Iran’s new president, Ebrahim Raisi, has presented his first draft budget bill for the upcoming Iranian year (1401), which starts on March 21, 2022. Rather than facilitating a much-needed economic recovery, the proposed budget is designed to strengthen the regime’s power base and impose austerity while keeping society under control. Although Raisi still claims that his administration will not tie the fate of the country’s economy and people’s wellbeing to foreign sanctions and ongoing negotiations over the revival of the 2015 Iran nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the details of the proposed budget cast doubt over how the administration will fulfill its promises for economic growth otherwise. If the conditions for an economic recovery do not materialize, Iran will prioritize regime security and countering future popular uprisings through budget allocations aimed at shoring up the Islamic Republic’s “trinity” of security-military, propagandistic, and commercial-clerical apparatuses.

What does the proposed budget entail?

The total national budget amounts to about €116 billion (IRR 36,310 trillion), i.e. €24 billion or 26% more than the current budget for Iranian year 1400. This breaks down into two parts, the proposed general government budget (Budget-e Omoumi-e Dolat), which is usually considered as the government’s fiscal policy and accounts for about 41% of the total, and the budget allocated for so-called “public enterprise,” which includes all public companies, banks, and institutions and accounts for the remainder.[1] Compared to the current year, the general government budget is set to increase by 9.57% and that of public enterprise by 29%.

In addition, the proposed budget assumes an overly ambitious GDP growth rate, given that growth in the current Iranian year was just 1.5%. “We have targeted 8% economic growth and we should have a national review of the 1401 budget. We are considering this growth rate and everyone should try to reach this level,” President Raisi told the parliament.

In fact, the proposed budget appears to be a contractionary one. In times of economic crisis, governments usually implement expansionary fiscal policies by increasing their expenditure in real terms to help support a recovery. Given the expected inflation rate of around 40% next year when adaptive expectations are considered, a less than 10% increase in the general government budget in nominal terms means that it will shrink by about 22% in real terms, likely leading to an economic slowdown. Since governmental revenues are unlikely to increase (as we discuss below), Raisi claims that the contractionary budget is aimed at controlling high inflation, which mostly affects the poorest in society. This is based on the fact that in Iran’s closed economy a budget deficit is usually financed through borrowing from the central bank, which then paves the way for higher inflation.

Revenue expectations: Overly optimistic

The new budget is expected to be financed through, among other sources, 9% higher revenues from oil exports and a 62% increase in tax receipts compared to the current year. For the current fiscal year, oil exports were estimated to reach 2.3 million barrel per day (bpd), although other sources have put this figure much lower, at a maximum of 700,000 bpd, with a barrel worth between $40 and $60. For the next year, the Raisi administration has targeted exports of 1.2 million bpd with an estimated price of $60 per barrel.[2] Therefore, the reason the budget would achieve a much larger revenue in nominal national currency terms is that the government may use a higher exchange rate to convert oil proceeds to national currency. We should also bear in mind the discount Iran offers its main oil customer, China, which is unlikely to change in the event of sanctions relief given Tehran’s long-term policy of courting Beijing. According to a November 2021 Reuters report, in the previous quarter Iran had exported 15 million barrels of oil per month to China, offering it a discount of $5-6 per barrel, which amounts to a monthly discount of $90 million. As Tejarat News noted, when extrapolated out over an entire year, this would equal 10 months of cash-subsidy payments to Iran’s entire population.

According to the proposed draft, tax revenue (including from higher import tariffs) will also increase by a massive 62%, which would mean putting more pressure on the marginalized private sector and ordinary people, who are already suffering from the economic crisis. To achieve this ambitious target, the government has said its goal is to identify tax evaders and get them to pay up. Former President Hassan Rouhani said the same thing a number of times, but in the end didn’t go after tax-exempt semi-public entities like foundations (bonyâds), which are seen as politically untouchable.

A contractionary budget impeding future recovery

Given the high rate of inflation and the limited increase in the proposed general government budget, the Iranian government’s fiscal policy is likely to prove contractionary. First, this is because the government will increase the salaries of public employees and pensioners by only 10%, which will exacerbate discontent as real wages and buying power shrink. Second, such a fiscal policy will impede recovery in the next year. Therefore, to achieve the promised 8% growth rate, other components of aggregate demand (i.e. consumption, investment, and net exports) should increase to compensate for the reduction in government expenditure. As real wages are pushed down, however, consumption will not grow. Nor is investment likely to rise, as the Raisi administration has not been pursuing a policy that will increase either domestic or foreign direct investment. As long as the specter of intensifying U.S.-Iran tensions looms and sanctions persist, poor business sentiment and a large risk premium will remain major barriers to investment. In addition, sanctions and Iran’s inclusion on the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) blacklist will also hamper efforts to increase net exports. Taken together, all of this indicates that the promised growth rate is, despite the administration’s claims to the contrary, de facto tied to the removal of U.S. sanctions, which in turn hinges upon the success of the negotiations to revive the JCPOA. A success in the Vienna talks could lead to a surge in oil revenues that would enable the government to reduce its budgetary dependency on the central bank through borrowing. This will allow for greater control of inflation next year, as was the case after the implementation of the JCPOA in 2016.

Cementing the regime’s “trinity” with 7% of the total national budget

The proposed budget has fueled heated debates, especially on social media, because it allocates massive funding for the Islamic Republic’s “trinity”: the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB), and religious organizations. Pedram Soltani, a Tehran-based entrepreneur and philanthropist, tweeted that the 1401 budget forces people and private companies to pay more taxes to strengthen those organizations that help officials take and keep office, effectively referring to the above-mentioned “trinity.”

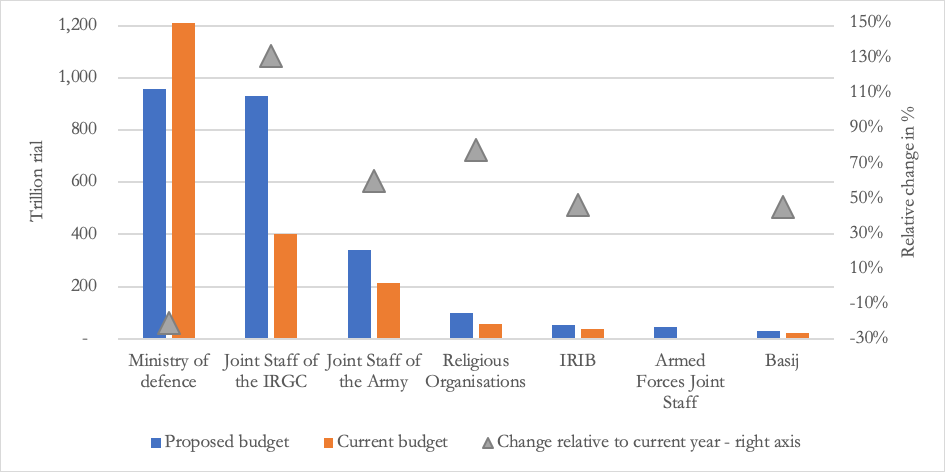

The IRGC is the clear winner in the new proposed budget, with a 131% increase over the current Iranian year (IRR 930,000 billion or almost €3 billion).[3] This is a continuation of an existing trend: During Rouhani’s presidency, the IRGC’s allocations were already rising in budgets centered on austerity and security, with 58% more funds allocated to the IRGC in the current budget than in the previous one. Also part of Iran’s military-security apparatus are the Basij paramilitary organization (Sâzmân-e Basij, IRR 30,830 billion, a 45% increase compared to the current budget), which is under the IRGC’s control; the Ministry of Defense with an allocated budget of IRR 955,000 billion (a 21% reduction); the Joint Staff of the Islamic Republic of Iran Army (i.e. the regular army or Artesh) with an allocated IRR 340,000 billion (a 60% increase); and the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Islamic Republic of Iran with IRR 46,000 billion (a massive 977% increase). In sum, the entire military-security apparatus has received a more than 24% rise, which is in real terms less than the current year given the inflation rate. In other words, with the structural reform introduced in the national budget, Raisi has massively strengthened the IRGC to the detriment of the Ministry of Defense.

Figure 1: Proposed budget allocations for upcoming Iranian year 1401 for the Islamic Republic’s “trinity” relative to the current year

Source: Islamic Consultative Assembly (Iran’s Parliament) and Tabnak (“Budget changes of religious institutions in the 1401 budget,” Dec. 14, 2021.

Public broadcaster IRIB is another key beneficiary, seeing its budget rise by 46% to IRR 52,892 billion (i.e. almost €169 million). IRIB, whose domestic programs have long been notoriously unattractive to Iranians and marginalized by the popularity of Western-based Persian-language channels, also offers foreign-language channels that aim to serve as a tool of “soft power” for the Islamic Republic by disseminating its views.

Religious organizations saw a dramatic rise in their budget allocations as well. The largest recipients are the Seminaries Services Center (Markaz-e Khadamât-e Hozehâye Elmieh, IRR 28,080 billion, +180%), whose allocation is greater than that of the Department of Environment and government bodies such as the Crisis Management Headquarters, while it also receives funding from the Office of the Supreme Leader (Beyt), a quasi-parallel government; the Islamic Propagation Organization (Sâzman-e Tabliqât-e Eslâmi, IRR 7,418 billion, +76%); and the Waqf and Endowments Organization (Sazmân-e Oqâf va Omour-e Kheyrieh, IRR 6,980 billion, +67%).

A budget for stormy times ahead?

This is not the first time that this “trinity” has received a large part of the budget. Indeed, regime security interests have always played a major role in allocating budgets in the Islamic Republic. This time around, cementing this “trinity” is even important to Tehran’s leadership as the security threats against the Islamic Republic have intensified in recent years.

First, the IRGC remains the regime’s primary instrument to protect its survival and interests, both internally and externally. Its 131% budgetary increase signals that Tehran wants to cement the IRGC’s role as the linchpin for the Islamic Republic to expand its security and economic footprints.[4] As Iran’s economic crisis deepens, the security challenges facing the regime are likely to intensify as well. The expected poor economic recovery and reduction in real wages in the next Iranian year will increase discontent and may trigger large-scale protests. As the main beneficiary of the Raisi administration’s proposed budget, the IRGC will be well-financed and prepared to crush protests that could spiral into nationwide uprisings, as seen in 2018 and 2019. Second, amid mounting internal and external security threats, Iranian officials need to control narratives that challenge their rule, to justify their behavior and win over public opinion. It is therefore likely that the IRIB’s budget will be further expanded to achieve regime stabilization. Finally, religious institutions are in charge of educating a new generation of pro-regime clerics and engaging in politico-religious propaganda. These organizations, along with their administrators, staff, and students, are an essential part of the ideological machinery of the Islamic Republic.

By shoring up all three of these pillars, Tehran wants to prepare for more stormy times ahead, yet its reliance on repression and propaganda while potentially exaggerating future income may exacerbate the nation’s ills instead of helping to cure them. The jump in oil income that the proposed budget relies on may only be realized if a deal is reached in Vienna to revive the JCPOA. In other words, Raisi’s claim that the fate of Iran’s economy is not tied to sanctions and the JCPOA’s future is not only utterly misleading, but it is also contradicted by his administration’s own budget assumptions.

Dr. Ali Fathollah-Nejad is an Associate Fellow at the Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy & International Affairs (IFI) at American University of Beirut (AUB), the author of Iran in an Emerging New World Order: From Ahmadinejad to Rouhani, and the Initiator and Co-Host of the Berlin Mideast Podcast (Konrad Adenauer Foundation). You can follow him on Twitter.

Dr. Mahdi Ghodsi is an economist at the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies and an Adjunct Professor at Vienna University of Economics and Business. His research focuses on international trade, international trade policy, non-tariff measures, industrial policy, foreign direct investment, global value chains, political economy of sanctions, and the Iranian economy. You can follow him on Twitter. The views expressed in this piece are their own.

Photo by Meghdad Madadi/ATPImages/Getty Images

Endnotes

[1] As Iran’s Supreme Audit Court has recently reported, the realized budget of the ‘public enterprise’ in the last fiscal year (ending on March 20, 2021) amounts to IRR 24,672 trillion (i.e. 70% of the GDP), which was 80% larger than legislated, and even larger than the proposed budget of the “public enterprise” for the next year (i.e. IRR 22,314 trillion).

[2] This is calculated with a barrel worth $60 and a U.S. dollar equaling IRR 155,000. If one dollar equals IRR 310,000, then, 620,000 bpd should be exported to realize the proposed revenue. Therefore, the government is free to choose how to sell the dollar revenue of the exported oil in the domestic exchange market.

[3] The planned increase for the Iranian calendar year 1401 is about 130%, which would be a 230% rise compared to the 1399 budget: ((929-402)/402)*100=131

[4] Although in this article, we do not account for the budget allocations for the IRGC’s economic empire.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.