Summary

A question as to the value of a U.S.-Egypt Free Trade Agreement (FTA) misses the point. The question should not be whether an FTA would be in the interest of both parties since there is abundant evidence that it would. The question is what kind of FTA would best suit the needs, both short and long term, of the two parties: shallow integration or deep integration? This report argues that notwithstanding several hurdles, it is in the interest of both countries to move swiftly and decisively toward a deep FTA.

Contents

- Executive summary

- Introduction

- The lay of the land

- There is nothing free about a free trade agreement

- For the US, it's worth the trouble: Egypt as a potential partner

- The impact of an FTA on Egyptian domestic reform

- There are compelling reasons to move ahead

- Options vs. opportunity costs

- The road to an FTA is littered with potholes

- Now what? Recommendations and next steps

- Endnotes

Executive summary

A question as to the value of a U.S.-Egypt Free Trade Agreement (FTA) misses the point. The question should not be whether an FTA would be in the interest of both parties since there is abundant evidence that it would.

The question is what kind of FTA would best suit the needs, both short and long term, of the two parties: shallow integration or deep integration? The former, which would typically tackle surface trade matters like qualitative restrictions, standards, and border issues, is easier to achieve, but would be of limited long-term value to both countries. The second, deep integration, holds the promise of reaching beyond enforcing standards to real reform in areas like investment, labor rights, environmental impact, judicial reform, and intellectual property rights, all of which are mainstays in the U.S. negotiating position and imperative to Egypt’s long-term development.

A mutually beneficial agreement

This report argues that notwithstanding several hurdles, it is in the interest of both countries to move swiftly and decisively toward a deep FTA. An agreement would provide significant economic benefits to U.S. businesses and boost economic reform in Egypt by attracting foreign direct investment (FDI), improving efficiency, enhancing domestic reform implementation, and generating much-needed new jobs. The advantages are myriad, for both the United States and Egypt; and while trade and profit are certainly important, they are only part of the wider potential benefits for the two countries.

FTAs are inherently political tools as much as they are economic tools. On the economic side, an Egypt FTA should not be a particularly difficult sell: Spanning two continents and carrying approximately 10 percent of world trade through the Suez Canal, the country is already home to 35.4 percent of U.S. direct investment in Africa and almost 46.2 percent of U.S. direct investment in the Middle East. The two countries currently have a vibrant trade relationship — almost $7.5 billion went both ways in 2018 — of which the United States racked up a surplus of nearly $2.6 billion.1

A natural investment

Egypt continues to look increasingly attractive to investors. New natural gas discoveries (including the Zohr field, the largest in the Mediterranean) seem poised to turn the country into a regional energy hub. A report from the UN recently named Cairo as the most attractive city for investors in Africa, just beating out Johannesburg.2 Crucially, the criterion was the city’s ability to serve as a gateway to Africa — a market of some 1.2 billion people.

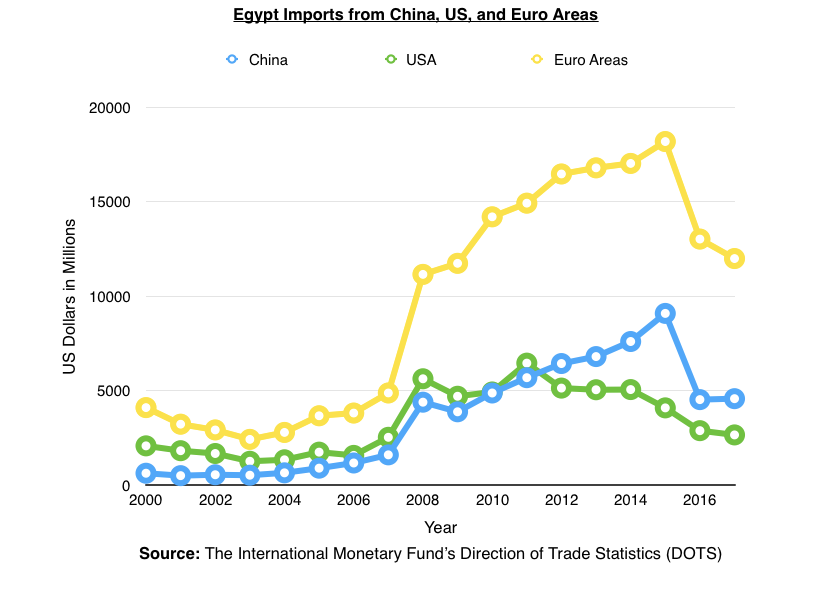

There are also opportunity costs for the U.S. of not pursuing an FTA. Since it was signed in 2004, the EU-Egypt Association Agreement has more than doubled trade between Egypt and the EU. It’s been such a success that an additional agreement on agricultural products, processed agricultural products, and fisheries was signed in 2010.

This success has come at a double potential cost for U.S. exporters. Meredith Broadbent, a U.S. International Trade Commissioner, formerly with the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), put it succinctly: “The new reciprocal concessions, which Egypt began to implement in 2007, give a competitive advantage to Egyptian exports competing with similar products from the U.S.”3 Or, as one U.S. negotiator put it, “Until we do [conclude an FTA], Europe will continue to eat our lunch.”4

This situation will only be exacerbated by Brexit, currently set for Oct. 31st, 2019, so time is very much a factor in these discussions.

Geopolitical aspect

There is also a pressing geopolitical facet to engaging with Egypt. Russia appears to understand the importance of integrating itself back into the region and, as is clear from its involvement in Syria, President Vladimir Putin is happy to play the long game. Egypt offers several important geopolitical advantages, among them the Suez Canal and the country’s potential influence on oil-rich Libya.

Russia is only one suitor; China is busy opening new markets as well. Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi and Chinese President Xi Jinping signed five cooperation agreements in Beijing at the beginning of September 2018.5

Reform efforts reinvigorated

Both the U.S. State and Commerce departments have emphasized that Egypt has work to do on meeting fundamental International Labor Organization (ILO) standards and environmental agreements. The Department of State goes further, citing the need for “vigorous enforcement of labor standards including freedom of assembly, prevention of child labor and trafficking, and customs and trade facilitation, adoption of U.S. rather than U.N. auto standards and, of course, enforcement of intellectual property rights provisions.”

These reforms would only come about through a deep integration FTA, which would actively engage institutional reform in areas like environmental law, customs, labor rights, the judiciary, and transparency.6

Potential despite difficulties

The fact that discussions for an FTA have dragged on makes those discussions more arduous, but no less important. The U.S. stands to gain significant positive economic benefits. While they may not be enormous in relative terms, due to the overall size of its economy, they represent very real gains for the U.S. businesses involved. More importantly, there is a serious opportunity cost in letting other countries step up and take the U.S.’ share of the economic pie. Just as importantly, perhaps, a deep FTA would likely provide the U.S. with a clear path to the reforms it has consistently demanded that Egypt undertake — in a positive, proactive manner.

A quick look at Egypt’s modern history will show that generally, economic reform has ushered in social reform, whether it was the period following the late President Anwar Sadat’s Open Door policies in the mid-1970s, which dragged Egypt away from socialism, or the period following the Economic Restructuring and Structural Adjustment Program (ERSAP), with its rise in media freedoms, student engagement, and labor union activity in the late 1990s.

As for Egypt, the economic benefits are more obvious, but the promise of market– backed reform, via a deep FTA that includes services and investment, will be even more desirable. Successful economic reform is likely to lead to economic prosperity and greater employment opportunities — a vital requirement for a country where poverty and lack of jobs have been linked to radicalization and terrorist recruitment. Ultimately, a stable Egypt is in the U.S.’ geopolitical interest.

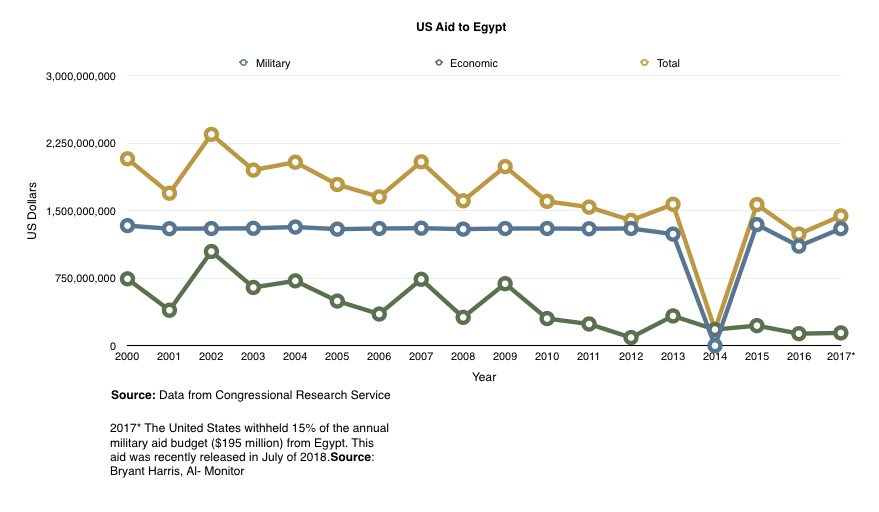

There have also been indications on the diplomatic front that both the current U.S. administration and the Egyptian government are interested in a closer relationship. The release of $195 million in previously frozen military aid to Egypt in July 2018 and U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s visit to Cairo in January 2019 may be tentative signs that the political will needed to provide more fertile ground for economic discussions is present.

The road ahead

The political and economic conditions for an FTA are more auspicious now than they have been in decades, between a trade-focused U.S. administration that appears willing to move toward warmer relations and an investment-focused Egyptian leadership that has thrown all its weight behind attracting and retaining FDI.

A deep FTA presents clear and desirable advantages to both sides, and it is important to move forward and grasp the opportunity.

"Notwithstanding several hurdles, it is in the interest of both countries to move swiftly and decisively toward a deep free trade agreement.”

Introduction

A U.S.-Egypt Free Trade Agreement (FTA) has been discussed across board tables, with varying degrees of liveliness, for almost two decades.

To be clear though, the question that needs to be asked is not whether an FTA would be in the interests of both parties, but what kind of FTA would best suit their needs, both short term and long term. The options are either shallow integration or deep integration.

The former, which would typically tackle surface trade matters like qualitative restrictions, standards, and border issues, is easier to achieve; however, it can have negative side effects like trade diversion and is of limited long-term value to both countries, for reasons that will be expanded upon in this paper.

The second option, deep integration, holds the promise of reaching beyond enforcing standards to real reform in areas like investment, labor rights, environmental impact, judicial reform, and intellectual property rights (IPRs), all of which are mainstays in the U.S. negotiating position and imperative to Egypt’s long-term development.

This report argues that notwithstanding several hurdles, it is in the interests of both countries to move swiftly and decisively toward a deep FTA. The advantages are myriad, for both the United States and Egypt; and while trade and profit are certainly important, they are only part of the wider potential benefits for the two countries.

This paper will not undertake an impact assessment since that would be beyond its technical scope, but it will deal with indicators illustrating the mutual benefits for both countries. It will lay out an assessment of the status quo, followed by a brief background on the discussions and negotiations on this FTA to date. Beginning with an exploration of the compelling reasons to move forward with a deep FTA, it will then examine the impediments to such an agreement, before finally moving on to concrete suggestions and recommendations for how to proceed.

“Since it was signed in 2004, the EU-Egypt Association Agreement has more than doubled trade between Egypt and the EU."

The lay of the land

FTAs are inherently as much political tools as they are economic ones. In the Middle East, the United States currently has FTAs with Bahrain, Israel, Jordan, Morocco, and Oman. In some cases, as with Jordan, the United States’ trade balance in 2017 was a mere $234 million and actually jumped to a deficit of $195 million in 2018. In the case of Israel, the U.S. trade deficit was over $8 billion in 2018.7 FTAs, then, appear to be almost as much about relationships as they are about economics, particularly for the United States, for which the agreements seem to be driven more by political than economic gains.

This is not to say that the economics aren’t a priority; market access is a primary factor in trade negotiations, and the relationship needs to be mutually beneficial. On the economic side, an Egypt FTA should not be a particularly difficult sell: The country is already home to 35.4 percent of U.S. direct investment in Africa and almost 46.2 percent of U.S. direct investment in the Middle East. The two countries currently have a vibrant trade relationship — almost $7.5 billion went both ways in 2018 — of which the United States racked up a surplus of nearly $2.6 billion.8

In the aftermath of two popular uprisings in eight years, Egypt has clambered back up the precipice and toward macroeconomic stability, slashing previously sacrosanct subsidies — at no small domestic political cost — and adopting a flexible exchange rate regime leading to an immediate and considerable devaluation of the Egyptian pound. It’s a testament to the government’s fiscal policies that the pound has held steady and economic observers expect it to continue to do so.9 As of the end of June 2019,10 it was trading at its strongest against the dollar since March 2017.11 Egypt has also very clearly signaled that it is open for business; among other things, it passed a remarkably comprehensive new investment law after intensive consultation with investors, enacted more business reforms in 2018 than it had done in over a decade, and removed foreign currency restrictions and controls.

Egypt and the United States have had a solid, mutually beneficial connection for almost half a century, but recent political developments in Egypt have complicated matters. Since the January 25th Revolution in 2011, consistent misunderstandings, coupled with a troubling domestic human rights situation in Egypt, have led to a growing perception that Egypt and the United States have divergent interests; and that has, among other things, contributed to occasionally frosty waters, and a decrease in U.S. economic and military aid to Egypt. The carrot-and-stick method is not an approach that has ever worked well in Egypt, and it has further compounded the diplomatic strain.

However, other domestic issues aside, the current administration in Egypt is extremely serious about an IMF-driven economic reform program that kicked off in late 2016.12 This program, which has seen a major commitment from the government, is bearing fruit: The latest IMF country report, in April 2019,13 is largely positive with a strong endorsement of the government’s policies and reforms.14 While IMF praise is valuable in its own right, Egypt received another boost in August 2018, when Moody’s Investor Service upgraded the country’s long-term issuer rating from stable to a positive B3.

A bilateral FTA could further boost economic reform by attracting foreign direct investment (FDI), improving efficiency, enhancing domestic reform implementation, and generating badly needed new jobs.

To see the benefits of a deep FTA, one need look no further than Mexico, where deep reforms mandated by the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) resulted in increased FDI and employment.15 It will not be an easy lift by any means; there are a myriad of wrinkles to iron out. However, a concrete set of recommendations for interim measures may help shorten the path while increasing trade on both sides. Considering the requirements of an FTA, the United States, in addition to reaping economic benefits, would also encourage reform to improve labor standards and IPR protections. Perhaps most importantly, by contributing toward a more vibrant and prosperous economy, the United States will help guarantee the domestic stability of a valuable partner in a tumultuous region.

"On the economic side, an Egypt FTA should not be a particularly difficult sell: The country is already home to 35.4 percent of U.S. direct investment in Africa and almost 46.2 percent of U.S. direct investment in the Middle East."

There's nothing free about a free trade agreement

The Middle East Free Trade Area (MEFTA) was the 2003 brainchild of former U.S. President George W. Bush, intended as part “of a comprehensive effort to support the agenda in the Arab world for economic reform, job growth, and development.” At the time, the U.S. had existing FTAs with Israel (1985) and Jordan (2001). Morocco, Bahrain, and Oman were brought on board fairly rapidly as well.

Egypt’s FTA negotiations, however, hit one bump after another. The first was a perception on the U.S. side that economic reforms were slowing down, a factor that Ahmed Galal and Robert Lawrence feel should actually have made an FTA more compelling, in the sense that a deal conditioned on domestic reform might have restored momentum to the process.16 The second reason was what Galal and Lawrence describe as “a loss of trust” between Egypt and the U.S. in the wake of a World Trade Organization (WTO) case brought by the U.S. against the EU in May 2003. Egypt had initially signed on as a co-complainant with the U.S. but later reversed its position, leading some to question its reliability. The fallout was significant — enthusiasm in the U.S. waned and in Egypt, concerns were raised that, considering the change in U.S. attitude, negotiations over an FTA could be used to apply political pressure.

While those hurdles were eventually overcome, the road has been littered with potholes. Both sides have a litany of concerns they feel must be addressed before moving forward. The delay has not been to Egypt’s advantage. Successive FTAs have become increasingly technical, and the U.S. negotiating position has become ever more complex. This has, in effect, meant that the goal posts have continued to move further away for Egypt.

“The two countries currently have a vibrant trade relationship — almost $7.5 billion went both ways in 2018 — of which the US racked up a surplus of nearly $2.6 billion.”

For the US, it's worth the trouble: Egypt as a potential partner

FTA talks have been consistently described by negotiators on both sides as a heavy lift. The question, of course, arises as to whether the agreement is worth the effort, particularly after so many years of difficult negotiations and in a U.S. political climate which, arguably, is not particularly welcoming to trade liberalization.

The answer is that ever since Egypt first started to tug away from the Soviet Union and toward the United States in the 1970s, the Egypt-U.S. relationship has been a mutually beneficial one.

Egypt spans two continents, carries approximately 10 percent of world trade though the Suez Canal, and borders five countries, helping to maintain a delicate regional balance of power. The most populous country in the Middle East, it has approximately 100 million inhabitants, almost one-quarter of whom are aged 18- 29. Egypt’s peace with Israel in 1979 was remarkable, considering that there had never been a war fought against that country in which Egypt had not played a leading role. Almost 40 years later, it has a solid, mutually advantageous relationship with Israel, displaying a pragmatic adaptability.

U.S. diplomacy toward Egypt has included economic and military aid since the late 1970s; while economic aid has seen a significant drop over the past two decades, military aid still stands at almost $1.2 billion annually.17 That aid, and the relationship it has built, has helped ensure that the U.S. military receives expedited passage through the Suez Canal and fly-over rights for a range of regional engagements. The rise of Islamist extremist violence over the past decade has further deepened military and security cooperation between Egypt and the U.S. (and, even more so, between Egypt and Israel).

Since the January 25th, 2011 Revolution, however, the U.S.-Egypt relationship has taken something of a battering. Two uprisings, including the removal of former President Mohammed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood by the military, after mass demonstrations against his rule, led to a worsening security situation and a corresponding rise in human rights abuses. Relations began to cool and many U.S. analysts started to claim that Egypt was no longer a relevant regional player.

There would be little point attempting to argue that space for expression, let alone dissent, in Egypt has not shrunk drastically, nor that its internal issues have not preoccupied its diplomats and leaders since 2011. But any assessment that Egypt is no longer a regional player is wildly inaccurate. There are few, if any, regional discussions in which Egypt is not playing a significant role. It is the fulcrum of any negotiations in the Occupied Territories, or in Libya. After ignoring African relations for over 40 years, the current Egyptian administration has been busy shuttling back and forth across the continent, building economic bridges and reasserting influence, particularly now as Egypt serves as head of the African Union in 2019.

Egypt’s new natural gas discoveries (including the Zohr field, the largest in the Mediterranean) look poised to turn the country into a regional energy hub. To achieve this aim, Egypt is counting on leveraging its unique position on the Suez Canal, its land bridge between Africa and Asia, and its well developed infrastructure, not least its extensive pipeline network and two idle gas liquefaction plants. Earlier this year, the country helped form a new Mediterranean gas forum with Cyprus, Italy, Israel, Jordan, Greece, and Palestine, to create a regional gas market, cut infrastructure costs, and offer competitive prices, according to Egypt’s Petroleum Ministry.

While the material rewards are significant, there are other considerations at play as well. If the United States were to step away from Egypt, it would signal a serious disengagement from the region, leaving a vacuum that others would be delighted to fill. Russia appears to understand full well the importance of integrating itself back into the region and, as is clear from its involvement in Syria, President Vladimir Putin is happy to play the long game. Egypt offers several important geopolitical advantages, among them the Suez Canal and the country’s potential influence on oil-rich Libya.

Russia is only one suitor; China is busy opening new markets as well. Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi and Chinese President Xi Jinping signed five cooperation agreements in Beijing at the beginning of September 2018.18

There has been criticism of Egypt’s relations with Russia and China by various U.S. media and analysts, but ultimately, it is the responsibility of the Egyptian leadership to expand its international influence as much as it is able. Egypt has made it clear that the U.S. is its preferred partner, but it cannot isolate itself waiting for that partner to return the compliment.

There have, however, been indications on the diplomatic front that both the current U.S. administration and the Egyptian government are interested in closing the gap. The release of $195 million in previously frozen military aid to Egypt in July 2018 and U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s visit to Cairo in January 2019 may offer tentative signs of the political will needed to provide more fertile ground for economic discussions.

“An FTA could further boost economic reform by attracting FDI, improving efficiency, enhancing domestic reform implementation, and generating badly needed new jobs.”

The impact of an FTA on Egyptian reform

In 2003, Galal and Lawrence kicked off what would be the first of several studies on the viability of an FTA. One of their key questions related to “the dynamic benefits that result if the agreement stimulates productivity growth and investment, enhances policy credibility, and reinforces domestic economic reforms and institutional development.”19

One stated goal of U.S. foreign policy toward Egypt (and the region in general) has been the desire to bring about “reform.” This term can have fairly elastic connotations, but it is generally understood to encompass economic and social reforms. The last several years have seen differences between Egypt and the U.S. as to the extent of Egypt’s reform, with the U.S. voicing concerns specifically over the state of human rights in the country.

Egypt has responded that it is dealing with an unparalleled security risk the likes of which it has never before faced. The aftermath of two uprisings includes an uptick in extremist violence, an insurgency in the Western Desert, and social strain from austerity measures undertaken as part of major economic reforms to bring the country back to a solid economic footing.

The Egyptian government’s current stated priorities are ensuring both economic stability and domestic security. The resulting strain has led to decreased aid, a reversal by the Obama administration of cash flow financing (a process which allowed Egypt’s military to spread out loan repayment for arms purchases), and an occasionally frosty relationship. This iciness peaked during the infamous NGO foreign funding case with the felony convictions of 43 defendants, including 17 Americans tried in absentia. The country’s highest appeals court overturned the convictions of 16 of the defendants in April 2018,20 and on Dec. 20th, 2018 all 40 defendants who had been sentenced and appealed their convictions were acquitted.

While the U.S.-Egypt relationship appears to be on the mend, the issue of human rights still dominates, with the U.S. politely insisting on reform and Egypt politely insisting that it will not brook international interference in its domestic affairs, regardless of the stakes. It is important to note that the Egyptian government is not operating in a vacuum on this issue; Egyptians have always been prickly about what they perceive as external interference in domestic affairs, and the majority of Egypt’s population is currently focused on the same two issues prioritized by the government: the economy and security.

A quick look at Egypt’s modern history will show that generally, economic reform has ushered in social reform, whether it was the period following the late President Anwar Sadat’s Open Door policies in the mid-1970s, which dragged Egypt away from socialism, or the period following the Economic Restructuring and Structural Adjustment Program (ERSAP), with its rise in media freedoms, student engagement, and labor union activity in the late 1990s.

Again, the requisite reform here would only come about through a deep integration FTA, which would actively engage institutional reform in areas like environmental law, customs, labor rights, the judiciary, and transparency.21

Economic empowerment has a momentum of its own and while an FTA is hardly likely to prove a panacea for all Egypt’s economic ills, it will provide an important indication that the U.S. is invested enough in its relationship with Egypt to help it help itself.

“Egypt’s most urgent issue is its labor force, which is expected to swell to a staggering 80 million by 2023."

There are compelling reasons to move forward

Economically, Egypt is keen on new investment and has jumped through hoops to get it. Foremost among the country’s new investment incentives is Law 72 of 2017, known simply as the new investment law.22 Its stated aim is to “promote foreign investments by offering further incentives, reducing bureaucracy, and simplifying and enhancing processes.” It tackles many of the issues that have made FTA negotiations problematic, including instruments for dispute resolution and IPRs. The government has indicated in no uncertain terms that it is serious about its economic reform program, enacting a series of austerity measures and subsidy cuts — including to previously untouchable goods like fuel, electricity, and water — risking considerable domestic discontent. It appears to be paying off; other domestic issues aside, Egypt’s economy is making a strong recovery. The country has managed to knock its current account deficit down from over 5 percent of GDP to less than 2.5 percent — from sustainable income sources.23 In 2018, growth climbed to 5.5 percent,24 above the 5.2 percent the IMF had projected. The country’s budget deficit was 8.4 percent25 in 2018, down from a five-year low of 9.8 percent the previous year, and was projected at 7 percent for 2019/20 by the Ministry of Finance.26

Analysts note that the fiscal sustainability picture is improving, with a stable currency and gradually falling inflation, in the wake of the subsidy cuts and recovery in foreign currency lending. Foreign reserves are at an 18-year high: As of May 2019 they were at almost $44.3 billion, up from the historic low of $13.4 billion in 2013.27

Egypt’s bond yields are among the highest in emerging markets. The Egyptian pound proved relatively immune to a recent rout that crippled Argentinian and Turkish currencies, transforming the country into a haven for debt investors. The pound’s 30- day historical volatility has fallen to below 2 percent, down from a high of 3.4 percent in June 2018. In contrast, the Turkish lira’s one-month historical volatility topped 70 percent while Argentina’s peso was almost at 20 percent.28

Just as importantly, there appears to be significant commitment by the Egyptian leadership to attracting, and retaining, FDI. In 2015, Mercedes Benz stopped assembling cars in Egypt, citing the lack of foreign currency and the implementation of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). The terms of the EU-Egypt Association Agreement required that Egypt gradually eliminate tariffs and customs duties, essentially ensuring that by 2019, the price of cars manufactured in Europe would be equal to the cost of locally assembled ones, if not cheaper. In January 2019, Mercedes announced that it would start assembling in Egypt again. The reason appears to have been an all-out effort at evolution on the Egyptian government’s part: A previous $700 million dispute between the company and the Egyptian Customs Authority was settled, after much effort from the highest levels of Egyptian government. Of particular note to U.S. auto manufacturers is that one other possible reason for Mercedes’ change of heart are the prohibitively high customs imposed on its SUVs manufactured in the U.S. — a casualty of the U.S.-China tariff wars.

As mentioned earlier, Russia and China have stepped up with a canny mix of investment and soft power. Russian investment in Egypt is expected to reach $8 billion over the next two years,29 and the two countries’ leaders inked an agreement for Egypt’s first nuclear power plant late last year.

Egypt is also attempting to take advantage of its geographic location. A recent report from the U.N. named Cairo as the most attractive city for investors in Africa, just surpassing Johannesburg.30 Crucially, the criterion was the city’s ability to serve as a gateway to Africa.

That introduces two additional factors to take into account when considering the viability of an FTA between the U.S. and Egypt: the possibility of Egypt as an African gateway and the fact that the U.K. is its largest single country investor.

The African market boasts 1.2 billion people. Rand Merchant Bank’s annual report Where to Invest in Africa 2018 listed Egypt as the continent’s most attractive destination, unseating South Africa, which had held the position since the report’s inception. For trade implications, the U.S. need look no further than Mexico. Deep integration reforms ushered in by NAFTA resulted in Mexico becoming an attractive investment destination that presented countries like Japan with an opportunity to export their goods, manufactured in Mexico, to regional markets, including the U.S. Thanks to FTAs Egypt has signed with other African blocs, it can offer a portal to a combined consumer base of 1.2 billion people.

As previously mentioned, Egypt had made the mistake of letting its Africa policy lapse under former President Hosni Mubarak. President el-Sissi shows no sign of making the same mistake; to date, he’s visited Nigeria, Gabon, Tanzania, Rwanda, Chad, Sudan, and Ethiopia. The country is a signatory to the African Continental Free Trade Area Agreement (AfCFTA) and is poised to double its exports to the continent. In December 2018, Egypt hosted the Africa Business Forum for the second year in an effort to increase intraregional trade and boost investment in the continent. Combined with the fact that Egypt took over the chairmanship of the African Union in 2019, the possibility that Egypt will become a gateway for African trade and investment is one that should be seriously considered.

“Auto standards are a point of contention between the U.S. and Egypt, although Egypt has expressed a willingness to resolve this by adopting a dual standard."

Options vs. opportunity costs

Britain is currently Egypt’s top trading partner. In 2017, former Egyptian Minister of Trade Tarek Qabil and the then British Ambassador to Cairo John Casson held talks on the impact of Brexit.

Those talks included the goal of doubling the trade volume between the two countries,31 an entirely natural aim in light of the uncertainty that Brexit has thrown into the proceedings. Britain would, however, have to compete with the current EU-Egypt Association Agreement. Signed in 2004, the agreement has more than doubled trade between Egypt and the EU. It’s been such a success that an additional agreement on agricultural products, processed agricultural products, and fisheries was signed in 2010. The agreement is particularly relevant due to its origins; it replaced a unilateral emerging market trade preference program under which most Egyptian exports received duty-free access to EU markets.

Its success has come at a double potential cost for U.S. exporters. Meredith Broadbent put it succinctly: “The new reciprocal concessions, which Egypt began to implement in 2007, give a competitive advantage to Egyptian exports competing with similar products from the U.S.”32

Another area of possible concern is Article 47 of the EU-Egypt Association Agreement. It obligates the parties to “aim to reduce differences in standardization and conformity assessment.”33 The attempts to juggle standards placed enormous pressure on Egyptian authorities. As one U.S. Department of Commerce official dryly put it, “We frequently find a bias toward ISO, lots of ‘I’s which can lock out U.S. companies.”34

One of the most significant examples of non-tariff barriers are the auto standards referred to earlier in this report. As noted, Egypt has declared a willingness to resolve this by adopting a dual standard, and it remains up to the U.S. negotiators to explore the issue further.

Again, both parties should look beyond shallow integration to a deep FTA. Broadbent notes that in July 2011, the president of the European Commission, Jose Manuel Barroso, travelled to Cairo and delivered a speech that included the following: “In the long term, we should work on a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) that firmly ties Egypt into the world’s largest market — the EU, with its half-billion investors, businesses, and consumers. And we should not lose sight of our long-term vision of a full free trade zone between the European Union and the Southern Mediterranean.” According to Broadbent, the lack of an FTA with Egypt means that the U.S. is missing the accompanying institutional networks of cooperation to work though routine issues of trade and commercial regulation.

This is not to imply that U.S. officials don’t talk to their Egyptian counterparts — far from it. However, particularly in recent years, much of the heavy lifting has been done by private business attempting to push the issue up a steep incline. Both U.S. and Egyptian private companies have voiced concerns about doing business. (Private businesspeople, however, have continued to keep the channels of communication open, particularly through trade organizations and chambers of commerce.)

U.S. agricultural exporters, for example, have questioned the consistency of Egypt’s sanitation criteria; U.S. soybeans rejected by Egypt were then accepted by European importers. This led to Egypt’s paying a higher risk premium — particularly problematic since Egypt is the world’s fourth-largest importer of U.S. soybeans. Egyptian manufacturers, particularly agricultural ones, are keen on an FTA, but wary of U.S. goods flooding the Egyptian market. The relationship is not a particularly equal one, and the size of the U.S. market is a factor Egypt needs to take into account without lapsing into protectionism.

“The U.S. State and Commerce departments have emphasized that Egypt has work to do on fundamental International Labor Organization standards."

The road to an FTA is littered with potholes

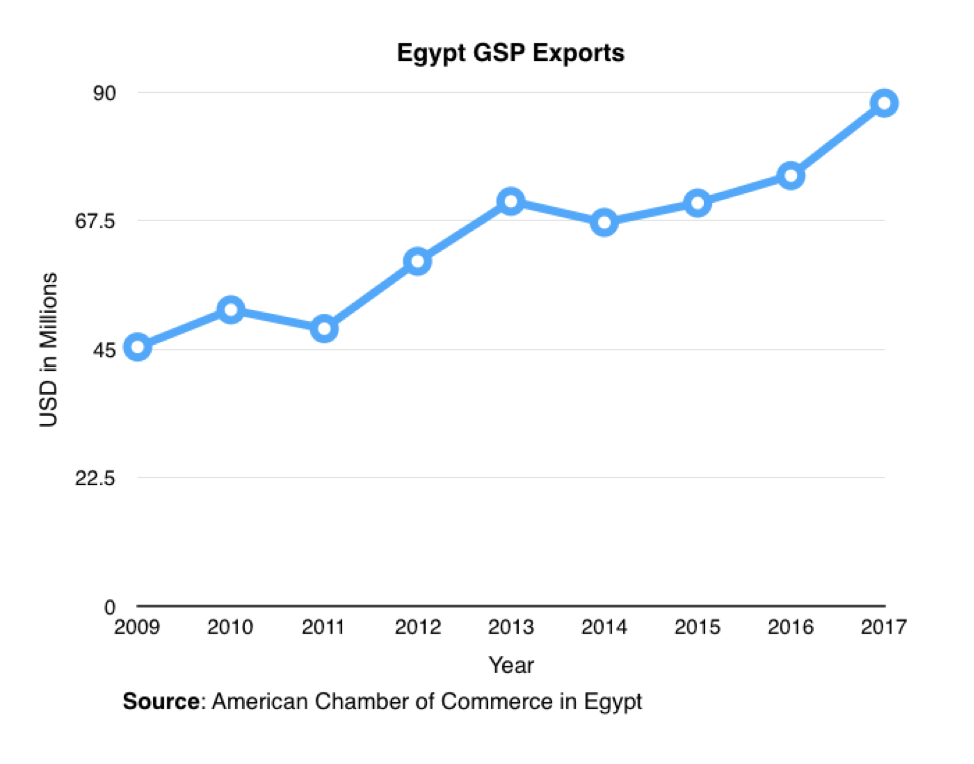

Egypt currently benefits from two initiatives which, while not exclusive to Egypt, are designed to increase a nation’s exports to the U.S. The first is the U.S. Generalized System of Preferences (GSP), a preferential treatment program where certain products may be designated duty-free to the U.S. The second is the Qualifying Industrial Zones (QIZ) initiative, a one-way free trade agreement that allows goods manufactured in designated industrial zones to enter the U.S. duty free, provided the finished goods include a percentage (10.5 percent) of Israeli components.

Discussion over these agreements is lively to say the least. U.S. negotiators consistently maintain that Egypt has not taken full advantage of these two initiatives, particularly the QIZ.

In the case of the GSP, U.S. negotiators familiar with the Egypt file maintain that Egypt has occasionally lobbied for items to be added to the list that were eventually found to be a better fit for other exporters, which then swamped the market. It was also suggested that Egypt look for more niche or luxury markets that would provide the country with an exporting edge.

Exports from the QIZ have totaled $8.97 billion since their start in Egypt in 2005 through 2016, the overwhelming majority of which ($8.93 billion) have been in textiles and garments, with a mere $43 million from food industry exports. 2017 saw exports of $752.7 million, up $11 million from the year before.35 The figures sound attractive but, while there is a discrepancy over the reasons, there is a consensus across all parties that the QIZ could be significantly better utilized.

The majority of U.S. negotiators interviewed for this report maintained that Egyptian exporters are not optimizing their use of what was, essentially, a gift from the U.S. to Egypt. However, Egyptian negotiators and exporters refer to their experience with another view: They maintain that the QIZ started off as a wonderful idea, eagerly taken full advantage of. “The problem was, after that, Israeli exporters realized they had a captive market and just kept raising their prices. Eventually, it became prohibitive for many Egyptian exporters — despite the goods being duty free.”36

Some of the most seasoned negotiators have suggested that it is both a matter of style and substance. The QIZ are overwhelmingly focused on textiles; expanding their content might be one way of utilizing them better, although that is a matter for negotiation between Egyptian and Israeli exporters.

One experienced U.S. negotiator noted that the issue was as much a matter of marketing existing lines as it was of finding new ones. “QIZ products are a joint product between an Arab country and the State of Israel. Supporters of Israel need to know that — it would provide incentive to buy products, whether at an individual or, more importantly, company-wide level. And people who tend toward activism or social good would be eager to purchase products that support peace in the Middle East.”37

A primary concern for the U.S. is market access beyond a simple reduction of tariffs. Individual agricultural exporters and government trade officials have decried what they feel are unreasonable health and sanitation barriers to agricultural imports — issues that they say essentially amount to non-tariff barriers. For instance, according to U.S. negotiators, the agricultural portfolio has become more complicated than it needs to be. Among their concerns is that Egypt has yet to provide a pest assessment risk; an example, they say, of a technical issue that has become politicized.38 For their part, Egyptian negotiators question reciprocity: Egypt is expected to buy U.S. potato seeds, but cannot export those potatoes to the U.S.

The Department of Commerce has repeatedly brought up the fact that the U.S. would expect to have access to procurement, a matter complicated by the fact that Egypt is neither a member nor an observer of the WTO Agreement on Government Procurement.39 Officials at both the departments of State and Commerce have noted that despite many meetings with the Egyptian private sector, actual decision making can be “limited to one person,” and therefore difficult to influence or anticipate.40 Additionally, there can be confusion over the viability of legislation.

An official from the Department of Commerce noted one example: A ministerial decree mandating 51 percent ownership of courier companies, which required new authorization every two years. The decree was later superseded by the new investment law (Law 72 of 2017), but the earlier ministerial decree still exists, resulting in confusion.

Both the State and Commerce departments have emphasized that Egypt has work to do on fundamental International Labor Organization (ILO) standards and environmental agreements. The Department of State goes further, citing the need for “vigorous enforcement of labor standards including freedom of assembly, prevention of child labor and trafficking, and customs and trade facilitation, adoption of U.S. rather than U.N. auto standards, and, of course, enforcement of intellectual property rights provisions.”

It’s a daunting list. Egyptian negotiators say there has been significant progress on many fronts. The country is already working with the ILO’s Better Work Programs and has made progress. Egypt was removed from the ILO blacklist in June 2018. (The Walt Disney Corporation had already lifted its ban on producing merchandise in July 2017. Production had been halted due to a drop in Egypt’s worldwide governance indicators.)41

Egypt has also shown a willingness to compromise on one of the most stringent sticking points in U.S. negotiations: auto standards for American auto exports. Egypt uses U.N. auto standards but, according to a lead negotiator on the Egyptian side, “Egypt is willing to adopt a double standard (U.N. and U.S. Federal Vehicle Standards), despite the copious strain it will place on an already over-burdened bureaucracy. In fact, we have said that if the U.S. were to provide clear guidance on such a double standard, Egypt might be able to provide a response in 60 days.”42

The timeline might be overly optimistic, but it does signal a willingness to compromise that should be taken advantage of. It’s also important to note that FTAs have a proven track record in paving the way for such reform. The prospect of an FTA with the United States helped to forge a domestic consensus for labor law reform in Morocco, spurring reform efforts that had been stymied for more than 20 years. A comprehensive new Moroccan labor law went into effect on June 8, 2004.

“An FTA with the U.S. is not a magic wand, but it will provide vital regional and international buy-in for domestic and international investors, a fact of which Egypt is keenly aware.”

Now what? Recommendations and next steps

U.S. trade negotiators interviewed for this report have repeatedly stressed that for Egypt to fulfill FTA requirements in the immediate future would be “a heavy lift.” The issue of timing has also been pressed home — U.S. trade policy is not currently overwhelmingly in favor of trade liberalization. However, there has also been a recognition that in many ways, Egypt has drawn something of a short straw in terms of timing, since the delays have merely resulted in more intricate and demanding FTAs (the U.S.-UAE attempts at FTA negotiation were paused in 2007 and have yet to resume).

It may be a heavy lift, but there are several compelling reasons to continue to push for a U.S.-Egypt FTA while optimizing the available export initiatives in the meantime.

Notwithstanding the difficulties, the U.S. needs to continue to negotiate for a treaty. The first reason is simple economics: Egypt is a large market with the potential for access to an even larger one. It’s also a market that has demonstrated it is serious about trying to attract and, more importantly, retain, investors. The May 8th, 2018 ruling in the case of ride sharing apps Uber and Careem demonstrated that investors could expect a fair hearing and achieve a victory.43 Considering that the ride sharing companies provide an estimated 50,000 jobs, it was good news all around.

There is also the opportunity cost of not working toward an FTA. “Until we do,” said one U.S. negotiator, “Europe will continue to eat our lunch.”44 This situation will only be exacerbated by Brexit, currently on schedule for Oct. 31st, 2019, so time is very much a factor in these discussions.

The U.S. has repeatedly stated that it wishes to help ensure Egypt’s security and stability. This is a perfectly reasonable aim since if Egypt were ever to stumble, the resulting thud would reverberate throughout the region before rippling across to Europe. One of the biggest threats to Egypt is not extremist violence — although that is not a threat to take lightly — it is the 23.6 percent of the population between the ages of 18 and 29, almost 27 percent of whom are unemployed.45

Egypt’s most urgent issue is its labor force, which is projected to swell to a staggering 80 million by 2028.46 An FTA with the U.S. is not a magic wand, but it will provide vital regional and international buy-in for domestic and international investors, a fact of which Egypt is keenly aware. U.S. businesses, too, must calculate what a market of 80 million individuals might mean for them, either as workers or consumers.

Some U.S. negotiators have said that Egypt needs to compromise. “This isn’t an equal relationship,” said one, “the U.S. market is triple the size of the Egyptian one and there is a disparity in purchasing power.”47 This is the true, of course, and it appears that Egypt already is compromising. It has struggled with labor reform and agricultural goods.

Officials from the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative noted a marked change in attitude during the 2017 Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA) meetings, saying that the Egyptian side appeared significantly more engaged and willing to move matters along. And Egypt has already indicated that it is willing to compromise on a major U.S. requirement: auto standards. The U.S. needs to be able to step forward.

As both sides have repeatedly noted, the negotiations involve a degree of trust and a certain amount of compromise is in the interests of both parties. In much the same way that Egypt has reconsidered its position on some matters, it might be in the interest of the U.S. to prioritize its requirements.

There will, however, be criteria that will not be open to change or compromise. Egypt will need to show that it is serious about Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) protections, for example. Some tariffs will need to be reconsidered. There is a fine line between market protection and protectionism, and Egypt will have to find a balance.

Even under optimal conditions, it could take time for an FTA to be worked out. Until then, Egypt should try to take better advantage of the existing export initiatives available to it. While it is understood that the ultimate goal is an FTA and that these measures are not substitutes for one, their optimization should help mitigate its absence. They should also include a closer re-examination of the GSP. If Egypt is going to lobby for the addition of new items to the list, they should be ones where it is certain that Egypt has a strong comparative advantage.

Finally, it appears that this might be an issue where the private sector can offer advice to the public one. In both countries, the administrations are keenly attuned to the needs of the business communities, and it would be in their interests to play a more active role.

The fact that discussions for an FTA have dragged on makes those discussions more difficult, but no less important. While there doubtless will be difficulties, it is clear that a deep FTA would be beneficial to both countries. The U.S. stands to enjoy positive economic benefits. While they may not be enormous in relative terms, given the size of its economy, they represent very real gains for the U.S. businesses involved. More importantly, there is a significant opportunity cost in letting other countries step up and take the U.S.’ share of the economic pie. Just as importantly, perhaps, a deep FTA would likely provide the U.S. with a clear path to the reform it has consistently demanded that Egypt pursue, in a positive, active manner.

As for Egypt, the economic benefits are more obvious, but the promise of market–backed reform, via a deep FTA which includes services and investment, will be even more desirable. And ultimately, successful economic reform is likely to lead to economic prosperity and greater employment opportunities — a vital requirement for a country where poverty and lack of employment have been linked to radicalization and terrorist recruitment. The political and economic conditions for an FTA are more auspicious now than they have been in decades, between a trade-focused U.S. administration that appears willing to move toward warmer relations and an investment-focused Egyptian leadership that has thrown all of its weight behind attracting and retaining FDI.

An FTA presents clear advantages for both sides, and it is important to move forward and grasp the opportunity. Trade opportunities must be taken up by someone; the question for Egypt and the U.S. is whether they wish to take them up together, or with other partners.

Endnotes

1. United States Census Bureau www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/ c7290.html

2. The State of African Cities 2018 – The geography of African investment (UN Habitat Report, 2018) unhabitat.org/books/the-state-of-africancities-2018-the-geography-of-africaninvestment/.

3. Meredith Broadbent, The Role of FTA Negotiations in the Future of US-Egypt Relations (Center for Strategic and International Studies, December 2011).

4. Interview with author

5. “Al-Sisi, Xi Jinping Sign Five Cooperation Agreements between Egypt, China.” Daily News Egypt, September S, 2018. ww.dailynewssegypt.com/2018/09/02/ al-sisi-xi-jinping-sign-five-cooperationagreements-between-egypt-china.

6. Interview with former Minister of Finance Ahmed Galal.

7. United States Census Bureau www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/ c5081.html

8. Ibid. www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/ c7290.html

9. Alia Mamdouh, Director of Macro and Strategy, Beltone Financial, Bloomberg interview (August 28th 2018) www.bloomberg.com/news/ videos/2018-08-28/egyptian-pound-toremain-stable-beltone-s-mamdouh-saysvideo.

10. www.poundsterlinglive.com/bestexchange-rates/us-dollar-to-egyptianpound…

11. El-Tablawy, Tarek. “‘Rate Cut on the Horizon’ Sparks Investor Rush for Egypt’s Pound.” Bloomberg, February 14, 2019. www.bloomberg.com/news/ articles/2019-02-14/rate-pause-nears-ayear-in-egypt-with-inflation-set-for-liftoff.

12. www.imf.org/en/Countries/EGY

13. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2019/04/05/Arab-Republic-…

14. International Monetary Fund Country Report, Egypt, January 22nd, 2018. www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/ Issues/2018/01/22/Arab-Republic-ofEgypt-2017-Article-IV-ConsultationSecond-Review-Under-theExtended-45568.

15. Ahmed Galal and Robert Lawrence, Egypt-US and Morocco-US Free Trade Agreements, Egyptian Center for Economic Studies, (Working paper), No. 87, July 2003.

16. Ahmed Galal and Robert Z. Lawrence, Anchoring Reform With A US-Egypt Free Trade Agreement, Peterson Institute, May 2005.

17. Mathew Lee, US to release $1.2 billion in military aid to Egypt, AP News, September 7, 2018.

18. “Al-Sisi, Xi Jinping Sign Five Cooperation Agreements between Egypt, China.” Daily News Egypt, September S, 2018. ww.dailynewssegypt.com/2018/09/02/ al-sisi-xi-jinping-sign-five-cooperationagreements-between-egypt-china.

19. Ahmed Galal and Robert Lawrence, Egypt-US and Morocco-US Free Trade Agreements, Egyptian Center for Economic Studies, (Working paper), No. 87, July 2003.

20. Egypt court orders re-trial of NGO foreign funding case, Reuters, April 5, 2018. af.reuters.com/article/ commoditiesNews/idAFL4N1RI3I8

21. Interview with author.

22. Full text of Law 72 of 2017 www.gafi.gov.eg/English/eServices/ Documents/LAw72-english.pdf

24. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2019/01/weodata/index.aspx

25. Nadine Awadalla and Patrick Werr, “Egypt targets narrower budget deficit of 8.4 pct in 2018/19 - minister”, Reuters, September 4, 2018. www.reuters.com/article/egypteconomy/update-1-egypt-targetsnarrower-bud…;

26. “Egypt’s finance ministry targets reducing budget deficit to 7% in 2019/2020,” IFP Info, November 15, 2018. www.ifpinfo.com/egypts-financeministry-targets-reducing-budget-deficitt….

27. www.tradingeconomics.com/egypt/ foreign-exchange-reserves

28. Netty Idayu Ismail and Ahmed Feteha, “Traders seeking refuge from volatility will find it in Egypt,” Bloomberg, August 15, 2018. www.bloomberg.com/news/ articles/2018-08-15/traders-looking-forrefuge-from-volatility-will-find-it-in-egypt.

29. Nihal Samir, “Russian investments in Egypt reach over $8bn within next 2-3 years: Ezz,” Daily News Egypt, October 16, 2018. www.dailynewssegypt.com/2018/10/16/ russian-investments-in-egypt-reach-over8bn-within-next-2-3-years-ezz.

30. The State of African Cities 2018 – The geography of African investment (UN Habitat Report, 2018). www.unhabitat.org/books/the-state-ofafrican-cities-2018-the-geography-o….

31. Trade Report Q4 2017, N Gage Consulting, 2017. www.ngage-consulting.com/downloads/ trade_reports/Trade%20Report%20Q4%20 2017.pdf.

32. Meredith Broadbent, The Role of FTA Negotiations in the Future of US-Egypt Relations (Center for Strategic and International Studies, December 2011). 23

33. Ibid.

34. Interview with Department of Commerce.

35. Ahmed Sabry, Egypt’s exports from QIZs at $752m, Daily News Egypt, February 20, 2018. dailynewsegypt.com/2018/02/20/ egypts-exports-qizs-752m.

36. Interview with author.

37. Interview with author.

38. Interview with author.

39. Text of WTO Agreement on Government Procurement.

40. Interview with author.

41. “Walt Disney Company Lifts its Ban on Having Its Merchandise Manufactured in Egypt,” Enterprise, July 3, 2017. www.enterprise.press/ stories/2017/07/03/the-walt-disneycompany-lifts-ban-on-having-itsmerchandise-manufactured-in-egypt.

42. Interview with author.

43. Daniel Mumbere, “Egypt enacts law to regulate Uber, introduces data sharing requirements,” Africa News, May 8, 2018. www.africanews.com/2018/05/08/ egypt-enacts-law-to-regulate-uberintroduces-data-sharing-requirements.

44. Interview with author.

45. “23.6% of Egypt’s population are youths,” Ahramonline, August 12, 2017. english.ahram.org.eg/ NewsContent/1/64/275212/Egypt/ Politics-/-of-Egypt%E2%80%99spopulation-are-youths-CAPMAS.aspx.

46. David Lipton, Inclusive Growth and Job Creation in Egypt (IMF speech May 5, 2018).

47. Interview with author

Research support

Research support provided by Alena Shalaby

Photos

Photo 1: Construction of the financial district, undertaken by China State Construction Engineering Corporation in the new administrative capital, some 50 km east of the capital Cairo, on March 7, 2019. (Photo by PEDRO COSTA GOMES/AFP/Getty Images)

Photo 2: The Nile and buildings including the Nile City Towers on September 24, 2017 in Cairo, Egypt. (Photo by David Degner/Getty Images)

Photo 3: Oil rig helipad and support ship in the Gulf of Suez. (Photo by Giles Barnard/Construction Photography/Avalon/Getty Images)

Photo 4: German Economic Affairs and Energy Minister Peter Altmaier (C) talks with Egyptian Minister of Investment and International Cooperation Sahar Nasr (R) and Egyptian Minister of Industry, Trade and Small Industries Amr Nassar, during the 5th Egyptian-German Business Forum. (Photo by Omar Zoheiry/picture alliance via Getty Images)

Photo 5: A view of Cairo from above including the Zamalek Sofitel, boats on the Nile, and the bridges at sunset on September 24, 2017 in Cairo, Egypt. (Photo by David Degner/Getty Images)

Photo 6: A picture taken on July 29, 2018 shows a worker checking textiles on a machine at the Marie Louis textile clothing and textile factory in the 10th of Ramadan city, about 60 kms north of Cairo. (Photo by KHALED DESOUKI/AFP/Getty Images)

Photo 7: A picture taken on May 5, 2019, shows the road leading to the newly opened tunnel, which runs under the Suez Canal, in Ismailia city east of Cairo. (Photo by KHALED DESOUKI/AFP/Getty Images)

Photo 8: A street vendor sells snacks to drivers stuck in a traffic jam backdropped by advertising billboards. (Photo by Samer Abdallah/picture alliance via Getty Images)

Photo 9: Egyptian workers assemble vehicles at a BMW factory on May 29, 2011 in 6th October City, Egypt. (Photo by Peter Macdiarmid/Getty Images)

Photo 10: Egyptian workers leave the Misr spinning and weaving factory in Mahala, 120 kms north Cairo, after a day's work on April 8, 2014. (Photo by MAHMOUD KHALED/AFP/Getty Images)

Photo 11: Cargo ship transits the Suez Canal, Egypt. (Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images)

About the author

Mirette F. Mabrouk is an MEI senior fellow and director of the Institute’s Egypt Studies program. She was previously deputy director and director for research and programs at the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East at the Atlantic Council. An Egypt analyst who was previously a nonresident fellow at the Project for U.S. Relations with the Middle East at the Brookings Institution, Mabrouk moved to D.C. from Cairo, where she was director of communications for the Economic Research Forum (ERF). Formerly associate director for publishing operations at The American University in Cairo Press, Ms. Mabrouk has over 20 years of experience in journalism. She is the founding publisher of The Daily Star Egypt, (now The Daily New Egypt), at the time, the country’s only independent English-language daily newspaper, and the former publishing director for IBA Media, which produces the region’s top English-language magazines. She recently authored “And Now for Something Completely Different: Arab Media’s Own Little Revolution,” a chapter in the new book on the Arab transitions, Reconstructing the Middle East

About the Middle East Institute

The Middle East Institute is a center of knowledge dedicated to narrowing divides between the peoples of the Middle East and the United States. With over 70 years’ experience, MEI has established itself as a credible, non-partisan source of insight and policy analysis on all matters concerning the Middle East. MEI is distinguished by its holistic approach to the region and its deep understanding of the Middle East’s political, economic and cultural contexts. Through the collaborative work of its three centers — Policy & Research, Arts & Culture and Education — MEI provides current and future leaders with the resources necessary to build a future of mutual understanding.