On Jan. 5, shortly after Qassem Soleimani, former commander of Iran’s Quds Force and its second most influential official after Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, was assassinated in Iraq by an American drone strike, Tehran announced that it would no longer remain committed to the enrichment restrictions laid out under the 2015 nuclear deal — officially known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA).

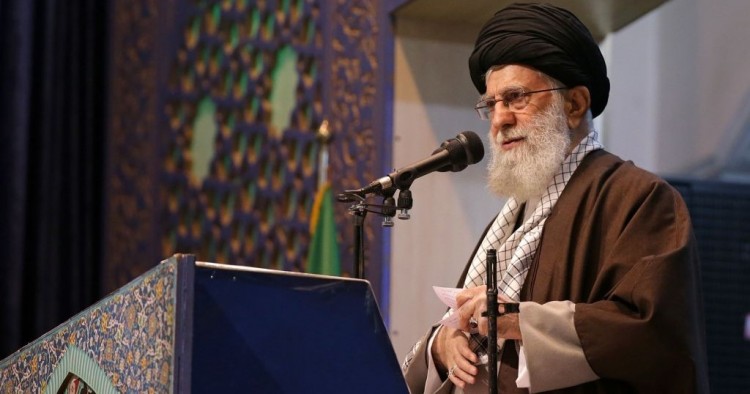

“Iran will continue its nuclear enrichment with no restrictions ... and based on its technical needs,” a government statement cited by state TV read. And then came Ayatollah Khamenei’s pledge to exact “severe revenge” for the Soleimani killing as the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) struck two Iraqi bases housing U.S. troops with over a dozen missiles in retaliation on Jan. 8.

European signatories to the JCPOA — Britain, France, and Germany (or the E3) — have since triggered the accord’s “dispute resolution mechanism” (DRM) in response to Tehran’s retaliatory noncompliance, a process that could culminate in the reopening of its nuclear dossier in the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) and the “snapback” of all UNSC sanctions that have been lifted under the JCPOA.

Honor-bound and fear-bound

Even though European diplomats have rushed to assuage Iranian concerns about the possible resumption of international sanctions, Tehran perceives this as an extension of the U.S. “maximum pressure” campaign and is very unlikely to back down or substantially change its defiant behavior — domestically promoted as a counterpolicy of “maximum resistance” — even if punitive UNSC resolutions against it are reinstated.

Around two years into its costly resistance against unprecedented external pressure and after so many lives have already been lost in Iran, Iraq, and Syria, the Iranian leadership now feels honor-bound to keep up as any substantive compromise, conciliation, or change of direction could compound its credibility crisis and further alienate its core support base at a time when the Islamic Republic needs it most. Unlike in 2013, during the marathon of nuclear negotiations that resulted in the 2015 accord, there is now barely any room politically for another round of “heroic flexibility.” That would probably be Khamenei’s undoing as an ideological-political leader among his supporters, who would demand to know why his ultimate “surrender” did not come before all that hefty cost, in blood and treasure, was inflicted on the nation.

But the Iranian leadership is also fear-bound to keep up, for any substantive compromise will likely be interpreted by its nemeses as proof of the success of the “maximum pressure” campaign and invite more, perhaps greater, demands, or so the solidifying threat perceptions in Tehran suggest. Veteran revolutionaries themselves, the leaders of the Islamic Republic have been deeply wary of reiterating the “follies” of the pre-1979 Pahlavi regime, whose overthrow was expedited by the shah’s notorious failure to exercise effective leadership, resolve, and authority against the revolutionaries.

Softness in the face of growing pressure will thus not only entail enormous normative costs for the ruling system, but could also embolden its external opponents to build up pressure in the hope of extracting greater concessions, if not total surrender.

Tehran’s consequent path dependency and persistence with costly “resistance” is in fact a structural feature of Iran-West hostility at the moment and will not be undone overnight, and particularly not under duress.

A day after the E3 activated the DRM on Jan. 14, The Washington Post reported in an exclusive scoop that the Trump administration had threatened to levy a 25 percent tariff on European automobiles exported to the United States if Britain, France, and Germany refused to initiate the critical process.

While the European signatories to the JCPOA have scrambled to fight off the impression that it was the U.S. threat that coerced them to trigger the deal’s DRM and make it clear that they had made the decision “weeks ago” in response to “Iran’s escalatory behavior and violations” — as an American official noted — UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s explicit emphasis on the need for replacing the Obama-era nuclear agreement with a “Trump deal” points to a harsher reality. Following the U.S. assassination of Soleimani, it seems the European powers have basically lost faith in the utility of efforts to salvage the JCPOA and therefore decided to go along with the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” campaign against Tehran sooner and at a relatively lower strategic cost now rather than later and at a much higher cost in the future. In other words, the reckless elimination of Soleimani appears to have awakened Europeans to the bitter truth that they lack enough power and resolve to stand up against American unilateralism and that Trump will ultimately have his way, with or without European opposition.

“I’ve had very direct discussions — as well as Secretary Pompeo has — with our counterparts,” U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin told CNBC on Jan. 15. “I think you saw the E3 did put out the statement and have activated the dispute resolution. And we look forward to working with them quickly and would expect that the UN sanctions will snap back into place.”

This will, however, help the Islamic Republic to frame and therefore discredit possible reinstitution of UNSC sanctions as an extension of “American” hostility toward Iran rather than a broad-based “international” campaign against its nuclear ambitions, a feat the Obama administration had managed to achieve in the pre-JCPOA era.

Moreover, and equally importantly, the Iranian leadership now feels buoyed by an effective “test run” of an unprecedented methodology of suppression at home — involving, for the first time, a near-total internet shutdown and systematic use of live fire — on the one hand, and a strategically sobering missile offensive against bases housing American forces in Iraq on the other. There is almost no evidence to suggest that they will not resort to a similar course of action if the occasion arises.

It is, therefore, not surprising that both moderates and hardliners have almost unanimously inveighed against the EU, with President Hassan Rouhani going as far as to warn that European troops in the region could be “in danger” much like their American peers, and Foreign Minister Javad Zarif broaching the possibility of Iran quitting the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) if UNSC sanctions snap back against it.

While intense diplomatic efforts are underway to break this escalatory cycle of hostility and confrontation, Tehran will likely press ahead with its defiant behavior unless and until the Trump administration provides it with an “off ramp,” as any major deviation under current circumstances could cost the Islamic Republic dearly in terms of credibility, authority, and eventually survival. To put it in a nutshell, the U.S. “maximum pressure” campaign” has arguably locked Iran into a posture of “maximum resistance” from which it is structurally implausible, if not impossible, to break free as long as the former remains in place.

Maysam Behravesh is a senior political analyst at Persis Media and a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science at Lund University, Sweden. The views expressed in this article are his own.

Photo by Iranian Supreme Leader Press Office/Handout/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.