Key points

-

Of all the challenges to Saudi Vision 2030, none may be greater than Iran’s threat to Saudi national security. To succeed, Saudi Arabia must not only fortify its defenses against further Iranian and Houthi attacks but also establish a level of deterrence against Tehran.

-

Riyadh has three main deterrence options, which are not mutually exclusive: 1) diplomacy; 2) external protection; and 3) more effective military capabilities.

-

The diplomatic option is highly imperfect because of the profound discrepancy in threat perceptions and objectives between Saudi Arabia and Iran. That said, diplomacy is probably Riyadh’s best bet at present to preserve the calm and achieve deterrence.

-

Saudi Arabia could obtain official security guarantees from an external ally to prevent Iran from attacking it again. The two candidates that could play that role are the United States and possibly China. However, Saudi Arabia’s chances of securing a formal defense pact from China or the United States are not good, though the likelihood of enhanced security cooperation with the U.S. has increased.

-

To sustain peace for the long term, Saudi Arabia must develop more effective military capabilities. Currently, there is little in the Saudi military arsenal that could serve as a powerful deterrent against Iran. Riyadh’s determination to enhance its deterrent posture by escalating the development of ballistic missile capabilities is loaded with risks.

-

Washington may not be able to stop Saudi Arabia from proliferating and acquiring more powerful ballistic missiles, but through a whole new approach to military cooperation, it could help Riyadh develop its other military capabilities.

Introduction

Of all the challenges to Saudi Vision 20301 — Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s (MBS) high-stakes plan for life after oil — arguably none is greater than Iran’s threat to Saudi national security. To succeed, MBS must protect the kingdom, which will require not only fortifying its defenses against further Iranian and Houthi attacks but also establishing a level of deterrence against Tehran.

Riyadh has three main deterrence options, which are by no means mutually exclusive: 1) diplomacy; 2) external protection; and 3) more effective military capabilities. The diplomatic option, while highly imperfect, is probably Saudi Arabia’s best bet at present to preserve the calm. But to sustain the peace for the long term, there is no substitute for Saudi Arabia developing more effective military capabilities, especially since the option of external protection seems less than probable.

Security Is Paramount

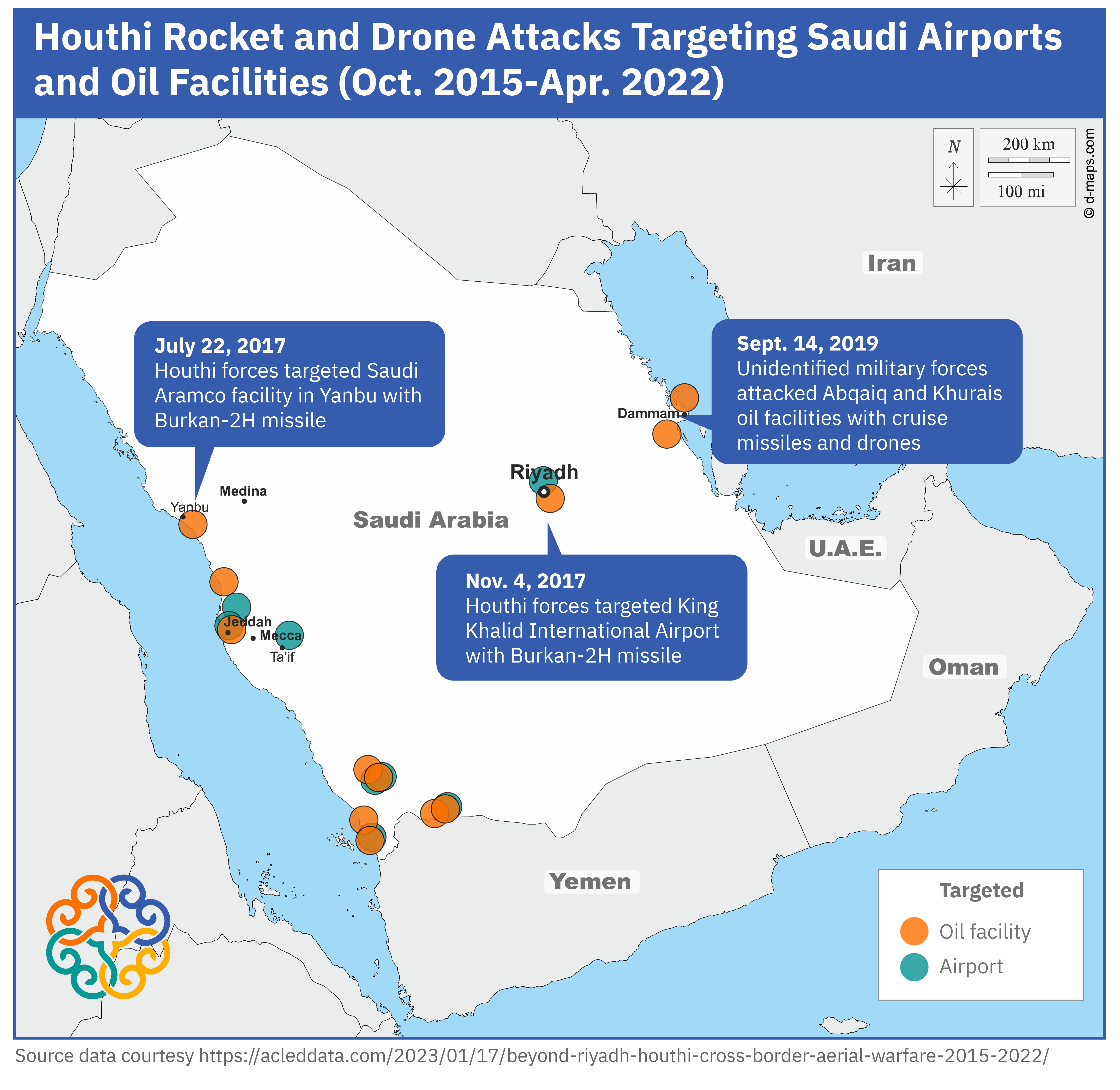

Security is integral to Saudi Arabia’s economic restructuring, especially on such a massive scale. Should the kingdom suffer another major conventional strike, like the one in September 2019, when Iran fired 25 drones and cruise missiles against Saudi oil processing facilities in Abqaiq (the largest oil processing and stabilization center in the world) and Khurais, or should the Iran-backed Houthis resume their kinetic attacks against Saudi civilian targets, Vision 2030 could be dealt a heavy blow.2 The September 2019 attack represented the single largest daily oil supply disruption in history, with 5.7 million barrels of Saudi crude production lost.3

Until its war in Yemen in 2015, Saudi Arabia was living in a relatively permissive security environment. To be sure, there were always tensions with Iran, and the threat of domestic or regional violent extremism was omnipresent. But the former never escalated to a military crisis, and the latter had been relatively contained since 2003, when the late al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden unleashed his Saudi henchmen on the kingdom and unsuccessfully tried to depose the House of Saud.4 Even at the height of the Islamic State threat in 2014, Saudi Arabia was relatively secure.

Saudi Arabia’s security situation began to deteriorate when the Houthis, a Yemeni rebel group supported by Tehran, overthrew the central government in Sanaa in September 2014 and later seized much of Yemen.5 Even though Yemen had been a thorn in the side of Saudi Arabia for several decades, this time the Saudis assessed that the Houthi takeover presented a more immediate threat to their national security given the militia’s direct and growing links to Iran. Iran arms the Houthis with sophisticated weapons,6 including drones and missiles, and in return, the Houthis allow Iran to extend its clout into the Red Sea, a vital link in a network of global waterways of great importance to the world economy.

Having seen how Tehran had institutionalized its influence in places like Lebanon and Iraq through local Shi’a proxies, the Saudis feared a similar Iranian outpost next door. To prevent that from happening, MBS launched a war against the Houthis, initially with the help of an Arab coalition from the Middle East and parts of North Africa. But he underestimated and ultimately failed to break his opponent, which remains in control of the bulk of Yemen’s northern highlands as well as the capital city of Sanaa. A mutually hurting military stalemate between the Houthis and Saudi-backed Yemeni forces led to a truce in April 2022 under the auspices of the United Nations.7 While the agreement expired in October 2022 after being extended twice, the cease-fire has largely held. Yet, notwithstanding this, the Houthis still have their heavy arms, which means that they continue to pose a security threat to Saudi Arabia.8

Diplomacy

Deterrence through diplomacy is as old a concept as the history of war among nations. It is a cheap tool, or at least much less costly than war, and, if properly utilized, it can be highly effective. The idea is simple: by talking with your adversary and attempting to manage or resolve your differences with them through bargaining and mutual concessions, you avoid war. Of course, the trick is how both parties get to a fair and sustainable “yes.” Diplomacy is also used to communicate to an adversary various information, including a state’s capacity and resolve to fight if pushed to it. Expert international relations scholarship suggests that deterrence can be achieved by conveying the information that a state is willing to fight over a disputed issue or issues.9

The Egypt-Israel war dynamic in the 1970s is a perfect example of the successful role of diplomacy in promoting peace. Egyptian President Anwar Sadat knew that countering the security threat from Israel and recovering the Sinai Peninsula, which Egypt had lost to Israel in the 1967 war, was not achievable solely through military means (nor through U.S. mediation alone). So, on Nov. 19, 1977, to the shock of both Israelis and Arabs, he went to Jerusalem, met with Israel’s leaders, and boldly declared “no more war” in the Israeli Knesset to reassure the Jewish state of Egypt’s peaceful intentions.10 Sadat’s gamble, for which he paid soon after with his life, facilitated an Egyptian-Israeli land-for-peace deal that culminated in a formal peace treaty in 1979.11

Can Saudi Arabia achieve lasting peace with Iran through a historic gesture like Sadat’s? This scenario should not be ruled out, but it is unlikely because the differences with the Egypt-Israel case are significant. Egypt and Israel felt mutually threatened and suffered a great deal from multiple wars they had fought. Each side genuinely feared aggression by the other, and both wanted an end to armed conflict. So, when Egyptian and Israeli leaders negotiated at Camp David with U.S. mediation, the conversations naturally were dominated by hard security matters.

Iran does not feel threatened by Saudi military capabilities or intentions. Indeed, Iranian leaders do not worry about the possibility of a Saudi attack against Iran, although they do worry about Saudi Arabia potentially providing a platform for U.S. and/or Israeli military operations against Iran (so a Saudi-Iranian diplomatic agreement that includes a commitment from the Saudis not to permit the use of their territory for third-party military operations would be valuable to the Iranians). Saudi Arabia, on the other hand, does feel threatened by Iran, for the simple fact that Iran has extensive military capabilities that it used offensively in September 2019, while its Houthi partners have launched hundreds of attacks from Yemen against Saudi Arabia.12

Riyadh is not the party from which the Iranians really want to extract security concessions. The number-one security worry of the Iranians is and always has been America’s military power in the region, followed by Israel’s, not the capabilities of the Saudis. It is the U.S. footprint Iran wants to reduce and ideally remove from the region.

This profound discrepancy in threat perceptions and objectives between Saudi Arabia and Iran does not make for a productive security dialogue. In the absence of symmetry on the issues and some level of mutual vulnerability, it is hard to see meaningful breakthroughs in a Saudi-Iranian dialogue.

Until recently, Riyadh had not engaged in formal negotiations with Tehran to address its security concerns. The Saudis had long held the view that talking with an adversary with a proven record of aggression and bad intentions was futile. When asked in February 2020 whether Saudi Arabia would enter into talks with Iran, Saudi Foreign Affairs Minister Faisal bin Farhan provided the same answer as many of his predecessors: “Our message to Iran is to change its behavior first before anything is to be discussed. […] Until we can talk about the real sources of that instability, talk is going to be unproductive.”13

But as it struggled to end its costly war in Yemen and as it watched the United States withdraw its combat troops from Iraq and Afghanistan and reduce its military involvement across the region, Saudi Arabia’s calculus on negotiations with Iran began to shift. A sense of urgency was building up in Riyadh. The Houthi rebels were not only mounting an effective resistance against the Saudi war effort but also attacking Saudi cities and airports, gravely damaging the image of a country that wants to be viewed as safe for business and foreign direct investment.

In April 2021, Saudi officials began to engage in talks with their Iranian counterparts in Baghdad about a range of issues, including, most notably, Tehran’s military support for the Houthis.14 The two sides reportedly met for five rounds over two years, and in March 2023, they announced a Chinese-sponsored accord to normalize their diplomatic relations (Saudi Arabia had cut off ties with Iran in January 2016, after Iranian protestors stormed Saudi diplomatic facilities in Tehran over the Saudis’ execution of dissident Saudi Shiite cleric Nimr al-Nimr).15

As of this writing, more than five months have passed since the Saudi-Iranian deal was signed, yet nobody knows what agreements, if any, Riyadh and Tehran have reached on security. There is language in the bilateral agreement on non-interference in the internal affairs of states in the region, but it is generic and non-binding.16 On Yemen, for example, it is not clear if Iran is legally committed to stopping its military aid to the Houthis, even though it allegedly agreed to halt covert weapons shipments to the Houthis as part of its diplomatic deal with Saudi Arabia.17 But in reality, it did not. In May 2023, U.S. Special Envoy for Yemen Tim Lenderking stated that Iran has continued to provide the Houthis with arms and drugs.18 The cease-fire to which the Houthis and Saudi Arabia agreed in April 2022 has held so far, but it could be broken at any moment if the Houthis decide to expand their territorial control.19 And even if Iran had a role in facilitating the truce, it is unclear if it can stop the Houthis from launching new attacks against Saudi civilian targets.

Saudi Arabia’s central demand from rapprochement with Iran is to stop further attacks against the kingdom, either directly or through regional surrogates. Iran, for its part, wants money from Saudi Arabia to alleviate its deep economic troubles. Indeed, Iran seeks Saudi and possibly Gulf Arab funds to support an economy that has been a source of widespread social unrest (the Saudis said they might invest in Iran but only under the right circumstances).20 Iran also wants Saudi Arabia to step back from funding anti-Iranian media networks and to readmit its ally, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, into the Arab League, which Riyadh did.21

While luring Tehran with normalization, economic investments, and diplomatic acceptance of the Assad government might bring temporary calm, it is unlikely to transform the strategic environment or eliminate Saudi fears of Iran. This Saudi strategy smacks more of appeasement than effective diplomacy. The success of Saudi deterrence cannot just be viewed as the absence of Iranian aggression. If the latter is avoided at the price of unilateral Saudi concessions and carrots, then it must be concluded that Saudi Arabia has built very little deterrence.

There are reasons to be less hopeful about the longevity of the current calm between Saudi Arabia and Iran. First, it is unlikely that Iran will sever its military links with the Houthis because that would deny it a strategic foothold on the Bab el-Mandeb strait, a critical global maritime chokepoint that controls access to the Red Sea.22 So long as the Houthis have Iranian weapons that can hit targets deep inside Saudi Arabia, Saudi security will be at risk.

Second, it is even more unlikely that Iran will stop seizing commercial tankers in Gulf waters because it sees its actions as a response to the United States occasionally confiscating cargos of Iranian oil.

Third, it is doubtful that Iran will quit supporting its militant allies in Lebanon and Iraq and suddenly respect the sovereignty of these countries. This would be vastly inconsistent with Iranian ideology and decades of foreign policy practice in the Arab world.

Fourth, the dispute between Saudi Arabia and Kuwait on the one hand, and Iran on the other, over the offshore Durra natural gas field has the potential to escalate.23 The Kuwaitis have said they and the Saudis exclusively own the natural wealth in the Gulf’s maritime “Divided Area,” while the Iranians have claimed they have a stake in it and called a Saudi-Kuwaiti agreement signed last year to develop it “illegal.”

External Protection

Saudi Arabia is not oblivious to the limits of diplomacy with Iran, which is why it has not put all its eggs in one basket to achieve deterrence against its archrival. Saudi Arabia could obtain official security guarantees from an external ally to prevent Iran from attacking it again. The two candidates that could play that role are the United States and possibly China.

Despite its so-called mediation of the Saudi-Iranian normalization deal, however, China is unlikely to commit to taming Iran because it has no interest in having significant security responsibilities in the region (it was the Saudis and the Iranians who did the heavy lifting on the deal, and they turned to Beijing to provide a great power venue and serve as a soft guarantor).24 There is also nothing in the Saudi-Iranian accord that requires Beijing to play a policing or monitoring role should either side make transgressions.

China will not choose between Saudi Arabia and Iran, because it relies on both for substantial oil imports. China and Iran are also strategic partners (although it is unclear what the real terms of that partnership are). Therefore, it is hard to imagine China agreeing to formally ally with Saudi Arabia and provide it with protection against Iran. To meet its ends in the region, Beijing is more likely to keep utilizing economics and lately some measure of diplomacy.25

Yet even if one assumes that China’s strategic calculus changes down the road, and the Chinese leadership considers extending a formal deterrent to Saudi Arabia to safeguard its long-term economic interests, the People’s Liberation Army will not have significant military capabilities, access, or basing in the region anytime soon to be able to play that guardianship role. China’s military strategy focuses on modernizing and developing capabilities for a high-end, short-duration fight in the Indo-Pacific, including technologically advanced missiles, stealth aircraft, naval vessels, submarines, and other hardware. While China can currently use these capabilities closer to home, it faces shortfalls in joint operations, tactics, sustainment, and deployment of these assets globally.

If Saudi Arabia’s chances of securing a credible defense pact from China are not good, the likelihood of getting it from the United States is not significantly better. But that is not for lack of trying. In return for potentially normalizing its ties with Israel, Saudi Arabia has asked for official security guarantees from Washington — which would amount to a formal extended deterrent — and help with establishing a domestic civilian nuclear program.26

President Joe Biden is unsure about this quid pro quo, saying in a July 9, 2023, CNN interview that this discussion is premature. In his recent interview with New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman, Biden was also hesitant about the Saudi deal when asked about it.27

For a while, the Biden administration was reportedly willing to entertain Saudi Arabia’s demands. Biden had dispatched his chief diplomat and top national security aides to the kingdom in recent weeks and months to discuss that very proposal. Even Biden’s political opponents support the idea. “I believe the Republican Party, writ large, would be glad to work with President Biden to change the relationship between the U.S. and Saudi Arabia,” said Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham after he and several of his colleagues recently met with MBS in Saudi Arabia.28

In theory, a Saudi-Israeli normalization deal could contribute to Middle East security and economic prosperity in the region, from which the United States and the world would benefit. But Biden, the commander-in-chief who decides on this issue (with ultimate Congressional authorization), made it sound like Washington is not willing anytime soon to pay the hefty price of an official defense pact with the kingdom to support a vision that only indirectly matters to the U.S. national interest. It is also hard to envision a scenario where the Pentagon and the broader U.S. national security community fully cooperate with the idea of obligating the United States to commit more military resources to the Middle East when the U.S. National Security Strategy and the U.S. National Defense Strategy are screaming for a greater U.S. focus on China’s potential seizure of Taiwan and Russia’s current war against Ukraine.

There are a few other concerns that are most probably on the minds of U.S. national security officials. First, if Iran avoids direct military action against Saudi Arabia (thanks to a U.S.-Saudi defense pact), but continues to operate in the gray zone and steps up its destabilizing activities against the kingdom through its regional proxies, how would Washington respond? More specifically, if the truce between Saudi Arabia and the pro-Iran Houthis breaks (and it’s possible it will as a result of Iran’s objection to Saudi-Israel normalization), and Saudi civilian targets are attacked again by the Houthis with Iranian weapons, would that trigger a U.S. military response against Iran, or against the Houthis? And more broadly, is the United States willing to go to war against Iran for Saudi Arabia? Washington will have no easy answers to these questions but Riyadh will expect them.

Second, a defense pact could deepen Saudi Arabia’s security dependency on Washington and impede necessary defense reforms. One of Washington’s wishes in relation to its Arab regional partners is for them to build their own military capabilities so they can better protect themselves and share the burden of regional security. If Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen is any indication, its war-fighting capabilities are suspect and in need of massive reforms. It is likely, though not inevitable, that a defense pact with Washington could delay, and even interrupt, those important reforms.

Third, a defense pact with Saudi Arabia could challenge security relations with Israel, Egypt, and the UAE. Washington would have to explain to these traditional regional partners, and to Taiwan and Ukraine, why they would be left out. It could extend similar security commitments to them, but all at the risk of U.S. military overstretch in the region and across the globe.

Saudi Arabia on April 16, 2018. Photo by BANDAR ALGALOUD / SAUDI KINGDOM COUNCIL / HANDOUT/Anadolu.

More Effective Military Capabilities

Regardless of the promise (or not) of diplomacy with Iran, and of the possibility of acquiring external protection, there is no substitute for domestic self-defense and deterrent capabilities. That is the first rule of survival in international relations, especially in dangerous environments such as the Middle East. Saudi officials must prioritize greater self-reliance and develop, both domestically and in cooperation with international partners, more effective military capabilities to deter Iran. And to some extent, they are.

No Saudi leader since the kingdom’s founding in 1932 has been more determined to overhaul the Saudi defense establishment and armed forces than MBS. Whether he will succeed, or whether he is biting off more than he can chew, is a separate matter, but the vision, the plan, and the effort are all there.

The challenge with Saudi defense transformation, like any other such process elsewhere, is that because it is all-inclusive, it will take many years before it has an appreciable impact on national defense. The Saudis are not just buying new military equipment, like they used to do to little effect on security. They are investing in rules, norms, processes, and procedures that make up a sound defense foundation — things they never did before. They are learning how to create and manage human resource systems; how to perform better budgeting and accounting; how to reduce waste and corruption; how to run logistics; how to formulate strategies and doctrine; how to establish chains of command; how to train more effectively; how to promote jointness; how to build professional intelligence systems; how to conduct planning; and how to properly do acquisition. They are essentially trying to achieve what is probably the most difficult task of any aspiring military power: convert their (healthy) defense budget into real combat power. And they are realizing that accomplishing that requires defense institutional reengineering that goes hand in hand with significant changes in Saudi culture and society. Indeed, as Vision 2030 correctly captures, it is all interconnected. Building a new Saudi military requires building a new Saudi society and a new Saudi economy. That, in a nutshell, is what MBS’s grand plan is all about.

But vision is not deterrence. Saudi Arabia lives next to a hostile and expansionist Iranian neighbor. It needs stronger self-defense and deterrence capabilities now. It cannot wait years for this vast defense reform process to bear fruit, and that is assuming it does. Riyadh’s options are not superior because there is currently little, if anything, in the Saudi military arsenal that could serve as a powerful deterrent against Iran. Even though the Royal Saudi Air Force is modern, the best unit in the Saudi military, and more experienced now due to its extensive involvement in Yemen, it is less likely to serve as a strong deterrent because it is not trained for long-range offensive operations in contested airspaces against well-defended targets (Iran’s air-defense network is dense and formidable). In short, the Royal Saudi Air Force is not a capable strike force.

There is one option, however, that could in the short term enhance the Saudi deterrent posture: escalating the development of ballistic missile capabilities. This option’s effectiveness is uncertain, though. It is also loaded with risks and will almost certainly come with costs — both reputational and tangible. But it is one the Saudi leadership seems determined to pursue. The logic, compelling or not, is that having enough ballistic missiles aimed at Tehran might deter the Iranian leadership from launching attacks against the Saudi homeland. Instead of relying exclusively on missile defense, which is costly and imperfect (though the kingdom has gained considerable experience in missile defense over the past few years due to its war in Yemen), the Saudis would threaten fire with fire and build an offensive missile deterrent of their own.

In 2019, U.S. intelligence agencies first learned that Saudi Arabia was collaborating with China to advance its ballistic missile program, which began in the late 1980s, when Riyadh purchased a modest number of ballistic missiles from Beijing. Satellite imagery obtained by CNN and the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies in 2021 of a site 200 kilometers west of Riyadh suggest that Saudi Arabia is producing solid-fueled ballistic missiles. Signs of a “burn pit” — used to dispose of solid-propellant leftover from the production line — is further evidence of domestic missile development.29 If Iran were to race to the bomb and Saudi Arabia were to follow suit, ballistic missiles would provide both with a delivery vehicle.

Whether Saudi Arabia’s acceleration of its ballistic missile program with Chinese help will deter Iran from launching another attack is highly uncertain. Deterrence is notoriously hard to understand and assess, especially among adversaries whose channels of communication are highly imperfect. Iran is extra sensitive to missiles as a result of its horrible experience with Iraq during the 1980-88 war.30 So, it might be deterred by Saudi Arabia’s missiles, or it might launch preemptive strikes to eliminate the threat.

Saudi Arabia's Deterrence Options

| Probability | Effectiveness | Risks | Costs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diplomacy | (status quo) | High in short term, Uncertain in long term |

Moderate | Low |

| External Protection | Low | Mid-to-high | Moderate | Low |

| Military Capabilities | Uncertain | Uncertain | Low | Moderate |

Mutually-Reinforcing Options

Diplomacy, Saudi or otherwise, is typically more effective if it is backed by powerful military capabilities and the credible threat of the use of force. Indeed, the right mix of carrots and sticks can be a sturdy companion to one state’s negotiations with another. As brilliant and powerful as Sadat’s diplomatic approach toward Israel was, it might not have worked had Cairo not displayed much improved military effectiveness during the 1973 war.

Riyadh does not have robust sticks yet, and its performance in the Yemen war does not strike fear into the heart of Iran. But Riyadh is developing deterrents both in the short term (ballistic missiles) and the long term (stronger overall combat power). However, Iran must believe that Saudi Arabia is not only able but also willing to use force if attacked. Saudi Arabia’s reputation for resolve is uncertain. On the one hand, Riyadh has been at war in Yemen for eight years, which is longer than any time it has fought in its history. On the other, it has shown lately that it is increasingly willing to extricate itself from the conflict even at the price of Houthi control of much of Yemen.

Should the Saudis create a ballistic missile force that roughly matches not necessarily the size but the lethality and range of that of the Iranians — and they can because they have the resources and the access to Chinese technology and assistance — they could push the Iranians to enter into arms control talks. This was a classic action-reaction dynamic during the Cold War between the superpowers. After the 1960s, whenever the Americans or the Soviets acquired a new weapon system (or were merely in the process of developing one) that threatened or was perceived to threaten strategic stability, the two sides engaged in arms limitations negotiations. This process led to several legally binding agreements, including the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty and the 1987 Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. The nuclear dimension of the superpower rivalry and the fear of mutual annihilation certainly played a role in facilitating arms control talks. So achieving similar negotiating outcomes in the conventional realm between Saudi Arabia and Iran will be incredibly difficult but not impossible.

The Saudi ballistic missile deterrent option could have mixed effects on the possibility of securing U.S. protection (the possibility of China selling an extended deterrent to Saudi Arabia is, as argued above, rather slim in the foreseeable future, so it is not worth entertaining seriously). If Saudi Arabia proliferates such a deadly and destabilizing weapon, it will not win hearts and minds in Washington. Nor will closer collaboration with China on defense. However, because the United States is deeply concerned about a missile arms race in the Middle East that could turn nuclear if both Iran and Saudi Arabia get the bomb, it might more carefully consider extending a defense pact to the kingdom to prevent it from proliferating. An expanded ballistic missile program in the hands of the Saudis indeed could serve as a bargaining chip with Washington.

Washington’s Options

Saudi Arabia’s deterrence options against Iran are not great, but Washington’s options for preventing Saudi Arabia from pursuing them are worse. So long as the United States has (legitimate) concerns about providing Riyadh with a formal defense pact, the Saudi leadership will use any means necessary to achieve a deterrent against Iran.

Washington may not be able to stop Saudi Arabia from proliferating and acquiring more powerful ballistic missiles, but it can help Riyadh develop its other military capabilities. That will arguably require a whole new approach of security cooperation between the two countries, one that develops a more coordinated blueprint for security, focusing on the kingdom’s ongoing defense restructuring project, conducting joint U.S.-Saudi contingency planning, and investing in all the institutional requirements of a competent defense apparatus that go beyond military equipment.31

Another U.S. option, should a more powerful Saudi ballistic missile capability become a fait accompli, is to push for regional arms control negotiations to try to stem an arms race. The last time the United States was involved in such multilateral diplomacy in the region was in the early-to-mid-1990s after the Madrid peace process.32 The Arms Control and Regional Security talks did not achieve strategic outcomes, but to even start them, U.S. leadership was required. Whether the United States can muster that leadership today in a region that has decreased in strategic importance in the eyes of many in Washington is vastly uncertain.

Bilal Y. Saab is a senior fellow and director of the Defense and Security Program at MEI.

Top right-side photo: A ceremony marking the 50th anniversary of the creation of the King Faisal Air Academy and its 91st term graduation is held at King Salman airbase in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, on Jan. 25, 2017.

Endnotes

1 Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, GOV.SA.

2 Ben Hubbard, Palko Karasz, and Stanley Reed, “Two Major Saudi Oil Installations Hit by Drone Strike, and U.S. Blames Iran,” The New York Times, Sept. 14, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/14/world/middleeast/saudi-arabia-refine….

3 Scott Neuman, Bill Chappell, and Richard Gonzales, “Attack on Saudi oil facilities makes oil prices spike,” NPR, Sept. 16, 2019, https://www.npr.org/2019/09/16/761118726/oil-prices-jump-following-dron….

4 Bruce Riedel and Bilal Y. Saab, “Al Qaeda’s Third Front: Saudi Arabia,” The Washington Quarterly, Vol. 31, No. 2 (Spring 2008), pp. 33-46, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/spring_al_qaeda_ri….

5 Mohammed Ghobari, “Houthis tighten grip on Yemen capital after swift capture, power-sharing deal,” Reuters, Sept. 22, 2014, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security/houthis-tighten-grip-….

6 Michelle Nichols and Jonathan Landay, “Iran provides Yemen’s Houthis ‘lethal’ support, U.S. official says,” Reuters, April 21, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security-usa/iran-provides-yem….

7 Mostafa Salem and Lianne Kolirin, “Saudi-led coalition and Houthis agree on truce in Yemen, raising hopes for the 'start of a better future,'” CNN, April 1, 2022, https://www.cnn.com/2022/04/01/middleeast/yemen-truce-un-intl/index.html.

8 Mohammed Alghobari and Reyam Mokhashef, “Yemen truce expires as U.N. keeps pushing for broader deal,” Reuters, Oct. 3, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/yemen-truce-expires-un-keeps-….

9 Anne E. Sartori, Deterrence by Diplomacy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998), https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691134000/deterrence-by….

10 HDS Greenway, “Sadat, Begin Pledge 'No War,'” The Washington Post, Nov. 22, 1977, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1977/11/22/sadat-begin-….

11 “Milestones: 1977–1980: Camp David Accords and the Arab-Israeli Peace Process,” Office of the Historian, U.S. Department of State, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1977-1980/camp-david.

12 Tim Lister and Nic Robertson, “Source: ‘High probability’ Saudi attack launched from Iranian base near Iraq,” CNN, Sept. 17, 2019, https://www.cnn.com/2019/09/17/middleeast/saudi-attack-iran-base-intl/i….

13 John Irish, “Iran must change behaviour before any talks - Saudi minister,” Reuters, Feb. 15, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-germany-security-saudi-iran/iran-mus….

14 Raya Jalabi, Aziz E. Yaakoubi, and Ghaida Ghantous, “Saudi confirms first round of talks with new Iranian government,” Reuters, Oct. 3, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/saudi-confirms-first-round-ta….

15 Mohammad Ali Shabani, “Inside the talks between Iran and Saudi Arabia,” Axios, April 27, 2022, https://www.axios.com/2022/04/27/iran-saudi-arabia-hold-talks.

16 Parisa Hafezi, Nayera Abdallah, and Aziz E. Yaakoubi, “Iran and Saudi Arabia agree to resume ties in talks brokered by China,” Reuters, March 10, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/iran-saudi-arabia-agree-resum….

17 Dion Nissenbaum, Summer Said, and Benoit Faucon, “Iran agrees to stop arming Houthis in Yemen as part of pact with Saudi Arabia,” The Wall Street Journal, March 16, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/articles/iran-agrees-to-stop-arming-houthis-in-yeme….

18 Jonathan Landay and Doina Chiacu, “Iran still smuggling weapons, narcotics to Yemen, U.S. envoy says,” Reuters, May 11, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/iran-continues-smuggle-weapon….

19 “The Secretary-General -- Remarks to the media on a nationwide truce in Yemen, New York,” Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary General for Yemen, United Nations, April 2, 2022, https://osesgy.unmissions.org/secretary-general-remarks-media-nationwid….

20 Natasha Turak, “Saudi Arabia could start investing in Iran 'very quickly,' finance minister Mohammed Al-Jadaan says,” CNBC, March 15, 2023, https://www.cnbc.com/2023/03/15/saudi-arabia-could-invest-in-iran-very-….

21 Aidan Lewis and Sarah E. Safty, “Arab League readmits Syria as relations with Assad normalize,” Reuters, May 7, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/arab-league-set-readmit-syria….

22 Justine Barden, “The Bab el-Mandeb Strait is a strategic route for oil and natural gas shipments,” U.S. Energy Information Administration, Aug. 27, 2019, https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=41073.

23 Hatem Maher, Muhammad Al Gebaly, Hugh Lawson, and Leslie Adler, “Kuwait, Saudi Arabia have 'exclusive rights' in Durra gas field, Kuwait oil minister says,” Reuters, July 10, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/kuwait-saudi-arabia-have-exclus….

24 Mostafa Salem, Adam Pourahmadi, and Nadeen Ebrahim, “Archrivals Iran and Saudi Arabia agree to end years of hostilities in deal mediated by China,” CNN, March 10, 2023, https://www.cnn.com/2023/03/10/middleeast/saudi-iran-resume-ties-intl/i….

25 Bilal Y. Saab and Melissa Horvath, “Should the US be wary of Chinese military power in the Middle East?” Al Majalla, June 14, 2023, https://en.majalla.com/node/293496/politics/should-us-be-wary-chinese-m….

26 Michael Crowley, Vivian Nereim, and Patrick Kingsley, “Saudi Arabia Offers Its Price to Normalize Relations With Israel,” The New York Times, March 9, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/09/us/politics/saudi-arabia-israel-unit….

27 Thomas L. Friedman, “Opinion | Biden is Weighing a Big Middle East Deal,” The New York Times, July 27, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/27/opinion/israel-saudi-arabia-biden.ht….

28 Barak Ravid, “Biden admin pushing for Saudi-Israeli peace deal by end of year, officials say,” Axios, May 17, 2023, https://www.axios.com/2023/05/17/saudi-arabia-israel-peace-normalizatio….

29 Zachary Cohen, “CNN Exclusive: US intel and satellite images show Saudi Arabia is now building its own ballistic missiles with help of China,” CNN, Dec. 23, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/12/23/politics/saudi-ballistic-missiles-china/….

30 Jason Rezaian, “An ally of Syria, Iran also bears scars from chemical weapons attacks — by Iraq,” The Washington Post, Sept. 12, 2013, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/an-ally-of-syria-iran-….

31 Bilal Y. Saab, “After Oil-for-Security: A Blueprint for Resetting US-Saudi Security Relations,” The Middle East Institute, Feb. 17, 2023, https://www.mei.edu/publications/after-oil-security-blueprint-resetting….

32 “Milestones: 1989–1992: The Madrid Conference, 1991,” Office of the Historian, U.S. Department of State, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1989-1992/madrid-conference.