Iraq’s Oct. 10 election may be more consequential than its immediate results suggest. Some of the subtle facts and dynamics surrounding the election point to interesting trends and possibilities, more so than the headline-grabbing expansion of Muqtada al-Sadr’s power in the Iraqi legislature, or the losses suffered by candidates representing Iran-backed militias.

It may seem paradoxical at first, but this election could provide the conditions for a future rebound in voter engagement. The record low turnout, which Iraq’s Independent High Electoral Commission (IHEC) put at 43% of registered voters (equivalent to 38% of eligible voters), confirms earlier polling data that pointed to the erosion of confidence in Iraq’s electoral process since 2018 due to the influence of powerful parties and militias. Understandably, the shortcomings of that election, combined with relentless violence against political activists, motivated some parties and candidates representing the Tishreen protest movement and its allies to opt out of the October election, and pushed many voters, particularly young people, to stay home.

However, this parliamentary election was clearly different from the previous one in 2018. International support and Iraqi efforts have produced a “technically sound” election that is considered an improvement over 2018 and has so far been free of the widespread irregularities, suspected foul play, and cover-up allegations that tainted that election.

The technical side of the October vote, though improved, was not flawless. Indeed, there have been some embarrassing data glitches in the days since Oct. 10 — in one case an IHEC publication mistakenly doubled the number of voters at more than 50 million. Setting those aside, the absence of credible allegations of widespread fraud may go a long way toward restoring confidence, at least with regard to election day management and fraud prevention, provided there’s ongoing strong oversight and engagement by Iraqi civil society and the international community.

Pre-election fraud and manipulation remain the biggest challenge to establishing a fully credible electoral process that Iraqis can wholeheartedly embrace. Many of Iraq’s major parties, including Sadr’s bloc, his rivals in the Fatah coalition, and the major Kurdish parties, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), for that matter, would not be eligible to compete in elections if IHEC were to follow the law. Iraqi laws prohibit political parties from having military or paramilitary organizations — a legal obstacle that has not prevented armed groups, including those under U.S. sanctions for terrorism, from fielding candidates and winning seats.

Like the fighting that broke out in Kirkuk after the 2018 election results upset certain parties, the sabre rattling by Iran-backed militias now underscores the fact that the credibility of Iraqi democracy depends not on short-term stability achieved through muhasasa, the ethno-sectarian power-sharing system that has come to define Iraqi politics since 2003, but on rule of law and keeping weapons out of politics.

Given their coercive power, attempting to ban any of these violators from competing in elections would be dangerous. But drawing clear lines between the political and the military — slowly and carefully — so that all parties can fairly compete in elections is a demand that Iraqi reformists and the international community should be more vocal about.

While the threats of violence coming from Fatah members and others who lost seats are alarming, the tension will most likely be resolved through compromises on what’s at stake for them. Traditionally, this has been ministerial appointments and access to exploitable public funds, such as the annual $2.3 billion allocated to the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) — a budget line item that many Iraqis, from ordinary people to prime ministers, suspect is being used to pad the pockets of militia commanders.

Despite Sadr’s party winning 74 seats in the 329-seat legislature, twice as many as the next party, Baghdad is likely heading toward another government formation process dictated by the usual rules of power-sharing: that all parties powerful enough to cause trouble may win a seat at the table and a share of government positions commensurate with its weight in parliament. Despite headlines to the contrary, there are no kingmakers in Iraqi politics.

For example, Sadr’s gain vis-à-vis Fatah is somewhat offset by the gains achieved by Fatah’s ally, Nouri al-Maliki. The former prime minister’s State of Law bloc has seen its seats increase from 25 to 37 and is working to build a coalition to compete with Sadr for the designation of “largest bloc.” As negotiations proceed, the extreme options that are the rivals’ first choices for prime minister will likely be excluded in favor of less contentious “compromise candidates.” Some will be rejected for being too Sadrist, others for being too friendly to Washington, too close to Iran, or for being Nouri al-Maliki, with all the baggage that entails.

The immediate post-election shock and euphoria for Fatah and Sadr, respectively, created a fog that may soon begin to lift. Triumphant remarks about a purely Sadrist prime minister, and counter threats by the militia rivals will give way to compromises. After all, from Ibrahim al-Jafari’s 2005 premiership to that of Adil Abdul-Mahdi in 2018, Sadr steadily accumulated power from being part of the government while still able to attack it when it suits his purposes. Sadr may begrudgingly recognize that a Sadrist prime minister may not be a good thing. Against the backdrop of Iraq’s ongoing economic crisis, failing to deliver better services and living conditions when the prime minister is a Sadrist would be much harder to defend or spin than if the premier was from another party, or a weak compromise candidate. As for Fatah’s factions, going to war promises no economic returns and jeopardizes the interests of their allies in Tehran. Ultimately, the Fatah factions will have to accept a slightly reduced status in the next government and settle for a share of positions proportionate to their seats, and perhaps guarantees for some of the PMF budget.

But while the next government may continue “business as usual,” the seeds for change will have a chance to extend roots. Another notable fact about the election, and one that may be effective in combating voter apathy in four years, is that Tishreen representatives performed relatively well despite the calls for boycott. The Tishreen-inspired Imtidad Movement’s success in winning nine seats is remarkable for two reasons. First, unlike the traditional parties, Imtidad couldn’t promise jobs and money to supporters, or use religious or ethnic sentiments for mobilization. Second, it was young voters, the constituency that would have likely voted for parties like Imtidad, that led the calls for boycotting the election.

What does this mean for Tishreen? Of the possible scenarios evaluated in pre-election research, Tishreen can be expected to continue to challenge the status quo despite failing to capture the levers of power. Indeed, Imtidad leaders say they’re planning to challenge the muhasasa establishment by staying out of the next government and forming an opposition bloc — a new precedent in Iraqi politics. Since 2003, political actors have always sought to be part of the government to share the spoils in the name of balance and consensus among Iraq’s communities.

Moreover, it is interesting to see important actors within Tishreen that boycotted the election, like al-Bayt al-Watani, join forces with those who participated. Reflecting a high level of coordination and deliberate planning, al-Bayt al-Watani and Imtidad are working to renew Tishreen’s momentum through political opposition within parliament and popular pressure on the streets.

This post-election consolidation of Tishreen could help unlock more of Tishreen’s potential in four years. Popular vote numbers highlighted three interesting points to consider. First, they suggest that districting and sound electoral tactics can give savvy parties a great advantage over disorganized opponents. Even though the Sadrists won 400,000 votes fewer than the 1.3 million they received four years ago, they managed to snatch 22% of the seats (74) with just under 900,000 votes (10% of the votes cast). With half as many votes, Fatah captured a mere 16 seats, less than a quarter of Sadr’s. Second, and perhaps more importantly, popular voting figures reveal that Imtidad won almost 300,000 votes, a very respectable figure for a newcomer that didn’t use patronage, fear, or ethnic or sectarian sentiments to persuade voters. Finally, it was candidates running as independents (recognizing that some may have abused the label to disguise their partisan links) who won the most votes, a whopping 1.7 million.

If the cooperation among various Tishreen elements lasts, it could position the movement’s future candidates to realize more of their electoral potential. This election may have set the stage for something big in four years.

That ruling parties like the Sadrists won large shares of seats in Iraq’s latest parliamentary elections is not news. It has happened before, again and again. But the fact that, even with a record low voter turnout, a genuinely homegrown opposition movement has managed to win seats — that is a first, and that is news.

Omar Al-Nidawi is a Middle East analyst focusing on Iraqi political, security, and energy affairs. He is a Program Manager at the Enabling Peace in Iraq Center (EPIC), a Truman national security fellow, and a guest lecturer of Iraqi history and politics at the Foreign Service Institute. The opinions expressed in this piece are his own.

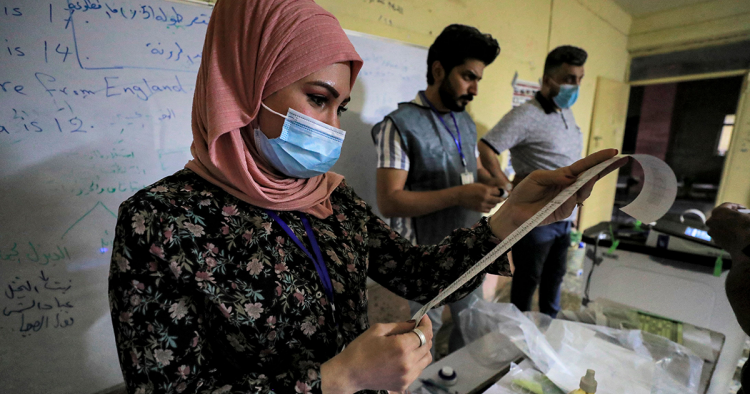

Photo by AHMAD AL-RUBAYE/AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.