Summary

Less than 10 years after seizing power in Yemen, the Iran-backed Houthi militia continues to evolve — and so do the threats emanating from it. After several years of negotiations, it now seems likely that the Houthis and Saudis will reach a peace agreement, and it is worth considering how such a deal could change the group’s trajectory. This report examines a number of possible futures that could develop in Yemen over the next 1-2 years based on shifting capabilities, interests, and alliances.

Executive Summary

Less than 10 years after seizing power in Yemen, the Iran-backed Houthi militia continues to evolve — and so do the threats emanating from it. Since the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas war in October 2023, the group has launched hundreds of rockets and missiles against international shipping in the Red Sea and at the Israeli port city of Eilat. These attacks have significantly impacted the global economy, and have led to a rise in prices for certain consumer goods in the Middle East and Europe.

In the Yemeni civil war, the Houthis combined advanced military capabilities provided by Iran with aggressive media operations in order to fight the Saudi-led coalition to a standstill. After several years of negotiations, it now seems likely that the Houthis and Saudis will reach a peace agreement that will provide the Houthis with a much-needed influx of funds and the Saudis with much-sought-after quiet along the kingdom’s southern border.

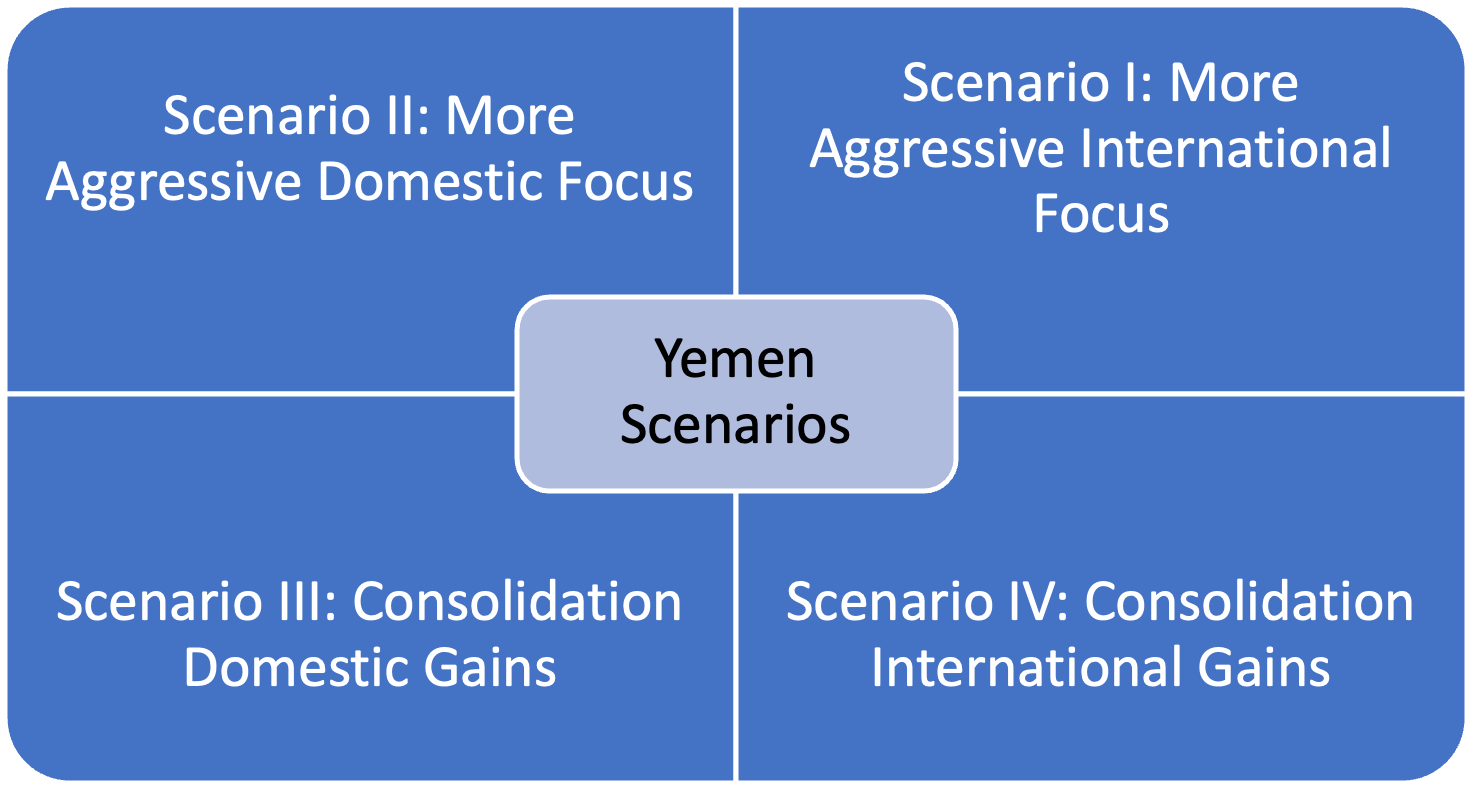

Yet, given that Houthi rhetoric and objectives have largely been defined over the past decade by opposition to the Saudi-led coalition, it is worth considering how an impending Houthi-Saudi peace deal could change the group’s trajectory. This report examines a number of possible futures that could develop in Yemen over the next 1-2 years based on shifting capabilities, interests, and alliances. They have been constructed on the basis of a 2x2 matrix that considers potential Houthi paths forward, using aggression vs. consolidation as the Y-axis and international focus vs. local focus as the X-axis. Some of the report’s conclusions include:

-

While the Houthis are unlikely to alter their long-term ideological objectives, it is possible that their priorities and methods will shift as a result of a changing strategic environment.

-

Certain changes in Houthi behavior may be identified as opportunities for engagement, but this is more likely wishful thinking or a ruse than an actual shift away from the dangerous and destructive policies of the “Axis of Resistance.”

-

It is possible that the Houthis will seek to harness their international “success” (vis-à-vis international shipping and Israel) to make gains in the domestic arena, as the latter realm has been a higher priority for much of the past decade. Yet one cannot discount the possibility that the group is experiencing a sense of euphoria from the success of its initial international foray, which will push it toward further international escalation — and potentially miscalculation.

-

The task of containing the Houthis will likely fall to the U.S. and its allies, while great power rivals like Russia and China may seek to harness rather than oppose the group’s destructive activities.

targeted by Houthi forces in international waters in the Red Sea on March 3, 2024. Photo by Al-Joumhouriah channel via Getty Images.

Introduction

For around four years now, Saudi Arabia has been looking for an elegant exit from the Yemeni civil war. This is, in large part, because fighting in Yemen has dragged on and proved far more costly than Riyadh initially anticipated1 when, in 2015, it led a coalition to restore the internationally recognized government of President Abed Rabbo Mansour Hadi and roll back advances by the Iran-backed Houthi militia. Now that a peace agreement between Saudi Arabia and the Houthis appears imminent, if temporarily delayed due to the ongoing Houthi attacks on international shipping in the Red Sea, it is worth considering the potential scenarios and implications that could result from such a deal.2

Though the battlefield in Yemen has been at a stalemate since around 2018, the Saudis only accelerated their efforts to extricate themselves from the conflict in 2020 to ensure a softer landing in the event that Joe Biden was elected president of the United States.3 While President Donald Trump did not seem to have a problem with Saudi Arabia’s involvement in Yemen, and even designated the Houthis as a foreign terrorist organization,4 Biden made a campaign promise to isolate Saudi Arabia and then went on to delist the Houthis early in his tenure.5 Rather than creating the conditions conducive to an agreement, Biden’s pressure on Saudi Arabia and soft touch with the Houthis prompted the latter to escalate in 2021.6

Since 2022, the two sides have reduced the intensity of the fighting and managed to maintain an imperfectly enforced (and at times unofficial) Saudi-Houthi cease-fire. The Saudis, realizing that time is working against them as they have far more to lose than the Houthis as the conflict drags on, have made major gestures to convert this cease-fire into a long-term truce.7 The basic outlines of such an agreement would be Riyadh ceasing all direct involvement in Yemen, which includes removing restrictions on air travel from Sana’a and activity in Houthi ports, and compensating the Houthis for “damages” suffered during the war; in turn, the Houthis would commit to respecting Riyadh’s sovereignty, meaning no more cross-border attacks, and to engaging in a political process aimed at reaching a peace agreement with the other parties involved in Yemen’s civil war.

It is worth noting that any deal between Saudi Arabia and the Houthis will not be made on an equal footing. The imbalance has been evident from the start of the negotiation process, throughout which Saudi Arabia has made numerous gestures to the Houthis, including allowing senior members of the group to enter Saudi Arabia to participate in the Hajj.8 Meanwhile, the Houthis have only increased their demands without making any concessions of their own — as is their long-established negotiating practice. It is unlikely that any deal between the parties will hold indefinitely, and it will likely be the basis for ongoing negotiations in which each side seeks to improve its positioning. In addition to considering the initial terms of such an agreement, it is also worth thinking about how each party intends to use the time and resources it buys them.

The Houthis are unquestionably hostile to the United States and Israel, but it is important to note that despite having the capabilities to do so for some time,9 they only opened the “Israeli front” nearly a decade after they seized Yemen’s capital. The group has stated unequivocally that it seeks the destruction of both the US and Israel since 2002, when it adopted a slogan, known as “the scream,” which calls for “death to America” and “death to Israel.” The Houthis also noted in 2019 that they have a bank of military targets in Israel and the capabilities to hit them.10

Following Hamas’ surprise attack on Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, the Houthis have joined other members of Iran’s so-called “Axis of Resistance” in the multi-front conflict and launched strikes on Israeli territory with long-range missiles and drones, nearly all of which have either fallen short or been neutralized.11 In addition, the Houthis have also harassed maritime traffic in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden, claiming that they are only targeting ships with connections to Israel but, in practice, taking pot shots without much effort to distinguish Israel-connected shipping from other international maritime traffic.12 As the Red Sea is one of the key waterways for global commercial shipping, handling an estimated 30% of container traffic,13 the West has stood up an alliance that has targeted Houthi capabilities to prevent the group from launching additional attacks; the extent to which this effort will succeed in degrading its capabilities and deterring it from additional attacks does not initially appear promising.14

Four scenarios that consider outcomes of a Saudi-Houthi agreement are presented here and are designed to help decisionmakers think about and prepare for a range of possibilities. They have been constructed on the basis of a 2x2 matrix that considers potential Houthi paths forward and uses aggression vs. consolidation as the Y-axis and international focus vs. local focus as the X-axis. The scenarios are based on the working assumptions that Israel’s conflict with Hamas will continue for some time and that any Houthi-Saudi agreement reached is unlikely to be formally scuttled by the Saudis even in the event of Houthi violations. The timeline for the developments laid out below is the upcoming 1-2 years (2024-2025). To be clear, these scenarios are not designed to predict the future, but to consider a range of reasonable possibilities for how events could unfold.

Scenarios

I. More Aggressive International Focus: “Houthis Go Global”

After the Houthis ink a deal with Saudi Arabia, they use much of the funding that comes in for payment of salaries and “reconstruction” to enhance and expand their military capacity. Houthi leader Abdul-Malek al-Houthi delivers a speech declaring that if the group could defeat the Saudi military, which pours tens of billions of dollars per year into defense, on a shoestring budget, then Yemenis should imagine what the Houthis could accomplish with this increased investment. The Houthis invest in underground infrastructure in the mountainous areas of northern Yemen designed to house their rocket, missile, and drone production and storage facilities.

Saudi Arabia seeks to exercise some control to prevent the “compensation” from being diverted toward the Houthi military budget, but the Houthis’ stranglehold on the economy in areas under their control prevents Riyadh from achieving much in that regard. In addition to the weapons and training provided by Iran, the Houthis pay for experienced mercenaries from Russia and North Korea to professionalize their army.

While doing so, the Houthis largely abide by their commitments to Riyadh. However, they continue to target their external “enemies” transiting the Red Sea as well as Western (American, British, French, and Israeli) assets in the region. Israel’s refusal to lift the “siege” on Gaza even after the fighting ends is the reason the Houthis give when they claim that they cannot end their Red Sea campaign, which symbolizes Yemeni solidarity with the Palestinian cause. The Houthis also warn Saudi Arabia to avoid establishing relations with Israel as they would consider this a hostile act that threatens Yemen’s national security and requires a military response; the Saudis abide by this while maintaining the impression in Washington that they are still interested in normalization.

The Western response is largely symbolic and reactive. Out of concern for the humanitarian situation in Yemen, the fragile Saudi-Houthi agreement, and the desire to avoid getting drawn into another Middle Eastern quagmire, the US and its allies only respond kinetically when a Houthi attack results in loss of life.

International shipping remains wary of the Red Sea, with the exception of some Chinese companies that have reached a “financial understanding” with the Houthis that enables them to transit. This drives up prices of a variety of consumer goods in Europe and the Middle East and creates an additional revenue stream for the Houthis, who are therefore incentivized to continue. After failed efforts to rein the Houthis in via diplomatic pressure,15 Beijing sees paying them a “toll” for safe passage as the most realistic and cost-effective option to minimize the economic impact of Red Sea attacks, and this gives Chinese companies a leg up on their Western competition, which cannot pay off the Houthis due to their renewed terrorism designation.

Iran and China work together in secret to push the Houthis to test new anti-ship and surface-to-air missile technology on American-led forces in the Red Sea. While China is not pleased with the Houthi disruptions to international maritime commerce, it realizes that it is better off trying to exploit and control this development rather than seeking to reverse it. Beijing yields significant intelligence on US anti-missile and stealth capabilities that inform its anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) efforts in the Indo-Pacific.

The Houthis also establish outposts in Syria and Lebanon to open additional fronts with Israel. In reality, these “outposts” consist of dozens of Yemeni mercenaries hired by Hezbollah and Iran for $200 per month primarily to engage in Captagon smuggling throughout the region and occasionally to heat up the border areas with Israel by launching rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs) at Israeli patrols. Jordan is increasingly concerned that the Yemen problem is becoming a threat to its sovereignty and stability and cuts off the daily Sana’a-Amman flights that were restarted as part of the Saudi-Houthi agreement. The Houthis then turn up their rhetoric against Amman, insisting that it is part of the American-Zionist alliance and calling King Abdullah of Jordan an American stooge.

Analysis

-

Houthi engagement in the international arena may evolve over time but will likely remain confined to the realms of terrorist and criminal activity. A weak international response to Houthi provocations will encourage the group into thinking it has more leeway to exploit.

-

International shipping through the Red Sea could experience significant disruption for some time, and while the global economy may take a hit from that, it will also likely find a way to cope with the challenge.

-

China, Russia, and Iran may not be pleased with everything the Houthis do in the Red Sea and beyond, but they will likely try to influence Sana’a and harness developments for their advantage to the extent possible rather than confronting the group.

Sana’a, Yemen. Photo by Mohammed Hamoud/Getty Images.

II. More Aggressive Domestic Focus: “All Roads Lead to Marib”

Having made Yemen an international player by standing up to the US and Israel, Abdul-Malek decides to leverage those accomplishments for tangible benefits. International prestige is important, but it will not pay the salaries of Houthi soldiers or fund the spare parts for Houthi helicopters. Also, given the crushing poverty of Yemenis, the people under Houthi rule can only be “taxed” so much.

Therefore, the Houthis decide to utilize the widespread support in Yemen for their actions against Israel and the quiet along their northern border to launch a massive assault against the government of Yemen’s forces along the Marib front. The Saudis are alarmed by this development, but they are slow in formulating a response which could thread the needle by both denying the Houthis a victory and avoiding being dragged back into the Yemeni morass. Infighting within Yemen’s Presidential Leadership Council means that United Arab Emirates-backed forces do not answer the call to rescue the Saudi-backed governor of Marib from Houthi attacks. Marib defenses hold initially against the Houthi onslaught, but they ultimately succumb due to the lack of international air support targeting Houthi forces on the Yemeni plateau.

This is just the first push in a much larger Houthi campaign to take the rest of Yemen. It is not fully successful but manages to capture major assets, including the oil infrastructure in Marib. The Houthis’ immediate aim with this campaign is to squeeze money and resources out of the conquered areas.

In light of their newfound energy assets, the Houthis are approached by Chinese firm Anton Oil — a company familiar with operating in challenging environments such as Iraq.16 The Houthis agree to provide Anton with the rights to oversee the production and sales of energy in areas under their control on the basis of a secretive revenue-sharing agreement. However, whether by sabotage, graft, or incompetence, the Houthi-Anton joint venture does not manage to yield significant profits, and there are questions as to whether it is a viable endeavor.

The Saudis are deeply concerned by the fact that anti-Houthi forces in Yemen are collapsing, as Riyadh had banked on them being a significant check on the Houthi threat. After the fall of Marib, Yemen’s internationally recognized government becomes something of a fiction, while the Southern Transitional Council-affiliated forces operating under President Aidrous al-Zubaidi are all that stands in the way of complete Houthi domination of Yemen. As a last resort, the Saudis then join forces with the Emiratis to work on establishing a more unified and effective Yemeni opposition to Houthi expansionism.

South Yemen declares its secession from northern Yemen to begin building its forces as a legitimate government rather than simply as a militia. Several countries support the nascent state due to lobbying by the UAE and Saudi Arabia. Surprisingly, Iran supports this step as well, largely because of an awareness that doing so is a deathblow to the internationally recognized government of Yemen and this opens a door for the Houthis to be recognized as the legitimate rulers of northern Yemen.

South Yemen seeks to disconnect all of its infrastructure, including its monetary system and tax system, from northern Yemen. It creates a new currency, known as the South Arabian dinar, and pegs it to the US dollar to ensure its stability. South Yemen is not a Western democracy by any stretch, but it is far more tolerant and less totalitarian than the Houthi regime. The Emiratis and Saudis dedicate a great deal of resources to building small enclaves of success and good governance in the south that are meant to serve as a basis for replication.

As media outlets in Yemen warn of the impending humanitarian catastrophe, hundreds of millions of dollars of additional aid pours into Yemen, particularly the population centers under Sana’a’s control, and the Houthis are able to divert or exploit a large percentage of it. The Houthis blame American-Zionist treachery for the country’s economic collapse.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE are deeply concerned by the Houthi advance and its impact on regional stability, and they realize that their conciliatory approach has only emboldened the group. Using South Yemen as a forward operating base, the Saudis and Emiratis undertake major efforts to covertly subvert the Houthi regime — with the help of US advice and support. The thinking in Riyadh and Abu Dhabi is that even if these efforts do not immediately bring down the Houthi regime, which they consider a major strategic threat, it is necessary to keep Abdul-Malek preoccupied with putting out domestic fires so he stays out of the international arena.

Analysis

-

The Houthis may exploit their increased popularity from their attacks on Israel to take a more aggressive approach within Yemen.

-

The Houthis’ lack of familiarity with the international arena may cause them to miscalculate regarding external responses to their domestic activities.

-

As the Houthi threat grows, Saudi Arabia and the UAE may be forced to try to build international coalitions to counter the Houthis, including but not limited to realignment to close gaps between Riyadh and Abu Dhabi; it remains difficult to predict what such a shift would look like.

III. Consolidation of Domestic Gains: “Inevitable Division”

The senior Houthi leadership, including Abdul-Malek al-Houthi, Mohammed Abdel-Salam, Abdul-Karim al-Houthi, Ihsan al-Humran, Abu Ali al-Hakim, and Mahdi al-Mashat, all meet for a celebratory meal. They have accomplished more than they could have hoped for on the international stage. The Houthi military forces have proved that they can cause significant damage to the global economy, target Israel with long-range drones and missiles, launch direct attacks on the US military, and barely suffer any consequences for doing so. They have made all Yemenis, pro-Houthi and anti-Houthi alike, proud of Yemen’s bravery and strong stance ostensibly in support of Palestine.

In addition, after finally signing a peace agreement with Saudi Arabia, they are expecting an influx of funds. That is a major development for the Houthi organization, which has already squeezed its population for everything it is worth and was beginning to receive some pushback from the public. The group decides it is important to invest this money in strengthening its grip on the population in the territories under the Houthis’ control.

In part, this initiative involves increasing the payouts to tribal leaders who cooperate with Sana’a and provide it with a steady flow of conscripts. Some public-sector employees receive a minor disbursement that is meant to compensate them for years in which they were paid a small fraction, if any, of their salaries; this stops much of the public protests as the employees hope that there will be more to come as payments from Riyadh continue.

The Houthis take a moment of relative quiet on both the international and domestic fronts as an opportunity to eliminate any lingering remnants of opposition. They target remaining non-Houthi student organizations, fragments of political parties, and non-sanctioned religious study groups and imprison their most prominent members as traitors working with the US-led coalition. They also seize the assets of wealthy individuals who are viewed as not sufficiently supportive of the Houthi cause, under the pretense of corruption, and promise Yemenis that these assets will eventually be redistributed to the public.

Afterward, the Houthis’ domestic intelligence agencies are able to act more aggressively as they do not need to fear any outcry from the public or civil society. The testimonies of survivors of Houthi prisons indicate that they have created a torture-industrial complex comparable to that of Bashar al-Assad’s Syrian regime in terms of size and brutality. This terrifies the local population initially and over time creates a growing hostility toward the regime.

Israel understands from the group’s inward focus that the Houthi threat has largely subsided, and so Jerusalem resumes its focus on the two key remaining threats in the Iran-led axis: Hezbollah and Tehran’s nuclear program. Meanwhile, international shipping returns to the Red Sea as if nothing had happened, insurance rates return to their previous levels, and Western fleets redeploy from the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden. The US moves to sanction Yemen’s Houthis primarily for their human rights violations, including the use of child soldiers, sexual violence against women, and their imprisonment and torture of journalists.

The UAE, under pressure from Iran and China and with security guarantees from them, presses the forces under its influence in southern Yemen to engage with the Houthis in talks on the partition of Yemen. Saudi Arabia, concerned that it will be left without any channels of influence in its own “backyard,” seeks to cultivate deeper ties with the Houthis and pull them out of the Iranian orbit. While this strategy might have been feasible a decade ago, the Houthis’ prominent role in the Axis of Resistance makes this effort doomed to fail regardless of the amount of money that Saudi Arabia would be willing to spend on the issue.

Instead, Riyadh settles for repairing its relationship with Washington to shore up its defenses in anticipation of the possibility that the Houthis will once more “look outward” after they have partitioned Yemen. As a result, Washington pushes Saudi-Israeli cooperation forward and enables it to expand in terms of both substance and publicity; it does not yet reach full normalization so as to avoid provoking Houthi ire.

Analysis

-

The Yemenis under Houthi rule will likely chafe at the intensifying repression of the regime, but in the absence of an organized and well-armed opposition can do little to unseat the Houthis.

-

Continued frustration with the Houthis’ intransigence could push Riyadh to enhance defense ties with Washington, but fear of a Houthi response may create pressure to avoid normalization with Jerusalem.

-

If the Houthis focus more on domestic affairs, that may make external parties, including those involved in the conflict, more inclined to believe that it is possible to reach and maintain agreements with them.

IV. Consolidation of International Gains: “Saadah’s Statesman”

After making peace with the Saudis, the Houthis push Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman to allow them to establish a “coordination office” in the kingdom. With the end of the Yemen war in sight, the crown prince concedes and allows for a 10-person office in a non-descript house on the outskirts of Riyadh. The stated aim of this office is to maintain contact with the Saudi government and prevent any complications in the relationship from spiraling out of control.

But after demonstrating its military prowess and ability to inflict considerable damage on the global economy, Houthi Spokesman Mohammed Abdel-Salam believes the group’s position can be leveraged further. Abdel-Salam says that while the Houthis will continue to enforce a strict form of Islam domestically and that they will not tolerate dissent, they are open to developing ties around the world to avoid “misunderstandings” in the Red Sea. They point to their offices in Riyadh as proof of the group’s legitimacy and interest in developing international ties.

At the request of Iran, Russia allows the Houthis to open an office in Moscow. Likewise, the Syrian regime, having just expelled Houthi diplomats in October 2023,17 agrees to Iran’s request to allow the group to return. Surprisingly, some Mediterranean countries involved in Red Sea shipping also decide that it would be worth their while to open a dialogue with the group rather than simply ignoring them. Houthi offices are opened in Cyprus and Turkey, and the ships of those countries are spared the sporadic missile attacks taking place every few months in the Red Sea.

The expansion of the Houthis’ “diplomatic” representation provides the group with three main benefits. First, in the eyes of the Yemeni public, the regime can now claim international legitimacy, and this is a major blow to regime opponents. Second, as the group seeks to evade international sanctions, it is able to enhance its sanctions-busting network by placing its representatives abroad. Finally, as the group aspires to emulate the Hezbollah model, it is able to begin building terror infrastructure abroad that can be used to target dissidents, Israeli embassies, and American officials.

Washington assesses that the group has reached a turning point and that it is moderating as is evident by the appointment of a Western-educated spokesman who previously served in former President Ali Abdullah Saleh’s government. The Houthi rhetoric, at least in English, now appears much less aggressive and dangerous. The White House seeks to avoid returning the group to the list of foreign terrorist organizations and instead opts to establish channels of communication via Oman.

Given their focus on international events and the desire to avoid creating intense domestic pressure that could elicit a backlash, the group does not take any extreme steps to consolidate power at home in a manner that could alienate the Yemeni public. There are some efforts to develop the domestic economy according to principles of self-reliance, including grandiose mega-projects (at least by Yemeni standards) that are rightly assessed by outsiders to be vanity projects with little economic value, and which are unlikely to be completed.

During this time, the Houthis continue to work closely with Iran to establish domestic capabilities for weapons production, including but not limited to drones and missiles. Given the dismal economic outlook, the Houthis decide to enter the low-end arms market, competing with countries like North Korea as a willing supplier to rogue states and criminal enterprises. They also become a key surrogate for training and indoctrinating Iran-backed militias throughout the Middle East. Due to their ability to produce weapons and the relationships they cultivate with the militias they train, the Houthis are able to expand their influence and the threat they posed to Western interests. However, they opt to make this progress quietly and without much fanfare.

In parallel, Israel works to create a more hostile strategic environment for the Houthis. It builds relations with regional countries and organizations located in the Houthis’ vicinity to challenge their ability to operate and dominate nearby areas, particularly but not exclusively in the maritime space. These relationships do yield good results for Israel in terms of the collection of intelligence, which, in turn, enables it to operate more effectively to expose, disrupt, and degrade Houthi infrastructure.

Analysis

-

Houthi intentions may remain opaque and, therefore, it is essential to maintain a focus on degrading their capabilities.

-

The US, seeking to avoid another Middle Eastern war, may be inclined toward two complementary approaches: 1) a lower prioritization of the Yemen threat when compared with the views of its regional allies and 2) a more charitable interpretation of Houthi intentions when provided with plausible deniability.

-

It is unlikely that the Houthis’ overall intentions will change dramatically, and therefore periods of quiet should not be interpreted as shifts in strategic aims.

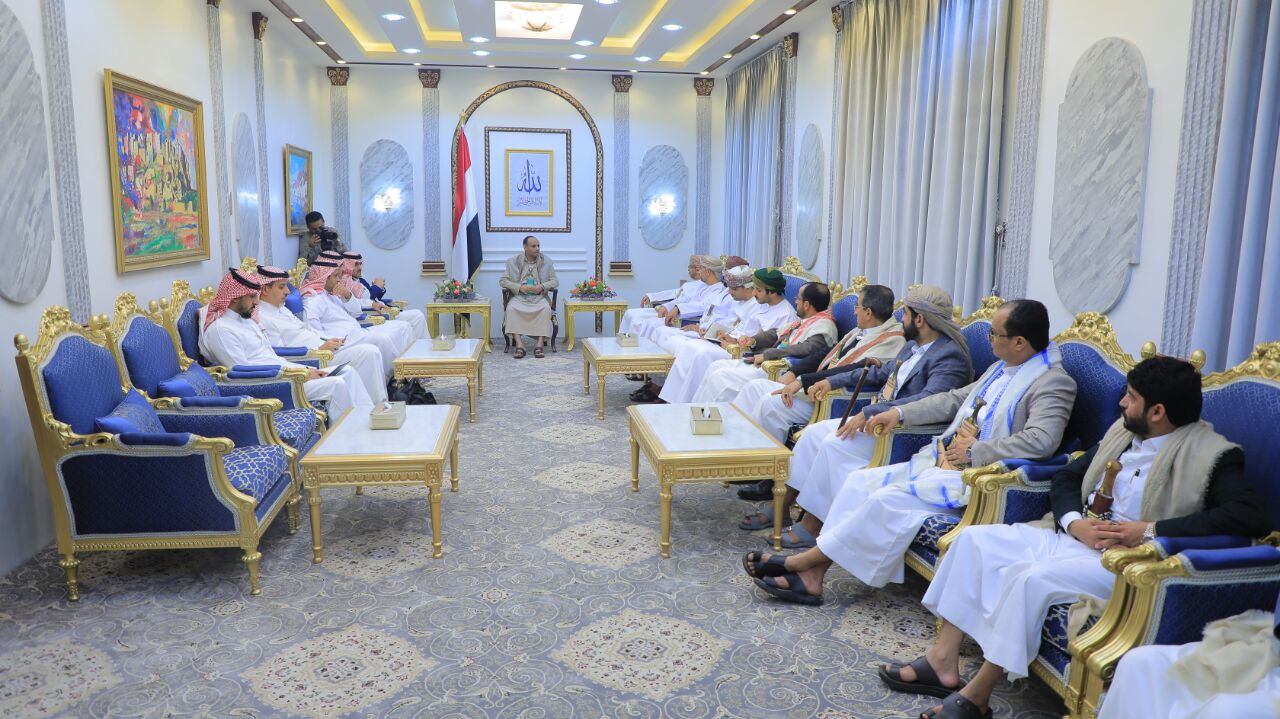

Houthi officials, on April 9, 2023, in Sana’a, Yemen. Photo Handout/Saba News Agency via Getty Images.

5 Key Points for Consideration

Based on the scenarios described above we can conclude five essential points that should be factored into any decision-making on the conflict:

-

Saudi Arabia will be managing a complex balancing act. On the one hand, Riyadh has no illusions about the dangerous nature of the Houthi regime. On the other hand, it is skeptical of Washington’s support and cannot militarily defeat the Houthis. Therefore, it can be expected to try to maximize the diplomatic channel with the Houthis to lower the flames of conflict to the extent possible while simultaneously shoring up its defense and seeking to prevent the group from growing more powerful. There will be constant tension between these two efforts.

It is unclear how the Houthis will react in the event that the Saudis make consequential foreign policy or national security policy decisions that conflict with their interests or ideology, such as expanding the US presence in the kingdom.

-

The Houthis perceive the international and domestic arenas as linked but separate. The domestic arena is and will likely remain the priority as it is both more familiar to the group and more essential for its survival. Houthi activities abroad will likely be used to serve the group’s domestic aims but are ripe for miscalculation, even with counseling from the more experienced Iranian and Hezbollah wings of the Axis of Resistance.

-

Maritime traffic in the Red Sea may be reduced for an extended period. The Houthis have the capability to cause disruptions in a variety of different ways, including low-tech means, and can claim that this is targeted at Israel even in instances that do not involve it. This is a way to capture international attention and requires a great deal of resources from the international community to defend against. However, if this leverage is overused then it could either elicit an overly powerful response or encourage the international community to create workarounds that reduce its impact.

-

Yemen’s internal dynamics remain fluid but not completely so, as they have hardened to a degree. While each of the actors will pursue its own interests in most cases, it appears highly unlikely that tectonic shifts such as a Houthi defection to the Saudi-led coalition is in the cards. Even if Riyadh can offer the Houthis more money than Tehran, the Houthis will likely view the two relationships as complementary rather than competing: inviting arms and training from Iran to squeeze funds out of Saudi Arabia. Sana’a is now a member of the Axis of Resistance and will likely remain that way.

However, the possibility of withdrawal of Saudi support from the internationally recognized government of Yemen following a Saudi-Houthi agreement may lead coalition forces to realign in unexpected ways.

-

Houthi threats to the US and its allies are likely to evolve rather than disappear. At present, the Houthis have demonstrated their ability to target US allies with long-range weaponry and international shipping with a variety of means, but the Houthi threat is unlikely to remain static. The group’s ambitions presumably include targeting Israeli and American assets abroad, and in the future they may include attempts at Hezbollah-style terror attacks or assassinations in collaboration with criminal enterprises. Prolonged periods of quiet, past or future, should not be mistaken for lost interest in a radical agenda.

Following a Saudi-Houthi agreement, Sana’a will enjoy an influx of funds and less oversight over their ports and travel. This will likely present a golden opportunity for the group to expand its smuggling, training, and overall relationship with the Islamic Republic. Unless the seemingly unlikely scenario emerges in which the Houthis are “rented” by the Saudis, then they seem well-positioned to become more dangerous and more deeply entwined in Iran’s Axis of Resistance.

About the Author

Ari Heistein served as chief of staff and a research fellow at Israel’s Institute for National Security Studies (INSS). Following that, he worked in business development for a cyber intelligence company. Today, he works to bring innovative Israeli startups into the US federal market.

Endnotes

1 Michael Horton, “Hot Issue – War Without End in Yemen: The Saudi-UAE Rivalry to Prolong the Conflict,” The Jamestown Foundation, March 29, 2019, https://jamestown.org/program/hot-issue-war-without-end-in-yemen-the-saudi-uae-rivalry-to-prolong-the-conflict/.

2 Aziz El Yaakoubi, “Yemen's Houthis say Red Sea attacks do not threaten peace with Riyadh,” Reuters, January 11, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/yemens-houthis-say-un-resolution-navigation-red-sea-is-political-game-2024-01-11/.

3 “Arab coalition announces two-week ceasefire in Yemen,” Arab News, April 9, 2020, https://www.arabnews.com/node/1655566/saudi-arabia.

4 “Terrorist Designation of Ansarallah in Yemen,” U.S. Department of State, January 10, 2021, https://2017-2021.state.gov/terrorist-designation-of-ansarallah-in-yemen/.

5 Nick Schifrin and Ali Rogin, “In foreign policy shift, Biden lifts terrorist designation for Houthis in Yemen,” PBS News Hour, February 18, 2021, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/in-foreign-policy-shift-biden-lifts-terrorist-designation-for-houthis-in-yemen.

6 Nabil Hetari, “The Battle of Marib: the Challenge of Ending a Stalemate War,” The Washington Institute, July 9, 2021, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/battle-marib-challenge-ending-stalemate-war.

7 Office of the Presidency of the Yemeni Republic (@Presidency_Ye), X, April 9, 2023, https://twitter.com/Presidency_Ye/status/1645121169773715459.

8 Murdab Abdo (@MuradAbdo22), X, June 23, 2023, https://twitter.com/MuradAbdo22/status/1672222570584702979.

9 Ari Heistein and Elisha Stoin, “Out of Sight, Out of Mind? Understanding the Houthi Threat to Israel,” INSS, April 27, 2021, https://www.inss.org.il/publication/the-houthi-threat-to-israel/.

10 Mohammed Hatem, “Yemen Houthis Claim to Have List of Viable Israeli Targets,” Bloomberg, December 8, 2019, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-12-08/yemen-houthis-claim-to-have-list-of-viable-israeli-targets.

11 Emanuel Fabian, “In first, IDF confirms Houthi cruise missile hit open area near Eilat on Monday,” Times of Israel, March 19, 2024, https://www.timesofisrael.com/in-first-idf-confirms-houthi-cruise-missile-hit-open-area-near-eilat-on-monday/.

12 Agnes Helou, “Purported Houthi strike on Chinese vessel in Red Sea likely a ‘mistake’: Experts,” Breaking Defense, March 25, 2024, https://breakingdefense.com/2024/03/purported-houthi-strike-on-chinese-vessel-in-red-sea-likely-a-mistake-experts/.

13 “What are the impacts of the Red Sea shipping crisis?,” J.P. Morgan, February 8, 2024, https://www.jpmorgan.com/insights/global-research/supply-chain/red-sea-….

14 “The Red Sea Crisis Continues with No Resolution in Sight,” The Soufan Center, February 26, 2024, https://thesoufancenter.org/intelbrief-2024-february-26/.

15 Parisa Hafezi and Andrew Hayley, “Exclusive: China presses Iran to rein in Houthi attacks in Red Sea, sources say,” Reuters, January 26, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/china-presses-iran-rein-houth….

16 South24 | English (@South24E), X, May 20, 2023, https://x.com/South24E/status/1659941441030836224?s=20.

17 “Cairo: The Yemeni Foreign Minister says that he was informed of the handover of his country’s embassy in Damascus,” Yemen Future, October 11, 2023, https://yemenfuture.net/news/17255.