The Syrian state’s persecution of the population has been well documented throughout the country's more than 11-year conflict through a voluminous stream of victims’ testimonies. Less well understood is the logic behind the violence — who the regime targets and why they inflict such harm. Why do violence and persecution continue against some groups, even after a reduction in immediate conflict hostilities or when they now live as refugees outside of the country?

While individual victims experience random and arbitrary violence (mass detention, shelling, siege, and displacement), the collective experience of the wider group (family, kinship group, neighborhood, town, civil or political organization, etc) speaks to targeted violence, perpetrated in multiple forms by the regime. The violence and persecution against these groups is consistent over time and continues to this day.

The most conflict-affected groups have significant correlations between multiple conflict harms. High numbers of detentions in a family correlate to high numbers of casualties, missing, wanted, and displaced. The targeting then ripples out to those around them. For many of the most affected, their collective experience stretches back over an extended period that predates 2011 — in many cases spanning generations — and has continued past the peak of the conflict violence until today, even when many of these families and communities were forced into exile. As a result, communities and families are now irreversibly splintered by loss, exile, and polarization.

Through detailed analysis of four communities in Syria — Zabadani, Douma, Mlieha, and Deir as-Afir — it has been possible to establish a nascent architecture for understanding the violence and lived experience of each studied area. These areas provide a snapshot that illuminates clear patterns that are likely repeated across the country. Drawing on over a dozen data sets comprising tens of thousands of datapoints, dozens of representative qualitative interviews with affected families as well as key informants, and experiences and data from community groups, civil society organizations (CSOs), documentation organizations, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) relating to these four communities, it has been possible to understand how conflict and security state actions have impacted them, but also how the continuation of persecution into the post-hostility period has changed communities and individuals’ intentions to return in the future.

High correlation between conflict harms

The studied areas are representative of a category of highly affected communities, where a relatively large segment of the population joined the protest movement in 2011, they saw incidents of mass violence and were besieged during the conflict with varying degrees of intensity, until the point of so-called reconciliation (when those who stayed behind agreed to a rigid security screening, and those who disagreed were forcibly displaced).

In each of the studied geographical areas, the correlation of harms to the most affected families, and the variation in levels of harm between families, diverge from a model that would be expected in the case of indiscriminate, collateral damage to co-located groups. Instead, the data, both quantitative and qualitative, describes a pattern of targeting over a long period of time — in many cases decades — before the current conflict. This violence manifests in a multitude of ways: detentions, massacres, displacement, asset freezes, and housing, land, and property (HLP) grievances. Moreover, it shows a pattern of spreading from a core group to their first and second tier of social groups, on lines of kinship, township, and civil or political organization.

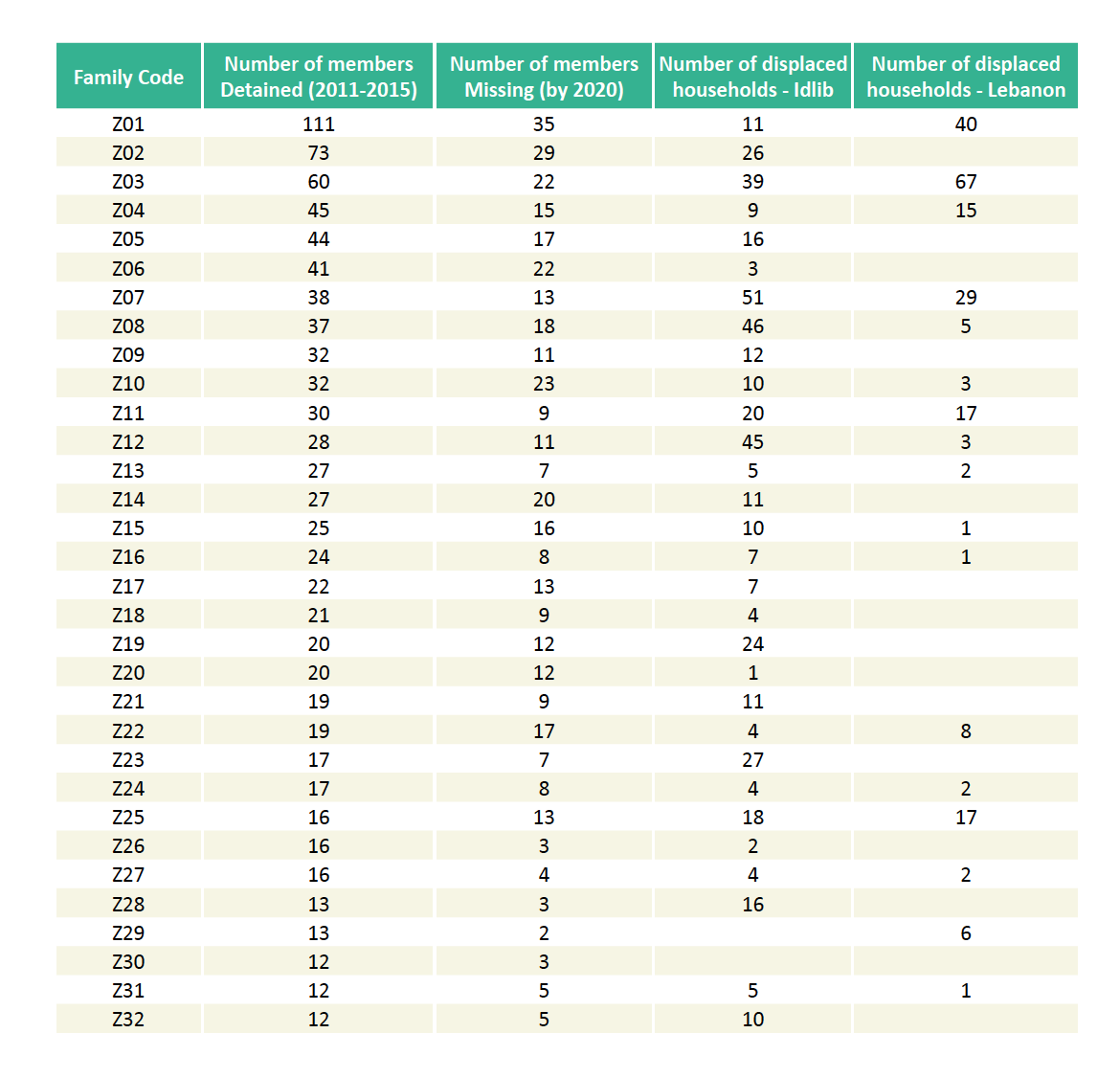

In Zabadani, the families with the highest levels of detention by 2015 were also the families with the largest numbers of displaced households in Lebanon and Idlib, according to a non-exhaustive dataset of displaced families in those areas (see table below). Conflict casualties, too, correlate strongly with these two outcomes.

Table 1 - Zabadani: Numbers detained, missing & displaced

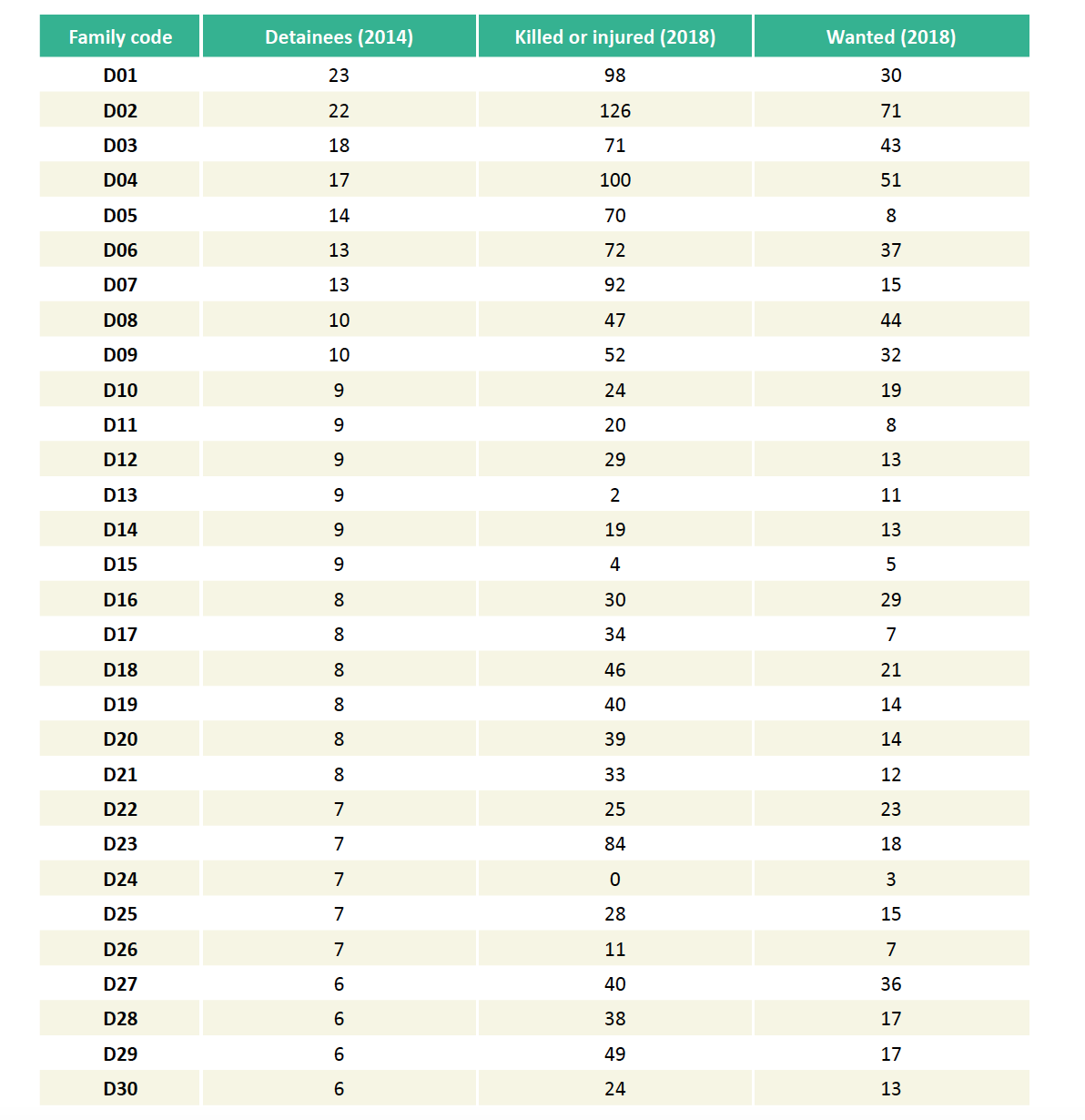

In Douma, these patterns also held true — despite the available data sources differing from those in Zabadani — with detainees, conflict casualties, and names on leaked wanted lists all correlating heavily within the most affected families in the area (see table below). The patterns are the same in the datasets studied in the southern sectors of Eastern Ghouta as well.

Table 2 - Douma: Numbers detained, missing & displaced

In each case, the levels of conflict-affectedness vary significantly between families, but even at the 20, 30, or 50th most affected family level, multiple conflict harms have been wrought on these same groups.

In qualitative interviewing of a representative group of the most affected families in each area, the logic and impact of these experiences came to light. For most, their response to the conflict violence was displacement, often fleeing multiple times. This began with seeking temporary shelter in less conflict-affected areas of their wider neighborhood to avoid violent crackdowns on protests or indiscriminate shelling. A tipping point in the targeting came with mass atrocity violence, both at the local and national levels, and for many it was massacres, or arbitrary arrests of loved ones that became forced disappearances, that eventually drove them further and further from home until they reached the northwest, neighboring states, or Europe.

While the violence is highly targeted, the number of highly targeted families and communities is huge. In each studied area, tens of families, spanning many branches and generations, were highly affected. Together, they represent large percentages of the population. Within these most affected groups, the violence and persecution continued even after they fled. Indeed, the level of targeting suggests an attempt to annihilate certain families, if not through death, then through detention or permanent exile.

Characteristics of affected groups

In many of the most conflict-affected families, grievances with the regime predate the conflict, with families’ early peaceful opposition activities sometimes the result of decades of persecution. For others, who had no pre-war issues with the regime and did not immediately join the revolution, it was the regime's own mass-casualty violence that ensnared their families and communities in subsequent targeted violence and persecution. In all cases, violence adapted to the circumstances.

The pervasiveness of pre-war persecution of some of the most conflict-affected families came through strongly in qualitative interviews. Arrests and harassment of family members in the 1970s, 1980s, and 2000s was a common theme, for both well-known reasons, such as the regime's crackdowns on various political groups and human rights defenders, and lesser-known hyper-local reasons, such as participation in small protests against impunity and corruption among local security actors. These grievances naturally led to participation in the early protests, which in turn raised the security sector's ire and put these families in its crosshairs from the start of the uprising. Violence then spread to their direct community and civil and political networks, suggesting an extreme policy of collective punishment that is similar to disciplinary tactics used by other police states to subjugate their populations.

This broad-brush approach to groups and communities began to condemn more families as the conflict's violence became entrenched. In Zabadani, early detentions in 2011 were generally short but violent. After fighting broke out in the town, alongside the uprising's broader pivot to conflict, a 2013 ceasefire saw civilians attempting to return to their homes arrested en masse at checkpoints, at which time the detained were disappeared. In June 2012, one family in Douma that had not previously experienced arbitrary detentions and did not sense any targeting by the regime lost 21 members in a massacre carried out by regime forces and militias. From that night on, the family was unable to cross checkpoints and more than a dozen of its members were forcibly disappeared, with 15 appearing on leaked wanted lists in 2018. In other areas, such as the southern sector, the regime's pivot from targeting individuals and families with pre-war grievances to mass and indiscriminate violence and detention that then drew groups into the regime's vengeful persecution ultimately drove many who had previously laid low during the early uprising to protest, fight, or flee.

In all cases, the violence adapted to the circumstances. Massacres and detentions peaked before frontlines solidified, at which point siege and indiscriminate conflict violence became the primary modes of regime violence. Both phases caused displacement, often multiple displacements, until these highly conflict-affected communities were eventually displaced to the northwest or outside the country altogether. Where wanted list data is available, it suggests that further violence awaits those within, or associated with, these groups if they were to return to Syria.

Post-hostility violence and persecution

The most affected groups continued to be targeted during the so-called reconciliation process itself. This happened first through forced displacements, wherein tens of thousands of those described in this research boarded buses to the northwest. In Eastern Ghouta, many of those who remained were processed through shelters for internally displaced persons (IDPs), where as many as 1,500 people were arrested by security branches and 1,200 arbitrarily detained and transferred to Adra Central Prison between March 2018 and February 2019. Some 500 of these people were still unaccounted for months after their arrest. In one area of Eastern Ghouta's southern sector, from a group of 600 households that remained behind, 156 arrests were reported. The arrests began in the collective shelters, but have continued up until the present. Of those arrested, 45% remain missing, their fates unknown. In 2018, 278 arrests were recorded by the Syrian Network for Human Rights in Douma, and 189 arrests in the southern sector. Moreover, when the targeting had the effect of almost totally displacing the remaining family members during reconciliation processes, data on post-reconciliation detentions showed whole new groupings of families were targeted.

While the available information highlights a continuation of the violence, the limits of monitoring the security of targeted communities within regime-controlled areas mean that it likely significantly underestimates the ongoing concerns.

Post-hostility information suggests that the most conflict-affected families either never wished to return or have faced multiple additional harms while displaced or during early-return experiences, and in some cases these have changed their long-term intentions. In Ghouta, few expressed any intention to return to Syria and most did not have distant relatives returning at this time. In Zabadani, small numbers of early “organized” returns from Lebanon have highlighted the challenges the targeted groups face.

In addition to detention, conflict violence, and displacement, a range of bureaucratic and legal processes are used to continue the targeting of these affected groups. HLP issues, denial of aid and services, civil litigation, demolition of property, asset seizures, and laws and bureaucratic measures are among the range of tools deployed by the regime and its supporters to continue to persecute and disenfranchise the most conflict-affected. While some affected families that had seen early returns reported detentions, others said that they had been unable to maintain employment or switch electricity and internet on in their homes as the municipality or community sought to “punish” them for the perceived actions of their relatives. Others could not access humanitarian programming, subsidized goods, or other basic needs because of their legal status. The use of civil lawsuits was also reported, with malicious claims used to imprison and disenfranchise these same families and communities.

Across all areas, people reported that regime actors required individuals remaining in Syria to disown relatives in the northwest deemed to be “terrorists” to prove they should not be punished for their relatives’ perceived transgressions. Even these drastic actions did not result in property and assets seized or frozen by the regime being returned to the remaining family. Many of those affected reported that their property and assets were inaccessible to them both inside and outside the country, due to seizures or freezes. This leaves affected communities without their personal or family resources and vulnerable to exploitation. A broader range of HLP issues were reported by the affected communities, ranging from destruction to occupation and expropriation.

Lists of people wanted by the Syrian security services from some of the affected areas leaked online in 2018 and indicate a continuation of the same patterns of targeting. In addition, wanted lists highlighted new targets that had not appeared in detentions data earlier in the conflict, but had come into the regime's view during the besiegement period. Moreover, it was possible to discern which agencies had referred individuals to wanted lists; while the primary referring entities were security branches, in areas where agricultural and light industry sectors, and land use issues around these sectors, formed conflict drivers, line ministries such as the Ministry of Local Administration and the Environment and the Ministry of Industry referred the third-largest numbers of individuals onto wanted lists. This suggests that HLP and economic persecution and the authorities that carry it out are not simply a bureaucratic or conceptual extension of the security sector's framework for persecution of targeted groups, but instead active participants in the security apparatus.

In some cases, post-hostility targeting is altering intentions. In one example, a female-headed household in Lebanon that had lost the male head of household to detention in 2013 had also lost multiple brothers and brothers-in-law to detention and death by torture during the conflict. In 2021, her brother returned and was detained, at which time she chose to send her nearly-of-age son to Europe via Belarus to avoid losing another generation of men to the regime's violence in the event he was picked up and deported from Lebanon. Her son became trapped in Belarus, however, before being sent to a camp in Russia. For such families, decisions about returning to Syria are not about the parameters or veracity of a “reconciliation” agreement, but rather visceral fear born of decades of lived experience spanning generations and multiple family branches that have been harmed or killed by the regime.

Concerns for the future

The report findings provide significant reason to believe that for these highly conflict-affected families and communities, discussions around return to Syria, or eventual political transition or settlement, must take into account the likelihood of future mass atrocity violence against them.

While the research focused on four communities, similarities in the level of targeting and repeated patterns and reported base data on detentions, massacres, and displacement across all areas suggest that while further research is required, it is likely that this pattern would hold for villages, towns, cities, and neighborhoods with similar conflict experiences across Syria, including Homs, al-Tadamon, Qusayr, Darayya, Qaboun, Khan Sheikhoun, and so on. Moreover, communities of concern for the regime without a shared geographical footprint, such as those sharing political beliefs or professions deemed to be of threat, would likely see a similar pattern too. Extrapolated out, the targeted groups form tens of thousands of missing and disappeared and millions of displaced. Many find themselves in these circumstances because of collective punishment against communities, or even because of their proximity to the regime's own mass atrocity violence.

For many policymakers and diplomats, Syria’s now-frozen conflict — and the mass displacement crisis surrounding it — is seen as comparable to an environment like pre-2021 Afghanistan. Instead, this research suggests that the long-term picture for returns to Syria has more in common with Myanmar, where a premature return of Rohingya refugees and IDPs to Rahkine Province resulted in enduring rights abuses that gave way to further mass atrocity violence, genocide, and displacement.

This research does not just hold lessons for the refugee and IDP returns picture, but raises questions about the increasingly widely accepted framing of the violence as authoritarian over-reach combined with a now-reduced violent conflict. With many now accepting that Bashar al-Assad will remain in power, calculations are being made about the level and breadth of political and behavioral reforms that might be deemed acceptable or feasible. This research suggests that while any reforms would still be welcome, if achievable, at a small scale they will have little meaningful impact on the ability to reintegrate Syria's three territories into a single state, or to allow Syrians to safely return to their home country.

This article is drawn from detailed research originally produced as part of the European Institute of Peace's Syria policy program, with support from the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Original research authored by Fadi Adleh, Emma Beals, Tom Rollins, and Nada Ismael, with contributions from a wide range of civil society organizations, documentation organizations, researchers, NGOs, community networks, and individuals, whose safety is paramount, but whose involvement has been critical to these efforts.

Photo by LOUAI BESHARA/AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.