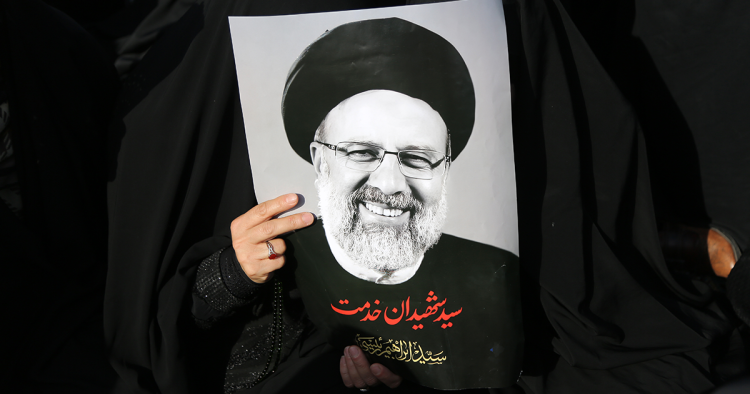

The death of President Ebrahim Raisi serves as a stark reminder of the pervasive instability within the Iranian system of government and its potential repercussions for the future of the Islamic Republic.

Following Raisi's death in a helicopter crash in late May, there have been widespread expressions of doubt about the circumstances around the incident on Persian-language media and social networks. Many of these discussions revolve around the possibility that Raisi was murdered. Although no reliable information has been published confirming this, many Iranians are clearly skeptical of the government narrative that it was an accident.

This skepticism is even common among staunch supporters of the Islamic Republic and those closely connected to the government — including, it seems, Raisi's own mother. Following the president’s death, a video emerged in which she vehemently curses "anyone other than God" who "killed" her son. Meanwhile, Iranian security agencies have been employing wide-ranging intimidation and suppression tactics against individuals who dare to challenge the official narrative about the president’s death.

The instability of the presidency

To understand why there is so much uncertainty and doubt about Raisi's death, one need look no further than the fate of previous heads of the executive branch over the Islamic Republic's 44-year history. With the notable exception of Ali Khamenei, who assumed the role of supreme leader in 1989, all other heads of the executive branch have either lost their government positions or their lives.

Mehdi Bazargan, who assumed the role of prime minister of the interim government following the 1979 revolution, is the first example of this trend. His disagreements with the ruling clergy led to his forced resignation in 1980, after which he remained in disfavor with the authorities until he died in 1995. Abolhassan Banisadr, Iran's first president, fled the country in 1981 to save his life and spent the rest of his days in exile, passing away in 2021. Mohammad-Ali Rajai, the next president, and Mohammad-Javad Bahonar, the next prime minister, were both assassinated in a bombing attributed to the Mojahedin-e-Khalq (MEK) organization in 1981. Mir Hossein Mousavi, who succeeded Bahonar as prime minister, frequently clashed with then-President Khamenei and was marginalized after the latter became supreme leader. Mousavi later ran for president in 2009; after accusing the government of electoral fraud over the results, which sparked the Green Movement protests, he has been under house arrest ever since.

With Khamenei's rise to supreme leader and the abolition of the role of prime minister in Iran’s constitution, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani became the first president of the new era in 1989. However, Rafsanjani's growing disagreements with Khamenei eventually led to his disqualification by the Guardian Council — a body aligned with the supreme leader that is responsible for vetting electoral candidates — from running in the 2013 presidential election. Rafsanjani drowned under suspicious circumstances in 2017, and his family believes he was murdered.

Subsequent presidents — Mohammad Khatami, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, and Hassan Rouhani — also had serious conflicts with the supreme leader and his appointees, especially during their second term. All three were sidelined after their presidencies, with their associates facing security pressure and accusations of antagonism toward the leadership and institutions of the Islamic Republic.

Khatami, who supported Mousavi in the 2009 elections, was effectively expelled from politics afterwards, to the extent that his image was banned from publication in official media outlets. Rouhani was barred by the Guardian Council from running in the 2024 elections for the Assembly of Experts, the body responsible for selecting the next supreme leader. Even Ahmadinejad, despite enjoying the supreme leader's full support during his first term and the early part of his second, was later disqualified from the 2017 and 2021 presidential elections.

Ahmadinejad's fate, in particular, fuels speculation that, despite Raisi's close ties to the supreme leader, there was no guarantee that he would have remained in favor until the conclusion of his second term had he survived. In the end, his time in office was cut short by his sudden death before his first four-year term was completed.

There is much speculation now about who will replace him. Nevertheless, whoever assumes the role next will inherit a position that has symbolized instability and misfortune for over four decades. This is particularly significant given the likelihood that the next president will be in office during the highly turbulent period between Khamenei’s death and the consolidation of power by his successor.

The fragile position of potential successors to the supreme leader

The symbolic significance of Raisi’s death becomes even more pronounced given his dual roles as both president and a longstanding potential successor to the supreme leader. Historically, in the Islamic Republic, candidates for leadership succession, much like heads of the executive branch, have either lost their government positions or died unexpectedly.

During Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s tenure as supreme leader, Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri emerged as the leading candidate to succeed him. In 1985, Montazeri was formally designated as Khomeini’s successor by the Assembly of Experts. However, following Montazeri's criticism of Khomeini over the 1988 mass executions of political prisoners, the then-supreme leader removed him from the role in early 1989, effectively eliminating him from political life.

Montazeri was not the only potential successor to Khomeini to be removed from the political sphere. Following the Islamic Revolution, at least three other influential clerics who were considered top candidates to succeed Khomeini met untimely ends. Morteza Motahari, the first head of the Revolutionary Council, was assassinated in spring 1979 by a rival fundamentalist group known as Furqan. Mahmoud Taleghani, the second head of the Revolutionary Council, died of a heart attack in the summer of 1979, with some of his family members suspecting foul play. Mohammad Beheshti, the secretary-general of the Islamic Republican Party, which was the leading political organization of the ruling clerics, was killed in a bombing attributed to the MEK in summer 1981.

Under Khamenei’s leadership, those considered top candidates to succeed him have similarly lost his confidence as well as their positions one after another. Rafsanjani, who played a crucial role in Khamenei’s rise to the leadership, was initially seen as a key successor but later experienced a sharp political decline.

After Rafsanjani, Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi, who served as the head of the judiciary in the late 1990s, emerged as a potential successor. Initially close to Ahmadinejad and his team, Shahroudi's status diminished in the late 2000s as Ahmadinejad's influence waned. Sadeq Larijani, the next head of the judiciary, was also seen as a likely successor. However, in the late 2010s, he became entangled in a power struggle with the then-head of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ (IRGC) intelligence organization, Hossein Taeb, who was close to Mojtaba Khamenei, Ayatollah Khamenei’s son. Following Larijani’s decline, Raisi and Mojtaba Khamenei were considered the main candidates to succeed the supreme leader. Now, Raisi, too, has been eliminated from Iran’s political scene.

Under the new circumstances, although Mojtaba Khamenei is the most prominent potential candidate for the leadership succession, he is not the only contender. For example, in recent years, Alireza Arafi, the influential head of Iran's seminaries, has also been mentioned as a potential successor. Additionally, it is likely that other individuals will be added to the list of leadership candidates in the future.

Regardless of how likely the current or new candidates are to succeed, it cannot be assumed that they will retain their positions indefinitely. Even if they do not lose the supreme leader's trust, there is no guarantee they will not die before him or be eliminated from the running for other reasons.

All of this suggests that, depending on how long the supreme leader lives, the final list of potential candidates is subject to various changes that may be entirely unexpected.

Uncertain transition in the absence of heavyweight actors

Moving forward, uncertainty over the Islamic Republic’s endurance as a political system continues to loom large. Nevertheless, even setting aside the prospect of potential regime change, the death of Raisi, as both president and a leading candidate for the role of supreme leader, accentuates the inherent instability within Iran's highest echelons of power.

So far, both the presidency and the supreme leadership have been regarded as the domains of the regime's most prominent figures. Yet nearly all presidents and leadership succession candidates have either been removed from power or have died. In other words, almost none of these prominent figures is currently positioned to play a significant role in the highly sensitive period after Khamenei’s death.

As influential clerics once seen as potential successors continue to be sidelined or eliminated, and with the overall decline in the clergy's stature in Iran, it is anticipated that a markedly less influential figure will assume power after Khamenei. In such a scenario, the IRGC — as Iran's strongest military, security, and economic actor — will undoubtedly play a central role in shaping the country’s power dynamics.

In recent years, even the few effective military commanders with the potential to unite the Islamic Republic’s disparate governing factions have also met with untimely ends. The most prominent instance of this was Qassem Soleimani, the commander of the IRGC Quds Force, who was killed by the US military in a drone strike in Baghdad in early 2020. Soleimani was highly influential across various factions of the Iranian regime and was possibly the most popular official in the Islamic Republic — although the bar is not very high as most officials are generally unpopular. His position in the IRGC was unlike that of any other commander. The handful of military figures that are well known often owe their renown to political maneuvering, management controversies, or economic scandals, rather than their military performance or wartime experience.

Without influential figures from various backgrounds to help manage the transition, it appears increasingly likely that the potential for instability within the Iranian government will markedly escalate after Khamenei. This scenario will unavoidably expose the Islamic Republic to unprecedented risks that could imperil its very existence.

Nevertheless, this does not necessarily mean that the end of the Khamenei era will lead to the fall of the Iranian regime or usher in fundamental change. Broader changes are only likely to occur if, through a combination of internal and external factors, the vacuum created by Ayatollah Khamenei’s death can be effectively leveraged to drive a comprehensive effort to bring them about.

In the absence of a force powerful enough to drive such a transformation, the Iranian regime may even survive highly unstable conditions following the death of the supreme leader. In turn, it is possible that a weaker successor will ultimately emerge to take on the leadership of a different type of Islamic Republic: a political regime that is weakened, with the military playing a more prominent role than ever, but one that nonetheless continues to survive.

Marie Abdi is an Iranian political researcher focusing on the Islamic Republic's domestic and regional strategies.

Photo by Fatemeh Bahrami/Anadolu via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.