This essay is part of the Middle East-Asia Project (MAP) series on “'Civilianizing' the State in the Middle East and Asia Pacific Regions.” The series explores the past and ongoing processes of Security Sector Reform (SSR) in Asia-Pacific countries and examines the steps already taken and still needed in the MENA region. See More …

Police reform has lagged in Tunisia’s transition. Police violence, police impunity and a national sense of insecurity remain substantial concerns. The problems facing the Tunisian economy have drawn attention away from police reform, which had seen some positive change in 2011-2012. Since then, police unions have managed to stymie the reform process and have insulated the police from change. In addition, although the potency of the securitization argument (i.e., the police must be freed from civilian “interference” in order to fight terrorism) has waned, it remains a significant obstacle to reform. Challenging this argument and transforming the relationship between the police and the people requires expanding platforms for discussing day-to-day local security issues.

Violence, Impunity and National Insecurity

Eight years after the revolution, the transformation of the police in Tunisia still has distance to make. The clashes that occur at regular intervals between police and protesters expose an ineffective public order capability[1] and reflect a troubled relationship between the police and the population.[2]

Police violence also remains a major issue in terms of mistreatment during investigations.[3] What is more, police impunity (i.e., its record of getting away with crimes against civilians) is also plainly evident. The most recent high-profile example of such impunity took place in February 2018, when police officers raided a court in Ben Arous to free five of their colleagues on trial for torture.[4] This astonishing operation was part of a series of similar stunts where officers have obstructed the course of justice to protect their own.

On the national level, feelings of insecurity among the police and the broader population are considerable and are undermining confidence in the police’s ability to protect the state and the people from various dangers, ranging from the banal to the existential. A curious manifestation of this sense of multi-layered vulnerability arose in May of last year, when Transtu, the Tunisian railway network, was reported[5] to be planning the creation of its own security force, citing both vandalism on its rolling stock and terrorist activity in areas lacking police presence.

The impact of terrorism on Tunisia has grown since the Revolution. Deaths from terrorism in Tunisia increased five-fold between 2011 and 2016,[6] and with the territorial defeat of ISIS, there is a fear of and anger at[7] a bitter reflux westwards in the form of the return of Tunisians who have gone to fight for Daesh, HTS and other groups in Syria and Iraq.[8] In an Arab Barometer survey of 2016, 97% of respondents were very worried about the possibility of a terrorist attack in the context of going about their daily lives.

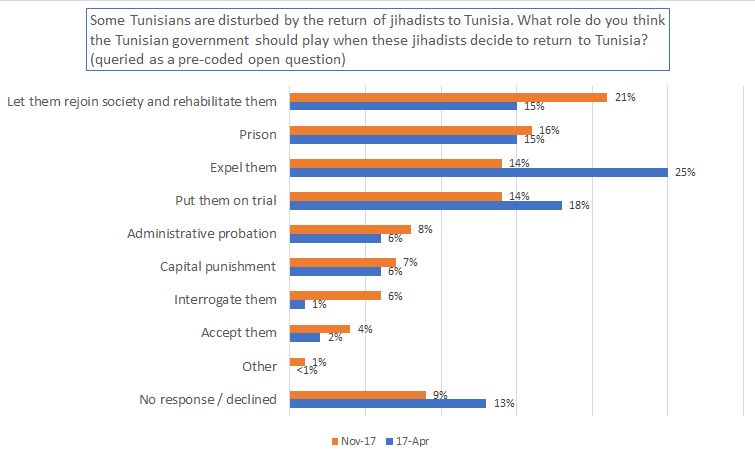

Figure 1. What to Do with Returning Jihadists

Source: Center for Insights in Survey Research (December 2018): 124. [Translated from the original French.]

Figure 2. MENA GTI Rank / Change in Score, 2002-2016

Note: In terms of terrorist impact, Tunisia has a middling score in the MENA region.

Source: Global Terrorism Index: Measuring and understanding the impact of terrorism, 2017.

With this situation in mind, clearly the police’s transition from its role as a force protecting the Ben Ali regime to a fair and effective service protecting the rights of all Tunisians, working on a cooperative basis with the people, is far from complete. This will become even clearer as 2019 progresses towards both parliamentary and presidential elections, when the intensification of street politics will mean an increase in police-protester clashes and violence.

So, what has happened to the security sector in the most promising of the Arab Spring nations, and how might positive change be restarted or accelerated?

The Trajectory of Police Reform in Tunisia

Police reform — or something more vigorous — was certainly in the minds of Tunisia’s revolutionaries in 2011. The police were a major target of the demonstrators, and hundreds of police stations were torched. The police were understood by revolutionaries as both a symbol and a tool of the Ben Ali regime.

Initially after the uprising, police reform progressed well, even if in a haphazard manner. In 2011, the so-called “Political Police” (State Security Directorate) was dissolved, and 11 security directors were dismissed. The legally ambiguous ways in which both reforms were achieved was a sign of the revolutionary momentum and its haste for change in policing.[9] In addition, a human rights guide for the police was crafted between the Ministry of Interior and UNHCR. The 2014 Constitution specified the political neutrality of the police and the armed forces but importantly gave insufficient guarantee of civilian oversight of the police. Since then, little progress has been made in terms of restructuring the police, further legislative protection of rights, or improving civilian oversight.

Economic Urgency, Police Unions and a Securitization Discourse

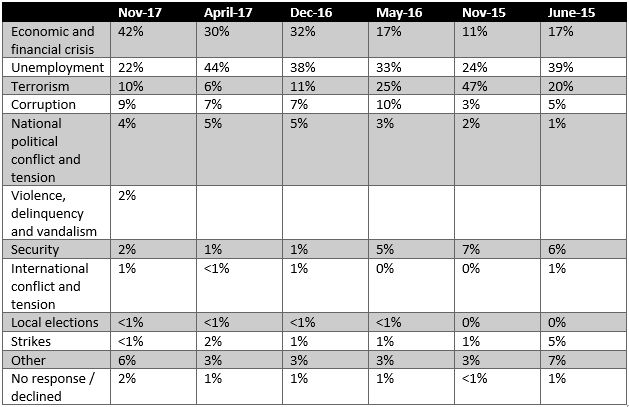

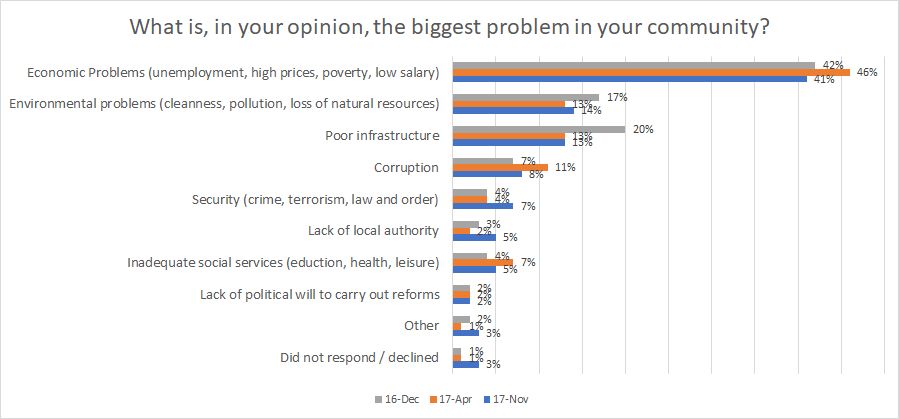

There is an important political economy explanation to the lack of progress. Focus on the nation’s economic performance and how to rescue it has taken up much of the country’s political energy and has drawn focus away from security sector reform. Numerous surveys reflect Tunisians prioritization of economic concerns over security issues both at the national level (see Figure 3) and the local level (see Figure 4), and where decisions are framed as a tradeoff between economic reform and security reform, a 2017 study suggests that Tunisians will choose the former.[10]

Figure 3. Tunisian Citizen Concerns Rated

Source: Center for Insights in Survey Research (November 2017): 5. [Translated from the original French.]

Figure 4. Tunisian Citizens Rank Top Problems in Local Community

Source: Center for Insights in Survey Research (November 2017): 6. [Translated from the original French.]

While economic priorities have drawn focus away from other areas of reform, there have nonetheless been attempts at changing the police for the better. A prime actor obstructing these attempts has been the police unions. Since the Internal Security Forces Statute of 2011, over one hundred police unions, large and small, have formed in Tunisia.[11] These unions have been active in pushing for better working conditions; they are very diverse in character and ambitions, and some have politicized and blocked change where they perceive it to be threatening.

For instance, not only have police unions been behind several ‘rescue’ operations of police officers on trial, they have also been effective in blocking both high-profile transitional justice cases and structural reform of the security sector. For example, in 2012, a police union blocked the removal of a security director charged with killing protesters.[12]

Projecting political power through strikes, disrupting interior ministers’ reform policies and exercising influence over the choice of minister made the police unions an intimidating grouping, and rendered the security services an unattractive target for reform from the point of view of politicians.

Police unions have argued for the independence of the police from the civilian administration on the grounds of national security, especially regarding the threat of terrorism. This “securitization” argument or discourse made the case for “leaving the security forces be” on the basis that police must be freed from the politicking of inept political parties in order to stabilize the country and meet the threat of terrorism.[13] Police unions have taken this argument to an extreme at certain points by arguing that challenges to police impunity represent support for terrorism. This tactic was evident in August 2014 at the police union protest at a Kasserine courthouse’s sentencing of a police officer for murder, where the unions equated the sentence with support for terrorism.

Probably the most dangerous development were the attempts up to 2017 at passing the Prosecution of the Abuses Against the Armed Forces Law, which among other deleterious effects, would have strengthened police impunity.[14] Overall, these developments since 2011 have led some observers to chart the “autonomization” of the Tunisian police,[15] or to identify it as a “rogue” force[16] that the unions have made independent of civilian oversight, and therefore successfully immunized to change.

Where next?

The blockers to change in Tunisian police seem likely to persist. Economic prospects continue to be uncertain and the economy will remain the greatest priority for Tunisians.[17] And, even if it may be that the apogee of the police unions’ power has passed,[18] the securitization discourse will remain a significant impediment to change.

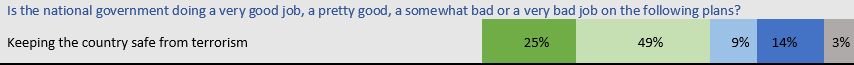

Likewise, while there is a pervasive fear of terrorism and a significant lack of confidence in the police, a majority of the public yet believe that the police are doing a good or a very job fighting terrorism (see Figure 5) and meanwhile have little confidence in political parties. This makes it seem likely that the public will continue to be happy with the bargain of so called "security" at the price of police reform.

Figure 5. Tunisians Rate Government Performance

Source: Center for Insights in Survey Research (November 2017): 26. [Translated from the original French.]

Finally, from a conceptual viewpoint, it is also doubtful whether there is a widespread understanding of police reform being anything more than capability building, rather than wholesale transformation towards a rights-based policing service.[19]

The Power of the Local Negotiation and Changing the Conversation

With these prevailing trends, it is difficult to see how police reform efforts can take the limelight, and even if they do so, how they might circumvent institutional resistance and the prevailing securitization discourse. Tunisians are not exactly happy with the police, but for now it seems that they are also not that interested in changing them.

Part of the answer to this dilemma lies in the power of everyday security concerns at the local level to unpick the securitization argument. The argument frames security concerns primarily at the national level, and often at close to the existential threshold. However, when space is made at the local level for citizens to express their concerns, there emerges a different framing of security. For example, local consultation by an NGO in areas including Kasserine and Ben Guerdane revealed concerns with drug abuse and road safety around schools, as well as the manifestations of hot strategic issues, such as violence around football stadiums and radicalization.

This consultation was carried out as part of a community security project in a cooperation between Al-Kawakibi Democracy Transition Center and Search for Common Ground.[20] The project supports the formation of local security committees to liaise with the police and bring local issues into the conversation about security. The project efforts were publicized by an extensive media campaign to raise awareness of the possibility and positivity of this type of relationship.

Such efforts are important for two reasons. Firstly, they support a more conciliatory and cooperative relationship between the police and communities. Ordinary Tunisians involved in the projects reported that the idea of working with the police in a cooperative manner was inconceivable before their involvement and before the creation of new relationships with the local police officers.

Secondly, they can help to deflate the securitization discourse. These conversations bring into focus the effectiveness of the police’s policies and procedures to meet local concerns, which also have strong resonance with police officers themselves.

With such a dynamic in mind, a Community Policing initiative has been set up in a dozen police stations in an initiative funded by UNDP. The measure of its success will be the extent to which the police takes on board the views of the community security committees.

Expanding the Conversation

These projects are, of course, limited in many ways. Geographically, they only cover a dozen or so police jurisdictions. As importantly, forming local security committees does not mean that the communities’ priorities are actually taken up by the police and transformed into local policing policy. For this to happen, there must be motivation from within the communities, as well as motivation and enabling from above. Police officers need both to be allowed to change the way they work and to be rewarded for doing so.

Generating such momentum for top-down change starts with amplifying the local conversation about security by expanding the reach of such projects. Increasing the number of people involved in working constructively with the police and ensuring media attention will place greater focus on the how the police must change and will bring a greater subtlety to the discourse.

This national conversation will take years to have an effect and in terms of donor strategies cannot be considered the only tool in the box. In the meantime, police violence will continue to be a deadly problem, especially around public order. However, without serious support to a national discussion regarding the role of the police, the necessary transformation will simply not occur, and Tunisian security sector reform will remain blocked.

[1] “Public order capability” refers to the ability of the police to protect life, property and the law in situations where large crowds amass (e.g., demonstrations and sports matches).

[2] In a 2018 survey, 74% of respondents stated that they had “little” or “no confidence” in the police. This rate compares closely to confidence in Parliament and is not unusual in terms of public perceptions of state organs. See Middle East Opinion, Zogby Research Services (2018):10.

[3] L’Organisation mondiale contre la torture claims that patterns of torture under the Ben Ali regime have persisted until today. According to its 2017 report, 34 individuals became torture victims in police stations. Maryline Dumas, “En Tunisie aujourd’hui, on torture encore comme sous Ben Ali’,” Middle East Eye, February 15, 2018 https://www.middleeasteye.net/

[4] Sharan Grewal, “Time to Rein in Tunisia’s Police Unions,” Project on Middle East Democracy (POMED), March 2018, https://scholar.princeton.edu/sites/default/files/grewal/files/grewal_f….

[5] “La Transu veut créer sa police: Mais que fait le ministère de l’Intérieur,” Kapitalis, May 23, 2018, http://kapitalis.com/tunisie/2018/05/23/la-transtu-veut-creer-sa-police….

[6] According to The Global Terrorism Index, there were four deaths due to terrorism in 2011, and twenty-two in 2016, while 81 deaths in 2015 was the highest figure for the period. Global Terrorism Index 2017, Institute for Economics & Peace (2017): 39.

[7] “Tunisie: des manifestations contre le retour des djihadistes,” Le Point, January 8, 2017, https://www.lepoint.fr/monde/tunisie-des-manifestations-contre-le-retour-des-djihadistes-08-01-2017-2095488_24.php.

[8] Infamously, Tunisia ranks first international site of origin for foreign fighters in ISIS, both in absolute (c.6,000 individuals) and per capita terms (c. 520 individuals per million people). “Foreign Fighters: An Updated Assessment of the Flow of Foreign Fighters into Syria and Iraq,” The Soufan Group, December 2015, https://wb-iisg.com/wp-content/uploads/bp-attachments/4826/TSG_ForeignFightersUpflow.pdf. Tunisians are divided over the correct way to deal with returnees (see Figure 1). For a detailed treatment of (de-)radicalization of Tunisians, see Emna Ben Mustapha Ben Arab, “Radicalization in Tunisia: In Search of a Civilian Approach,” in Lorenzo Vidino (ed.), De-radicalization in the Mediterranean: Comparing Challenges and Approaches (Milan: ISPI, 2018): 93-105, https://www.ispionline.it/sites/default/files/pubblicazioni/mediterraneo_def_web.pdf.

[9] Haykel Ben Mahfoudh, “Security Sector Reform in Tunisia Three Years into the Democratic Transition,” Arab Reform Initiative, 2014.

[10] Nicholas Lotito, “Security Reform during Democratic Transitions: Experimental Evidence from Tunisia,” SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, August 24, 2017.

[11] A number of the unions were formed before legislation allowed it and were retrospectively legalized. Wijdan al-Miqrani, Dawr al-niqabat fi islah al-manzumah al-amaniyyah fi tunis, Arab Reform Initiative (February 2016): 2.

[12] A useful critique of the activities of the unions can be found in Sharan Grewal, “Time to Rein in Tunisia’s Police Unions,” Project on Middle East Democracy, March 2018.

[13] Police unions are also engaged in advocating for improved police conditions. The unions do not enjoy universal support among police officers, some of whom are critical of how much the unions are asking for and of their politicized activities.

[14] Amna Guellali, “Draft Law Could Return Tunisia to a Police State: Parliament Should Reject Abusive Security Bill,” Human Rights Watch, July 24, 2017, https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/07/24/draft-law-could-return-tunisia-police-state.

[15] Moncef Kartas, “Foreign Aid and Security Sector Reform in Tunisia: Resistance and Autonomy of the Security Forces,” Mediterranean Politics 19, 3 (2014): 374, 382–383.

[16] Yezid Sayigh, “Dilemmas of Police Reform: Policing in Arab Transition,” Carnegie Middle East Center, 2016.

[17] Jihen Laghmari and Samer Al-Atrush, “Arab Spring’s Lone Democracy Teeters as Economy Refuses to Heal,” Bloomberg, February 5, 2019, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-02-06/arab-spring-s-lone-d….

[18] In 2014, the law was amended to allow police officers and soldiers to vote in municipal and regional elections. However, the low turnout of police officers in the 2018 municipal elections suggests a loss of political momentum for the police unions.

[19] Lotito, “Security Reform during Democratic Transitions,” 21.

[20] See Search for Common Ground, “Security Sector reform in Tunisia,” https://www.sfcg.org/tunisia-security-sector-reform-ssr-project/.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.