Summary

The following article addresses the question of how the Middle East might develop in the coming decade. Long-term and detailed strategic predictions are a thankless task and are often doomed to failure. One need look no further than the World Economic Forum’s report on global risks published in January 2020.1 It assessed the likelihood of an infectious disease outbreak or instability in the global energy market as relatively unlikely, even though both ended up happening less than two months after the report’s publication.

Therefore, this article refrains from attempts at prophecy but deals instead with “thinking about the future.” It opens with an analytical framework for scenario development, supplemented by “trends impact” and “horizon scanning.” The second section studies “the futures of the past,” in terms of what we might learn about the pitfalls of future projection and scenario-building from those outlining possible futures for 2020 from years past. Then, on the basis of the first two sections, four scenarios elaborate some distinctly different pathways that the Middle East might take to 2030. Finally, the article concludes with several key takeaways for Israeli decision makers.

Authors' note: We would like to thank Mr. David Shedd, former acting director of the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency, Mr. Elisha Stoin of Israel’s Ministry of Intelligence, and Mr. Steven Kenney of the Middle East Institute for their important advice and thoughtful input on the monumental task of thinking about the future. Any errors in this work are the authors’ alone.

I. Understanding Analytical Tools for Thinking About the Futures

The further one seeks to gaze into the future, the less useful forecast techniques become. The forecast aims at “calculating or predicting (some future event or condition) usually as a result of study and analysis of available pertinent data.”2 But the distant future is hardly a singular event. Rather, it is a landscape created through a combination of change and continuity, and so there is a high probability of departing from at least some currently dominant trends. Accelerating changes in recent years, including massive increases in the amount, variety, and tempo of information available, the rate of technological advances, climate change, and the interconnectivity and interdependencies between distant geographical locations further increase the level of uncertainty regarding the future.

Scenario development is one of the most popular methodologies to investigate the future, and various methods have been developed to build and map scenarios.3 The basic concept evolved from business practitioners, with the most famous method being the matrix introduced by Royal Dutch Shell and refined later in Global Business Network (GBN). The 2x2 matrix method lays down a structured process to develop scenarios.4 Two variables are identified as having the strongest potential impact on the future. The matrix of four scenarios is derived from combinations of the extreme values for those two factors.

The factors influencing the future can be identified through methods known as “trends impact” and “horizon scanning.”5 “Trends impact” focuses primarily on identifying existing and continuing currents that could influence the future. “Horizon scanning” focuses on emergent issues that might gain strength in the future and lead to systemic change. It involves the systematic detection and identification of weak signals6 and emerging trends and considers their potential to become triggers of major change. The trigger can be external, demographic, technological, ideological, or any other potential development capable of having a major impact if the weak signal were to become markedly stronger.

There is some criticism about scenarios methods: there are many pitfalls in developing them,7 and the employment of different techniques can lead to diverging future constructs.8 The latter point is actually as much a benefit as a criticism, since the objective of scenario exercises is to stimulate thinking about a diverse range of possibilities. Nevertheless, scenarios are an indispensable and creative mechanism that produces what is known as “interesting research” 9 (that which is innovative and more likely to produce learning), broadens thinking about future possibilities, and helps to prevent group-think. Development of scenarios is only a starting point for strategic planning, and the latter issue is not dealt with in this article.

The OECD suggests that, “scenarios are tools created to have structured conversations and analysis of the challenges and opportunities that the future may bring.”10 Kosow and Gassner explain that, “scenarios have no claim to reality and therefore do not provide a ‘true’ knowledge of the future; rather, they merely supply a hypothetical construct of possible futures on the basis of knowledge gained in the present and past — a construct which includes, of course, probable, possible and desirable future developments.”11

Beyond the distinct methods, it is also worth keeping in mind that different vantage points will produce different scenarios. As a “neutral” scenario could not be focused, readable, and useful if it lists every development in a given country or region even over the course of a single day, the focus and priorities of the scenario must be limited in scope and defined by the perspective from which it is written. Because the authors of this paper are researchers at Israel’s Institute for National Security Studies, the scenarios have been developed from an Israeli point of view.

Successful implementation of this approach by the Government of Israel would require four key ingredients: 1) identifying potential developments and trends, 2) assessing their relevance to Israeli national interests, 3) determining the potential array of required responses, 4) and implementing recommendations that leave Israel better prepared for the range of possible futures.

II. The Futures of the Past

Before presenting four scenarios for how the future of the Middle East might develop, it is worth considering how others had thought about the present (2020) when it was still the future. This can be instructive in highlighting the challenges of scenario-building that subsequent efforts by the Government of Israel or others should take into account or even “correct for” when outlining and evaluating possible futures. “Mapping the Global Future,”12 which was published in 2004 as part of the 2020 Project by the U.S. National Intelligence Council (NIC), was used as a case study.

First, what quickly becomes apparent in assessments of the future is the tendency of authors, regardless of when they are writing,13 to include assumptions that their subject is in a unique state of flux. Our sense is that such an assessment would be appropriate for the current moment due to the rising uncertainty resulting from COVID-19, globalization, a shifting political order, and quickening pace of economic and technological change. But scenarios built only around such an assumption pay insufficient attention to any number of factors that are more representative of continuity and are potentially just as impactful as that which is changing. Examples of trends present today that have not changed much since the NIC report was published more than 15 years ago include the power of the U.S. dollar in the global financial system and the strong global commitment to prevent countries in the Middle East from acquiring nuclear weapons (and none have nuclearized since the publication of the report). Given the tendency to underestimate continuity, in moments when radical change feels imminent it is worth recalling that much often remains the same over time.

Second, when thinking about the future, it is important to consider the duality of developments. For example, the NIC’s 2004 report notes that one uncertainty for the future is the “Extent to which [Internet] connectivity challenges governments.” It is now clear that despite the short period in which social media exclusively enabled the public to organize against regimes, the connectedness and “smartness” of daily life — from iPhones to cashless payment to apps — has since evolved into a force multiplier that on balance favors totalitarian governments. What this suggests is the importance of considering in scenarios, or in the analysis of the implications of scenarios, what we might call “counter-trends” or “anti-trends” that could emerge instead of, or even alongside, an expected trend.

Third, to quote Shakespeare, “there is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so.” The complexity of thinking about the future is not only about how events will develop, but how those in the future will assess them. Increasing U.S.-China economic cooperation is an example of the NIC anticipating how things would develop but not how they would be evaluated in 15 years’ time. The “Davos Scenario”14 presented in the 2004 report is viewed as fairly optimistic and mutually beneficial — in fact one of the concerns cited that caused “sleepless nights” was financial troubles for China.15 Nonetheless, the shift of the political consensus in the U.S. from a Liberal to a more Realist foreign policy viewpoint has made this somewhat optimistic outcome appear quite threatening when viewed through the lens of relative U.S. decline.16 Scenario developers and analysts would do well to consider: under what future conditions would the benefits and risks of our scenarios be perceived differently than we view them today? How should that influence how policymakers today respond to or prepare for the scenarios?

Fourth, the weight assigned to specific issues reflects the particular viewpoint at the time of publication but the relative weight of issues is liable to shift over time. In 2004, given the deep U.S. involvement in two wars in the Middle East and the then-recent experience of the 9/11 attacks, the NIC report described political Islam as having “significant global impact.” While there can be little doubt that more radical currents of Islam maintain some continued impact, their lack of broader appeal to either populations or states make them negligible factors in the context of the global order. It is important when projecting multiple scenarios to weigh key variables differently in the range of scenarios.

Fifth, blind spots are inevitable, and experts used to looking outward may run the risk of neglecting developments in their own country, though the latter are certainly no less important. For example, the NIC correctly noted that globalization could lead to the rise of populism and pointed to Latin America as the likely place for that to emerge. While it is true that populism emerged in Latin America, its appeal to those left behind by globalization proved to be global in nature, including — unexpectedly though perhaps more importantly — in the U.S. It is often valuable for this reason to get feedback and inputs from a diverse group on scenarios as they are being formulated. Doing so helps ensure against missing potentially important implications that the scenario developers can overlook if they are too close to the subject matter.

The aim of examining “futures of the past” is certainly not to point out what some might view as errors. In fact, the NIC presented many valuable insights that proved prescient about events that would take place years later: the factors leading to the “Arab Spring,” the non-linear path of globalization, and the decline of al-Qaeda as well as the rise of ISIS. Rather, we hope that reviewing how the futures of the past were perceived when compared with how they developed will be instructive in formulating clearer guidelines for how to think about the future.

“Given the tendency to underestimate continuity, in moments when radical change feels imminent it is worth recalling that much often remains the same over time.”

III. 4 Scenarios for Middle East 2030

Drawing up different scenarios has been described by Brig. Gen. (ret.) Itai Brun17 as helpful for thinking about possible futures, facilitating decisionmakers’ consideration of different ideas about policy, the exercise of power, and military buildup, and useful for governments seeking to prepare themselves for the future.18

The current realities worldwide and in the Middle East highlight the importance of preparing for the next decade in the region through the lens of scenarios rather than straightforward predictions. The COVID-19 crisis strains the already tenuous ability to develop long-term predictions, as even deciphering the present reality remains a challenge and basic assumptions regarding the factors shaping the future have been called into question. Since the start of the crisis in early 2020, economic institutions have frequently updated their forecasts based on projected energy use and the global economic recovery.19 Political, military, and social aspects of regional dynamics in the Middle East remain volatile.

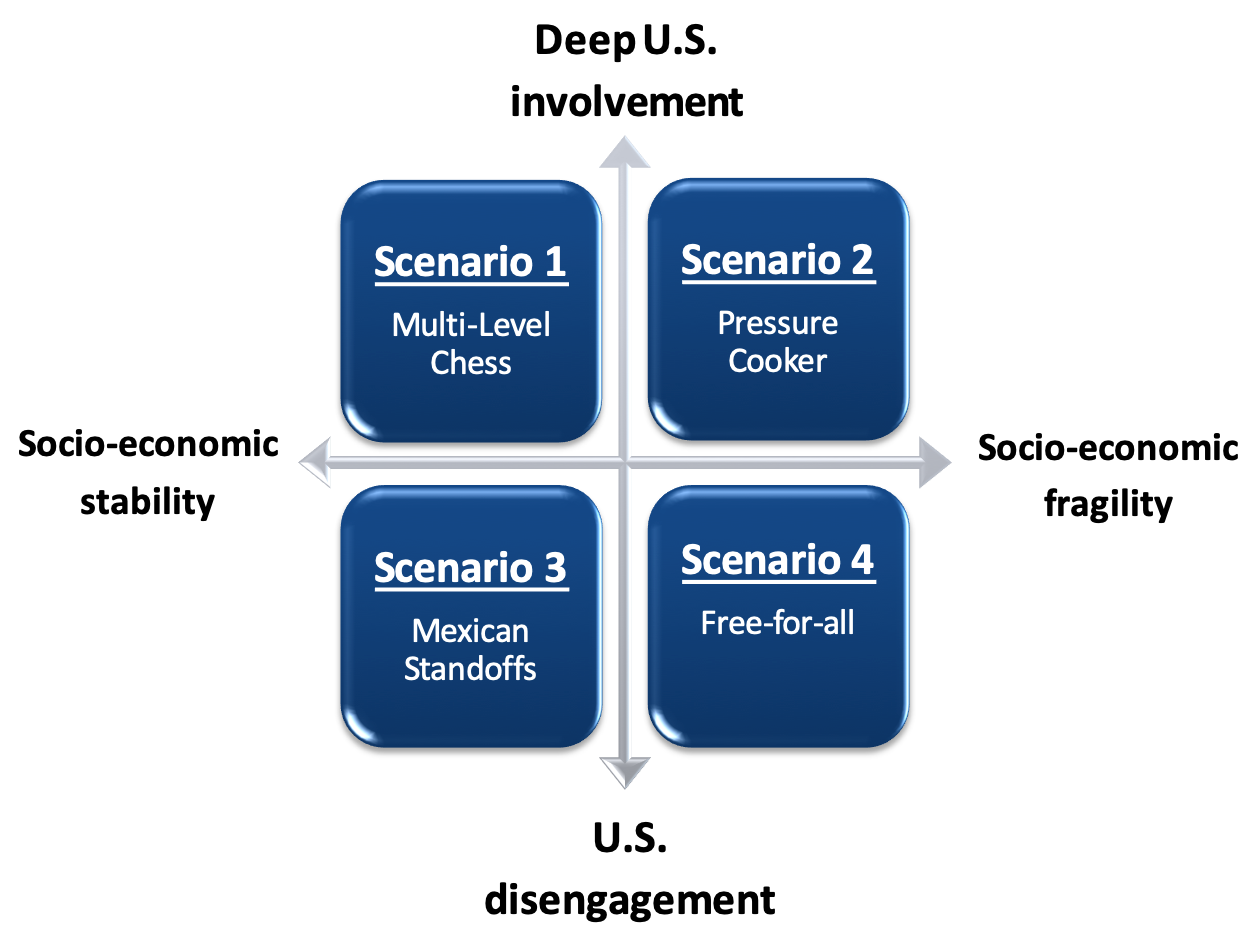

With that in mind, the authors sought to develop four scenarios of “possible futures” of the Middle East in 2030 from the Israeli point of view and based on the 2x2 matrix methodology. The scenarios are exploratory, rather than predictive or normative,20 meaning that they aim to answer the question of what can happen rather than what will or what should. This process included conducting a structured analysis of persistent trends and possible game-changers, prioritizing them, and agreeing on the two variables from which the two axes of the scenario generating matrix were derived.

What we determined as the most important and persistent trends to consider, which appear poised to influence the Middle East over the next decade, are:

a) The Decline of Unipolarity: The results of this ongoing global transition from unipolarity to a bipolar (U.S.-China) or multipolar (U.S.-China-Russia) world will include: growing challenges to the existing international system;21 intensification of great power competition and its projection into the MENA region;22 U.S. efforts to reduce its military footprint in the Middle East in favor of the “Pivot to Asia”; an expanded Chinese footprint around the globe (mainly through commerce and infrastructure projects); and Russian attempts to reestablish itself as a powerbroker in the region.

b) Regional Competition: Middle Eastern powers are and will continue to be engaged in intense competition for influence in third countries, including Syria, Yemen, Lebanon, Libya, and other African countries. Blocs that have sought to compete include: the Iran-led radical Shi’a coalition, the Turkey-Qatar Islamist-oriented alliance, and the United Arab Emirates-Saudi Arabia status-quo axis. However, it is worth noting that because these camps are composed of individual actors with interests that do not always entirely overlap with one another, hedging and limited inter-camp cooperation occur when interests dictate.

c) Ideological Volatility: Increasing political repression in the region and the diminishing window for achieving non-violent political change may cause populations to look toward more radical and violent ideologies. While the Muslim Brotherhood’s Islamist wave appears to be on the ebb since President Mohamed Morsi’s overthrow in 2013, it is possible that some other form of radical Islam or even some altogether different radical ideological current will rise.

d) Proliferation of Dangerous Technologies: The unraveling of arms control agreements increases the risk of nuclear proliferation,23 while the largely unregulated proliferation of precision-guided munitions has enabled the emergence of strategic non-nuclear threats in the region.

e) Growing Demographic Pressures: The population of the Middle East is expected to rise by about 20%,24 to 581 million people, by 2030. According to a UNICEF report entitled “MENA Generation 2030,”25 the youth bulge resulting from the relatively high rate of fertility in the region will create additional strains on the state and, barring a rapid increase in investment (which does not appear forthcoming), could lead to an 11% increase in youth unemployment and an additional 5 million children out of school.

f) Societal and Economic Prospects: There are no indications that provide reason to expect a significant improvement in the fundamental social-economic problems of the Middle East that contributed to the political unrest in 2010 and onward;26 there remains a serious relative lack of human capital and the public’s faith in government institutions continues to decline.27 Attempts at internal economic, social, and political reforms throughout the region are undercut by entrenched elites and ingrained practices. Therefore, it is difficult to imagine that the next decade will see significant progress in closing those gaps, and some of the world’s most fragile states that are situated in the Middle East might become further destabilized or involved in inter-state conflicts.28

In addition, the regional economies will face considerable challenges in recovering from the COVID-19 crisis, which inflicted severe damage on key industries. After the price collapse in April 2020, petrostates will find themselves dependent on a volatile (at best) oil market that will prove the determining factor for whether or not they will be able to balance their annual budget.

g) Environmental Problems: Climate change will likely intensify water scarcity in an already water-poor region,29 30 bring food shortages, spur refugee crises, and possibly make some areas in the Arab Gulf uninhabitable by 2050.31

h) Rapid Technological Change: Advances in technologies such as AI will allow for deeper incursions by authoritarian regimes into the private lives of citizens (“digital authoritarianism”) and will result in more unmanned or even autonomous systems on future battlefields.32

In addition to these major trends, we see a number of potential “game-changer” developments that could emerge over the next decade, partly influenced by the trends but also partly independent of them. The list of potential gamechangers includes developments such as: leadership changes within existing regimes, shifting partnerships/rivalries, internal upheavals leading to regime change, military interventions by global/regional powers into crises, the end of military conflicts and the terms of their conclusion, the acquisition of nuclear weapons by a state or states that did not previously possess them, dramatic technological developments that shift the balance of economic or military power, and natural disasters that inflict major human or infrastructural losses.

The two major variables that the authors used to map out the “potential futures,” due to their direct impact or correlation with numerous trends listed above, are as follows:

1) U.S. readiness to play a strong and shaping role in the Middle East, including the investment of resources, manpower, and political capital to support its allies and confront destabilizing actors. This variable is strongly correlated with (a) the future of competition between the great powers, (b) rivalry among regional powers in MENA, (c) counter-terrorism, and (d) nuclear proliferation. Further distraction of the U.S. from Middle Eastern issues will provide greater room for Russia and China to maneuver, reduce the military and political constraints on other actors in the region like Turkey and Iran, and potentially allow for the proliferation of nuclear technologies; deeper U.S. involvement may rein in regional struggles and diminish the probability of the appearance of a new nuclear power in the region. As for counterterrorism, it has served as a driving force behind American involvement in a variety of theaters including Afghanistan, Syria, and Iraq, so the regrouping or decline of jihadist or other transnational militant groups from the region could factor into the level of U.S. engagement in the Middle East.

2) Socio-economic stability in MENA countries is strongly correlated with (e) demographic pressures, societal and (f) economic prospects, (g) environmental problems, and (h) technological change. When looking ahead, the continued decline of energy revenues and growing populations could lead to the fracturing of existing social contracts between governments and citizens, potentially involving reduced use of incentives or subsidies and greater use of force to ensure regime survival. The COVID-19 crisis and environmental problems are not necessarily the decisive factors in the region’s economy, but they will likely add economic pressures on states and expand existing socio-economic gaps. Changes in the socio-economic stability of states in the region may redraw the map of regional and even extra-regional alliances.

The intersection between the two variables produces the following four scenarios:

- Multi-Level Chess: Deep U.S. involvement in a relatively stable region.

- Pressure Cooker: Deep U.S. involvement in an unstable region.

- Mexican Standoffs: U.S. disengagement from a relatively stable region.

- Free-for-all: U.S. disengagement from an unstable region.

After determining the four scenarios, we have added some “meat” to the skeletal scenarios through backcasting. The four scenarios meet the four benchmarks for scenario development:33 they are plausible, relevant, divergent, and challenging, and are viewed from a singular — in this case Israeli — perspective.

They are intended to highlight the reality that over the course of the next decade Israel’s strategic environment could undergo fundamental changes. This could be the result of the rising importance of factors that are today considered marginal, or chain reactions resulting from “game changers.” The scenarios are intentionally replete with details in order to provide greater texture and encourage lively conversation and debate about the future; they are intended to both reflect and to test reality. It is worth noting that not all scenarios include the same “building blocks,” as for instance Lebanese Hezbollah is noticeably absent from some of them, because the idea is to highlight the unique challenges of a particular scenario rather than to recreate the decade ahead in all its complexity.

Learning from the best practices of those who have done work in this vein before us, we concluded that it would be foolhardy to try to calculate the likelihood of any particular event or scenario. In the words of former NIC Chairman Joseph Nye Jr., “The job, after all, is not so much to predict the future as to help policymakers think about the future. No one can know the future, and it is misleading to pretend to.”34 Or as the late political scientist Herman Kahn of the RAND Corporation put it succinctly, “The most likely future isn’t.”35

“Climate change will likely intensify water scarcity in an already water-poor region, bring food shortages, spur refugee crises, and possibly make some areas in the Arab Gulf uninhabitable by 2050.”

Scenario #1: Multi-Level Chess

The swift development of a COVID-19 vaccine and international efforts to produce and distribute it leads to a quick recovery of the global economy along with renewed demand for oil and gas. Russia works together with Saudi Arabia to expand and strengthen OPEC+ in order to maintain high energy prices. The petrostates in the Middle East continue to provide financial support for the poorer states in the region.

The U.S. administration is committed to tackling Middle Eastern challenges through proactive diplomacy. One of Washington’s key aims in the Middle East is limiting Chinese and (secondarily) Russian influence. U.S. efforts to repel the expansion of its great power rivals lead it to resume close cooperation with Turkey, which returned its S-400 surface-to-air (SAM) batteries to Moscow, and stopped the flow of Russian gas (having good substitutes from Azerbaijan, liquefied natural gas, and newly discovered internal resources). It has also cancelled the contract for Russia to build it nuclear reactors. Sophisticated offensive arms are sold to Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries by Washington in order to discourage the purchase of Chinese alternatives and deter Iran.

In return for drifting away from Russia, Turkey receives Washington’s help in realizing its aim of becoming a Mediterranean energy hub. Due to U.S. pressure, Israel, Lebanon, Cyprus, Greece, and Egypt are pushed into starting construction on a network of gas pipelines to Turkey, from where the gas will then be transported to Europe. Within the context of this arrangement, a peace agreement is signed on the division of Cyprus, as well as the territorial waters in the eastern Mediterranean (Greece holds onto its islands, while Turkey significantly expands its exclusive economic zone).

Moscow’s standing in the region is severely undermined when the U.S. convinces President Bashar al-Assad of Syria to cancel the lease of military bases to Russia and send uniformed Iranian forces home. In return, Damascus receives recognition of its control over Syrian Kurdish territories (albeit granting local bodies some autonomy), an invitation to return to the Arab League, and some Gulf funding for Syrian reconstruction efforts. Turkey is pressured to evacuate northwest Syria in exchange for security guarantees that the regime will rein in Kurdish separatist activity. Israel is a staunch supporter of this process, but as a condition for its implementation had to agree to end its airstrikes in Syria. Although the Iranian presence in Syria is initially reduced, it is gradually reconstituted in the years that followed and Israel found itself unable to militarily intervene in order to prevent that.

Following King Salman’s passing in 2021, there is an attempted palace coup d’état in Saudi Arabia in which Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MbS) is assassinated and the Iranians seize the opportunity to foment large-scale protests in the predominantly Shi’a eastern regions of the country. However, MbS’s “camp” emerges victorious fairly quickly from the power struggle that ensued, and his younger brother, Deputy Defense Minister Khaled bin Salman (KbS), assumes the throne.

The newly crowned King Khaled seeks to change the kingdom’s priorities by reducing its regional involvement and focusing the bulk of its resources on domestic modernization. The change in leadership also allows for an extended cease-fire in Yemen and ultimately a Saudi withdrawal from that costly conflict. At the insistence of the U.S., simmering tensions within the GCC are diminished when Saudi Arabia and the UAE take public and substantial steps to boost economic and political ties with Qatar in exchange for Doha cutting back its ties to the regional Islamist camp led by Turkey.

A broader Saudi-Iranian détente is then mediated by the sultan of Oman. As part of this process, Iran agrees to the full integration of Shi’a militias into Iraq’s armed forces, though Tehran retains considerable indirect levers of influence in the country.

Following the escalation of a dispute between Saudi Arabia and Pakistan regarding a number of core issues for both countries, including the status of Kashmir, Riyadh reduces the number of Pakistani workers allowed into the kingdom. Laborers from poorer countries in the Arab world are then offered work visas to Saudi Arabia to supplement the foreign workforce and the volume of remittances to countries such as Egypt and Yemen increases.

The relative prosperity in the region due to continued high oil prices and remittances from the Gulf leads Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE to invest in more advanced and intrusive surveillance technology. In addition to jihadists, the primary targets of the surveillance by the security forces are Muslim Brotherhood affiliates and liberal human rights activists. The U.S. government continues to speak publicly about the ideals of human rights and democracy, including in ways that pertain to the Middle East, but in practice applies minimal pressure on Arab rulers to adopt those principles.

In 2022, the death of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and his unexpected succession by Hassan Rouhani allow for a new interim agreement: the U.S. is to lift some sanctions, while Iran freezes its nuclear program and reduces its malign activity in the region. At Iran’s urging, Hezbollah agrees to Lebanon’s settling of the maritime boundary dispute with Israel in order to develop the Lebanese gas fields — though the group maintains its hold on political power and arms.

Iran’s reformists then win a decisive victory in the parliamentary elections of 2024, which facilitates the signing of a new and more comprehensive nuclear agreement the following year. The new deal requires Iran to relinquish all enrichment capabilities indefinitely and restrict its missiles’ range to 500 kilometers. These concessions are granted in exchange for broadening Iran’s civilian nuclear program (construction of five reactors paid for by an international consortium) and the lifting of all sanctions.

Due to U.S. and UAE pressure, Israel assents to Mohammed Dahlan’s assumption of control over the Palestinian Authority (PA) after Mahmoud Abbas’s death in 2023. Dahlan’s efforts to regain control of Gaza lead to several rounds of fighting between the PA and Hamas, and with the help of Israel and Egypt, by 2024 Dahlan pressures the Hamas leadership to flee to Turkey.

Israel’s involvement in the intra-Palestinian struggle arouses negative sentiments toward Israel in the Arab world in general, and in Saudi Arabia in particular, where the political and religious establishments were already at odds regarding modernization. The Saudi government tries to appease the internal opposition by supporting the Palestinians against Israel and pushing the Gulf states to reduce their public displays of normalization with Israel. By 2025, Dahlan brings U.S. and Emirati pressure to bear on Israel to promote a peace agreement. When the talks falter and then implode, the result is a major escalation of fighting between Israel and the Palestinians that then leads to the cutting of diplomatic ties between Israel and Arab states, including longstanding partners Egypt and Jordan.

Throughout the years 2026-27, Turkey and the Gulf states take steps to undermine the success of the new nuclear deal due to Iran’s continued meddling in the region. During this time, Iran gravitates away from Europe and toward the orbits of Russia and China. In 2028, the reformists lose the elections in Iran as their diplomatic endeavors failed to significantly improve the country’s economic situation. In 2030, Iran declares that the treachery of the West and the relentless pressure on the regime have left Tehran with no choice but to develop nuclear weapons — and it carries out a successful underground test in the country’s eastern desert region.

This scenario shows that strong American involvement in the region alone might not guarantee that Israel’s security interests are protected. In addition, greater internal stability could make key actors in the Middle East more assertive toward Israel. Also, Russia’s regional standing is largely guaranteed by the Assad regime, limiting its room to maneuver in Syria. Finally, hard-won negotiated assets such as the Abraham Accords or a “better deal” with Iran might disintegrate quickly because of the complexity and inter-connectivity of regional security problems.

Scenario #2: The “Pressure Cooker”

Washington slightly reduces its military presence in the region but still maintains significant forces in the Gulf, and to a lesser extent in Iraq and Syria. In parallel, the U.S. encourages the regional actors to resolve their security challenges on their own, which has the added economic benefit of increasing weapons sales to regional states. The key U.S. objectives in the Middle East are to prevent the emergence of a power vacuum that will be filled by Russia or China and to make sure that regional problems don’t “spill over.” Also, there is a strong demand from Washington for Middle Eastern allies to demonstrate progress toward democratization.

The global economic recovery lags because of setbacks in bringing an end to the COVID-19 health crisis. It only begins to recover slowly in early 2023, and energy prices are expected to remain lower than 2019 levels for the foreseeable future.

The decline in energy revenues forces the Gulf states to reduce their economic support to the poorer Arab states, in particular Egypt. As a result, several of President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi’s megaprojects are cancelled and Egypt’s connection to the other members of the Arab Quartet (Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Bahrain) erodes. China and Russia step in to increase their support for Egypt in various ways: the provision of COVID-19 vaccines for free or on favorable terms, replacement of the UAE as the primary funder of infrastructure projects, and assistance to President el-Sisi by enhancing his digital repression capabilities. Russia, through its security services and military contractors, cooperates with Egypt in Libya and other areas of interest. China signs an agreement with Field Marshall Khalifa Hifter to operate the Benghazi port. Russia completes construction of a naval and air bases in Sudan and gradually increases its permanent Red Sea flotilla.

Through the reduction of security cooperation and freezing of military aid, Washington (unsuccessfully) seeks to pressure Cairo to roll back relations with its great power rivals. However, the U.S. avoids a major break in ties due to their strategic importance. Rising Russian and Chinese influence in Egypt pushes Israel to maintain limited coordination with both on key national security issues such as Gaza and the Red Sea.

Economic distress as a result of low oil prices leads to public unrest and violent repression of opposition voices throughout the region, especially in Algeria, Egypt, and Iraq. Already poor state services decline further due to budget cuts and growing populations. Cairo is also facing intensifying water scarcity, and then, as a result, a food shortage ensues in Egypt and causes the price of basic foodstuffs to rise in nearby countries. Radical Islamic terror groups abound throughout the region, taking advantage of protracted conflicts in Libya, Yemen, Syria, and Iraq. Lebanon devolves into a renewed civil war, which is exacerbated by external interference. Hezbollah is momentarily distracted from Israel but retains its missile capabilities as a deterrent.

The Shi‘a minority in the Gulf states are incited by Iranian propaganda directed at them, and Yemen’s Houthis conduct frequent strikes targeting Gulf states’ infrastructure with advanced missiles and UAVs. Despite Iran’s provocative activities in the conventional realm, it puts its nuclear ambitions on hold temporarily to avoid unintentionally inviting an airstrike by the U.S. or Israel.

The U.S. refrains from directly confronting Iran out of concern that it will be drawn into another decades-long quagmire. The Gulf monarchies’ increasing repression of their minority and dissident populations remains a major point of contention between Washington and its Arab allies.

Over the course of the decade, between 2020 and 2030, the U.S. places sporadic but severe pressure on Israel to respond affirmatively to new peace proposals regarding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, requiring Jerusalem to make considerable concessions. Washington’s peace efforts are meant to improve its relations (and Israel’s) with the Arab and Muslim world but do not amount to much due to the evasive maneuvers of both the Israeli and Palestinian governments. Israel and Hamas are engaged in frequent violent and intensive clashes that fail to result in any sort of strategic change that would prevent the next round of fighting. Israel reoccupies Gaza in one of those incidents and then withdraws after a year as part of a negotiated agreement that allows the PA to manage Gaza — only to see Hamas retake control of the enclave after several months.

The U.S. bipartisan consensus regarding Israel continues to erode, as hardline Democrats and Republicans grow disillusioned with traditional alliances. Israel is “asked” by Washington to cut its commercial and security ties with China and Russia, and the partial nature of its acquiescence creates a great deal of friction in the U.S.-Israel relationship, exacts economic costs vis-à-vis China, and complicates Israel’s ongoing air campaign in Syria.

The residual U.S. forces in Iraq, Syria, and the Gulf are meant to blunt Iranian, Chinese, and Russian influence. Iraq and Syria remain theaters of low intensity conflict between Israel and the U.S. on one side and Iran-backed forces on the other; these confrontations are characterized by recurring crises and increasing lethality.

This scenario depicts how making great power competition the primary prism of the U.S. policy in the region could destabilize its traditional alliances and put it in a position of disadvantage in that very competition. It also shows how the erosion of the U.S.-Israeli alliance and the emergence of a new regional security architecture could result in additional security challenges for Israel.

“Making great power competition the primary prism of the U.S. policy in the region could destabilize its traditional alliances and put it in a position of disadvantage in that very competition.”

Scenario #3: Mexican Standoffs

The speedy global economic recovery from the COVID-19 crisis is exploited by the U.S. to increase pressure on China and reduce commitments in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. Energy prices recover to pre-COVID levels, but the consensus among experts remains that a major long-term decline in demand is expected over the coming decade due to groundbreaking advances in renewables.

American forces withdraw from Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan, and their presence in the Gulf is reduced. These steps are facilitated by a popular revolt in Iran that deposed the Islamic Republic and replaced it with a secular nationalist government. However, it soon becomes apparent that the new government retains the ancien régime’s hegemonic ambitions.

The Iranian-Arab faultline in the region revives Arab nationalism and efforts to increase economic, political, and military cooperation between Arab states. The Saudis and Egyptians consolidate a bloc of anti-Iranian countries. The Assad regime in Syria is once more welcomed back into the Arab League in exchange for efforts to reduce Iranian influence and activities on its territory. Iran then expands its cooperation with Kurdish separatists in Iraq and Syria to increase its leverage, and Turkey tries to divert water from the Aras river, leaving Iran facing water scarcity in its eastern provinces.36

Moscow seizes the changes in Tehran as an opportunity to realize its aim of establishing a natural gas cartel among the world’s top four suppliers: Russia, Iran, Qatar, and Turkmenistan. This leads to growing tensions between Russia and Turkey and rising American support for Ankara as a counterweight to Russian influence in the Middle East. Furthermore, China is hostile toward the new cartel, which imposes additional costs on its energy imports and seeks to limit its influence in Central Asia. China increases its support for Egypt as a means to reduce Russian influence in the country and in Africa more broadly.

The many points of contention between the great powers hinder their ability to prevent regional conflicts from erupting. A war breaks out as Egypt, Sudan, and Eritrea fight against Ethiopia and South Sudan over access to water supplies. After several months of fierce clashes a reconciliation process is initiated under the auspices of the African Union, Russia, and China. The U.S. and the EU are not involved in the process.

In the second half of the decade, sporadic violence by Shi‘a militias in Iraq spills over into the Gulf, resulting in attacks on critical infrastructure including oil pumping stations, refineries, and pipelines. However, the glut in production and the decline in demand mean that prices do not shoot up and remain at or around 2019 levels.

In 2027, Egypt conducts a nuclear test in its eastern desert. Cairo declares that it is the first Arab country to attain a nuclear weapons capability, and it has done so due to a growing need for self-reliance in deterring Iranian aggression and ensuring continued access to vital water supplies in light of tensions with Sudan and Ethiopia over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. It appears as though the bomb was developed within the framework of a covert project funded by Riyadh. The great powers’ overtures to pressure Cairo to forfeit its nuclear weapon fail after Iran acquires a nuclear weapon in 2028 (apparently purchased from North Korea) and in 2029 when “special security arrangements” between Pakistan and Turkey are declared — widely interpreted as Islamabad extending its nuclear umbrella to Ankara.

In this scenario, reduced U.S. pressure on Iran does not eliminate the possibility of regime change, but the new regime may not enter the Western orbit or forfeit hegemonic and nuclear ambitions if doing so has not or cannot deliver considerable improvements in Iranians’ living conditions. At the same time, the next country in the Middle East to acquire nuclear weapons is not necessarily Iran, and several nuclear powers might appear in parallel/cascade over a short period of time. Growing Turkish and Iranian ambitions might revive Arab nationalism as a unifying political cause or idea in the region. With the drawdown of U.S. influence and presence, the Middle East could become an arena for strategic competition between Russia and China.

Scenario #4: Free-for-all

The global economic crisis drags on long after the COVID-19 health crisis abates, and so energy prices remain depressed and the economies of the Middle East are hard hit, including the wealthy Gulf states. This leads to a decline in the interest of great powers in the region. However, the U.S. and Europe continue to focus on the global importance of human rights and democracy, pressuring Arab regimes throughout the region to comply with them and threatening sanctions if they do not.

The Middle Eastern regimes’ incompetent handling of the COVID-19 crisis along with worsening structural economic problems leads to a growing sense of frustration among the populations. Radical Islamic groups are viewed by growing numbers of the general public as attractive anti-regime alternatives.

The rise of the sea level combined with an earthquake in the Mediterranean in 2025 generates a tsunami that hits the city of Alexandria hard,37 killing thousands and leaving 1 million homeless. The widespread public criticism of the regime caused the military to announce President al-Sisi’s resignation, beginning a long period of political unrest throughout the country.

In the second half of the decade, Israel capitalizes on the relative weakness of Egypt and the Gulf states in order to expand cooperation with them. There is a significant rise in demand from these Arab states for joint ventures with Israel on technology related to desalination and agriculture — and this helps them to cope with climate change more successfully than many other states in the region that refuse cooperation with Israel.

Extreme drought in Iran leads to a wave of protests that forces the regime to take especially harsh measures to crush dissent. This timing, in addition to the social and economic crises ripping through Lebanon, is identified by Israel as an opportunity to take military action to degrade Hezbollah’s military capabilities and the Iranian nuclear project. Israel destroys Iranian nuclear sites in Natanz, Isfahan, and Fordow. Tehran responds with a symbolic missile attack on Israeli soil, and a “Three-Day War” between Israel and Hezbollah ensues. Israel strikes thousands of Hezbollah targets in Lebanon, but suffers significant damage to its own infrastructure from precision missile strikes. Iran sets out to rebuild its nuclear program in heavily fortified underground sites and quickly reinforces Hezbollah capabilities, including the provision of additional stockpiles of precision weapons.

After stabilizing the situation in Tehran and putting an end to the domestic unrest, the Government of Iran undertakes a policy of increasing support for the militias in Iraq (in the context of an ongoing civil war in the divided country) and launching covert campaigns to destabilize the Gulf monarchies.

Economic distress in Jordan results in the overthrow of the Hashemite ruler by Islamist forces, which then leads to increased tensions with Israel and ultimately the abolition of the 1994 peace agreement. Infiltrations from Jordan oblige Israel to build an extensive fence to protect its eastern border.

Radical Islamic terror, which rears its head in the West Bank following the war with Hezbollah and regime change in Jordan, compels Israel to re-occupy that territory and dismantle the PA. Ironically, it is with Hamas in Gaza that Israel is able to reach an interim agreement that includes investments in and development of Gaza supported by the Qatar-Turkey axis. Continued low energy prices have made the project of shipping gas from Israel to Europe no longer economically viable, and the Israeli government decides to use the gas for internal consumption and to sell it to Gaza.

This scenario demonstrates that a “great power vacuum” and resulting deterioration of the regional order could be accompanied by opportunities for Israel to diminish significant military threats at a lower cost. However, without political maneuvers to consolidate those gains, they could prove to be short-lived and take on considerable risk for a multi-front crisis. It also highlights the formidable threats that climate change might pose to regional regimes as early as the next decade.

“Regime change in the Islamic Republic of Iran does not guarantee that Tehran’s regional or nuclear ambitions will be curbed. Any benefits yielded from the fall of the regime could prove to be ephemeral without considerable engagement by the West.”

IV. Key Takeaways for Israeli Decisionmakers

The variables of U.S. involvement in the Middle East and the region’s economic situation provided the basic outline for mapping out scenarios, though developments in all four cases were non-linear rather than the straightforward and uneventful continuation of existing trends. For those who might contend that some aspects of the futures sketched out seem unlikely or unrealistic, we acknowledge that they may not appear probable, but given the developments of 2020 we felt entitled — if not obligated — to abide by Herman Kahn’s advice to “think the unthinkable.”

The thought experiment that is the basis for this article highlights the significant possibility that Israel’s strategic environment will change in dynamic ways:

- Changes in the dynamics of great power competition in the Middle East might bring about significant changes in the structure of regional camps, which will not necessarily prove helpful for advancing Israel’s core national security interests. From the American perspective, putting too much emphasis on great power competition could backfire on its other important regional assets. In addition, it is worth considering the possibility that frictions between Moscow and Beijing will result from Russian and Chinese ambitions in the region.

- The “Abraham Accords” do not constitute an irreversible change in the dynamics between Israel and Arab countries or entirely disconnect these relations from the Palestinian issue. As much as it is an opportunity for both sides, the latent divergences between Israel and the Arab states demand that diplomatic relations should be never taken for granted.

- Regime change in the Islamic Republic of Iran does not guarantee that Tehran’s regional or nuclear ambitions will be curbed. Any benefits yielded from the fall of the regime could prove to be ephemeral without considerable engagement by the West.

- The acquisition of nuclear weapons by other Middle Eastern countries might not be initiated by Iran, could occur suddenly, and may involve several new actors almost in parallel. The first priority on the Israeli national security agenda is to prevent nuclearization by any Middle Eastern country.

- Deterioration of the regional economy/order might bring opportunities to diminish major military threats to Israel at reduced costs or increase its regional footprint through deeper intra-regional cooperation.

- The ongoing erosion of bipartisan support for Israel in Washington, potentially exacerbated by political polarization in the U.S. or a variety of other factors such as difficulty in managing great power competition, may lead Washington to depart from its longstanding and fairly steady support.

- Climate change could have significant implications for the future dynamics of the region, in terms of the fallout from worsening phenomena like water scarcity as well as cooperative relations developed in order to mitigate such problems.

Following this exercise, the next stage in researching the future of Israel’s strategic balance could include examining how Israel’s possible domestic trajectories could impact its view of these scenarios as well as its ability to advance its interests in light of them. Although we did not consider scenarios of Israel’s internal development, and instead focused mainly on its external environment, the former may ultimately prove to be the most decisive variable for its future. In addition, it might be worthwhile to broaden the horizons of this research by considering the impact of possible counter-trends to some of the key trends mentioned above, for example the reversal of the shift toward multipolarity and a return to a more unipolar world.

Serious preparation for the future demands that Israel remain flexible and attentive to anticipate possible inflection points, devise options to cope with their consequences, and mitigate the risks of high-impact scenarios even if it is difficult to determine their likelihood. Continued thinking about the future may also allow Israel to identify potential opportunities earlier and to take the necessary steps to seize them, thereby increasing the likelihood that they can be realized. How Israel fares in this realm will depend on investment in formalized long-term planning mechanisms, vesting them with authority, and ensuring that the decisionmakers at various levels allocate a significant portion of their time to planning for a range of potential alternative futures.

Endnotes

1. World Economic Forum. “The Global Risks Report 2020.” January 15, 2020. https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-risks-report-2020.

2. Merriam-Webster. “Forecast” definition. Accessed February 19, 2021. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/forecast.

3. Peter Bishop, Andy Hines, and Terry Collins. “The current state of scenario development: An overview of techniques.” Foresight 9 (1). February 2007. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228623754_The_current_state_of….

4. Alun Rhydderch. “Scenario Building: The 2x2 Matrix Technique.” June 2017. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331564544_Scenario_Building_Th….

5. “Overview of Methodologies.” OECD. Accessed February 19, 2021. https://www.oecd.org/site/schoolingfortomorrowknowledgebase/futuresthin….

6. MIT Sloan Management Review defines a weak signal as follows: “A seemingly random or disconnected piece of information that at first appears to be background noise but can be recognized as part of a significant pattern by viewing it through a different frame or connecting it with other pieces of information.” From Paul J.H. Schoemaker and George S. Day. “How to Make Sense of Weak Signals.” MIT Sloan Management Review. April 1, 2009. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/how-to-make-sense-of-weak-signals/.

7. Charles Roxburg. “The use and abuse of scenarios.” McKinsey & Company. November 1, 2009. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-fina….

8. Andrew Curry and Wendy Schultz. “Road Less Traveled: Different Methods, Different Futures.” Journal of Future Studies. May 2009. https://jfsdigital.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/134-AE03.pdf.

9. Rafael Ramirez, Malobi Mukherjee, et al. “Scenarios as a scholarly methodology to produce ‘interesting research.’” Science Direct. 2015. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0016328715000841.

10. Jonas Svava Iversen. “Futures Thinking Methodologies — Options Relevant For ‘Schooling For Tomorrow.’” OECD. http://www.oecd.org/education/ceri/35393902.pdf

11. Hannah Kosow and Robert Gassner. “Methods of Future and Scenario Analysis: Overview, Assessment, and Selection Criteria.” German Development Institute. 2008. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258510126_Methods_of_Future_an….

12. “Mapping the Global Future.” National Intelligence Council. December 2004. https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/Global%20Trends_Mapping%20the%20Glo….

13. Also found in similar projects such as: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/ME2020.pdf.

14. “Mapping the Global Future,” p.20: Davos World provides an illustration of how robust economic growth, led by China and India, over the next 15 years could reshape the globalization process — giving it a more non-Western face and transforming the political playing field as well.

15. “Mapping the Global Future,” p. 42.

16. Leo Blanken. “COVID-19, Information, and the Deep Structure of the International System.” The Cipher Brief. July 20, 2020. https://www.thecipherbrief.com/column_article/covid-19-information-and-….

17. Brun Itai. “Intelligence Analysis: Understanding Reality in an Era of Dramatic Changes.” (In Hebrew) https://www.intelligence-research.org.il/userfiles/banners/Itai.Brun.pdf.

18. Brun Itai, “Intelligence Analysis: Understanding Reality in an Era of Dramatic Changes.”

19. Oded Eran. “Middle East Economies: Dim Light at the End of the Tunnel.” Institute for National Security Studies. November 10, 2020. https://www.inss.org.il/publication/middle-east-economy/.

20. Peter Bishop, Andy Hines, and Terry Collins. “The current state of scenario development: an overview of techniques.” Foresight 9 (1). February 27, 2007. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/14636680710727516/f…

21. Padraíg Murphy. “The Rules-Based Multilateral Order: A Rethink Is Needed.” The Institute of International and European Affairs. March 2, 2020. https://www.wita.org/atp-research/the-rules-based-multilateral-order-a-….

22. Michael Singh. “U.S. Policy in the Middle East Amid Great Power Competition.” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. March 30, 2020. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/us-policy-middle-ea….

23. Eric Brewer. “Toward a More Proliferated World?” CSIS. September 2, 2020. https://www.csis.org/analysis/toward-more-proliferated-world.

24. Paul Rivlin. “Middle East Demographics of 2030.” The Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies. August 21, 2019. https://dayan.org/content/middle-east-demographics-2030.

25. “MENA Generation 2030.” Unicef. August 2019. https://www.unicef.org/mena/sites/unicef.org.mena/files/2019-08/MENA%20….

26. “Middle East And North Africa Human Capital Plan.” Human Capital Project. October 2019. http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/907071571420642349/HCP-MiddleEast-Plan-….

27. Huseyin Emre Ceyhun. “Social Capital in the Middle East and North Africa.” Arab Barometer. November 2019. https://www.arabbarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/social-capital-public-….

28. “Fragility in the World 2020.” Fragile States Index. The Fund for Peace. Accessed February 18, 2021. https://fragilestatesindex.org.

29. Sagatom Saha. “How climate change could exacerbate conflict in the Middle East.” The Atlantic Council. May 14, 2019. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/how-climate-change-cou….

30. Water Scarcity Clock. Accessed February 18, 2021. https://www.worldwater.io.

31. Shira Efron. “Rising Temperatures, Rising Risks: Climate Change and Israel’s National Security.” The Institute for National Security Studies. January 4, 2021. https://www.inss.org.il/publication/climate-change-and-national-securit….

32. Robert A. Manning. “Emerging technologies: New challenges to global stability.” The Atlantic Council. Jul 7, 2020. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/e….

33. Jonas Svava Iversen. “Futures Thinking Methodologies – Options Relevant For “Schooling For Tomorrow”. OECD. http://www.oecd.org/education/ceri/35393902.pdf.

34. Joseph S. Nye Jr. “Peering into the Future.” Foreign Affairs. July 1994. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/1994-07-01/peering-future.

35. David N. Bengston et al. “Strengthening Environmental Foresight: Potential Contributions of Futures Research.” Ecology and Society. 2012. https://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol17/iss2/art10/.

36. Connor Dilleen. “Turkey’s dam-building program could generate fresh conflict in the Middle East.” ASPI. November 5, 2019. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/turkeys-dam-building-program-could-ge…

37. “Rising Sea Levels Threaten Egypt’s Alexandria.” VOA News. September 7, 2019. https://learningenglish.voanews.com/a/rising-sea-levels-threaten-egypt-….

About the Authors

Ari Heistein is a Research Fellow and Chief of Staff to the Director at the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS). His research focuses on U.S. foreign policy, the U.S.-Israel relationship, Israeli strategy vis-à-vis Iran, and the Yemeni civil war. He received his BA in Middle Eastern Studies from Princeton University and his MA from Tel Aviv University. His writings have been published in a variety of international media outlets, including The Atlantic, Foreign Policy, Jewish Review of Books, and War on the Rocks.

Lt. Col. (ret.) Daniel Rakov is a research fellow at the INSS. Previously, he had a 21-year career in the IDF, mainly in the Israeli Defense Intelligence (Aman). During this period, he was employed primarily in research and analysis missions, and dealt with the most important strategic and operational challenges in front of the IDF and the Israeli government, in almost every geographical area of interest to the State of Israel. Daniel holds a Master’s of Business Administration (MBA) and a BA (magna cum laude) in Middle Eastern history, both from Tel Aviv University.

Dr. Yoel Guzansky is a Senior Research Fellow at the INSS, specializing in Gulf politics and security. Dr. Guzansky is also a Non-Resident Scholar at the Middle East Institute and was previously a Visiting Fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, an Israel Institute Postdoctoral Fellow, and a Fulbright Scholar. He served on Israel’s National Security Council in the Prime Minister’s Office, coordinating the work on Iran and the Gulf under four National Security Advisers and three Prime Ministers. He is currently a consultant to several ministries.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.