Iran’s Sixth Five-Year Development Plan (2016-21) identifies the energy sector as a key source of revenue and driver of economic growth.[1] The plan envisages increasing oil output by 2 million barrels per day (bpd) to 4.8 million bpd.[2] Achieving this ambitious target will require substantial foreign investment, technology, and expertise. However, Iran faces formidable challenges in efforts to secure these vital inputs, including complex domestic economic and political roadblocks, intensive competitive pressures, and persistent sanctions uncertainty.

As of May 8, 2018, surmounting those challenges has arguably become even more difficult. US President Donald Trump’s announcement of his intention to “withdraw” from the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) and “reinstate” US sanctions levied against Iran[3] is a decision that, in itself, is unlikely to cause the nuclear deal to collapse immediately. Nevertheless, it has introduced an additional layer of complexity and uncertainty to Iran’s energy trade and investment relations.

This article first looks at the nature and sources of Iran’s chronic petroleum predicament. It briefly examines the progress and limitations of Iran’s post-JCPOA energy rebound, discusses the role that Iran’s major Asian energy partners played during and since the 2011-14 sanctions period, and considers whether they are likely to serve as Iran's energy lifeline.

A Chronic Petroleum Predicament

Iran — ranked second in the world in natural gas reserves and fourth in proven oil reserves[4] — has enormous undeveloped hydrocarbons resources with a low cost base. Although the Iranian economy is diversified, the petroleum sector remains of central importance to the country’s wellbeing. Oil still accounts for roughly 80% of Iran’s exports and 30% of the government budget, and is essential in fueling Iran’s industrial development and electricity production.[5] In addition, many of Iran’s products derive from the oil sector (e.g., plastic and rubber products).[6]

However, the Iranian oil industry has languished for years. Crude oil production peaked at 6 mb/d in 1974[7] but has not returned to that level. Domestic political upheaval, coupled with the devastating effects of war with Iraq (1980-88), inflicted critical blows to the oil industry. Over the past two decades, the industry has been beset by production and consumption challenges, as well as the ill effects of international sanctions.

Iran has been experiencing steep production declines in mature fields. More than 70% of Iran’s oil production comes from aging fields with high rates of natural depletion that require major investments to revive.[8] Meanwhile, Iran has had to contend with growing domestic primary energy consumption, energy inefficiencies, and a high degree of energy price subsidization. Oil Minister Bijan Zanganeh has described his ministry as “buckling under the pressure of subsidies” — substantial sums that could otherwise be invested in the energy sector.[9]

These mounting domestic pressures have been exacerbated by international sanctions. The nuclear-related sanctions imposed in late 2011 and mid-2012 reduced Iran’s oil exports by more than one million barrels per day at a cumulative cost exceeding $100bn over the ensuing three years.[10] Between 2011 and 2014, Iranian oil exports plummeted; moreover, Iran was unable to access the hard currency it was paid for its oil. The effectiveness of sanctions, and by extension their adverse impact on Iran, was enhanced by the rapid growth of US oil production from shale. By 2014 US oil output had risen by more than Iran’s entire, pre-sanctions exports.[11]

Iran’s difficulty acquiring badly needed external financial resources and technology has stemmed not just from sanctions but also from the country’s complex and constraining policy environment. The Iranian Constitution prohibits ownership of natural resources by foreign or private entities.[12] Political opposition to letting foreigners invest in Iran’s natural resources remains strong. Even though technocrats can be found throughout the energy sector and state economy, mistrust of foreign governments and companies runs deep.[13] Battles continue to be waged between proponents of strict adherence to revolutionary principles and pragmatists.[14] But far from merely exposing long-standing ideological rifts, these battles reflect struggles over the distribution of the country’s wealth and political power. The need to implement economic and legal reforms so as to attract foreign investment exists in tension with the need to accommodate the demands of powerful domestic stakeholders.[15]

Governance of the Iranian oil sector is marked by “complexity and contestation.”[16] Political actors have intruded into the domain of the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC), limiting its ability “... to pursue aims befitting a commercially driven company in full command of the development of nationalized natural resources.”[17] Upon assuming the presidency, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who had campaigned on a populist platform of eradicating the “oil mafia” and distributing oil wealth, fell into the familiar pattern of purging hundreds of senior management and empowering supporters.[18] The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), in particular, succeeded in gaining a foothold in the oil industry.[19] In the absence of competition from abroad, IRGC-affiliated entities substantially benefited from sanctions. The IRGC’s economic — and political — position thereby markedly improved.

In attempting to reform the economy, including the energy sector, President Hassan Rouhani has encountered stiff resistance from hard-liners in the Majles and from the Revolutionary Guard.[20] The politicization of the oil industry was evident in the struggle over the final design of Iran’s Integrated Petroleum Contract (IPC),[21] which replaced the Buyback Contract (BBC) model that had long been in effect.[22] Iranian construction, engineering, equipment and contracting companies expressed fear that the new model would adversely affect their contracts and sales.[23] The official introduction of the IPC was repeatedly delayed, and finally approved by the Majles only in late 2016.[24] In January 2018, Supreme Leader ‘Ali Khamenei reportedly told the IRGC to divest from those parts of its business conglomerate that are “irrelevant” to the Guard’s core purpose. However, it is not clear how these instructions were interpreted, whether they included the Guard's holdings in the energy sector, and if so, what progress has been made in executing them.

Scope and Limits of the Post-Sanctions Rebound

The coming into force of the JCPOA in January 2016 was accompanied by the easing of energy sector-related sanctions. This development prompted Iran to ramp up crude oil production. Between December 2016 and January 2018, Iranian production increased by 37%, while exports of crude oil and condensate rose by 46%.[25] Rather more quickly than many had expected, Iran regained its position as one of the world’s largest oil exporters.

However, the initial surge in production and exports was due solely to existing production capacity and to exporting volumes that had been stored in terminals and tankers. Furthermore, having reentered global markets at an inopportune time — amidst depressed export volumes and lower prices — Iran missed its revenue targets by a wide margin in spite of its early gains in output and exports. OPEC’s Saudi-led efforts to flood the market and thereby chase shale producers out of business drove prices downward, reducing Iran’s oil revenues.[26]

Iran’s production and its share of OPEC output are now both back around pre-sanctions levels. The NIOC exported record-high volumes of crude oil and condensate (i.e., an average of 2.877 mb/d) in April 2018 — no small achievement.[27] Yet, recent sizable increases in shipments made available for export were primarily due to draw downs of oil stored in tankers at sea and oil freed up by refinery maintenance, rather than a spike in output.[28]

The implementation of the JCPOA encouraged several international oil companies (IOCs) to explore the potential for cooperation.[29] However, their initial enthusiasm has been tempered primarily by uncertainty regarding the possible reimposition of sanctions.[30] As of April 2018, Iran succeeded in signing only two contracts with foreign energy firms to recover and increase its oil and gas production capacity. The first contract was the deal reached with France’s Total and the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) for phase two development of the South Pars gas field[31] — a project that will take time to implement and thus not generate in the short term the billions of dollars in hard currency revenue that the Iranian state needs or expects.[32] The second was signed with the Russian company Zarubezhneft for the re-development of the Aban and Paydare Qarb oil fields, which are both located in western Iran and jointly owned by Iran and Iraq.[33]

An Attenuated Asia Energy Lifeline

The International Energy Agency (IEA) projects that by 2040 Asian countries will import two out of every three barrels of crude oil traded internationally.[34] Iran looks to Asia both as a major market for its oil and as a key source of investment in energy. However, an intense battle for oil market share in Asia and continued sanctions uncertainty have hampered Iran’s ability to capitalize.

Prior to the introduction of stringent US and EU financial and energy sanctions in 2012, China, India, Japan, and Korea were the top destinations for Iranian oil exports.[35] Although all four countries succumbed to pressure by significantly scaling back their imports, albeit reluctantly,[36] none of them completely cut off supplies from Iran. At the height of US sanctions, when Iran was blocked from accessing foreign exchange, some of its major Asian oil customers, notably China, settled the trade balance in goods rather than hard currency,[37] while India partially paid in rupees for some of its Iranian oil.[38] Finally, it should be noted that whereas China scrupulously adhered to UN sanctions and managed to avoid a showdown with Washington, it nonetheless deftly exploited sanctions loopholes and never acceded to American pressure to “isolate” Iran. While Iranian officials might well have come to regard the conduct of some Chinese companies as exploitative,[39] they could not have failed to acknowledge China as being the central strand of the country’s Asia energy lifeline.

Within a year of the relaxation of sanctions, Iran’s oil sales to its Asian customers returned to their pre-sanctions levels.[40] Since then, Asian buyers have taken the bulk of Iran’s oil exports. In 2017, 62% of Iranian shipments of crude oil and condensate went to buyers in Asia.[41] However, this figure is deceiving. That same year, Iran lost its oil market share in Asia to Saudi Arabia, the United States and Russia.[42] Whereas prior to the imposition of sanctions, the developed Asian markets of Japan and South Korea, together, had bought around half a million barrels a day of Iranian crude, the combined crude oil shipments to these countries now run at about half that level. Iran accounts for just a 6% share of Japan’s total crude imports (as compared to Saudi Arabia’s 40%).[43]

In an effort to claw back market share, Iran has offered discounts on freight charges and crude oil prices, as well as spot cargoes (ranging from light to heavy grades), to its term buyers in Asia. In March, the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) reportedly offered to raise the freight discount for India in return for New Delhi agreeing to boost imports,[44] and later lowered further its April prices for light crude oil for its Asian buyers.[45]

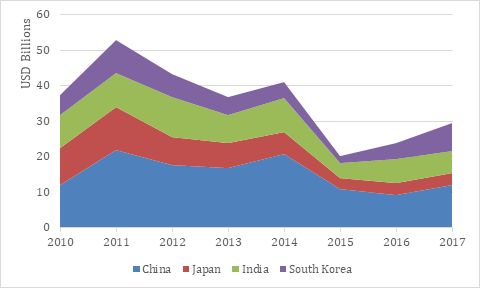

Thus far, the results of Iran’s efforts to reclaim market share in Asia have been decidedly mixed. In the case of China, which alone accounts for about a third of Iran’s crude oil exports, purchases in March 2018 surged.[46] In contrast, India’s oil imports from Iran, which had fallen by 15.7% during the 2017/18 fiscal year,[47] have yet to bounce back. Though there are some signs that the incentives offered to Indian buyers by Tehran might bear fruit,[48] Iran faces stiff competition from Iraq[49] and Saudi Arabia.[50] As Figure 1 below illustrates, Iran has managed to reverse the sharp decline in revenue generated by oil exports to its major Asian customers in the post-JCPOA period. However, given increased gains in output and export volumes, earnings growth has not been as robust as might have been expected due to intensely competitive, low-price market conditions and Asian buyers’ supply diversification efforts.

Figure 1. Iran’s Oil Revenues - Major Asian Buyers

Source: UN Comtrade International Statistics.

Iran has had to contend not just with intensifying competition for the Asian oil market but also with continued sanctions pressure. Iran’s efforts to attract foreign investment and technology from Asian partners have been hampered by the possible “snapback” of sanctions (if Iran is perceived as violating the nuclear deal), the extraterritorial application of US laws, and the possible levying of new sanctions.

Drifting Towards Extended Sanctions Uncertainty

By the time of the May 8 Trump announcement, the uncertainty surrounding sanctions had already taken its toll on Iran. Public statements and threats by President Donald Trump and other senior American officials had had a chilling effect on new investment from Asia, as from elsewhere, even though the US administration had stopped short of abandoning the nuclear deal.[51] Thus, to some extent, the Trump administration had succeeded in thwarting Iranian efforts to unleash the full potential of the oil and gas sectors merely by threatening to walk away from the nuclear deal, rather than by actually doing so.

However, now that the Trump administration has decided to act on its threat to withdraw from the nuclear agreement, Iran’s oil and banking sectors are likely to be the initial targets of sanctions, jeopardizing the country’s fragile economic recovery. To be sure, Iran has played this game before — and would likely apply all of its past experience and capacity do so again.[52] For Iran, the critical factor in determining whether, and how well it can withstand a new round of sanctions will be which governments and companies decide to continue to buy its oil. Here, Asian buyers will figure prominently.

To date, Asian players have neither panicked nor stood idle in the face of US threats to pull out of the nuclear deal. Asian end-users have been preparing for possible sharp declines in the availability of Iranian crude oil and condensate. Their supply contingency plans have included efforts to diversify their suppliers — South Korea (US), Japan (Mozambique), and India (Iraq).[53] Some traders have indicated that their existing contracts contain clauses allowing them to stop taking cargoes if sanctions were to be reimposed. Japan did not lift any Iranian crude in March, amid uncertainty over whether sovereign insurance for tankers carrying Iranian oil would be extended.[54] China, meanwhile, has hedged against overreliance on Iranian oil shipments by expanding partnerships with other suppliers within and beyond the Middle East. In fact, Russia is now China’s top foreign source of crude oil.[55]

Looking ahead to the reinstatement and possible tightening of US sanctions, buyers could continue purchasing cargoes in non-dollar currencies or through companies that do not have US subsidiaries. However, America’s Asian allies (Japan and South Korea) can reasonably be expected to accede to Washington’s approach, despite their skepticism, both because of their security dependence on the United States and their own exposure to US secondary sanctions. The course that India is likely to follow is more difficult to predict. A lot will depend on how long the White House gives Iran's customers to wind down their supply deals, the reductions benchmark it sets, and the date by which such cuts must be phased in.

China, though, could prove to be the “wild card.” China has many reasons to defend the nuclear deal — the fact that its companies have significant and growing stakes in Iran being an important one. Chinese enterprises have financed major energy projects, including helping to develop the Yadavaran and North Azadegan oilfields. In the post-JCPOA period, China has been the least hesitant of Iran’s foreign suitors, pouring investment into the country in a variety of sectors.[56] And as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) launched by President Xi Jinping has begun take shape, Iran has emerged as a major part of China’s expansive infrastructure investment plan.

Furthermore, as Harold and Nader have noted, “Iran serves as an important strategic partner and point of leverage against the United States.”[57] In light of increased US-China contention over trade and other issues, Beijing might regard the Trump administration’s sanctions campaign as a strategic opportunity, in parallel with Moscow, to consolidate its influence in the Middle East. Thus, in the months ahead, we could witness not just the latest test of the resilience of Iran’s Asian energy lifeline but a new phase of regional and global geopolitical realignment.

[1] “Growth Target at 8% in 6th Development Plan,” Financial Tribune, January 31, 2016, accessed April 30, 2018, https://financialtribune.com/articles/energy/35366/growth-target-at-8-i….

[2] “Oil, gas, petchem sectors require $200b investment: Zanganeh,” O&G Links, April 25, 2018, accessed April 30, 2018, https://oglinks.news/article/719e81/petchem-sectors-require-zanganeh?fi….

[3] “Trump Announces U.S. Withdrawal From Iran Nuclear Deal: Transcript,” New York Times, May 8, 2018, accessed May 8, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/08/us/politics/trump-speech-iran-deal.h…; and “President Donald Trump Announces His Decision On The Iran Deal At The White House,” YouTube, May 8, 2018, accessed May 8, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hqTEjriSeI4.

[4] BP Statistical Review of World Energy, London, June 2016.

[5] See UN Comtrade Staistical Database; and Pooya Azidi et al., “The Future of Iran's Oil and Its Economic Implications,” Stanford Iran 2040 Project, Working Paper No. 1, 2016, accessed April 30, 2018, https://iranian-studies.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/f…

[6] International Monetary Fund (IMF) Country Report No. 18/94, March 2018, accessed April 26, 2018, file:///C:/Users/cal/Downloads/cr1894.pdf.

[7] A detailed account of the history of the sector to 2007 can be found in P. Stevens, P. Audinet, and S. Streiffel, Investing in Oil in the Middle East and North Africa: Institutions, Incentives and the National Oil Companies (Washington, DC: World Bank/ESMAP, 2007).

[8] Vahid Dokhani and Zahra Minagar, “Iran seeks field revitalization, new development,” Oil & Gas Journal, September 5, 2016, accessed April 22, 2018, https://www.ogj.com/articles/print/volume-114/issue-9/exploration-and-d….

[9] Quoted in “NIOC Invests $65m in Oil Region Infrastructure,” Financial Tribune, April 18, 2017, accessed April 22, 2018, https://financialtribune.com/articles/energy/62604/nioc-invests-65m-in-…. Note: Following the initial success of a subsidy reduction-cash transfers scheme adopted in 2010, subsidies crept back back to the market as a result of reform mismanagement and sanctions pressure. A new round of subsidy reform was initiated in 2015, but energy prices have remained below market prices. See Dalga Khatinoglu, “Iran Plans To Drastically Raise Fuel Prices, With Risk Of Higher Inflation,” Radio Farda, December 17, 2017, accessed April 30, 2018, https://en.radiofarda.com/a/iran-raising-fuel-prices-next-year/28934040….

[10] US Energy Administration (EIA), “Under sanctions: Iran’s crude oil exports have nearly halved in three years,” June 24, 2015, accessed April 22, 2018, https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=21792; and EIA, “Iran: Country Analysis Brief,” April 9, 2018, accessed April 22, 2018, https://www.eia.gov/beta/international/analysis_includes/countries_long/Iran/iran.pdf; and International Monetary Fund Article IV Consultation, Islamic Republic of Iran, IMF Country Report No. 17/62 (February 2017) 4, accessed April 30, 2018, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2017/02/27/Islamic-Republ….

[11] US Energy Information Agency (EIA), “US Field Production of Crude Oil,” accessed April 22, 2018, https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/LeafHandler.ashx?n=PET&s=MCRFPUS2&f=M.

[12] Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI), Articles 43.8, 43.9, 44.2, and 45.

[13] Suzanne Maloney, Iran’s Political Economy since the Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015) 426-427.

[14] Benofsheh Keynoush, “Iran’s revolutionary ideology clashes with thirst for new investments,” The Guardian, August 24, 2015, accessed April 22, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/world/iran-blog/2015/aug/24/iran-revolution….

[15] David Ramin Jalilvand, “Iranian Energy: a comeback with hurdles,” Oxford Institute of Energy Studies (January 2017): 4-6.

[16] William Yong, “NIOC and the State: Commercialization, Contestation, and Consolidation in theIslamic Republic of Iran,” The Oxford Institute of Energy Studies, MEP5 (May 2015): 7, accessed April 30, 2018, https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/MEP-5.pdf.

[17] Yong, “NIOC and the State: Commercialization, Contestation, and Consolidation in the Islamic Republic of Iran,” 7.

[18] Nader Habibi, “The Economic Legacy of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad,” Crown Center for Middle East Studies, Middle East Brief, no. 74 (June 2013): 2-4, accessed April 30, 2018, https://www.brandeis.edu/crown/publications/meb/MEB80.pdf.

[19] David Ramin Jalilvand, “Iranian Energy: a comeback with hurdles,” Oxford Institute of Energy Studies (January 2017): 4-6.

[20] Benoît Faucon and Asa Fitch, “Iran’s Guards Cloud Western Firms’ Entry After Nuclear Deal,” The Wall Street Journal, July 21, 2015, accessed April 22, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/irans-guards-cloud-western-firms-entry-after-nuclear-deal-1437510830; and Tamer Badawi, “Iranian Economic Reform Between Rouhani and the Guards,” CEIP Middle East Analysis, August 12, 2015, accessed March 14, 2018, http://carnegieendowment.org/sada/?fa=60999.

[21] As per the buyback contract (BBC) model, upon commencement of production, operatorship reverted back to the NIOC, which used the sales revenue to pay back the IOCs for their capital expenditures. IOCs did not obtain equity in the fields; and the annual repayment rates to them were based on predetermined percentages of the field’s production and rate of return. See Maximilian Kuhn and Mohammadjavad Jannatifar, “Foreign direct investment mechanisms and review of Iran’s buy-back contracts: how far has Iran gone and how far may it go?” The Journal of World Energy Law & Business 5, 3 (2012): 207–234.

[22] The new Iranian Petroleum Contract (IPC) contains terms similar to a Production Sharing Agreement (PSA). Companies will not be permitted to own reserves, but will be able to establish joint ventures with NIOC, or its subsidiaries, to manage the entire project life cycle. Companies will have a longer time period of between 20 to 25 years to explore, develop and produce from a field, with the possibility to extending it to the Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) phases.

[23] For a good discussion of the new IPC framework, see “The Biggest Obstacle to Iran’s Energy Makeover is Itself,” Stratfor, May 27, 2016, accessed March 12, 2018, https://worldview.stratfor.com/article/biggest-obstacle-irans-energy-ma….

[24] See for example, Golnar Motevalli, “Iran Cancels London Summit for New Oil Deals,” Bloomberg, January 30, 2016, accessed March 14, 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-01-30/iran-s-new-oil-deals….

[25] “Iran’s oil ministry hopes nuclear deal can hold as oil exports climb,” Platts, April 30, 2018, accessed April 30, 2018, https://www.platts.com/latest-news/oil/tehran/irans-oil-ministry-hopes-….

[26] Andy Tully, “Saudi Arabia Continues to Ramp Up Oil Output in Face of Market Glut,” OilPrice.com, December 21, 2015, accessed April 22, 2018, https://oilprice.com/Energy/Crude-Oil/Saudi-Arabia-Continues-to-Ramp-Up….

[27] Tsvetana Paraskova, “Iran’s Oil Exports Hit Record High as Sanctions Loom,” Oilprice.com, May 1, 2018, accessed May 1, 2018, https://oilprice.com/Energy/Energy-General/Irans-Oil-Exports-Hit-Record….

[28] Angelina Radcouet, “Iran’s Surge in Exports Doesn’t Mean Output Is on the Rise,” Bloomberg, May 3, 2018, accessed May 4, 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-05-03/iran-s-surge-in-oil-….

[29] Gordon Kristopher, “Iran’s Oil Sanctions Lifted: Brent Oil Prices Feel the Heat,” Market Realist, January 18, 2016, https://marketrealist.com/2016/01/irans-oil-sanctions-lifted-brent-oil-….

[30] Benoit Faucon, “Iran’s Oil Boom Hasn’t Showed Up,” The Wall Street Journal, March 7, 2018; and Neanda Salvaterra, “Iran’s Oil Industry Is Still Waiting for Cash Infusion—Energy Journal,” The Wall Street Journal, March 8, 2018.

[31] The South Pars II project was originally awarded to CNPC in 2010, which withdrew from it in October 2012. In July 2017, Total took over the project as operator, with CNPC as minority partner (30%) and Iran’s Petropars having a 20% stake.

[32] David Ramin Jalilvand, “Progress, challenges, uncertainty: ambivalent times for Iran’s energy sector,” Oxford Energy Insight 34 (April 2018), accessed April 21, 2018, https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Progress-challenges-uncertainty-ambivalent-times-for-Iran%E2%80%99s-energy-sector-Insight-34.pdf; and See for example, Golnar Motevalli, “Iran Cancels London Summit for New Oil Deals,” Bloomberg, January 30, 2016, accessed March 14, 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-01-30/iran-s-new-oil-deals….

[33] “Iran and Russia sign deal to develop two oilfields - Iranian state TV,” Reuters, March 14, 2018, accessed March 14, 2018, https://in.reuters.com/article/iran-russia-oil/iran-and-russia-sign-dea….

[34] International Energy Agency, World Energy Outlook 2040, http://www.iea.org, accessed April 30, 2018.

[35] Whitney Eulich, “What sanctions? Top five countries buying oil from Iran,” Christian Science Monitor, February 17, 2012, accessed April 22, 2018, https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Middle-East/2012/0217/What-sanctions-To…,

[36] “Iran Sanctions,” CRS Report for Congress, November 17, 2018, 44-46, accessed April 22, 2018, https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20171121_RS20871_17a9984e6646e1ebb3028c603adcfcff03a0c49f.pdf.

[37] Catherine D. Cimono-Isaacs and Kenneth Katzman, “Iran’s Expanding Economic Relations with Asia,” CRS Insight, November 29, 2017, 1-2, accessed April 22, 2018, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/mideast/IN10829.pdf.

[38] Iran Sanctions,” CRS Report for Congress, 45.

[39] Najmeh Borzorgmehr, “China ties lose lustre as Iran refocuses on trade with west,” Financial Times, September 23, 2015, accessed April 30, 2018, https://www.ft.com/content/9d1564bc-603f-11e5-a28b-50226830d644.

[40] See Itt Thirarath, “Iran's Big Asian Oil Customers Return,” Middle East-Asia Project (MAP), August 23, 2016, accessed April 22, 2018, http://www.mei.edu/content/map/irans-big-asian-oil-customers-return.

[41] “Iran’s Oil Exports Near 1 Billion Barrels in 2017,” Financial Tribune, January 1, 2018, https://financialtribune.com/articles/energy-economy/79082/irans-oil-ex….

[42] “Iran’s March oil exports fall to two-year low as Asia demand eases – source,” Reuters, March 9, 2018, accessed April 30, 2018, https://af.reuters.com/article/commoditiesNews/idAFL4N1QR0BO.

[43] Umud Niayesh, “Japan reveals data of its oil imports from Iran,” Trend News Agency, April 30, 2018, LexisNexis.

[44] Nidhi Verma, “Iran deepens freight discount to boost oil sales to India: sources,” Reuters, February 17, 2018, accessed March 12, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-iran-oil/iran-deepens-freight-discount-to-boost-oil-sales-to-india-sources-idUSKCN1G10T4; and “Iran pushes to retain Asia oil buyers as possible U.S. sanctions loom,” Reuters, November 27, 2017, accessed March 14, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-asia-iran-oil/iran-pushes-to-retain-….

[45] Florence Tan, “Iran cuts April crude prices for Asia in fight for market share,” Reuters, March 8, 2018, accessed April 30, 2018, https://www.nasdaq.com/article/iran-cuts-april-crude-prices-for-asia-in….

[46] Aaron Sheldrick, “Asia’s March Iran oil imports hit five-month high,” Reuters, April 27, 2018, accessed April 30, 2018, https://uk.reuters.com/article/asia-iran-crude/asias-march-iran-oil-imp….

[47] State refiners including Indian Oil Corp, Mangalore Refinery and Petrochemicals Ltd, Hindustan Petroleum Corp and Bharat Petroleum Corp, along with it subsidiary Bharat Oman Refineries Ltd, lifted about 27 percent less. Some reports attribute this drop to a row over development rights to the Farzad-B natural gas field. See “India’s Iran oil imports fell 15.7 pct in fiscal year 2017/18 – trade,” Reuters, April 20, 2018, accessed April 22, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/india-oil/indias-iran-oil-imports-fell-15-7-pct-in-fiscal-year-2017-18-trade-idUSL3N1RV552. See also Nidha Verma and Sanjeev Miglani, “Iran’s Rouhani seeks Indian investment amid U.S. pressure,” Reuters, February 14, 2018, accessed March 14, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-iran/irans-rouhani-seeks-india….

[48] Nidhi Verma, “Indian state firms plan to nearly double Iranian oil imports: sources,” Reuters, April 6, 2018, accessed May 2, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-iran-oil/indian-state-firms-pl….

[49] Dhwani Pandya and Debjit Chakraborty, “Iraq is New Oil King, Beats Saudis in World’s Fastest Growing Market, Bloomberg, June 14, 2017, accessed April 30, 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-06-14/iraq-beats-saudis-to….

[50] Wael Mahdi, Saket Sundria, Annmarie Hordern, and Debjit Chakraborty, “Saudis See Strong Oil and Look to Secure Sales in Prized Market,” Bloomberg, April 11, 2018, accessed April 30, 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-04-11/saudis-see-strong-oi….

[51] International Crisis Group, “The Nuclear Deal at Two: Status Report,” Crisis Group Middle East Report No. 181 (January 2018), accessed April 30, 2018, https://d2071andvip0wj.cloudfront.net/181-iran-charts-survey.pdf.

[52] Iran’s past “sanctions coping” measures were wide-ranging. They included sanctions restriction-evasion techniques such as the falsification of records and creation of front companies.

[53] “Asian Oil Importers Ready to Sail through Iran Sanctions Storm,” Energy Monitor Worldwide, April 28, 2018, LexisNexis, May 1, 2018.

[54] Osamu Tsukimori, “Iran’s March oil exports fall to two-year low as Asia demand eases: sources,” Reuters, March 9, 2018, accessed April 26, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-iran-oil-exports/irans-march-oil-exp….

[55] See US Energy Information Agency (EIA), “China Surpassed the United States as the world’s largest crude oil importer in 2017,” February 5, 2018, accessed May 6, 2018, https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=34812#.

[56] “China pumps billions into Iranian economy as Western firms hold off,” Reuters, December 17, 2017, accessed April 30, 2018, http://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy-defence/article/2122435/china-….

[57] Scott W. Harold and Ali Nader, “China and Iran: Economic, Political, and Military Relations,” RAND Corporation (2012): 15, accessed April 30, 2018, https://www.rand.org/pubs/occasional_papers/OP351.html.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.