knesset that would, inter alia, allow the government to appoint Supreme Court judges.69

Many in Israel have a sense that they are witnessing a game-changing moment in the country’s history — one that is decidedly for the worse — while also feeling disenfranchised by the almost non-existent parliamentary representation of the Israeli left and disillusioned by the splits and personal animosity within the anti-Netanyahu bloc. Those committed to liberal democracy in Israel are seeking ways to react, resist, and protest. Since December 2022, this has served as a catalyst for a variety of uncoordinated grassroots opposition actions, culminating in weekly protests that have gradually grown in size and have continued for more than four months now. With increasing polarization and calls for civil disobedience on the rise, Netanyahu felt compelled to announce a “time out” in the legislative process, and sought to divert attention elsewhere. But with the Knesset now back in session, the government will again seek to push its legislative agenda forward.

The danger of an outbreak of violence between Jews and Arabs in Israel remains high. It could happen as a result of an individual act of hatred provoking a response and spiraling out of control, new government policing policies creating pushback, or potential violent incidents in the West Bank, Gaza, or Jerusalem prompting a wider reaction.

Tensions between Israel and the Palestinians

Israeli-Palestinian escalation in the West Bank was already apparent and underway during the previous Israeli government. But since the new government took office in late 2022, violent incidents (including terror attacks, military actions, and settler violence) have intensified, causing many casualties, especially on the Palestinian side, and leading regional countries to call for international intervention. The current trends are quite negative in terms of violence, settlement expansion, evictions, demolitions, or land confiscations. Nevertheless, preventive diplomacy assisted by the U.S., Egypt, and Jordan, managed to contain escalation and avoid a flare-up during the sensitive overlap between Ramadan and Passover, in April.

The coalition agreements increase the risk of Israeli-Palestinian escalation. Some key authorities related to the occupation were stripped from the Ministry of Defense and transferred to ministries led by the far-right. Smotrich has authority over the Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT) and the Civil Administration,70 and Ben-Gvir wields authority over the border police in the Palestinian territories.71 Moreover, he is pushing to create a separate security force, the National Guard, which would answer directly to him as security minister. These changes, coupled with an expected tacit green light for settler violence, settlement expansion, creeping (and increasingly de jure) annexation, and intensification of demolitions and evictions against Palestinians, all constitute risks for a flare-up. Netanyahu, however, does not seem to be interested in a flare-up that goes beyond the scope of his immediate goals; and for the sake of this, he has agreed to engage with the PA through the regional security summits convened in February72 and March 2023.73 These U.S.-led summits were a unique occurrence in which such a right-wing coalition officially met and negotiated with the PA, in an effort to promote stability. Nevertheless, escalation in the Palestinian territories is also occurring as a reaction to Jewish-Arab incidents within Israel, intra-Palestinian power struggles over a transition in leadership, visits by far-right politicians to the al-Aqsa Mosque compound/Temple Mount, and the rise of new Palestinian armed groups (e.g. Lions’ Den).74

Within his new coalition, Netanyahu maintains control over key security decisions and tries to limit his coalition partners from taking too many destabilizing steps (while publicly making problematic promises — not likely to be fulfilled — such as enabling Ben-Gvir to control a “National Guard”). But he clearly lacks sufficient leverage over far-right MKs determined to continue their provocative actions, as exemplified by the intensified crackdown in the West Bank, the provocations at the al-Aqsa mosque (including beatings of worshippers during Ramadan, although this was reversed in the final 10 days of the month, during which Netanyahu prevented visits by non-Muslims and limited police actions), settler terrorism like the rampage in Huwara this past March,75 the unprecedented death in a hunger strike of imprisoned activist and former spokesperson for the Palestinian Islamic Jihad Khader Adnan.76 Netanyahu used the May 9-13 round of warfare with Palestinian Islamic Jihad in Gaza to showcase that he is responsible for making key decisions, appeasing Ben-Gvir while carrying out a military operation that did not yield much regional condemnation and succeeded in keeping Hamas out of the cycle of violence.

Some potential flashpoints to watch in 2023 include:

-

Accelerated settlement expansion: Given the current government’s composition, we are likely to see a significant increase in settlement expansion activity, including possible moves to advance the so-called “doomsday” settlements such as E1/E2, east of Jerusalem, and Givat HaMatos, located between Bethlehem and East Jerusalem, both of which would sever north-south contiguity in the West Bank, thus making a future, viable Palestinian state impossible. At a minimum, we are likely to see an acceleration in plans for the encirclement of Jerusalem’s Old City as well as the retroactive legalization of dozens of settlement outposts, which are illegal even under Israeli law.

-

Forced evictions and demolitions: Israeli authorities may also seek to move ahead with planned forced evictions of Palestinian communities, most notably in East Jerusalem, where dozens of Palestinian families in the neighborhoods of Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan are facing court-ordered eviction, and in the southern West Bank community of Masafer Yatta. In parallel, we are likely to see an increase in targeted demolitions of Palestinian structures across the 60% of the West Bank classified as Area C, a long-standing demand of the settlers.

-

Loosening rules of engagement: National Security Minister Ben-Gvir has called for harsher measures against Palestinians, including a further loosening of the guidelines permitting the use of deadly force, or rules of engagement, by Israeli forces against Palestinians. In addition to producing even more deaths and injuries among Palestinians, including civilians, this would almost certainly lead to intensified friction, instability, and violence on all sides in the West Bank, East Jerusalem, Gaza, and even with Palestinian citizens of Israel.

-

Dismantling the Status Quo in Jerusalem: While Israeli extremists with help from the state have steadily eroded the Status Quo arrangement that has governed the holy sites since 1967, particularly in relation to the al-Aqsa Mosque compound, extremist cabinet ministers like Ben-Gvir could move to accelerate that process or do away with the status quo altogether, for example by allowing an expansion of Jewish prayer on the site. In particular, the growing size and frequency of visits by Jewish extremists to the site, such as the ones that took place during the Ramadan/Passover period in April, are seen as a major provocation and are likely to remain a potent source of violence and instability.

-

Possible de jure annexation: As de facto annexation through Israel’s settlement enterprise and policies of demographic reengineering continues apace in the West Bank and East Jerusalem, the threat of de jure annexation is increasing. Even in the absence of a formal declaration of annexation of some or all of the Occupied Territories, which would trigger immediate and overwhelming international opprobrium, more subtle forms of de jure annexation remain a distinct possibility. For example, the unprecedented decision by the Netanyahu government in late February to transfer certain authorities over the West Bank from the Israeli Ministry of Defense to Israeli civilian authorities is viewed by many legal scholars as a step toward de jure annexation.

-

Renewed/intensified violence in Gaza: Gaza, which has already seen four major wars in the last decade, remains on a knife’s edge and could erupt in violence once again at any moment, particularly if triggered by events in East Jerusalem or the West Bank. Israeli airstrikes on Gaza like those carried out in mid-May that killed several Islamic Jihad leaders as well as scores of civilians, including at least 10 children,77 is the type of escalatory spiral that is becoming all too common.

Any one of these developments alone could be enough to trigger an outbreak of sustained violence. Moreover, despite attempts by Israel to fragment Palestinians geographically, physically, and politically, events in one part of the Occupied Territories can and often do spill over to other areas. This was most evident in May 2021, during which violence in Jerusalem quickly spread to Gaza. That escalation in turn saw an unprecedented mobilization by Palestinians not just in the West Bank and other parts of the Occupied Territories, but also among Palestinian citizens of Israel — a moment that came to be known by Palestinians on both sides of the Green Line as the Unity Intifada.78

Tensions between Israel and the wider region

Israeli-Palestinian escalation is not likely to begin from the outside in. Netanyahu cherishes his past regional achievements, especially the Abraham Accords. His regional track record also includes maintaining strong bonds with the Egyptian president, reconciling with Turkey (albeit short-lived), negotiating indirectly (and unsuccessfully) with Lebanon, publicly visiting Oman, and secretly meeting with the Saudi Arabian crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman. He seeks to continue and build on these developments and has already stated his interest in pursuing normalization with additional countries, chief among them Saudi Arabia.

Regional leaders congratulated Netanyahu on his victory, including Jordan's King Abdullah, with whom Netanyahu had met in Amman in January, despite their previous disconnect, and Turkey’s President Erdoğan, with whom he has had problematic relations in the past. The UAE and Bahrain embraced Netanyahu in a warmer manner, and the UAE’s ambassador to Israel even met publicly with MKs Ben-Gvir and Smotrich.79 The UAE also hosted in January — as planned — the meeting of the Negev Forum working groups,80 but following Minister Ben-Gvir’s visit to the al-Aqsa Mosque compound/Temple Mount, it postponed Netanyahu’s visit to the UAE.

Israel-Arab relations did slow down afterward, with ministerial meetings between Israel and its neighbors becoming rare (and often taking place at multilateral events, rather than bilaterally), with a rising number of Arab condemnations of Israeli actions and the postponement of the Negev Forum’s ministerial summit. Practical cooperation between Israel and its neighbors, however, did continue, along with the implementation of previous understandings.

Moving forward, there are a number of potential points of friction, the first of which may be Jordan. Previously, King Abdullah had refused to communicate directly with Netanyahu since 2017 and did not trust him. The Lapid-Bennett government managed to mend ties with Amman, but a change in the status quo in Jerusalem, right-wing provocations around the al-Aqsa Mosque, or increased Jewish hostilities toward Palestinians will spark a negative reaction from Jordan that may be difficult to fix. The same might happen with Turkey, especially if there is an escalation in Jerusalem, even despite Erdoğan’s strategic decision to reconcile with Israel. The UAE and Bahrain are likely to be slower to respond to an escalation — in past instances, they issued statements of concern — and Egypt will assume its traditional mediator role, in coordination with international actors.

A significant Israeli-Palestinian escalation, if in the West Bank and not with radical Islamic factions in Gaza, is likely to lead to a harsh regional response. This will be manifested in official state reactions but also in likely expressions of negative public attitudes toward Israeli tourists in the region. Terror groups might also respond, attempting to target Israelis visiting or based in Arab or Muslim countries. Escalation might also negatively impact Israel’s ability to effectively participate in regional organizations, and will likely increase international criticism of Israel and attempts to pursue legal actions against its policies. The Israeli government, though, believes it can contain these developments and balance between its policies toward the Palestinians and its attempts to foster greater regional cooperation.

Possible Steps Toward De-escalation

While some sort of escalation, on at least one of the above fronts, may be unavoidable, the scope, as well as its negative consequences, can be managed and contained through preventive and proactive diplomacy. Conflict mitigation efforts can also play a key role here by helping to support pathways to de-escalation.

Preventive diplomacy

The risks of escalation are numerous and well known. This could be an advantage. In the past, rounds of terror or warfare often began suddenly, following an unanticipated event that brought negative underground currents to the forefront. The ability to anticipate escalation enables international actors to take preventive action.

For example, Jordan successfully carried out preventive measures in 2022, in the lead-up to Ramadan. Concern over possible friction in Jerusalem led King Abdullah to embark on a series of diplomatic missions81 that helped the month pass with relatively few incidents. Jordan can do that again, and it played an important role in holding the first of two regional security summits, in February, in Aqaba.

The impact of these recent security summits is mixed at best. Some analysts maintain that they helped reduce the chances for a wider escalation during the sensitive period of the month of Ramadan. But others see the summits as doing little more than helping Israel score a public relations victory and undercutting the credibility and legitimacy of the PA and President Abbas in the eyes of its people.

Turkey can also play a preventive role, especially regarding Gaza, given its normalization with Israel and relations with Hamas. These roles could be planned in advance, in coordination with the U.S., Egypt, and the U.N., which usually are the ones to contain escalations after they happen. An Israeli-Palestinian confrontation will endanger the national and regional interests of both Jordan and Turkey, so they may see benefit in playing a preventive role.

International actors can help set up mechanisms to contain regional spillover from an Israeli-Palestinian escalation. If such an escalation happens, Netanyahu will likely still be able to engage directly with the leaders of Egypt, the UAE, and Bahrain. That might be more difficult with Jordan and Turkey, which are highly sensitive to the Palestinian issue and whose leaders are no fans of Netanyahu. Bilateral mechanisms for strategic dialogue should be reinforced between Israel and both Jordan and Turkey now, before any potential escalation or its consequences spill over into those countries or the broader neighborhood. Such mechanisms should include government officials, not politicians, including the head of the National Security Council and the directors general of the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Defense. In times of crisis and disconnect between leaders, this mechanism will be a safeguard and may make the difference between containment and further escalation.

Again, the limited impact of these conflict-management measures in emergency security summits and the poor record of improving the security situation in a sustainable way must be kept in mind when considering the best pathways to a lasting de-escalation. The fact that recent summits did not produce lasting results or eliminate key tensions in relations is a sign of how limited de-escalation efforts will likely be without deeper efforts to address the roots of the conflict, including the power disparities between Israel’s government and the Palestinians.