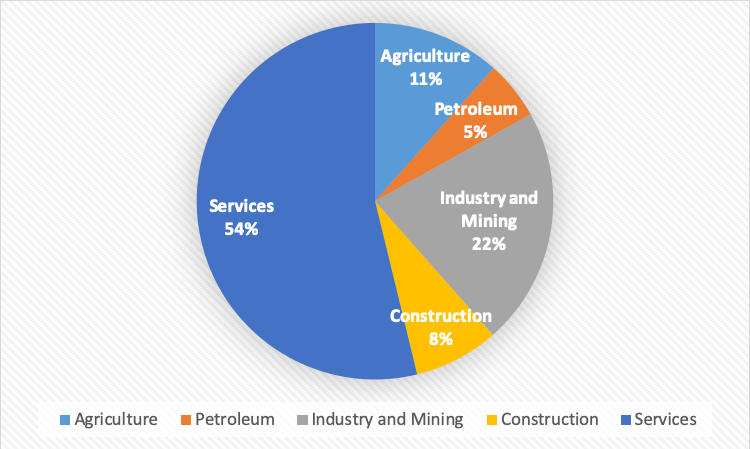

After three years of decline and instability, the Iranian economy has stabilized. Some of the macroeconomic indicators (see table), especially inflation, remain worrying, but the country’s GDP has returned to marginal growth, which is a reminder that the economy has been resilient in the face of massive external and internal pressures. Experts agree that the diversity of economic activity (see graph) has been the key reason for this resilience.

Composition of the GDP for the year ending March 20, 2021

While sanctions, mismanagement, and the coronavirus pandemic have all contributed to the negative economic performance of the past few years, there is no doubt that a potential lifting of sanctions would be a desirable path toward economic recovery. In this piece, we will discuss the medium-term outlook in three distinct scenarios: 1) A return to the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA); 2) An interim deal that would ease the sanctions pressure; and 3) A continuation of the current sanctions regime.

Current trends

The below table summarizes some of the key indicators as of August 2021. The most worrying current trend is high inflation, which will not be contained as long as the current structural deficiencies, such as the high budget deficit and uncontained growth of money supply, are not properly addressed.

Latest macroeconomic indicators

|

Indicator |

Value |

Comment |

|

GDP Growth |

2.1% |

Projected for the year ending |

|

Projected Inflation |

39% |

|

|

Actual Inflation |

45.2% |

12 months ending |

|

Unemployment |

8.8% |

As of end of June 2021 |

Source: Iran Investment Monthly

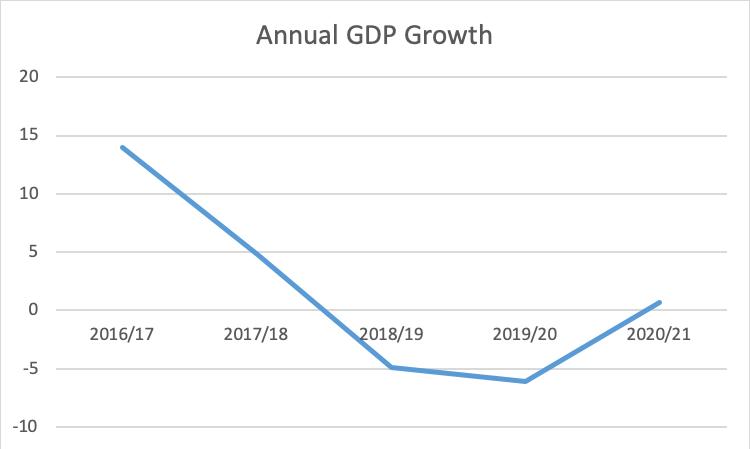

Despite all the shortcomings, indications are that the economy is returning to a period of growth after two years of sharp decline (see graph below). The low growth that was achieved in 2020/21 has been derived from the expansion of the petroleum sector, through increased export of petroleum products.

Annual GDP growth (years ending on March 20)

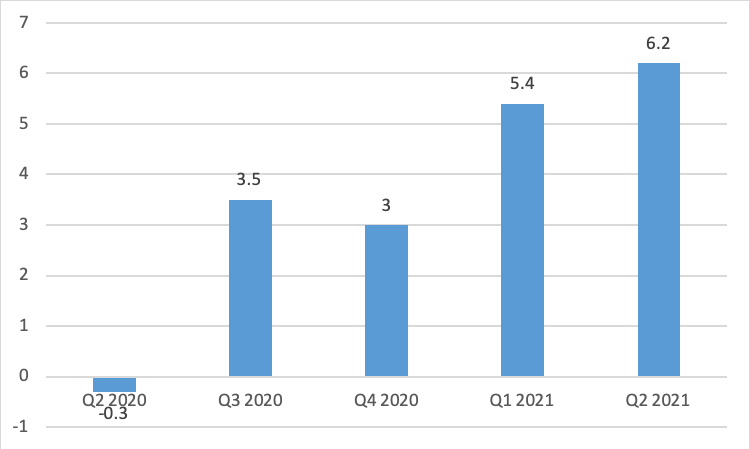

However, the picture of gradual growth becomes clearer when one looks at the data on a quarterly basis. In fact, the growth in the second quarter of 2021 (see graph) has been the highest since the economy moved out of decline.

Quarterly annualized GDP growth rates

According to Central Bank of Iran (CBI) statistics, in the 12 months ending June 20, 2021, the petroleum sector grew by 23.3%, services by 7.0%, industry by 6.1%, and mining by 5.7%. In contrast, the agricultural sector declined by 0.9% and construction experienced a major drop of 12.1%. Interestingly, despite the declines in two of the key providers of jobs, i.e. agriculture and construction, the economy managed to generate 500,000 new jobs, pushing down unemployment from 9.5% in 2020 to 8.8% in mid-2021.

At the end of the second quarter of 2021, Iran’s 12-month exports of goods and services had grown by 35.6%, while imports had increased by 30.5% compared to the previous one-year period. The main negative indicator of the 12 months ending in June 2021 was a negative capital formation of -3.5%. This means that the economy has not been able to invest adequately, which will drive future decline in overall economic performance. Lack of capital investments is partly caused by the government’s financial situation, as planned infrastructure investments have not been realized.

Furthermore, Iran has been suffering as a result of capital flight eating into the economy’s substance. In fact, in the past eight years, there were only two years where the economy experienced a positive capital account (see table).

Capital flight

|

Year |

Capital account |

|

2013/14 |

-9,321 |

|

2014/15 |

+559 |

|

2015/16 |

+2,346 |

|

2016/17 |

-18,288 |

|

2017/18 |

-19,321 |

|

2018/19 |

-16,044 |

|

2019/20 |

-6,669 |

|

2020/21 (nine months) |

-5,159 |

Source: Central Bank of Iran

These overall economic developments point toward medium-level growth in the current Iranian year (ending on March 20, 2022). However, with high inflation eating into the purchasing power of the average Iranian family and the continuing capital flight, the medium-term outlook for the economy could be bleak in the absence of needed political and economic decisions.

Medium-term scenarios

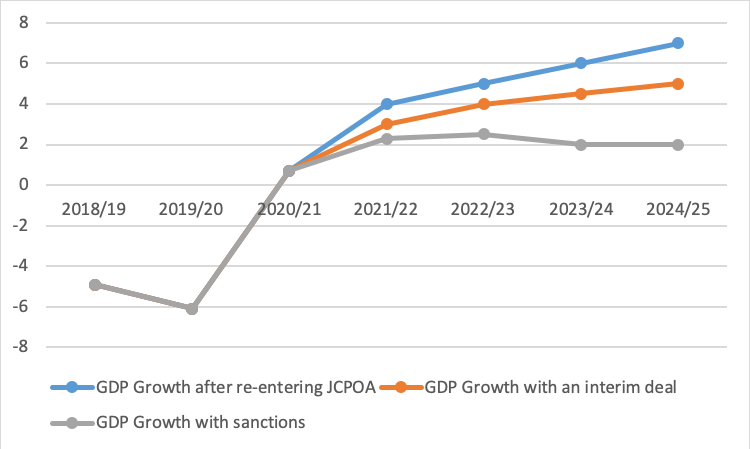

The below graphs depict the outlook of the economy in three distinct scenarios. These are:

Optimistic scenario

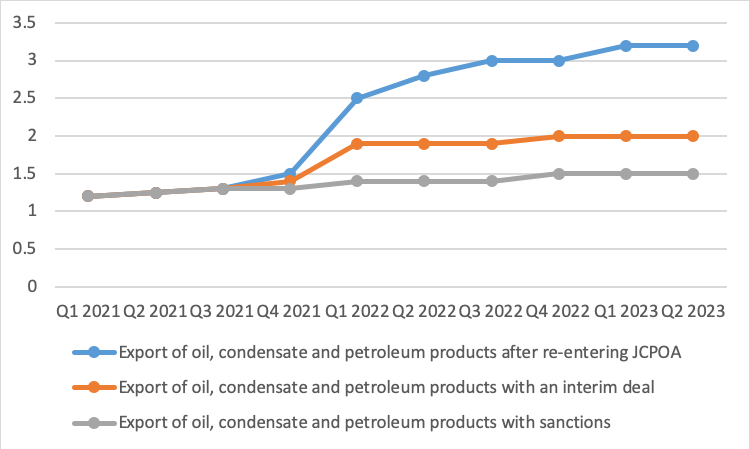

The most efficient path toward economic recovery would be a return to the JCPOA. This would pave the way for Iran to access its hard currency reserves of about $100 billion and facilitate a rehabilitation of Iranian crude oil exports. In fact, a return to the level of crude oil and condensate exports that were achieved in 2016 after the nuclear deal’s implementation would boost the government’s hard currency revenues enormously — resources that would be needed to contain the current budget deficit as well as its direct consequence, i.e. high inflation.

However, a potential lifting of sanctions has to be accompanied by wise economic policies in order to allow the economy to develop in a balanced way. Some of the funds will have to be used to address the budget deficit and some to carry out needed infrastructure investments. Another important element will be to address the money supply and reduce the inflationary pressures caused by unrealistically high bank interest rates. Consequently, serious financial sector reforms will be needed to increase the efficiency of the financial sector and reduce inflation.

A return to the JCPOA would also give the country’s government and enterprises access to the international financial system, reducing the demand on the domestic banking sector.

All in all, in a scenario where sanctions are lifted and adequate economic policies are implemented, the Iranian economy could achieve sustainable growth rates of 5-7%. Containing inflation will be more challenging as serious reforms are needed, but inflation could be contained to around 20% with a decreasing trend.

Middle scenario

There is also talk about a possible interim deal that could de-escalate the sanctions pressure. In this scenario, Iran would discontinue higher level uranium enrichment in return for gradual access to its hard currency reserves as well as waivers for the exportation of 500,000 barrels per day of petroleum products.

Such a development would allow the government to fill some of the financial gaps and give economic players more breathing room. As the access to foreign assets and petroleum exports would be sub-optimal, the government would have to address internal barriers to economic growth, most importantly mismanagement, corruption, and lack of efficiency. Improved governance and greater energy efficiency could also generate some needed economic growth.

Pessimistic scenario

A continuation of the status quo would sustain the external pressure and compel the Iranian economy to find new ways of neutralizing the negative impact of sanctions. So far, the focus has been on import substitution through building domestic capacity, including expansion of refining and petrochemical capacities, a reduction of reliance on Western sources of technology with a special focus on trading with China and Russia, and promotion of trade with Iran’s immediate neighbors.

As seen above, the policies mentioned have stabilized the economy, but this path cannot be sustained easily, as alternative financial resources (such as the sale of government holdings) will diminish over time. A potential subsidy reform or a path toward attracting investments from the Iranian diaspora — both solutions that are being debated — would require a political will that is missing at present.

Furthermore, a key bottleneck will have to be addressed through workable solutions for international transactions to facilitate trade. This could happen through cryptocurrency transactions or via closer collaboration with banking systems of key trading partners, i.e. China, Turkey, Iraq, and Russia. This in turn will require the implementation of the legislation related to the Financial Action Task Force (FATF).

GDP growth in different scenarios

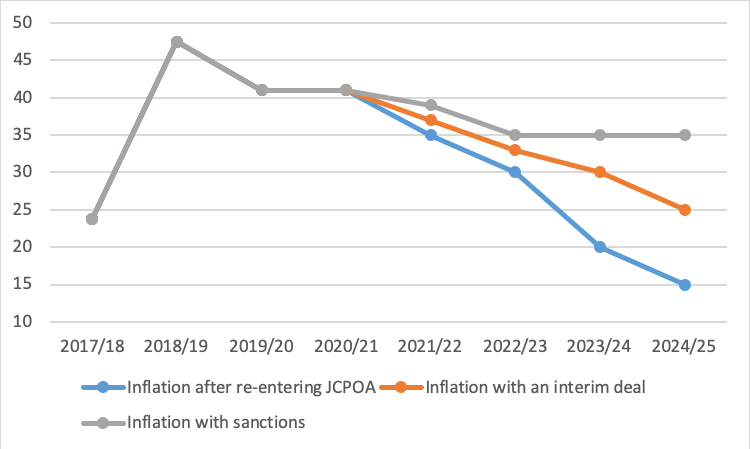

Inflation outlook in different scenarios

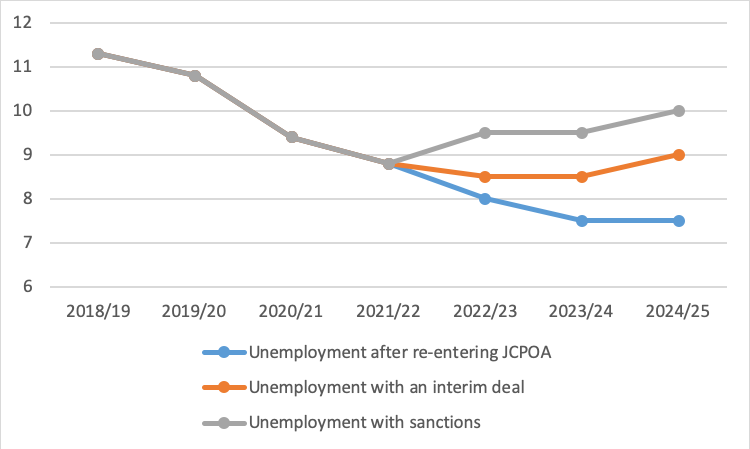

Unemployment outlook in different scenarios

Petroleum exports outlook in different scenarios

Conclusions

Despite all its structural deficiencies, the Iranian economy has survived a challenging period and is set to continue growing. The expansion of domestic industrial and economic capacity as well as the growth of domestic and regional markets will continue to drive the economy forward. The outlook will depend on the outcome of the current negotiations over the future of the JCPOA.

The choices facing the political establishment are clear: Do they wish to pursue a path of reasonable growth and proper economic and technological development or continue the route of fragile economic survival? Something will have to be sacrificed in each scenario, but the potential cost of the pessimistic scenario could be very high. In fact, a continuation of high inflation, capital flight, and the erosion of people’s purchasing power, coupled with the mismanagement of resources and deterioration of the country’s infrastructure, has the potential to drive citizens to the streets to protest, as was the case in July 2021, further undermining the regime’s already faltering legitimacy.

Bjian Khajehpour is the managing partner of Eurasian Nexus Partners and a columnist with Amwaj.media. The opinions expressed in this piece are his own.

Photo by Morteza Nikoubazl/NurPhoto via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.