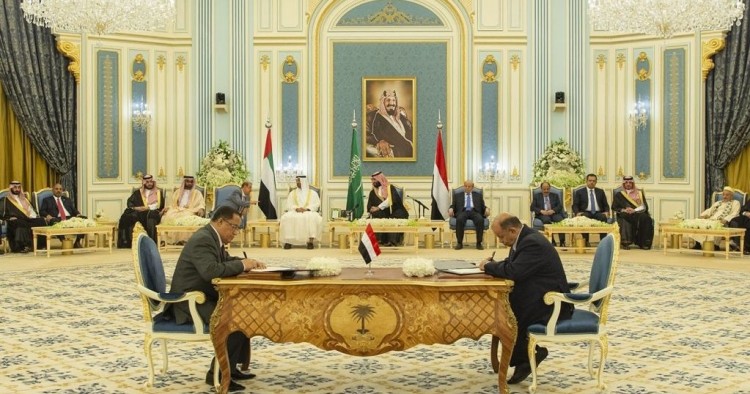

Following the violent confrontations between Hadi government troops and southern forces partisan to the Southern Transitional Council (STC) in August 2019, Saudi Arabia worked hard to fix the ruptures in the anti-Houthi coalition. At the beginning of November 2019, after two months of negotiations, the Saudi efforts led to the signing of the Riyadh Agreement. The agreement’s ambitious timeline ran for three months with deadlines set at 15, 30, 60, or 90 days. By January 2020 as most of the deadlines had already passed without implementation, Saudi Arabia made another attempt to implement the provisions of the deal, introducing what was known as the “matrix” with a 15-day deadline in mid-January 2020.

What was implemented and what wasn’t?

In January 2020, most of the deadlines expired without being implemented, except for the return of the prime minister to Aden, facilitated by the STC, and military withdrawals of southern troops, as stipulated in the Riyadh Agreement and the matrix. The STC made further concessions by allowing more ministers to come to Aden, even though it was not part of the Riyadh Agreement, providing access to military sites, and allowing inspection of heavy weaponry. It released all detainees from the government side who were arrested in August. The government, however, complied with neither the Riyadh Agreement, nor the matrix. The government did not appoint a new cabinet after 30 days that was supposed to consist of 50 percent politicians from the South. Likewise, it did not appoint a new governor and security chief to Aden. The prime minister did not ameliorate the socio-economic situation of the population and did not secure people’s salaries, as called for in the Riyadh Agreement. Instead, due to increasing corruption, food prices rose, the administration remained inefficient, and social services deteriorated.

Moreover, the government did not withdraw its troops from Shabwa and Abyan back to Marib, as mandated in the Riyadh Agreement. Instead, it has tried to replace former presidential guards, who secured the presidential palace in Aden until August 2019, with troops led by Sa‘id Ma’ayli from Marib. In addition, one detainee from the southern side was not yet released, and civilians, as well as local STC personnel in Abyan, Hadramawt, and Shabwa have been arrested by government troops since the signing of the Riyadh Agreement. In January 2020, the Laqmush tribe in Shabwa was encircled by government troops and cut off as a punishment for their pro-STC stance. In mid-February 2020, government troops took Muhsin Masawa, an 80-year-old man, hostage in Shabwa because they could not find their primary target, his son. In addition, the government denied the implementation committee, consisting of a joint delegation of government, STC, and Saudi representatives, access to Shabwa to control troop movements and attacks against civilians.

Reemergence of extremist groups

The security situation has deteriorated since the Riyadh Agreement was signed. Due to the dismantling of the counterterrorism Shabwani Elite Forces in August 2019, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, which was largely expelled from southern governorates since 2016, has reemerged and operates in certain areas now. Leading figures among the southern security forces and STC representatives have been killed. Further incidents have created mistrust between the STC and the government: On Feb. 8, 2020, the government tried to move through Aden a Coastal Forces Brigade led by Zaky ‘Ali Hussein (Abu al-‘Aabid), a former follower of Osama Bin Laden in Afghanistan who has been accused of involvement in the USS Cole bombing in 2000. It was a unilateral move, outside of the scope of the matrix, and the Southern Security Belt Forces stopped the brigade from entering Aden due to the terrorist background of its leader. Saudi Arabia, accompanying the brigade, answered with flash bombs from their fighter jets, enraged about the refusal of the Security Belt Forces to obey the order.

A greater international role?

As all deadlines of the Riyadh Agreement have expired, the implementation committees have stopped their work and implementation is now on hold. The STC, which is advocating for its inclusion in the UN-led peace process, sees the Riyadh Agreement as key to getting a seat at the negotiation table and, therefore, made significant concessions to reach the agreement in November.

While troops from Marib have been extremely involved in Shabwa and Abyan since August 2019, strategically important frontlines, such as Nihm, close to Sanaa and bordering Marib, have been lost to the Houthis since January 2020. Considering the escalation on the ground and the unwillingness of the Hadi government to keep up its part of the Riyadh deal, perhaps a greater international role in the Riyadh Agreement could help to revive the political process.

Anne-Linda Amira Augustin works as a political advisor in the Foreign Representation of the Southern Transitional Council in the European Union. The views expressed in this article are her own.

Photo by BANDAR ALGALOUD/SAUDI KINGDOM COUNCIL/HANDOUT/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.