This article is part of the publication Thinking MENA Futures, produced in conjunction with MEI's Strategic Foresight Initiative and the MEI Futures Forum. Read the other articles in the series here.

The last year and a half has been tough on the world. The COVID-19 pandemic affected all aspects of life. We have done what we can to keep the disease at bay, and respected each other by following hygiene and physical distancing rules. Yet for much of the world’s poor — including the 82.4 million displaced people globally — the lockdowns were catastrophic, plunging millions into poverty, risking eviction and forced into overcrowded shelters. If you are living hand-to-mouth, only able to buy food and pay rent based on what you have earned that day, staying at home is impossible. And for refugees and other forcibly displaced persons fleeing persecution and conflict, keeping safe at home is not even an option. Of these displaced, some 12 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) and over 3 million refugees and asylum seekers, in addition to some 365,000 stateless persons, are living in the Middle East. In addition, next door in Turkey, over 3.6 million refugees from Syria, Iraq, and other nationalities make up the largest refugee population hosted by any one country in the world. They have been dealt the misfortune to be caught up in large-scale conflict, often treated merely as pawns in domestic, regional, and global quests for control.

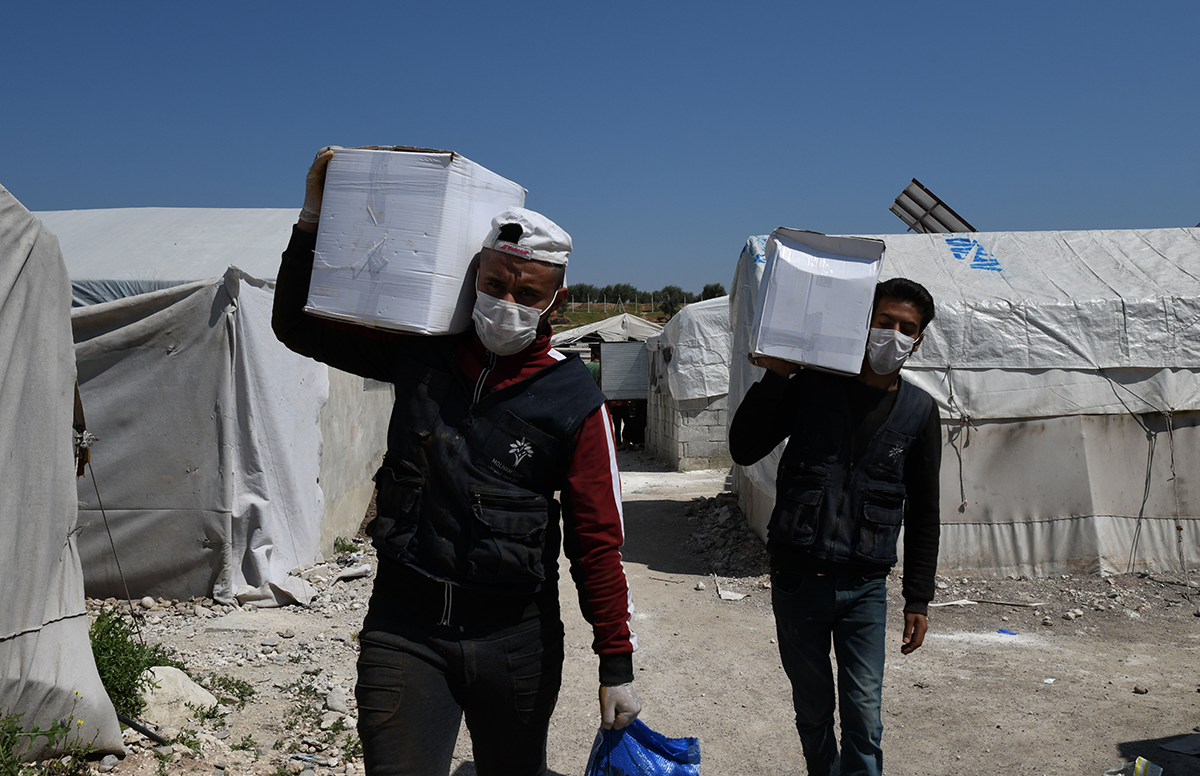

The thousands of staff of UNHCR, the U.N. Refugee Agency, who work in the Middle East see the human consequences every day, of people killed and injured or forced to flee, often leaving behind family, friends, livelihoods, property, and everything familiar.

The situation in Syria remains the world’s single largest displacement crisis, with around 6 million refugees globally and over 6 million people displaced within Syria. After more than 10 years of shifting conflict lines, foreign interventions, and economic collapse, the country remains in ruins. Countless people are left with no choice but to seek shelter in bombed out remnants of buildings, exposed to the elements, living in sometimes medieval conditions — in what was once a middle-income country. Some 13.4 million people are currently in need of humanitarian assistance in Syria, almost half of whom are children. According to the World Food Programme, food prices are now 33 times higher than the pre-war average and around 90% of the population is estimated to live in poverty.

I know there are a lot of politics that need to be solved before donors will move on the large-scale reconstruction of Syria that is desperately needed, but being able to do more inside the country to prevent further humanitarian suffering is critical. Is the installation of doors and windows in a school to keep out the cold a humanitarian or a development intervention? Is the provision of a generator for a hospital that keeps the incubators for premature babies running a humanitarian gesture or a development investment?

Countries near to Syria — Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, and Egypt — have borne the greatest burden. For more than a decade they have taken in and sheltered millions of Syrians at great political, economic, and, in some cases, social cost. The Kingdom of Jordan has been a gracious host of Palestinian, Iraqi, and now Syrian refugees for decades. Turkey, the country hosting the most refugees in the world, continues to allow Syrians to access their social services. Iraq and Egypt should also be commended for their reception of Syrians.

One of the most concerning situations anywhere in the world is that of Lebanon, where one in five people is a refugee. COVID-19 has compounded suffering in a country already in deep crisis. The stoic Lebanese people are suffering, and some unscrupulous politicians have sought to deflect responsibility for their own political failings by blaming others, including refugees. Meanwhile Syrian refugees in Lebanon have fallen into the abyss, with some 90% living in extreme poverty, up from 55% just two years ago.

So what can be done to address the refugee crisis?

First, inclusion of refugees in the host country — until repatriation or another durable solution is found — is critical. This means access to schools, health care, and other social services that are critical to more than mere survival. These services must in turn be appropriately resourced by the international community and international financial institutions (IFIs). Turkish, Jordanian, Iraqi, Lebanese, and Egyptian host community parents should not suddenly see their children’s class size doubling. Rather they should be benefiting from more schools, classrooms, and teachers (and similarly clinics, doctors, and nurses in the health system) to help their own and to accommodate refugee children. They must see a “refugee dividend” through investments that are made in their communities and that are left behind once refugees return home.

This is not new for the region, which has been at the forefront of inclusive ways of responding to displacement. The London Conference of 2016, where global leaders and the humanitarian community came together to pledge support for Syrians and the affected region, helped to lay the foundations for such a response, as well as the affirmation of the Global Compact on Refugees by the U.N. General Assembly in 2018.

Refugee inclusion is, however, doubly urgent in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. We have seen governments do the right thing in terms of including refugees in vaccination campaigns (where vaccines are available). What is equally critical now is to help refugees and their hosts stave off the socio-economic impact of COVID and the resulting pandemic of poverty. As governments, along with donors and IFIs, design relief packages, our appeal is that they include refugees in their calculations and in these social programs.

Second, more must be done in countries of origin to remove the obstacles to return. We know that most refugees around the world want to return home. This is no different in the Middle East. UNHCR regularly conducts refugee intention surveys, which provide us with information to inform our programing. Some 70% of Syrian refugees in the region tell us that they want to return home, just not immediately. So we are working to remove the obstacles that they say are preventing them from going home. For some, the main concerns are accessing the documentation that is essential in proving who they are or that shows ownership of housing, land, and property. Others are unsure as to whether they will face legal or political problems upon return or are simply worried they might be conscripted. For others still, it is safe shelter, schools, and the possibility of a job. In this regard, I appeal to the international community to do more to support these humanitarian endeavors inside Syria so that Syrians can indeed live a dignified life.

"What is needed more than anything is for states and leaders to step up to their responsibilities."

Third, it is clear that some refugees will not and cannot go home. They have particular needs and vulnerabilities that must be addressed through third country solutions. Concretely, this means increasing the number of refugees resettled to safe third countries. I therefore welcome the U.S. administration’s commitment to rebuild and increase America’s resettlement program. Resettlement of the most vulnerable saves lives and changes them for the better.

There are other options that must also be made available to allow for the legal movement of some refugees to a place where they will be safe and have the chance to make the most of their potential. These include scholarships, guest worker visas, or family reunification programs. All of these help the refugees themselves, but also their new host country because refugees also bring skills and a drive and determination to succeed. In this regard, we are working not only with governments, but also universities and the private sector to try to expand the number of places available for refugees.

But third country solutions will only remain possible for what remains a very small number of people, especially in a context like the Syrian refugee crisis. This is why what is needed more than anything is for states and leaders to step up to their responsibilities; to cast aside their narrow political interests; and instead work to make peace. For it is only through a peaceful resolution to conflict that displacement itself will be resolved, allowing millions to return home and to begin to rebuild their lives in safety and dignity.

Filippo Grandi is the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

Photo by Muhammed Said/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.