Contents:

- Four factors to watch to assess the Saudi-Iranian diplomatic opening

- Where is Biden’s anger at Saudi Arabia?

- On the anniversary of Syria’s civil war, justice and accountability remain elusive

- Something has to give: Tunisia’s political and economic situation is unsustainable

- Pakistan’s politics grow more confusing and alarming

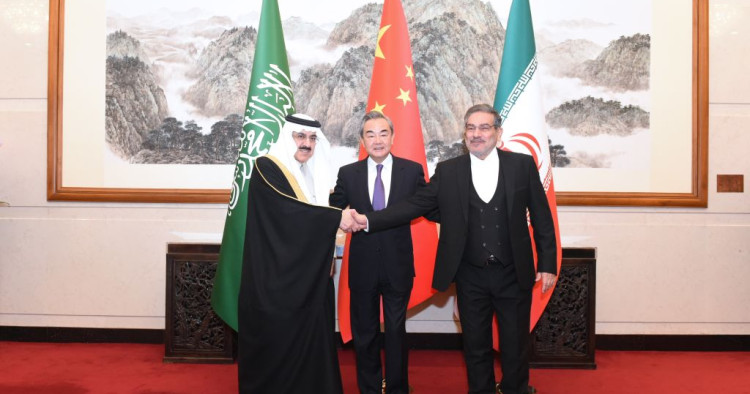

Four factors to watch to assess the Saudi-Iranian diplomatic opening

Brian Katulis

Vice President of Policy

-

The fact that China played such a visible role in finalizing and announcing the Saudi-Iranian agreement to resume diplomatic ties is the most notable thing so far about the deal.

-

The relative importance of this diplomatic opening will depend on whether it leads to decreased Iranian destabilizing actions, produces a new diplomatic channel on Iran’s nuclear program, allows Beijing to build on its role in the region, and creates fresh incentives for Israel to resolve its conflict with the Palestinians.

The surprise Iranian-Saudi agreement brokered by China could help advance broader stability in the region if the parties live up to the general commitments expressed in the reporting on the deal. Iran and Saudi Arabia announced in Beijing on Friday that they will re-open embassies after a seven-year cutoff of ties, work to revive a security pact, and resume bilateral trade, investment, and cultural accords. The fact that China played such a visible role in finalizing and announcing this agreement is the most notable thing so far about the deal.

The general agreement comes after years of efforts to bridge divides between the two countries. Iran and Saudi Arabia had met at least half a dozen times directly and in regional forums over the past three years as part of multiple lines of effort to reduce regional tensions.

As we wait to see how things develop, four aspects in particular are worth watching:

1. Will this lead to a reduction of Iran’s attacks against Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states? Iran has conducted a series of attacks using missiles, drones, and cyberattacks against key sites in the kingdom and the neighboring United Arab Emirates over the past five years. In addition, Iran has sponsored several terrorist plots in the Gulf. A main test of this agreement is, thus, whether it produces progress toward stabilizing the region.

2. Will this create a new diplomatic channel to address Iran’s nuclear program? Like many other regional and outside powers, Saudi Arabia is deeply concerned about Iran’s nuclear program. For years, the main forum for engaging Iran in diplomatic efforts has been the P5+1 talks (involving the United States, United Kingdom, Russia, China, and France, along with Germany), which did not fully integrate the concerns of key countries in the Middle East. President Joe Biden’s plan A, of rejoining the Iran nuclear deal, hasn’t worked out yet, so the Beijing-brokered Saudi-Iranian talks may offer some limited hope for a new avenue. If these bilateral negotiations are to be meaningful and impactful, however, they will have to tackle regional concerns about Iran’s nuclear program — otherwise, the opening will be just optics.

3. Will China build on this diplomatic engagement to expand its role in the region? China is dependent on the Gulf region’s energy resources for its economic rise, much more so than America or Europe. It has sought to reduce tensions between Iran and Saudi Arabia before. The U.S. increasingly recognizes regions like the Middle East as arenas of strategic competition with other great powers, which isn’t exclusively limited to the military sphere — it involves economic, technological, and diplomatic moves too. The fact that China visibly brokered this agreement is an important sign of its increased engagement in the region and Beijing’s desire to see a de-escalation of tensions. More and more, when America pulls back diplomatically from a part of the world, China stands ready to fill the gap left behind by U.S. disengagement.

4. What does it mean for possible Israeli-Saudi ties? Israel’s new government led by Benjamin Netanyahu initially responded negatively to the deal, in line with its more assertive posture toward Iran compared to that of the previous Israeli government. Time and again over the past few months, Netanyahu and his ministers have hinted that additional kinetic actions against Iran’s nuclear program might be necessary. Last January, the U.S. and Israel conducted their biggest bilateral military exercise to date, in large part to send such a signal to Iran.

The diplomatic opening mediated by Chinese could produce a tactical and operational gap between Israel and Saudi Arabia on how to proceed with Iran and its nuclear program, potentially limiting Israel’s military and kinetic options; or it could result in a new diplomatic approach since neither the Saudis nor the Israelis want to see Iran getting a nuclear weapon or persist with its destabilizing regional actions and support for terrorism. The actual outcome will depend on how deep this new opening between Tehran and Riyadh is.

Still, a broader opening between Israel and Saudi Arabia seems unlikely anytime soon without progress on the Palestinian front. Despite quiet investment and economic efforts — building on years of behind-the-scenes intelligence and counterterrorism cooperation — Saudi Arabia needs to see some progress on Palestine before opening ties with Israel, and that seems impossible with the present Israeli government and its posture toward the Palestinians.

The Abraham Accords are to Benjamin Netanyahu what the 2015 Iran nuclear deal was to Barack Obama: both leaders saw these as key diplomatic accomplishments. Netanyahu wants nothing more than to see a broader normalization that includes Saudi Arabia. That means Saudi Arabia has a great deal of potential diplomatic leverage with Israel on the Palestinian front should Riyadh choose to use it.

Follow on Twitter: @Katulis

Where is Biden’s anger at Saudi Arabia?

Firas Maksad

Director of Strategic Outreach, Senior Fellow

-

The Beijing-brokered understanding between Saudi Arabia and Iran sits better with Democrats than Republicans.

-

Saudi Arabia’s openness to Chinese diplomatic overtures was shaped by growing American reluctance, over multiple administrations, to uphold long-held security commitments to its Arab Gulf partners.

Pundits and policymakers anticipated a backlash from the White House late last week, as news broke of an unexpected Chinese-brokered understanding between archrivals Saudi Arabia and Iran. The deal, reportedly, will allow for Riyadh and Tehran to re-establish diplomatic relations and could contribute to the potential de-escalation of simmering conflicts throughout the Middle East. To many American eyes, in the era of great power competition, Saudi Arabia appeared to grant China a major diplomatic victory in a region traditionally seen as within the United States’ sphere of influence.

However, the expected negative response from Washington has not materialized. Instead, the Biden administration cautiously welcomed the deal as potentially contributing to regional stability and to a peace agreement in Yemen. On the other hand, prominent Republicans like Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-N.C.) and others, with whom Saudi Arabia has enjoyed a warmer relationship, are rebuking the kingdom, reminding Riyadh that it remains firmly tethered to the U.S. for its security.

What accounts for the Democrat-Republican role reversal, especially after Saudi Arabia was long accused of being too closely associated with former President Donald Trump, Jared Kushner, and leading Republican foreign policy hawks?

Riyadh has repeatedly insisted its policies are driven by Saudi national interests, not domestic politicking in the U.S. This was especially the case last October, when Saudi Arabia bucked pressure from the White House not to cut oil production ahead of the midterm elections. Regardless, Washington is predisposed to view the world through a partisan lens. And in that sense, the Chinese-brokered understanding with Iran notches Saudi Arabia closer to Democratic views and objectives in the Middle East rather than those of Republicans.

Democrats cannot champion an end to war in Yemen and de-escalating conflicts in the region, many of which feed on the Saudi-Iranian rivalry, and criticize an agreement that ostensibly aims to achieve exactly that. In 2016, President Barack Obama shocked the Saudis and America’s other Arab partners by asking them to learn how to “share the region with Iran.” Managing Saudi differences with Iran is the basic premise behind the announced Saudi-Iranian understanding.

But perhaps it is the afforded recognition of a more pronounced Chinese role in the Middle East that should be the cause of concern? Here too, Saudi Arabia’s policies did not develop in a vacuum but grew out of persistent American reluctance, both Democratic and Republican, to uphold long-held security commitments to Arab Gulf partners. Most notably, President Trump chose not to support a kinetic response when Iran attacked Saudi oil facilities in 2019, and the Biden administration was largely absent when Iranian drones struck targets in the United Arab Emirates in January 2022.

So, if the U.S. is incapable or unwilling to deter such Iranian attacks, and American led-diplomacy has failed to stop Iran from achieving near weapons-grade uranium enrichment, then is it not understandable for Saudi Arabia to seek Beijing’s assistance? China maintains considerable leverage over Iran. It also shares Washington’s vested interest in maintaining regional stability and the free flow of hydrocarbons since about half its imports are from the Middle East.

Whether China can ultimately deliver where America has not will become clearer in the next two months. Both Saudi Arabia and Iran are expected to work toward de-escalation and the reopening of their respective embassies. A meeting of foreign ministers is slated to take place beforehand. And the scope and durability of the Chinese-brokered détente will become more evident.

But what Friday’s landmark announcement telegraphs is the urgent need for the U.S. to determine and clearly communicate its strategic posture in the Middle East. Does Washington want to recommit to the region and maintain its unrivaled position in a part of the world still vital to the global economy — and to China’s growing energy needs? Or does it want to engage in burden-sharing and allow Beijing a greater diplomatic and perhaps, one day, security role?

It may be too early to tell, but judging from the Biden’s administration’s muted initial reaction, Riyadh appears to have made the right bet.

Follow on Twitter: @FirasMaksad

On the anniversary of Syria’s civil war, justice and accountability remain elusive

Charles Lister

Senior Fellow, Director of Syria and Countering Terrorism & Extremism programs

-

Though hostilities in Syria are at a low point, the sources and drivers of instability are more deeply engrained and severe than ever before, while humanitarian suffering has never been greater.

-

Assad remains the principal cause and obstacle to any solution to Syria’s refugee and displacement crisis, to the humanitarian and economic collapse, and to the persistent activities of terrorist groups and geopolitical conflict on Syrian soil.

Syria’s crisis will enter its 13th year later this week, and while military hostilities are at a low point, the sources and drivers of instability are more deeply engrained and severe than ever before. Violence associated with terrorism, insurgency, ethnic and geopolitical hostilities, as well as organized crime remain rife and intractable in every corner of Syria. The level of humanitarian suffering, meanwhile, has never been higher, with more than 90% of Syrians living under the poverty line and dependence on aid nearly as high.

The devastation caused by the earthquake on Feb. 6. turned public attention back to Syria. The destruction and nature of the international community’s response also served to underline a number of long-held but forgotten realities — principally, that the regime remains a brutal and predatory actor interested only in its own survival. That Bashar al-Assad has sought to exploit the earthquake to enhance his international position is far from surprising, but the West’s apparent indifference to the resulting normalization moves has been damning.

The death of more than 500,000 Syrians and the displacement of more than half the population was not somehow undone by a natural disaster — and certainly not by one that struck opposition areas worse than anywhere else in Syria. More than 100,000 Syrians remain unjustly detained, disappeared, or missing by regime action. Thousands are dead and wounded as the result of more than 340 confirmed regime chemical weapons attacks, and roughly half of Syria’s basic infrastructure is destroyed or heavily damaged because of Assad’s scorched earth campaign. These are all cold, hard, and well-known facts. Yet the memory of all those lost, and the basic human expectation for justice and accountability, is being trodden under the feet of regional governments that have taken to sickeningly calling Assad their “brother.”

To those seeking to normalize Assad and his regime, Syria’s best chance of stability ostensibly lies under the rule of a man against whom the world has more evidence of war crimes and crimes against humanity than was brought to bear against Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Party at the Nuremberg Trials. Moreover, Assad stands today at the top of a narco-state producing drugs with a greater street value than all of Mexico’s cartels combined. The idea that Assad is the key to stability is absurd. In truth, Assad is the principal cause and obstacle to any solution to Syria’s refugee and displacement crisis, to the humanitarian and economic collapse, and to the persistent activities of terrorist groups and geopolitical conflict on Syrian soil.

On the upcoming anniversary of Syria’s brave and hopeful uprising, the world would do well to remind itself of what kind of “leadership” Bashar al-Assad has displayed since 2011.

Follow on Twitter: @Charles_Lister

Something has to give: Tunisia’s political and economic situation is unsustainable

Intissar Fakir

Senior Fellow and Director of Program on North Africa and the Sahel

-

As President Kais Saied grows more isolated and paranoid, the chances for regime change are increasing.

-

As Tunisia’s economic struggles continue, the president is using the uncontested powers he has acquired to entrench his autocratic populist rule, ramping up arrests and targeting imagined critics and foes.

President Kais Saied is flailing. The worse the economic environment in Tunisia gets, the more he seems intent on ignoring that and stirring up public sentiment against imagined foes. And as Saied grows more isolated and paranoid, the chances for regime change are increasing. Whether this leads to another popular uprising or a negotiated transition remains unclear, but the current situation is unsustainable.

Economically, the country continues to struggle and inflation remains high, increasing to 10.4% as of February. The International Monetary Fund loan that could provide some much-needed relief for state budgets and help restore a modicum of international trust in the economy has been postponed, putting it in limbo once again.

At the same time, the president continues to use the uncontested powers he has acquired to entrench his autocratic populist rule. The country’s new parliament lacks legitimacy, elected on turnout of just 11.2% of eligible voters, and based on a controversial constitution adopted with voter turnout of 30%. Saied also disbanded the municipal councils elected in 2018 to vest more power in local bodies and further the country’s plans for decentralization. Arrests have ramped up and include political figures, civil society activists, businesspeople, and judges, all of whom have captured his imagination or that of his interior ministry as critics or threats.

Adopting yet another hateful populist trope, Saied has blamed sub-Saharan migrants for a supposed rise in crime. This is encouraging local anger to be channeled toward migrants as a misplaced culprit. Saied’s paranoia is not limited to migrants though; the president has for months complained that he is being targeted by assassination plots, exhibiting a remarkable degree of fear and isolation. Not only has the president dashed any hopes about his ability to correct course, but he has become the country’s main problem. And even as Tunisians are exhausted, protests are increasing. Tunisia is growing more isolated on the regional and international stages, and the country’s options are becoming more and more limited.

Follow on Twitter: @IntissarFakir

Pakistan’s politics grow more confusing and alarming

Marvin G. Weinbaum

Director, Afghanistan and Pakistan Studies

-

It is unclear if provincial elections in Punjab and Kyber Pakhtunkhwa will occur on time, but opposition PTI party leader Imran Khan sees victories there as an important step in reclaiming national power, while the government hopes to postpone and is using the legal system against Khan.

-

A further delay of elections is likely to generate massive PTI demonstrations, necessitating the deployment of more security forces and further raising the prospects of a military intervention.

Pakistan’s political scene is normally confusing and chaotic. Its politicians often engage in unbridled behavior in their contest for power, and its politics can take the most erratic turns. But recently, the country’s political landscape has become especially bizarre and worrisome.

Attention is currently centered on whether the elections in Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa provinces, planned for April 30, thanks to presidential and judicial intervention, will in fact occur on time. Opposition Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party leader Imran Khan sees victories for the two provincial assemblies as an important step in his campaign to reclaim national power taken from him a year ago. With strong showings, Khan hopes to capitalize on his present popularity; a recent opinion poll finds him with nearly double the public support of the sitting prime minister, Shehbaz Sharif. The ruling coalition, headed by the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N), wants to cling to power as long as possible by postponing elections. Pakistan’s Election Commission conveniently claims that it lacks the financial resources necessary to hold upcoming provincial contests, and the country’s civilian and military intelligence services warn that present security conditions dictate against holding elections in the coming months. In hopes of undermining and splitting the opposition, the Sharif government has also employed the legal system, which has opposition leader Khan dodging arrest in several cases lodged against him for alleged criminal actions.

The main characters in Pakistan’s sometimes byzantine political drama, Khan and the governing coalition’s leadership, particularly the PML-N’s Maryam Nawaz, are striving to take control of the narrative and reveal the others’ moral blind spots. Pakistan’s political fate is intertwined with this ongoing bitter rivalry between a vengeful Khan and a badly wounded political establishment, where neither wants to be seen as a villain and both relate a story of injustice to prove their innocence. This was clearly visible last Wednesday, when a PTI worker died mysteriously following a clash between party protestors and Punjab police. His death has ignited a new round of finger-pointing, with PTI leadership blaming the government-backed interim Punjab administration for the murder. In turn, the interim government holds Khan responsible for spreading false propaganda and casting hatred against the state institutions.

Pakistan’s politics could become still more disruptive over the coming months. A further delay of elections is likely to generate massive PTI demonstrations, necessitating the deployment of more security forces. The chances of serious violence erupting are especially great if Khan is arrested and barred from contesting for public office. Meanwhile, former prime minister Nawaz Sharif, convicted of corruption and on the lam from justice in London, may strike a deal for his return and proceed to mobilize government sympathizers to confront the opposition. Political deadlock and turmoil amidst the authorities’ efforts to keep Pakistan’s economy afloat and fend off rising domestic terrorism naturally raise the possibility that the military, together with the judiciary, may at some point decide to intervene and, applying the infamous doctrine of necessity, set aside Pakistan’s latest exercise in democracy.

Research assistant Naad-e-Ali Sulehria contributed to this piece.

Follow on Twitter: @mgweinbaum

Photo by Luo Xiaoguang/Xinhua via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.