Summary

Egypt is not alone in having been knocked into a pit by the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, but it will have to dig itself out on its own. However, if Egypt is going to do so, it needs to rethink its approach to development, starting with looking for the silver lining to the pandemic. Is it possible to address existing issues that have been brought home by the exceptional circumstances? In this report, contributors dissect the weaknesses that make Egypt particularly vulnerable to external threats and examine ways in which to address these vulnerabilities and shore up the economy and the business and developmental environment.

Contents

1. Introduction: Evolution, Adaptation, and Survival

Mirette F. Mabrouk

2. COVID-19 in Egypt: The Return of Harsh Realities

Samer Atallah

3. Does Digital Transformation Present an Opportunity for Egypt to Autocorrect?

Sherif Kamel

4. As Egypt Recovers, Sustainable Growth Must Remain at the Heart of its Development Plans

Sarah El Battouty

5. Opportunity Amid Adversity: COVID-19 Could Pave the Way for Closer Egypt-China Economic Ties

Deborah Lehr

6. Egypt and COVID-19: The Day After

Yasser Elnaggar

7. The Silver Lining of COVID-19: Institutional Reform to the Rescue of the Egyptian Economy

Abla Abdel-Latif

Introduction: Evolution, Adaptation, and Survival

Mirette F. Mabrouk

Egypt is not alone in having been knocked into a pit by the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, but it will have to dig itself out on its own.

Right before the pandemic started shuttering businesses and wreaking havoc globally with health and livelihood, Egypt’s economy was seeing the fruits of a comprehensive economic reform program backed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) via a $12 billion loan in 2016, through the Extended Fund Facility program. Three years later, the economy was growing at an impressive clip — 5.6 percent. The budget deficit continued to fall, reaching 7.8 percent of GDP right before the pandemic hit.1 Foreign reserves were up, remittances totaled $26.8 billion, tourism revenues tipped an all-time high of $13 billion, and the Suez Canal poured $5.9 billion into the national coffers. Long considered an attractive emerging economy market, Egypt was again rated the most attractive country for foreign direct investment in Africa in 2019.2

These impressive macroeconomic gains, however, came at a heavy price for ordinary Egyptians. An IMF-mandated devaluation of the Egyptian pound meant that people woke up to prices that had doubled or tripled, as well as slashed fuel subsidies, in an effort to bring down budget levels, leading to soaring prices on almost any product one could care to name. Along with the introduction of a value-added tax (VAT), these measures all drove up the inflation rate to unprecedented heights before it could be wrestled down to a more manageable level.

By April, it was clear that those parts of the economy that had boosted Egypt’s performance had become a liability. Remittances, tourism, and even Suez Canal revenues are vulnerable to global market trends. The tourism business was losing over $1 billion a month at the height of the fallout and remittances were at risk due to increasing economic pressure on Gulf countries, where almost 4.5 million Egyptians are employed. Unemployment, which had fallen to 7.7 percent by the beginning of the year, started steadily inching its way back up thanks to the trade slump in general and lockdowns in particular and is expected to climb to 11.6 percent by 2021.

Egypt’s informal economy has been especially hard hit. This sector absorbs almost 50 percent of all non-agricultural employment and accounts for 30-40 percent of the country’s economy. This sector tends to react to socioeconomic changes, often favorably. It propped up its formal counterpart following the strain during the 1990s reform program, again after the global economic crisis of 2008, and once more after the Arab Uprisings of 2011. More flexible than its formal counterpart and less encumbered by bureaucratic restrictions, it managed to absorb almost 1.6 million workers during those two last crises. However, that flexibility comes at a cost: The lockdowns crippled the sector and the lack of any insurance meant that workers had to put in longer hours for diminishing returns and are extremely vulnerable to external threats.

To its credit, the government moved fast to try to counteract the fallout from the epidemic. Among other measures, the Central Bank slashed interest rates by three percentage points, removed ATM withdrawal fees for six months, exempted non-performing loans and late payments from fines, and told banks to provide credit lines for companies to finance salaries and capital. Additionally, the cash cover exclusion period for some foodstuff was extended for 12 months. The tourism industry, which employs about a tenth of the population, has come in for special support, on both the employer side, in the form of two-year credit facilities, and the employee side, in the form of a decree forbidding the dismissal of any employees during the crisis.

The fallout from the pandemic meant that the government, which had previously announced that it would only be looking to the IMF for technical advice but no loans, had to retrace its steps. In June 2020, the IMF approved an unconditional loan of $2.77 billion under the Rapid Financing Instrument program,3 and another $5.2 billion loan under the Stand-By Arrangement framework.4

However, if Egypt is going to dig itself out of this hole, it needs to rethink its approach to development, starting with looking for the silver lining to the pandemic. Is it possible to address existing issues that have been brought home by the exceptional circumstances?

In this report, several contributors dissect the weaknesses that make Egypt particularly vulnerable to external threats and examine ways in which to address these vulnerabilities and shore up the economy and the business and developmental environment.

Samer Atallah dissects how the Egyptian economy’s reliance on tourism, remittances, and the Suez Canal makes it so vulnerable to external shocks. Non-oil exports have not expanded beyond traditional markets and still operate within very weak value chains, the limits and vulnerabilities of which were exposed by the pandemic. Foreign investment is still confined within the areas of portfolio investment in government debt instruments. He targets social safety nets, the provision of equitable health care services, and the improvement of job creation mechanisms as essential fixes.

Sherif Kamel explores how Egypt might have an opportunity to autocorrect via a digital transformation. The technical and digital opportunities offered mean that Egypt can change its mindset to become growth oriented, agile, and aggressively competitive. Among other options, he suggests digitization could offer a seamless customs and tax processes platform that can remove the impediments facing investors and businesses as well as help attract foreign direct investment. The country, he says, may not be rich in oil but it has enormous wealth in its young, tech-savvy population.

Expansion, however, is of little use if it isn’t sustainable. Sarah El Battouty discusses the importance of preserving, and stepping up, Egypt’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), be they environmental or developmental. The pandemic hit Egypt’s weakest hardest, among them women and rural and impoverished communities. Reconsidering the SDGs to enable resilience and equality requires flexibility in policy and shifting of investments beyond the conventional growth of Egypt’s economy. Above all, adaptation must promote resilience.

As much as it looks inward, though, Egypt must also look outwards. Both Deborah Lehr and Yasser Elnaggar explore Egypt’s trade options. The chaos caused by the pandemic has accelerated competition for business and investment between emerging economies. Lehr takes a look at Egypt’s trade relations with China, while Elnaggar dissects the advantages, and vulnerabilities, of Egypt’s investment and trade environment.

Last, but by no means least, Abla Abdel-Latif shines a spotlight on the major reason for the economy’s weaknesses. The Pavlovian response to external shocks has always been an over-reliance on fiscal and monetary policies. The real solution is to tackle the urgent need for basic structural reforms.

Mirette F. Mabrouk is a Senior Fellow and Director of MEI’s Egypt Program.

Endnotes

1. Reuters Staff, “Egypt’s budget deficit falls to 7.8% in FY2019-20,” Reuters, July 29, 2020,

www.reuters.com/article/egypt-economy/update-1-egypts-budget-deficit-falls-to-7-8-in-fy-2019-20-cabinet-idUSL5N2F056R.

2. “World Investment Report 2019,” UN Conference on Trade and Development, June 12, 2019, https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/wir2019_en.pdf.

3. “IMF Executive Board Approves US$2.772 Billion in Emergency Support to Egypt to Address the COVID-19 Pandemic,” IMF, May 11, 2020, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/05/11/pr20215-egypt-imf-execu….

4. “IMF Executive Board Approves 12-month US$5.2 Billion Stand-By Arrangement for Egypt,” IMF, June 26, 2020, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/06/26/pr20248-egypt-imf-execu…

“A review of Egypt’s experience with external shocks suggests that its economy is very vulnerable and lacks resilience.”

COVID-19 in Egypt: The Return of Harsh Realities

Samer Atallah

We have witnessed the severe effects of the COVID-19 shock across the globe. These have put a strain on all national economies, but, unsurprisingly, those resilient to shocks have been better able to mitigate the impact swiftly and smoothly. More importantly, they will most likely be able to rebound faster and end up healthier. In the case of the Egyptian economy, COVID-19 has hit critical sectors hard, mainly services (above all tourism), remittances, and the oil sector. It has also exposed the state’s inability to provide a secure, accessible safety net for most of the working population, who lack formal contractual agreements. All of this happened after three years of harsh austerity measures that were adopted as part of the economic program sponsored by the International Monetary Fund. The program improved macroeconomic indicators, but did not move the economy away from its traditional reliance on rent economic activities and capital-intensive sectors, such as the oil and minerals extraction industries.

All of these factors combined left Egyptian policymakers facing a dilemma. On the one hand, they could enforce a severe lockdown to preserve public health and protect the ailing public health system from collapse; this would come at the cost of preventing millions of Egyptians from working and generating income. On the other hand, they could relax the lockdown measures, allowing people to work but risking high fatalities given the inability of the health system to deal with the virus. Facing this difficult trade-off, the Egyptian government attempted to strike a balance. Arguably, a lot of effort and political will has been invested in ensuring a sound macroeconomic environment at the expense of building a resilient safety net and providing equitable access to quality medical services. One could also argue that such a trade-off would not exist in the first place if public resources were directed toward programs that guarantee support for the vulnerable and provide adequate and equitable access to public services. Instead, scarce public resources went to mega-projects with questionable or unverifiable economic and financial returns.

Economic vulnerabilities

At the onset of 2020, many believed that Egypt was finally turning the page on years of turbulence, both political and economic. Yet, a closer look would have supported the view that the path ahead was risky. A review of Egypt’s experience with external shocks suggests that its economy is very vulnerable and lacks resilience, primarily due to its reliance on tourism, remittances, and the Suez Canal as sources of foreign currency earnings. Non-oil exports have not expanded beyond Egypt’s traditional markets — mainly the southern EU countries, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia — and as a whole exports are still the outcome of very weak value chains. Foreign investment is confined to portfolio investment in government debt instruments. The COVID-19 shock was unusual in that it affected all fronts at the same time and with severity. Having said that, one imminent risk is the tendency to rely on relatively cheaper external financing to compensate for the reduction in external sources of income. This is especially risky given the high degree of uncertainty when it comes to tourism and remittances from oil exporting countries.

The impact of COVID on the global economy was and still is very severe. But in the Egyptian case, its severity is exacerbated by the lack of programs providing some sort of safety net or social protection, such as unemployment benefits. The recent results published by the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS) are very indicative of the severity of the impact. The supply shock has negatively affected the employment conditions of 61.9 percent of workers, with 20 percent having lost their jobs. Of those who are negatively affected, 41 percent can no longer afford their standard of living. As is typical in Egypt, the young, the uneducated, and the rural population are disproportionately affected. The impact on income generation has led Egyptian households to turn to conventional coping mechanisms, such as informal borrowing and reduced consumption of high-protein foods, such as meat. The government programs to support informal workers have only reached 5.4 percent of households. The difference between the impact on households and the reach of government programs is staggering.

The general perception among Egyptian households is that their income and jobs were affected because of the precautionary measures implemented by the government. An estimated 60 percent of the change of income was due to these measures. It is therefore easy to deduce that the motives for the recent government decisions to ease restrictions on mobility and open up commercial activities are almost exclusively economic and political in nature, overriding public health concerns.

Weaknesses in health & infrastructure

In addition to Egypt’s economic weakness, the weaknesses of its health system and infrastructure have also become evident. Indeed, COVID-19 has been a moment of truth for all nations’ health infrastructure. Egypt’s ailing health system was forced to face a harsh, yet simple, reality: It cannot deliver basic services. Not only is the infrastructure inadequate and unequally distributed geographically, Egyptians end up paying a large portion of their expenditure as out-of-pocket payments — among the highest rates in the region. Another major problem is the inequitable access to pandemic-related medical services, such as diagnosis and testing. Reports of families rushing to hospitals only to be denied testing and sent away are well documented. At the same time, private clinics and hospitals are able to charge a hefty price for tests, an indication of the government’s failure to regulate the private provision of health care. Most importantly, the pandemic was, in a way, an opportunity for the government to address grievances that doctors and health care providers had been expressing for years. Yet it was unable to meet even basic demands, such as the provision of personal protective equipment.

Moving forward, there is an urgent need to redesign social protection programs and safety nets. The current program that the government has enacted is extremely limited in its scope and does not provide the minimum means of subsistence. One policy that would have an immediate effect is a wide, generous, and government-sponsored program for unemployment insurance. This is a policy tool that could mitigate the effects of shocks in the economy on a large scale. Such a program should be designed to target poorer regions in particular. It should also be attached to periodically revised conditionalities, including one or several of the following: vocational training, educational attainment, and active pursuit of employment.

Another immediate and much-needed policy intervention is to reconsider public expenditure on health in terms of scale and distribution. The government has recently announced a 46 percent increase to nearly $16 billion for FY2021. This is commendable, but there must be a guarantee that it is not merely a one-time response to the pandemic. The health sector has long suffered from poor financing, and there is a pressing need to sustain such increases over several years. This increase in resources must be complemented by a plan to ensure a minimum level of public health service that is accessible, especially to the most vulnerable. To this end, the government should target the most impoverished cities and villages, which are mostly located in Upper Egypt. The allocation of public resources should be based on simple determinants such as the per capita number of medical facilities, medical beds, and health care professionals. In parallel, the government needs to expedite its rollout of the universal health care program in order to cover the whole country within the next two years. This long-term program, if implemented with the correct incentives for public and private health providers, should substantially reduce the out-of-pocket expenses paid by Egyptians, with financing provided by taxes and user subscription fees. These two policy interventions must go hand in hand. Health facilities that few can afford is no solution, nor is a universal health care policy with inadequate medical infrastructure.

The need for resilience

Lastly, the Egyptian economy must become more resilient. This must be done through job creation in formal, labor-intensive sectors. For job creation to sustainably generate value not only for workers but for the whole economy, it must be tied to export-oriented firms and sectors by creating linkages with exporting firms. To achieve this, investment and trade policy must work together toward a common purpose. Investment policy must incentivize investments in exportable, labor-intensive commodities and incentivize larger firms to rely on small and medium-sized enterprises for procurement. Trade policy must target new markets and expand old markets for such goods. The government should leverage its export subsidy program by fostering these linkages so that exporting firms can expand their footprint in the international market and non-exporting firms can expand beyond the domestic market. Overall, there is a need to improve the investment climate so that the capital markets direct investments into employment-generating industries.

Dealing with uncertainty is the daily task of policymakers. These are not easy times for any of them, and Egyptian policymakers are no exception in this regard. The current situation, however, also presents an opportunity. As long as they can learn lessons from the pandemic, they have a chance to save Egypt’s economy from severe downturns caused by current and future shocks. Policy inaction vis-à-vis the harsh and deep-rooted realities of the Egyptian economy carries considerable risks, especially after almost five years of difficult economic conditions and a completely sealed political space. It is impossible to sustain economic growth that, while benefiting a select few, leads to increased poverty, low-quality jobs, and significant youth unemployment, especially among the educated. Modes of social protection need to be revisited and redesigned. Also, all other economic policies must be geared toward real employment generation. Otherwise, a large part of the population will suffer tremendously. It is doubtful that policymakers in Egypt have an appetite for such political costs. If Egypt fails to ensure social protection, equitable health care services, and job creation for its citizens, the ingredients for growing social unrest will all be present. Policy interventions in these three areas will improve the economic inclusion of large segments of society and reduce political instability. Otherwise, dealing with COVID-19 will be just one of many worries for the Egyptian government.

Samer Atallah, PhD, is an Associate Professor of Economics at the American University in Cairo.

Endnotes

1. “Study on the Impact of COVID-19 on Egyptian Households,” CAPMAS, retrieved from http://www.capmas.gov.eg.

2. Ibid.

"The disruption caused by the pandemic should push Egypt collectively as a nation … to further coordinate its efforts, and to think more creatively and ambitiously.”

Does Digital Transformation Present an Opportunity for Egypt to Autocorrect?

Sherif Kamel

Since the turn of the 21st century, disruption has come in different shapes and forms. In recent years, when people talked about disruption, they usually meant the impact that information and communications technology (ICT) had on individuals, organizations, and society. However, since the last few weeks of 2019, the world has been hit with a perfect storm in the form of a disruptive pandemic that has affected both developed and emerging economies alike.

The disruption caused by COVID-19 was invisible, resembling a stealth attack. It started in Wuhan, China and in no time, it spread all over the world. The pandemic has caused a global shock that has led to a slowdown in economies, affected financial markets, and disrupted supply chains, requiring immediate worldwide coordination and the development of collective measures to combat it. Meanwhile, the precautionary health and safety measures including social distancing and the economic repercussions have led to millions around the world being forced to work remotely or losing their jobs.

Before these developments, in many ways, globally we were living in an age of pervasive and unprecedented uncertainty, although it is nothing compared to what we have seen recently. The current disruption is impacting societies around the world politically, economically, and socially. It is affecting the way people live, work, study, travel, communicate, stay healthy, and are entertained. It is still too early to tell, but the world will most likely witness a U-shaped recession with a potential recovery that will take around two years, and that will hopefully be followed by an upswing in the economy, which will vary from one country to another. In the meantime, however, countries are being hit by multiple rapid developments — falling oil prices, disruptions to trade, volatile stock markets, and severe hits to businesses — that have forced governments to pass comprehensive and extraordinary policies aimed at stimulating their economies and preventing mass layoffs and business shutdowns, especially among small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

It goes without saying that there is nothing remotely good about societies being affected by a pandemic, the magnitude of which has rallied countries around the world to coordinate their efforts to work against a common enemy. However, can the coronavirus have some collateral positives as well? Are there opportunities that can be created through digital transformation? Could this be a wake-up call? Can emerging innovative technologies such as artificial intelligence, big or rather smart data, the Internet of Things, blockchain, 3D printing, robotics, drones, cloud computing, and the like be real game changers for global society?

For starters, the current crisis is already forcing people around the world to adapt and use different technology platforms much more than ever before. Furthermore, the merging of infotech and biotech is proving that there will be no boundaries to the prospects for what lies ahead, and that it will take a brand-new leadership style as well as an innovative approach to navigate the emerging realities of the fourth industrial revolution.

What does this mean for Egypt?

When it comes to Egypt, recent events have demonstrated the importance of assessing its ability to adopt digital transformation in government practices, business transactions, and across society to mitigate the impact of disruptions such as that caused by COVID-19. Moving forward, building and regularly enhancing the necessary infostructure and infrastructure to support and enable digital transformation will be indispensable for individuals, organizations, and societies, Egypt included. This will allow them to stay relevant, competitive, and agile, as well as support them in not just remaining healthy and surviving the repercussions for the economy, but also in staying safe and thriving in a post-pandemic world.

The disruption caused by the pandemic should push Egypt collectively as a nation — including the government as an enabler, the private sector as a driver, and the civil society as a supporter — to further coordinate its efforts, and to think more creatively and ambitiously. This could include intensifying investments in infrastructure, such as health care, pharmaceuticals, and ICT, as well as upskilling the technology-related capacities of one of the country’s most precious assets, its human capital, to meet the requirements of digital transformation. This would, in turn, help to accelerate the development of a number of key sectors and priority issues, such as health, education, and financial inclusion, all of which have huge potential to boom. There is also an urgent need to support micro-enterprises and SMEs, and integrate the informal sector into the economy, while keeping an eye on issues like promoting food and energy security and expanding social protection and safety net programs. In addition, there should be an emphasis on job creation for the most vulnerable segments in society, including women, youth, and day-to-day informal workers.

As society moves forward while visualizing and projecting the new normal, the policies formulated and decisions taken should be thoughtful and purpose-driven to help support a stronger private sector, improved productivity, more resilient businesses and industries, and a digitally driven government. The future will be decided by the choices and decisions made today by governments, organizations, and individuals. Egypt, like many other countries, is facing a huge dilemma, in which the objective is to get the economy back on track while safeguarding the health and safety of its people, which is the nation’s utmost priority. Egypt’s action plan to control the impact of COVID-19 will be critical for navigating these difficult times, mitigating risks, protecting the economy, and helping it rebound successfully.

Before the pandemic hit Egypt, the country had been doing quite well: Economic growth came in at 5.6 percent in FY2018/19 and was projected to reach 6 percent in FY2019/20. The economy was among the best performing in emerging markets, and the macroeconomic indicators were all heading in a positive direction following a series of macroeconomic and structural reforms. These have helped stimulate growth, generate a solid primary budget surplus, reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio, lower inflation rates, and replenish foreign reserves. Egypt was enjoying strong foreign exchange buffers as 2019 remittances stood at $26.8 billion, tourism revenues were at an all-time high of $13 billion, and Suez Canal receipts were $5.9 billion. Collectively, this put the country in a better position to absorb the impact of the pandemic than it had been a few years earlier.

Responding to the pandemic

Since the early days of the pandemic, the government of Egypt has taken several measures to curb the spread of the virus, including health, safety, monetary, and fiscal policy responses that aimed to protect the population and ease the economic impact. These policy responses included allocating a budget of $6.4 billion (1.6 percent of GDP) to stimulate the economy by providing easier access to credit to help households and individuals, including informal workers, continue consumption, as well as providing liquidity for employment protection and unemployment benefits, and offering preferential interest rates to help firms, especially SMEs, survive the disruption. Other policy responses included imposing curfew schedules, introducing remote working, reducing staff working hours and limiting the number of staff per shift in necessary positions, reducing interest rates by 350 basis points, increasing liquidity in the stock market by $1.2 billion, slashing tax dividends by 50 percent for listed companies, reducing interest rates on housing for low-income and middle-class families, reducing energy costs for the industrial sector, suspending the tax law on agriculture land for two years, and expanding the social protection programs Takaful (Solidarity) and Karama (Dignity) by adding 10 million beneficiaries. In addition, the government’s plans include increasing investments in the health care and education sectors during FY2020/21 and raising pensions by 14 percent.

Despite the impact of the pandemic, Egypt’s government is determined to continue its progress in accelerating structural reforms. Judging by the developments of the first quarter of 2020, digital transformation could play a major role in the government’s future reform plans as it navigates the current crisis while keeping an eye on launching another wave of reforms that would not only build on the hard-won macroeconomic stability achieved over the past few years, but also address the longstanding impediments to a competitive private sector-led economic transformation. Consequently, the next reforms should focus on issues like reducing bureaucracy, red tape, and non-tariff barriers; making finance more accessible; and facilitating private sector access to key economic building blocks, such as land and skilled human capital. Such access will allow the private sector to expand given the diversified nature of Egypt’s economy, which could also lead to more job opportunities, economic development, and growth that could improve the prosperity of society and reduce poverty levels.

Egypt’s population is growing at an annual rate of 1.9 percent, or over 2 million people, and technology access has been rapidly increasing across the country, with 59 percent and 99 percent internet and mobile penetration rates, respectively. No less than 60 percent of the population is under the age of 30, reflecting a young society in a nation that is home to more than 100 million citizens. Both elements provide a unique opening for change and improvement. The intersection of youth, with its energy, ambition, and passion, with technology dissemination and utilization and a growing interest in self-employment could create a platform for a tech-based and tech-enabled entrepreneurial space. Furthermore, the universal access to ICT across Egypt’s 27 governorates could be an effective contributor and enabler for digital transformation by providing unlimited access to knowledge, opportunities, ideas, and the world at large for Egyptians, regardless of time differences and distance.

Digital transformation offers promise, but it needs support

Digital transformation offers ample opportunities for Egypt. However, innovation in general, and ICT in particular, cannot solve all the problems or answer all the economic and societal challenges that have developed over many decades. While digital transformation represents an enabling environment that can make a difference, it should be supported by the required infrastructure and skilled human capital, as well as the proper legal, regulatory, investment, governance, educational, security, and other support environments, in addition to an integrated ecosystem. The name of the game is to invest in creating a pool of tech-savvy entrepreneurs and scale up the number of innovative tech-based and tech-enabled start-ups through the establishment of incubators across Egypt’s universities and higher education institutions. In these incubators, the role of youth, practitioners, academics, industry experts, policymakers, business leaders, mentors, investors, innovators, educators, and trainers can never be discounted. It is a collective effort in which everyone should be effectively engaged and empowered.

For starters, as the world prepares for the post-pandemic norm, Egypt as a nation needs to change its mindset and think in a competitive, agile, and growth-oriented way that has at its core the private sector as a driver. Given current global developments, this will be timely, because it is expected that capital inflows and investments from around the world will be looking for countries that were less affected by the pandemic. This creates a variety of opportunities for different countries, including Egypt — given the current number of cases — that can act efficiently and expeditiously to create an environment conducive to attracting such inflows of capital.

As a repercussion of the crisis, corporates will probably pivot away from current business, manufacturing, and operating models, including global supply chains in which companies found themselves vulnerable and exposed, not only in terms of business and trade transactions, but also in the provision of health-related products including ventilators and personal protective equipment. Accordingly, corporates will be looking for more resilient and diversified alternatives, including sourcing and distribution logistics that are more local or regional — in other words, closer to end markets. This will lead to a trend of deglobalization, presenting a huge opportunity for Egypt’s industries and manufacturers. With its geographical location and portfolio of free trade agreements, Egypt can be a gateway for Africa. In addition, with its diversified economy and manufacturing base, as well as its skilled and competitively priced human capital, Egypt has the potential to become one of the primary global manufacturing destinations and an integral component of the global value chain by offering the right incentives and motivations, coupled with an enticing legal and regulatory environment.

Digital transformation can help reshape economies and societies, and improve their competitiveness, by stimulating creativity and innovation, generating greater efficiencies, and improving various services, as well as through offering a platform for inclusive and sustainable development and growth. Accordingly, Egypt has an opportunity to capitalize on digital transformation and work toward the goals of its Vision 2030 development strategy by: (a) unleashing the potential of the private sector; (b) digitizing various government services, which can have the positive effects of facilitating access to services for citizens, improving efficiency, reducing bureaucracy, and assisting the government in combating corruption; and (c) leveraging human capital capacities, with a focus on emerging technologies and investing methodically in building Egypt’s innovation capital.

In addition, digitization can offer a seamless platform for customs and tax processes that can remove the impediments facing investors and businesses and help attract more foreign direct investment; the latter has proven relatively difficult to achieve in recent years, especially when compared to pre-2011 levels. There are many other opportunities for digitization across different sectors that can improve efficiency and reduce costs, including in health care, education, trade, retail, agriculture, manufacturing, and transportation and logistics, to mention a few. It is important to note that while digital transformation will result in many jobs being replaced by machines in the future, new technology-related jobs will be created. Therefore, policies must be in place to provide sufficient training, human capital development, and social welfare to enable the labor force to embrace and adapt to the continuous changes taking place, and have the capacities and skillset to understand and make the most of the prospects enabled through emerging innovative technology platforms.

Local innovative tech-enabled start-ups

Furthermore, timing could provide a unique break because it is often advisable to venture into a new business in difficult economic conditions as it minimizes the cost and offers an opportunity to be ready to thrive when circumstances improve. Accordingly, the growing crowd of innovative and talented tech entrepreneurs in Egypt could be influential and participate in the country’s digital transformation. The following is a sample of promising tech-based and tech-enabled start-ups that address key issues of primary importance to society, such as transportation, financial technology (fintech), health care, logistics, and distribution.

In transportation, Swvl — established in 2017 and known as the Uber of buses — is a premium alternative to public transport in Egypt. Through a mobile app, customers can book fixed-rate and affordable bus rides on existing routes; this is an effective solution that is much needed, given the traffic and transportation challenges in Egypt’s major cities. Swvl is now operating in Egypt, Kenya, and Pakistan. In fintech, Paymob is an electronic payment enabler established in 2013 that offers integrated infrastructure solutions empowering the masses with instruments that increase financial inclusion. In health care, Rology, established in 2017, is an on-demand teleradiology platform solving the problem of radiologist shortages and high latency in medical reports by remotely and instantly matching cases from hospitals all over the world with the optimum radiologist. Also, in health care, Vezeeta, launched in 2012, is a digital booking and practice management platform for physicians, clinics, and hospitals in the Middle East and North Africa region. In logistics, MaxAB, established in 2018, is an e-commerce wholesale food and grocery marketplace using data-driven technologies and innovative supply chains to best serve its customers. Finally, in distribution, Brimore, set up in 2017, is a social commerce and parallel distribution platform that allows local suppliers to have nationwide coverage through a network of individual distributors, mainly housewives, selling products in their circles using omnichannel (an integrated cross-channel retail strategy).

Egypt is a consumer of imported digital products and services as well as an exporter of digital services, recording total exports of $3.67 billion in FY2018/19. However, post-pandemic, there will be a clear opportunity to reap the digital dividends and increase the contribution and expand the role of the sector with concerted, coordinated actions by society at large, including the government, the private sector, and individuals. For example, financial inclusion is a key pillar of economic growth. Using innovative technologies such as fintech can help SMEs — which make up around 80 percent of the country’s firms — bridge financial inclusion gaps, move into the formal economy, and effectively improve their capacity to grow and compete.

Consequently, the Central Bank of Egypt is working closely with the government to achieve financial inclusion through several projects, including promoting the notion of a cashless society and disseminating the use of electronic payments. In Egypt, cash is king and therefore represents one of the most attractive markets for unconventional and innovative financial technology platforms such as fintech. The size of the population — which includes a huge unbanked segment, with no more than 15 percent of the adult population having a bank account, one of the lowest penetration rates in the world — demonstrates the potential for growth. Fintech started growing in Egypt in 2008, providing solutions including electronic payments for peer-to-peer transfers and bills, payroll, and pension and social security payments; merchant and online purchases; and the proliferation of smart wallets. Moreover, fintech has the potential to offer the unbanked segment of society valuable services such as paying back their loans and transferring money through kiosks across the country. It is expected that COVID-19 will accelerate the move toward mobile services, which will have positive implications, including gradually integrating large segments of the informal economy.

Changing behaviors & the shift to digital platforms

Furthermore, there is no doubt that the habits, attitudes, and behaviors of people will change as well. We are already seeing early signs of a general shift to digital platforms by both individuals and businesses. Since the outbreak of COVID-19, Egyptians have been using digital platforms to work, study, and shop like never before, and this trend is expected to gain momentum in the future. During the last few months, statistics from Egypt’s National Telecommunications Regulatory Authority show a significant surge in internet usage, including 87 percent and 18 percent increases in home and mobile internet consumption, respectively. This is in addition to a 131 percent rise in web browsing, along with significant growth in the use of mobile applications, with a 376 percent increase in accessing educational portals and websites. On this note, the government has already signaled that it will continue to invest heavily in ICT infrastructure to accommodate the proliferation in digital transformation and help stimulate the economy, including the volume of investments in internet speed — which is expected to increase to 40 Mbps by the end of 2020 — which have reached $1.6 billion. In addition, the government is targeting increasing internet access for both mobile and fixed internet to 75 percent of the population by the end of 2020. The ICT sector is a growing contributor to Egypt’s economy, accounting for 4 percent of GDP in FY2018/19, an increase of 14.3 percent from FY2017/18.

The impact of digital transformation is intended to go beyond connectivity to include economic empowerment and growth, while also increasing competitiveness. This includes the digital transformation of services through a state-of-the-art infrastructure supported by a robust legislative framework that enables electronic commerce, proper governance, data security, and the preservation of buyer and seller rights. For example, some of the initial digitally transformed services nationwide will include notarizations, driving license renewals, and utilities payments. The services will be available through various channels, including the government portal and a portfolio of mobile applications. Furthermore, Egypt Post can take advantage of the trust it has built up in society for more than 150 years, coupled with its proximity to citizens across the country through its 4,000 premises, to support micro-enterprises and SMEs by offering a variety of digital services. Other digital services in the pipeline include: (i) a comprehensive health insurance system; (ii) a farmers’ card to ensure the delivery of subsidies to their rightful beneficiaries, verify land acquisitions and cultivated areas in order to develop an integrated agricultural map, help measure the amount of water needed for agriculture, and clarify the gaps between production and consumption; and (iii) a restructuring of the national tax system aiming to achieve justice and order.

During the past few months, COVID-19 has changed the way many people live, businesses compete, and economies function. Moving forward, those who choose to make use of the opportunities enabled by digital transformation will be better positioned to adapt, compete, and succeed; those who do not will continuously be disrupted and outpaced. Sooner or later, pending the development and distribution of an affordable and globally accessible vaccine, life will go back to some kind of normalcy. However, the world as we know it may never be the same again, with digital transformation playing a major role in our lives and livelihoods.

Egypt is not known for being rich in oil, but it is blessed with one precious, invaluable asset: its youthful human capital. This resource can take Egypt forward through the creation of a tech-enabled entrepreneurial culture that can be scaled up across the country’s governorates. A well-established, innovation-driven, government-enabled, and private sector-led digital transformation strategy can be an effective platform to help grow the economy in a more competitive and inclusive way and presents a unique opportunity for Egypt to autocorrect.

Sherif Kamel is Professor and Dean of the School of Business at the American University in Cairo and President of AmCham Egypt.

“Policymakers once again faced the dilemma of livelihoods versus lives.”

As Egypt Recovers, Sustainable Growth Must Remain at the Heart of its Development Plans

Sarah El Battouty

Over the past few months, Egypt has been gradually reopening since it began easing COVID-19-related restrictions at the end of June. After peaking at nearly 1,800 new cases on June 19 and falling steadily during the month of July, the numbers have been largely stable throughout August and September, reaching the symbolic 100,000-case mark in early September.

This came after a difficult spring when the number of confirmed infections rose steadily throughout the month of Ramadan, starting in late April; the month began with 5,000 cases and ended with just under 16,000 right before the Eid al-Fitr holiday. A partial curfew starting at 5pm was imposed during Eid, with public restaurants, beaches, malls, and non-essential suppliers all remaining closed. All workers were required to wear masks and the public was encouraged to stay home and maintain social distancing. The elite social strata took measures to work from home and most gatherings were cancelled. Sporting clubs, cinemas, and arenas were closed, along with mosques, churches, and schools.

Downtown, however, was a different story. In the Cairo slums and markets people gathered in their hundreds in small buses, stations, and souqs, going about their daily routines while police frantically tried to oversee the closure of makeshift vendors and send youths gathered in groups home at 9pm. No masks or social distancing were evident. The government repeatedly cautioned the public, and a number of awareness campaigns were run and measures implemented, to little avail.

As has been the case in many other countries, a clear division emerged in Egyptian society: On one hand, there were calls for the government to enforce a complete lockdown, and on the other there were those who viewed a lockdown as a luxury that they and Egypt’s economy simply could not afford. Policymakers once again faced the dilemma of livelihoods versus lives.

Livelihoods & lockdown

The pandemic has exposed a need to improve nationwide communication and crisis management. Egypt released its three-phase plan for reopening with guidelines aimed at both the private and public sectors. However, the majority of the unregulated and informal sector was not addressed, and this contradiction posed a real threat. How can livelihoods be sustained if a complete lockdown is enforced? The closure of schools meant that half of the workforce was automatically confined by childcare, with parents forced to stay home and businesses having to implement measures to accommodate this. Compensation packages were introduced with the aim of reducing the impact of layoffs on daily laborers.

The informal sector accounts for as much as 70 percent of Egypt’s economy,1 and 90 percent of the total economy is made up of micro and small to medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs).2 More than half of the Egyptian workforce is employed in the MSME sector, and therefore the effects of the pandemic were felt most sharply by those who could least afford it, at the bottom of the income pyramid. Efforts to mitigate the impact of the pandemic on informal labor highlight the need for formalized data and incentives to promote knowledge-based decisions and greater inclusion. As the past few months have made clear, reliance on public awareness to make preventative and protective measures work is not enough by itself to bring down the infection rate or buy time to build new quarantine units and hospitals. All institutions, companies, and NGOs have been mobilized to respond to the crisis with a goal of softening the immediate impacts, and it is critical that the partnerships formed between them remain intact in the longer term, beyond the current crisis.

Egypt’s government may have been hesitant about enforcing an extended lockdown due to the impact on employment, but this reluctance comes at the cost of denying all sectors the ability to plan ahead. For small businesses, efforts have been made to advise on crisis management as Egypt’s youth have taken online tutorials on how to survive and plan for the worst-case scenario. How this collective effort is disseminated to the majority of the Egyptian workforce who are not so familiar with digital resources is a pressing question, however.

Egypt’s economic trajectory

While the International Monetary Fund projects3 that the MENA region as a whole will see a 4.7 percent decline in economic growth in 2020, Egypt’s growth rate for the year is expected to remain positive, falling from the previously forecast 5 percent to 2 percent. So while developed economies may face the prospects of a deep recession, Egypt will have to contend with a brake on its upward economic curve that may throw the country off the path of reform and recovery it has been on since the economic devastation that accompanied the Arab Spring in 2011. Just as tourism numbers and growth were recovering after the floatation of the currency in 2018, and a slight increase was seen in foreign direct investment in 2019, COVID-19 has knocked the country off course.

This brings us to the sustainable development pathway that has accompanied Egypt’s economic growth road map. Vision 20304 set targets for sustained livelihoods and the provision of better services in health care, insurance, social protection, and education, prioritizing them to promote Egypt’s stability and paving the way for policies that meet the demands of a predominantly young and growing population. COVID-19 has undoubtedly affected economic and social planning, with crisis management and unforeseen circumstances causing disruptions to both the public and private sectors. The Ministry of Planning and Economic Development and the banking sector have acted fast to assist entrepreneurs in developing models for which businesses and vulnerable groups to prioritize. Winners and losers have emerged from the pandemic, with health care, agriculture, and green businesses seeing opportunity, while manufacturing, exports, and construction have all witnessed losses. In short, the larger employers have suffered the most.

The pandemic has exposed weaknesses in global health care and crisis management, and it may not be possible for countries with lower resilience and economies that are still recovering, such as Egypt, to achieve the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030. The vulnerability of low-income groups, women, laborers, and small businesses has been magnified. Health care, jobs, and education have all been negatively impacted, with government resources being dedicated to addressing the immediate and short-term effects nationwide. What needs to be considered now are the wider and deeper effects of the pandemic, such as vulnerable groups falling behind, water shortages, and a slowing economy in the medium and longer term.

Social & environmental challenges

In the Middle East, and especially Egypt, lifestyles have to be taken into consideration as well. Social distancing may not be as easy to adopt because of family structures. Egyptians tend to have larger households, with grandparents, parents, and children living together. Isolating senior citizens from children is difficult, as the elderly often live at home and children typically do not leave the family home until they marry. Social distancing is also antithetical to the norms of greetings, gatherings, and interaction that are an integral part of life in much of the Middle East and North Africa. In addition, reproductive health and awareness have seen a decline, with women and children requiring social solidarity protection.

Another potential challenge is water shortages and growing domestic energy use as people are confined to their homes. The Ministry of Environment confirmed that pollution levels have decreased in cities and air quality has improved due to the lack of industrial and transport activity, but food shortages, lack of imports, and slower production in the agricultural sector will result in price hikes in the near future. The cycle of economic shocks that is all too familiar in Egypt has suddenly intensified and accelerated. The issue of waste management in poorer communities must not be ignored in efforts to address the consequences of shifts in government spending priorities.

Proponents of the SDGs embraced globally in early 2020 argue that now is the time to reinforce the commitments and revisit the challenges with a greater focus on prevention and resistance. As a potential COVID-19 vaccine and recovery draw closer, maintaining a social, economic, and environmental balance has never been as critical as it is today. A global phenomenon like the pandemic has a unique ability to bring governments and people together and the resulting opportunity to rebuild corrective measures must be seized.

From another perspective there is a call to revisit or restructure the sustainable development pathways, as new segments like employers and middle-income groups now count themselves among the vulnerable, amid rising debts and loans. In the face of this challenging environment, how can sustainable jobs be created? How will poverty be universally eradicated? Where and how will human rights be promoted if basic freedoms are hampered by lockdowns or restrictions? In a world of information, how can we ensure marginalized groups also have access? What will the psychological effects on children confined to their homes be?

The response to COVID-19 cannot be delinked from sustainable development entirely. It is therefore critically important that governments adapt their responses to different cultural and economic circumstances.

As Dr. Sherifa Fouad Sherif, executive director of the National Management Institute at the Ministry of Planning and Economic Development, recently noted, “Human well-being is the entry point for maximizing progress regarding the implementation of the SDGs. Acceleration in implementation of the SDGs is needed now more than ever. Increasing access to social protection, creating a strong health care system as well as investing in our human capital [are] of top priority. Greater collaboration and global knowledge sharing in science and technology is needed for the public good.”

Reconsidering the SDGs to enable resilience and equality requires flexibility in policy and shifting of investments beyond the conventional growth of Egypt’s economy. Planning and adapting must promote social resilience for Egypt to continue its economic growth. Engaging businesses and forming partnerships in planning are necessary parts of creating stimulus packages that are truly sustainable and not just cosmetic. Egypt has proposed a stimulus for some businesses, especially those in the tourism sector, yet more needs to be done to bring back jobs and above all the focus needs to be on a cleaner, less carbon-intensive growth plan, with an emphasis on innovation, renewables, and agricultural revival. The SDGs that are interlinked with environmental targets should take precedence in a post-pandemic recovery. For Egypt to evolve as it emerges from the crisis, sustainable growth must remain at the heart of its long-term vision.

Sarah El Battouty is a non-resident scholar at MEI, an award-winning architect with 18 years’ experience in the field of green and environmental building, and the founder of one of Egypt’s leading environmental design and auditing companies, ECOnsult.

Endnotes

1. Dr. Gita Subrahmanyam, “Addressing informality in Egypt,” North Africa Policy Series, AfDB, 2016, https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/Work….

2. “Business Climate Development Strategy Phase 1 Policy Assessment Egypt,” The Authority of the Steering Groups of the MENA-OECD Initiative, June 2010, https://www.oecd.org/global-relations/46341307.pdf.

3. “Regional Economic Outlook July 2020 Update,” International Monetary Fund, July 2020, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/REO/MECA/Issues/2020/07/13/regional….

4. “Egypt’s Vision 2030,” The Cabinet of Ministers, The Arab Republic of Egypt, https://cabinet.gov.eg/e371_8e49/GovernmentStrategy/pages/egypt’svision2030.aspx.

“Despite the onset of COVID-19, bilateral trade between China and Egypt ... reached a total of $5.2 billion as of the end of July.”

Opportunity Amid Adversity: COVID-19 Could Pave the Way for Closer Egypt-China Economic Ties

Deborah Lehr

Egypt appears to be weathering the economic fallout from the COVID-19 crisis better than many other emerging markets, but the global impact is still likely to take a heavy toll. Egypt’s key industries of tourism, construction, and retail have all been hard hit by the global economic shutdowns and dramatic drop in demand. Job creation, financial inclusion, foreign investment, and export promotion are key elements of any strategy to reenergize the economy. As President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi’s government develops its relief program, it might consider looking East instead of West for support.

Growing trade ties

Despite the onset of COVID-19, bilateral trade between China and Egypt increased by 3.2 percent year-over-year1 during first four months of 2020 and reached a total of $5.2 billion as of the end of July. While the rise is due in part to the medical supplies and other materials sent to Egypt as part of China’s “mask diplomacy” to provide support in fighting the virus, it is also a reflection of the opportunities that exist in Egypt for Chinese exporters. Imports of Chinese products to Egypt grew by 5.1 percent in the first four months of the year. Meanwhile, Egypt’s real GDP growth is expected to reach 3 percent in 2020, according to the World Bank,2 which distinguishes it from many of its neighbors as the only MENA country forecast to have positive growth rates.

China was also the first major economy to start fully functioning after the COVID-19 shutdown. While the United States slowly reopens parts of its economy, China has 98 percent3 of its factories running and almost 100 percent of its people back to work. And even as Americans begin to return to work, the Trump administration is looking inward, not outward, to stimulate growth. The administration’s focus has not been on opening new markets and promoting exports; instead, it has been to encourage the return of industries to U.S. shores and to support domestic consumption.

The worsening tensions between the United States and China will potentially benefit Egypt as well. The rhetoric between the two countries has reached a new low, with the Chinese state broadcaster accusing Secretary of State Mike Pompeo of being a liar4 on the nightly news, and Pompeo holding up a G-7 communique5 because U.S. allies would not agree to call COVID-19 the “Wuhan virus.” The rhetoric reflects growing and deepening tensions over technological competition, trade and investment restrictions, concerns over Hong Kong and China’s treatment of Uighur Muslims, and issues related to national security. And as the presidential campaign heats up ahead of the general election, tensions will only get worse before they get better.

Solidarity & opportunity

Unlike the U.S. and Europe, governments in the MENA countries by and large have not publicly been critical of China’s initial handling of the coronavirus and, in some cases, have even praised its efforts. Egypt sent its health minister to China6 in a sign of solidarity, while presidents Sisi and Xi Jinping spoke by phone7 about cooperating to handle the virus. Egypt also sent medical supplies to China8 during the initial outbreak, and China returned the favor9 as the virus spread to Cairo.

In addition to the goodwill generated, Egypt stands to benefit from China’s own relief program, recently announced at the National People’s Congress, the country’s most important political meeting of the year. China is seeking to stimulate its economy in two ways. First, by introducing policies and providing aid to create jobs. The private sector is the largest engine of growth, providing 80 percent10 of urban employment, and therefore is the vehicle for increasing employment. These firms, as well as some state-owned enterprises, are being encouraged and supported financially to expand both at home and abroad. Exporting and seeking new sources of investment are therefore key priorities. And with economies in the West slowing and the atmosphere unwelcoming, the MENA region is an increasingly attractive destination for Chinese firms to expand.

Egypt will also find the Chinese leadership’s pledge to support the development of “new” and “old” infrastructure11 appealing. The build-out of “data” infrastructure to facilitate the move to 5G will be transformational and disruptive across most major industries. Beijing intends to spend up to $2.5 trillion12 over six years to support the building of China’s digital future — which they want to take global. Chinese firms lead the world in creating the 5G networks that will allow growth of the “Internet of Things,” fintech, smart cities, self-driving cars, artificial intelligence, facial recognition technologies, and so much more. For countries like Egypt, Chinese technology provides the opportunity to leapfrog old technologies into the modern world at competitive prices.

Sustainable development & green finance

As Egypt looks to develop its own strategy for sustainable development and green finance, Chinese capital and technology will be an attractive option. It should explore ways to cooperate with China but also to develop projects and products that will attract Chinese capital seeking green investments. President Xi has stated that he wants China’s new and old infrastructure growth to be “green.” China is seeking to be a leader in sustainable development and to promote this effort along the countries of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), President Xi’s signature foreign policy initiative.

In recent years, China has established over 600 green private-equity funds,13 is now one of the largest issuers of green bonds, and has launched14 the largest carbon-exchange market in the world. Chinese firms are developing cutting-edge applications through the use of technologies such as artificial intelligence and fintech to support sustainable small and medium-sized industries. China is also now the leading producer of new-energy vehicles, and as its own market becomes competitive, these firms are seeking new ventures overseas. Given that Egypt is just developing its own policies on sustainability, it is an opportunity to be innovative. One strategy would be to establish an Egypt-China green fund, for example, modeled after the successful U.S.-China Green Fund, to facilitate the trade of sustainable products, know-how, and technologies between the two countries.

As China’s economy has slowed, there has been a corresponding drop in Chinese investment to support BRI infrastructure development. Chinese state investors are less willing to invest in countries with greater risk, especially risk stemming from political uncertainty. Egypt stands out as an attractive market given its large population, stable political system, wired and technologically savvy population, and focus on major development projects. President Sisi’s intention to build new, modern cities like New Alamein and the New Administrative Capital should be a draw for Chinese investors seeking more stable investment opportunities.

Export opportunities

Another way China is looking to grow its economy is by promoting domestic consumption. At home, the government is finding ways to stimulate domestic demand and provide greater access to supply factors, such as land, labor, and even data. As part of this effort, it is opening major segments of the Chinese economy to foreign direct investment by providing financial incentives and welcoming imports.

Among the many suitable sectors for Egyptian exports is agriculture. China is actively making purchases abroad; citrus imports are expected to increase by 3 percent15 and Egypt is already one of China’s main suppliers. As industries in China ramp up production, energy needs will rise again, providing an opportunity to boost Egypt’s already significant exports of fuel and oil. There are also growing opportunities for retail companies, with demand increasing for overseas fashion and designs, as well as for services firms.

Lastly, as travel picks up, Egypt should take all necessary steps to reassure Chinese visitors that they will be safe visiting the country. Over the past three years, the number of Chinese visitors has been growing by about 30 percent16 annually, but from a small base. There is tremendous potential to grow these numbers if the tourism sector is developed in ways that make it attractive and safe for Chinese visitors.

China and Egypt have a long shared political and economic relationship, and it is poised to strengthen in the wake of COVID-19. During these difficult times, China can play an important role in Egypt’s economic recovery, and it will be seeking to build stronger ties through its “mask diplomacy” efforts in an attempt to mitigate criticism of its initial mishandling of the virus outbreak. There are still many unknowns in the weeks and months ahead, but there is an opportunity to be seized now — if Egypt acts.

Deborah Lehr is the CEO of Basilinna, a strategic business consulting firm focused on China and the Middle East; Vice Chairman and Executive Director of the Paulson Institute; and the founder and Chairman of the Antiquities Coalition.

Endnotes

1. “Volume of trade exchange between Egypt, China hits $4.31B in 4 months,” Egypt Today, June 8, 2020, https://www.egypttoday.com/Article/3/88406/Volume-of-trade-exchange-bet….

2. “Pandemic, Recession: The Global Economy in Crisis,” The World Bank, June 2020, https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/global-economic-prospects.

3. “More Than 98 pct of China’s Major Industrial Firms Resume Work,” Xinhua, March 30, 2020, https://www.yicaiglobal.com/news/more-than-98-pct-of-china-major-indust….

4. Anna Fifield, “China wasn’t wild about Mike Pompeo before the virus. It’s really gunning for him now,” Washington Post, April 30, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/china-mike-pompeo-cor….

5. Associated Press, “Pompeo, G-7 foreign minister spar over ‘Wuhan virus’,” Politico, March 25, 2020, https://www.politico.com/news/2020/03/25/mike-pompeo-g7-coronavirus-149….

6. “Egypt’s health minister flies to China to convey solidarity against coronavirus,” Xinhua, March 2, 2020, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-03/02/c_138833203.htm.

7. Egypt Today Staff, “Sisi phones China’s Xi Jinping for cooperation on combating COVID-19,” Egypt Today, March 23, 2020, https://www.egypttoday.com/Article/1/82933/Sisi-phones-China’s-Xi-Jinping-for-cooperation-on-combating-COVID.

8. Michael Boorstein and Sudarsan Raghavan, “Egypt sends military plane filled with medical aid to help U.S. with coronavirus,” Washington Post, April 20, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/religion/2020/04/20/egypt-military-plane….

9. “Egypt receives 3rd batch of anti-coronavirus medical aid from China,” CTGN Africa, May 16, 2020, https://africa.cgtn.com/2020/05/16/egypt-receives-3rd-batch-of-anti-cor….

10. “China Vows More Support for Private Sector to Stabilize Growth,” Caixin, December 24, 2019, https://www.caixinglobal.com/2019-12-24/china-vows-more-support-for-pri….

11. Jacky Wong, “China’s New Infrastructure Push Isn’t All New,” The Wall Street Journal, April 23, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-new-infrastructure-push-isnt-all-ne….

12. Gordon Watts, “China’s high-tech dream could come at a price,” Asia Times, June 10, 2020, https://asiatimes.com/2020/06/chinas-high-tech-dream-could-come-at-a-pr….

13. Deborah Lehr, “Why China needs to keep its economic recovery green and sustainable,” South China Morning Post, July 3, 2020, https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3091407/why-china-needs-ke….

14. Clare Saxon Ghauri, “China Launches World’s Biggest Carbon Market,” December 19, 2017, https://www.theclimategroup.org/news/china-launches-world-s-biggest-car….

15. “Citrus: World Markets and Trade,” United States Department of Agriculture, July 2020, https://apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/circulars/citrus.pdf.

16. “Feature: Egypt anticipates return to Chinese tourists after epidemic,” Xinhua, February 2, 2020, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-02/14/c_138784170.htm.

"The situation is disheartening, but it also provides an opportunity for the government to implement long-awaited structural reforms.”

Egypt and COVID-19: The Day After

Yasser Elnaggar

The Egyptian economy has undergone a series of fiscal and monetary reforms over the past four years. These reforms to eliminate subsidies, redesign the tax system, and liberalize the exchange rates were implemented at a significant social cost, but resulted in substantial improvements in macroeconomic indicators. However, some of the deeper structural reforms necessary to improve the overall economic situation were not realized. Now with COVID-19 impacting all economies around the globe, Egypt has the opportunity to emerge as one of the few winners from the current situation if it is willing to continue to push forward to better support the private sector, enhance fair competition, focus on job creation, tie the country more closely into global supply chains, and improve the climate for doing business in order to attract more foreign direct investment.

According to the minister of finance, government revenues were down by $7.75 billion while expenditures went up by $4 billion as a direct result of the COVID-19 crisis. The Central Bank of Egypt paid back almost $20 billion in debts to international financial and investment institutions over the four months through the end of June1 and expects to pay out another $5 billion over the course of the year. This is a significant and unanticipated financial outlay.

While the health and economic impact of the crisis cannot be underestimated, it is worth mentioning that the economic impact would have been even worse without the reforms implemented over the past four years. Against this backdrop, the government was able to adopt several measures to support the local economy, including a stimulus of $6.4 billion as well as tax incentives and holidays.

On April 28, the Egyptian cabinet announced a series of tax relief measures2 to stimulate the economy. These included: deferring capital gains tax until Dec. 31, 2021; reducing the withholding tax on dividends from 10 percent to 5 percent; and lowering the stamp tax on securities transactions from 0.15 percent to 0.05 percent. In May, President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi approved Law 24 of 20203 postponing real estate and income taxes along with workers’ contributions to the state pension.

The government also turned to the International Monetary Fund in May for rapid financing worth $2.7 billion, while another $5.2 billion for structural adjustment programs (to be disbursed over 12 months) was announced in June. In addition, the government is seeking almost $9 billion from international lenders.

These funds will no doubt help bridge the growing finance gap and reduce the budget deficit in FY2020/21, but such remedies are temporary in nature. If Egypt is to make a full recovery, it needs to adopt policies that structurally reform the economy, improve the business climate, support the private sector, reprioritize government spending in order to overhaul customs and tax regulations, invest in industrial infrastructure, and foster innovation.

As laid out below, there are some key structural challenges that must be addressed as well.

Legal & regulatory uncertainty

Laws and regulations seem to change every year or few years, and as a result the Egyptian economy lacks the necessary predictability and certainty for businesses to make long-term investments. Domestic and foreign investors have said that new laws and regulations that streamline the process of doing business are needed to encourage the private sector. Businesses, and especially foreign investors, depend on long-term planning, which is complicated when the regulatory structure changes frequently.

Protecting investments is another crucial area where laws need to be streamlined and simplified. The universal application of the rule of law and even-handed involvement from the state as a credible arbitrator provide investors with the confidence and assurances that they need.

Industrial development

The industrial sector, which accounts for 16.2 percent of GDP4 and at least 12 percent of employment, has been the hardest hit by COVID-19. Supply chains, especially from China, have been disrupted globally, which impacts Egypt’s production. Demand for Egyptian exports has fallen due to the general decline in global demand stemming from the pandemic. Furthermore, domestic demand has also shrunk as a result of the drop in Egyptians’ purchasing power and changes in consumer behavior.

While some food processing industries have benefited from the crisis, most other sectors continue to suffer. Some factories are operating at less than 50 percent of their capacity, resulting in greater unemployment. Some estimate that the industrial sector could shrink by as much as 50 percent5 in 2020.

In the garment and clothing industry, for example, almost 80 percent of export orders have been canceled, with estimated losses reaching $800 million by the second quarter of 2020. This is highly concerning as this sector is labor intensive and an important source of income for women in particular. The chairman of the Readymade Garments Export Council of Egypt, Magdy Tolba, told Egypt Today that the majority of the 350-400 garment factories in Egypt6 will be negatively affected by the decision of international brands to halt manufacturing worldwide.

While the government has been proactive in providing tax holidays and preferential loan mechanisms for industrial facilities, the cash flow crisis makes it hard for major sectors of the economy to continue operations. Enterprises large and small are feeling a cash crunch due to shrinking demand for non-essential products. The revenues of many companies have taken a severe blow, which makes it increasingly difficult to maintain working capital.

The situation is disheartening, but it also provides an opportunity for the government to implement long-awaited structural reforms that can mobilize domestic and international investments in industrial production. The state could, for example, provide land for industrial development at zero cost. It also should adopt policies to streamline permits, allowing companies to obtain these after starting operations rather than mandating prior approvals from numerous government entities.

In addition, with excess electricity production and low international prices for natural gas, the government should consider reviewing and potentially reducing the price of state-provided energy for some, or even all, industries. It was to the economy’s benefit when the government lowered the price of electricity by $0.006 (EGP0.10) per kilowatt hour,7 but Egypt must do more to incentivize industries as they face severe competition in export markets. Otherwise, relatively high prices for domestic inputs will harm the competitiveness of Egyptian exports.

State involvement

Over the past few years, the Egyptian government indicated its intention to launch public offerings for certain state-owned companies on the Egyptian stock market. However, as the minister of the public enterprise sector noted, the current climate is not conducive to initiating these public offerings; COVID-19 has impacted the stock market so severely that the government has earmarked around $1.875 billion to stabilize it.

One can argue that such offerings are the best avenue for the state to scale back or exit from certain economic activities, but this process should occur under favorable market conditions. The concern is that these companies will not turn into viable businesses if they continue to be managed by government appointees. Another option is for state-owned companies to offer strategic investors the controlling minority shares in subsidiaries that focus on consumer products. This would help to significantly shrink state ownership, while allowing investors to manage and operate those facilities.

Private sector: Tourism & tech

Job creation, particularly for Egypt’s youth, is a critical part of the economic recovery. The government should consider reprioritizing spending in support of the private sector, especially small business, which is the largest generator of jobs.

The tourism sector has been especially hit hard by the downturn, and the impact is broadly felt because it is so interconnected with the rest of the economy. Tourism accounts for about 12 percent of Egyptian GDP, and Egypt’s minister of tourism estimates that the country has been losing about $1 billion a month8 since the shutdown and will continue to do so until things return to normal. The government needs to be proactive, especially in working long term with small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which make up the majority of the sector but have limited financial reserves.

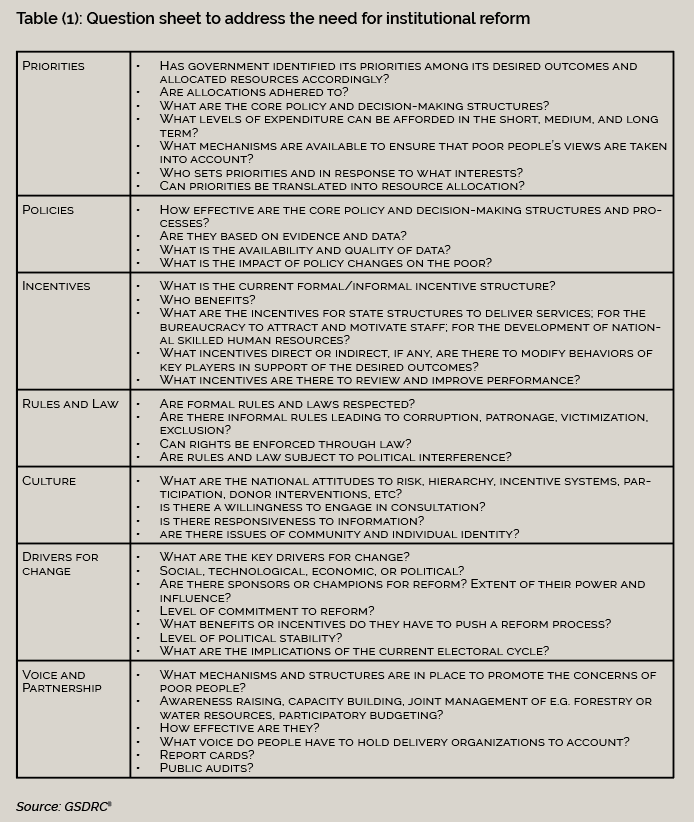

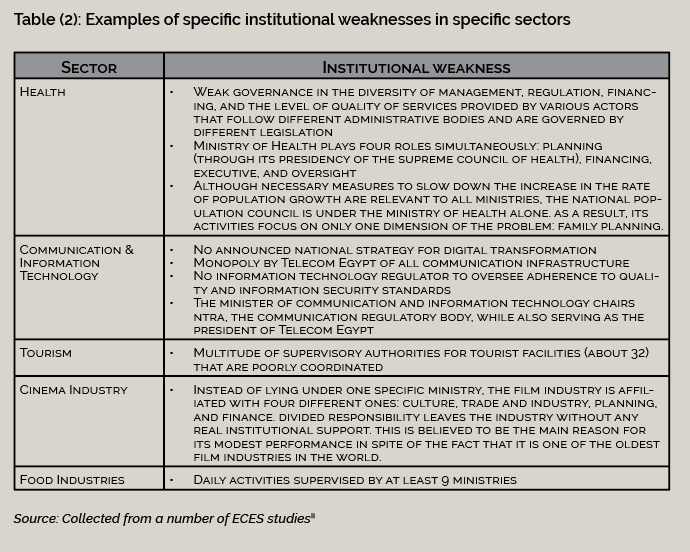

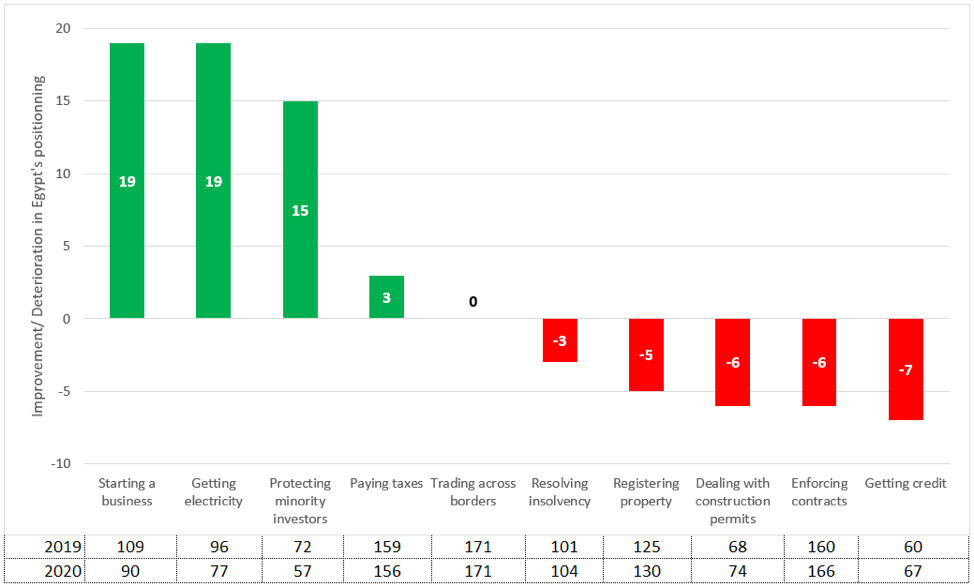

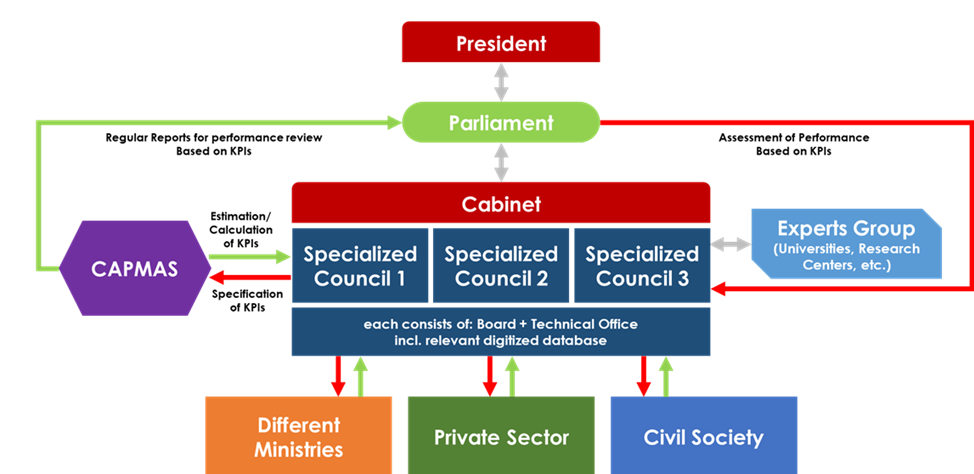

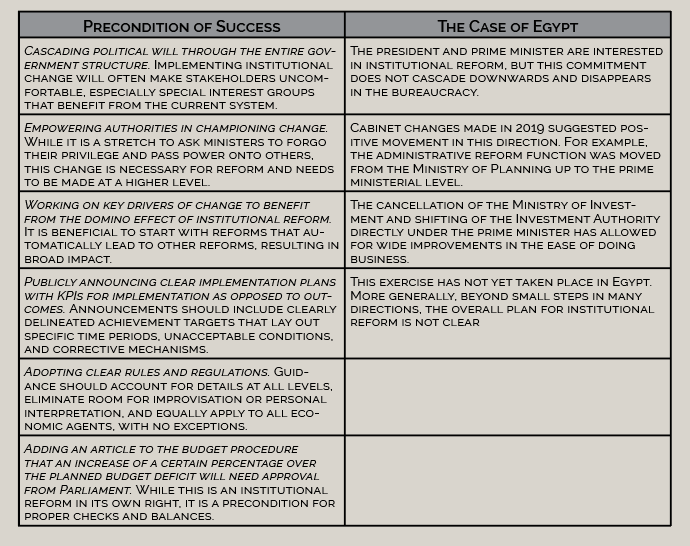

Another sector that would benefit from government support is the tech sector, which could become a major driver of growth through emerging technologies like artificial intelligence and 5G development. The IT sector was estimated to grow at a rate of over 13 percent a year from 2017-20, although the pandemic will likely have at least a temporary dampening effect on that.9 Egypt has a young, tech-savvy IT workforce, which is one of the largest in the world.