This is the first in a series of articles examining and rebutting the shu al-badīl? argument (“What’s the alternative?”) in the run-up to presidential elections next June, when Bashar al-Assad, president of Syria since 2000, is widely expected to seek a fourth seven-year term of office.

***

Political manipulation of cultural heritage is a powerful tool in the armory of soft power. Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad understands this well, as does Russia’s President Vladimir Putin and Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

In Syria the latest initiative on this front came in response to the recent conversion of Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia from a museum to a mosque. The construction was announced, funded by Russia, of a mini-replica Hagia Sophia in the small Orthodox Christian town of Suqaylabīah in Hama Province. The headline looks good, promoting “peaceful dialogue” between faiths, and aims to project Bashar and Putin as multicultural moderates — unlike Erdogan. As Nabeul al-Abdullah, commander of Syria’s National Defense Forces (NDF) militia and originator of this brainchild, explained, “It is designed to show the real face of Syria, where different civilizations and cultures coexist.”

Closer scrutiny however reveals that this Syrian Hagia Sophia will be so mini, at just four meters by four meters, that scarcely a dozen worshippers will fit inside. But its tiny size belies a powerful message beyond the symbolism of its name. It will sit on land donated by al-Abdullah, just a few kilometers from the Turkish observation post at Morek, and is also a way for Russia to openly ally with the local Orthodox Christian community.

Reconstruction funds are in short supply in Syria. Forty-five percent of its housing has been lost in the last nine years of war. Yet while most of that housing, largely belonging to the majority Sunni Muslim population, remains in ruins, money, it seems, can always be found when it’s deemed important enough.

The Assad narrative

It all feeds into the Assad narrative, unflinchingly adhered to since the outset of the Syrian war in March 2011, that only he, Bashar, can be the true defender of the country and its heritage. Shu al-badīl? (“What’s the alternative?”) runs the loyalist mantra. “It’s Assad or the terrorists.” From 2013 onwards the systematic destruction by ISIS of high-profile historic sites across Syria and Iraq, like Palmyra, served to make Assad’s narrative even more plausible — “It’s Assad or the extremists.”

With presidential elections looming next June, this narrative warrants careful scrutiny. Since the start of the war many organizations have been keeping detailed photographic and video records of damage to cultural monuments. Thanks to their efforts, an enormous database has now been assembled proving the extent of the destruction, how reparable it is, and how the damage occurred. The data shows that by far the greatest damage to Syria’s historic monuments can be laid at the door of the regime, just as figures confirm that 90 percent of civilians and 95 percent of medical workers have been killed by the regime. Given the huge disparity in weaponry between the regime and the rebels, this is hardly surprising. Flattening by aerial bombardment can only be laid at the door of Syrian and Russian government jets and helicopters. The Free Syrian Army and all its subsequent iterations never had air power.

Preserving Syria’s cultural heritage

Most of the organizations concerned with Syria’s cultural heritage are of necessity based outside the country but many also have links to Syrians on the ground, such as the Syrian Heritage Archive Project in Berlin, Association for the Protection of Syrian Archaeology (APSA) in Strasbourg, Heritage for Peace, Le patrimoine archéologique syrien en danger, SHIRIN - Syrian Heritage in Danger, The Day After - Heritage Protection Initiative, and the American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) in the U.S. Apolitical websites like Monuments of Syria, compiled by former Australian Ambassador to Syria Ross Burns, are also extremely valuable, feeding vital data for future reconstruction into the relevant UNESCO departments.

When it comes to actual reconstruction on the ground, once again, it is seldom the Assad regime or its Russian or Iranian allies who are taking the lead. True, the Chechen government of Ramzan Kadyrov, not generally noted for philanthropy or piety, is funding the flagship reconstruction of Aleppo’s Umayyad Mosque. But Aleppo’s famous souks are being rebuilt by the Aga Khan Development Network, an apolitical foundation with a genuine concern for cultural heritage. Even before the war it spent millions restoring Old Aleppo. As for hotel restoration in Aleppo, of properties such as Al-Mansouria Palace and Beit Salahieh, that is being funded privately by wealthy Syrian expatriates. Individuals with sufficient funds have restored their own war-damaged homes, without government support.

Efforts on the ground

Most Syrians, young and old, have a deep pride in and awareness of their country’s cultural identity, as is amply demonstrated by the networks of volunteers working on the ground to protect it in any way they can. In Idlib, the northwest province outside regime control, the city museum reopened in 2018 after five years of closure, with ongoing work funded from abroad to document and record its priceless cuneiform tablets from the Bronze Age site of Ebla. The valuable contribution of many of these volunteer groups has long been recognized by UNESCO. As well as providing vital documentation, they also work together to safeguard archaeological sites from illegal excavations and help track down looted antiquities.

Within Syria the Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums (DGAM) is state-run, with all that implies for limited funds. While some of its employees left the country as refugees, other well-qualified and committed individuals remain, doing their best in difficult circumstances. Some have even lost their lives for their passion, like high-profile Palmyra archaeologist Khaled al-As’ad.

Others, especially in rebel-held areas like Idlib, work incognito for their own safety, and are almost entirely unrecognized, yet they have meticulously documented damage to the province’s 732 sites. Together these account for over a third of Syria’s antiquities, including the Dead Cities and their 2,000 early churches, which were designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2011. These committed individuals continue to work, even today during the ongoing fighting. Were the regime to fall after free and fair elections next June, many of those currently in exile would return to their beloved country like a shot, bringing expertise and foreign funding with them, together with the highest standards of restoration.

“The reality” — or Assad’s version of it

A quick glance at the Culture & Arts section of the state-run Syrian Arab News Agency (SANA) website shows how the regime frequently posts short items that collectively imply it is somehow protecting these sites. It shows pictures of organized trips to Palmyra with loyal supporters, “to preserve the Syrian heritage.” The website also talks of documenting “the reality.” Since the start of the war in 2011 a special side column has run under the header “Reality of Events” — Assad’s version of reality.

On May 5, 2015 Putin held a “victory concert” in Palmyra, flying in a special orchestra from Moscow, after Russia drove ISIS fighters out. The musicians were bussed at speed across the desert, so that Putin could seize the moment to launch himself by video link from the ancient stage of Palmyra onto the world stage, as “the savior of Syria” and “the defender against terrorism.” He claims that mantle still.

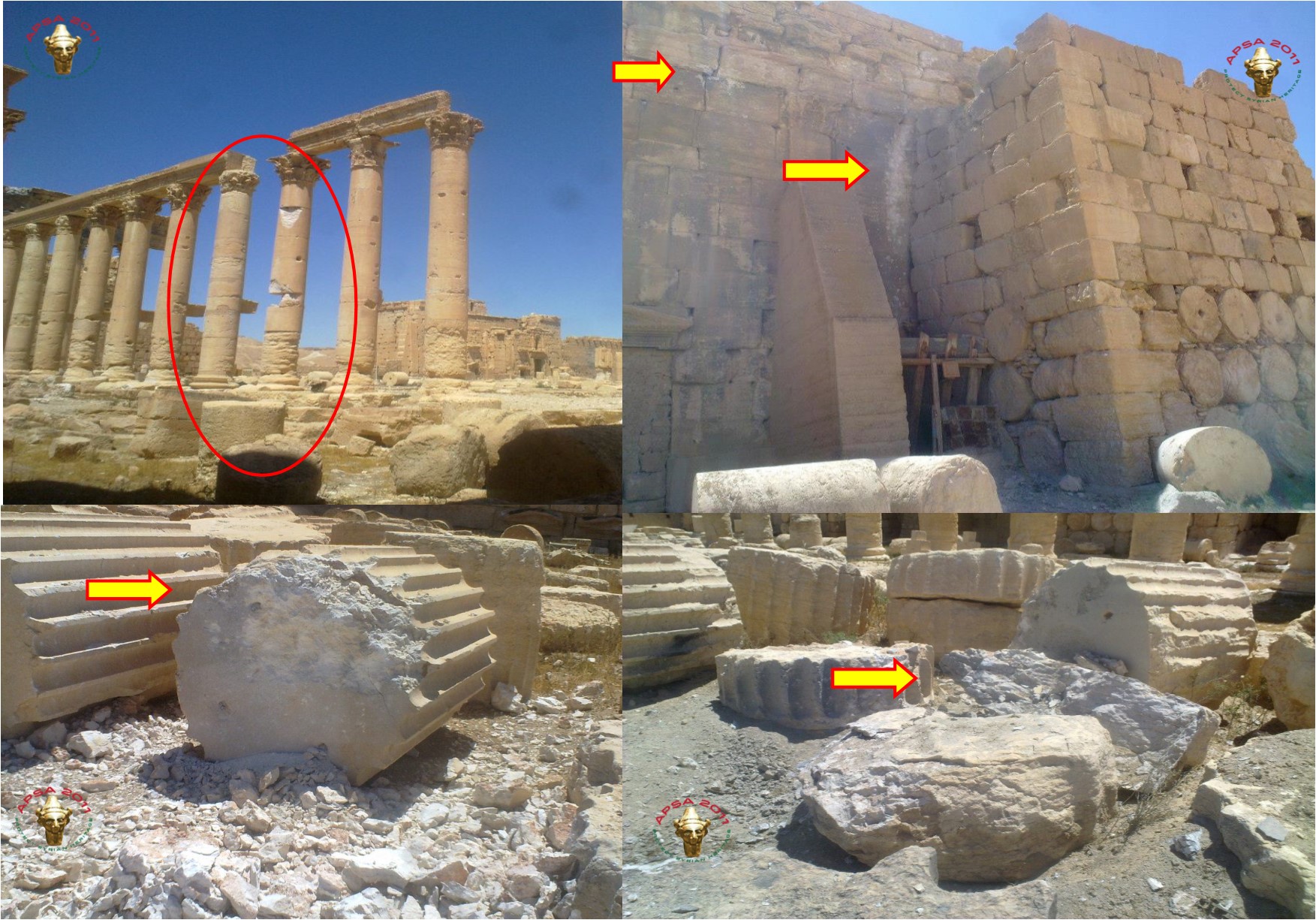

But while ISIS’s seizure of Palmyra in 2015 shocked the world, no one spoke of the damage caused earlier in the war by government forces. Long before ISIS completed the destruction, they badly damaged the site, installing a multiple rocket launcher in Diocletian’s Camp, driving heavy tanks and military vehicles across the archaeological site, and shelling the Temple of Bel, causing several columns to collapse. ISIS’s detonation of the site’s key monuments during the summer of 2015 erased both the evidence and the memory of the earlier abuses by regime soldiers.

At Krak des Chevaliers, the world’s best preserved Crusader castle, the Syrian air force dropped bombs inside the castle, blasting out the intricate carving of the Gothic loggia in front of the refectory, causing the first ever man-inflicted damage to the castle fabric in its 800-year existence. Yet the regime put the blame squarely on “the terrorists.” Later they released photos of their own repair work in progress, always presenting themselves as the ones fixing the problems, never the ones causing them.

In Aleppo the regime narrative is equally misleading. The damage to the Aleppo Umayyad Mosque was portrayed as the work of “the terrorists” even though earlier video footage recorded Free Syrian Army soldiers helping volunteers to dismantle and move precious items like the 13th-century wooden minbar to safety. Local archaeology students built protective bomb blast walls in front of the tiled tomb of Zachariah (father of John the Baptist) and encased the medieval sundial in the courtyard within protective breeze blocks, then padlocked shut the lid.

After the regime retook control of Aleppo, Assad held his own “victory” concert on National Day — April 17, 2018 — in the modern amphitheater of the Citadel, thinly disguised as a celebration of the country’s independence, with patriotic singing, dancing, and parading. It was live-streamed on national TV as loyalist crowds waved their Syrian flags on cue to camera.

Assad has skillfully cast Syria’s rich multicultural heritage as a reflection of himself, appropriating everything that's positive about Syria’s cultural identity as if he were somehow responsible for creating it — a deeply insidious way of incrementally airbrushing your opponents out of the picture.

“Building back better”

The ongoing global pandemic has triggered new ways of thinking, and shown how people can do more for less, through clever use of digital technology. Economic and social benefits can spring from well-managed cultural heritage projects, bringing employment to young and old alike. The V&A’s Culture in Crisis workshops, for example, are actively exploring alternative opportunities for future collaboration and cooperation between heritage experts abroad and local communities on the ground, aimed at “building back better.” Involvement of local people in online training and heritage education can all be conducted virtually.

Such initiatives would never be undertaken or supported by the current Syrian government, where coordination between ministries and other authorities is weak or largely absent, and where civil society initiatives are seen as challenging to state authority, closed down, or met with arrest and imprisonment.

Yet Syria’s unique cultural identity remains. It was always there, way before the Assads — and is still there, in spite of the Assads.

Diana Darke is a non-resident scholar with MEI's Syria Program and an independent Middle East cultural expert and Syria specialist. She is the author of My House in Damascus: An Inside View of the Syrian Crisis (2016), The Merchant of Syria (2018), and Stealing from the Saracens: How Islamic Architecture Shaped Europe (2020). The views expressed in this piece are her own.

Main photo courtesy of the author.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.