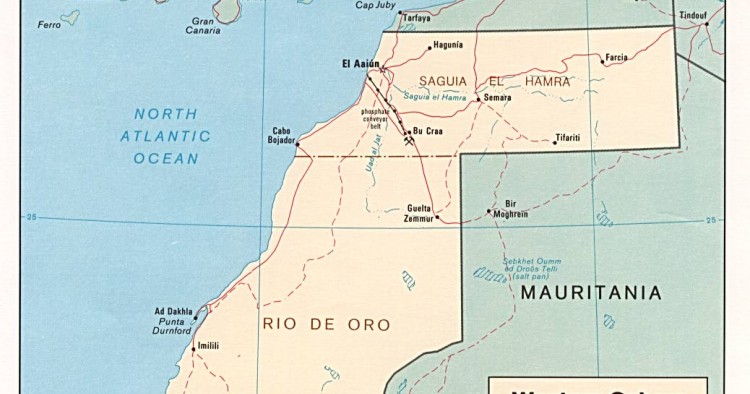

1) Origins and genesis of the conflict

Since the origin of the crisis, it has been evident that Morocco would never accept any outcome that might contest its sovereignty or result in the independence of the Western Sahara. The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) proposed in its first resolution adopted on December 16, 1965 that Spain “takes all necessary measures” to decolonize the territory, while entering into negotiations on “problems relative to governing.”

Following this first step, the UNGA adopted seven resolutions between 1966 and 1973 reiterating the need to hold a referendum on self-determination, in line with the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples. Nevertheless, King Hassan II has consistently advocated that Western Sahara was part of the Kingdom. This became crystal clear when Spain announced its plan to organize such a referendum in early 1975; King Hassan II immediately referred the case to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and called for the “Green March” the day after the publication of the Court opinion.

After several years during which the Organization of African Unity (OAU) tried unsuccessfully to solve the conflict following the Moroccan initiative, UN Secretary General Pérez de Cuellar convinced King Hassan II on July 20, 1985 to accept a referendum on the self determination of the inhabitants of Western Sahara under UN auspices. A negotiation followed which led to the adoption of the UN Settlement Plan that went into effect in April 1991.

During this entire period, either before or after any agreement or negotiation, the Moroccan authorities have never left any doubt that they had a very restrictive interpretation of the referendum as a “confirmation” of continued Moroccan sovereignty.

2) Autonomy and/or Referendum

Conscious of that essential and unavoidable factor, Mr. Pérez de Cuellar seems to have been convinced early in the process that autonomy could be a preferable and more practicable option for Western Sahara.

Nevertheless, the process engaged under the UN Settlement Plan, and, in particular, the Voter Identification Process for the self-determination referendum has been going on for almost a decade but went nowhere due to the parties’ procrastination, the intricacies of their political goals, or other constraints. Despite all efforts made by Special Representative James Baker III from March 1997 to April 2004, his mediation could not achieve any concrete result as long as the notion of a referendum on independence has remained as a part of any of the options proposed.

3) Autonomy as the optimal political solution

It is also important to remember that in its Resolution 154 adopted on April 20, 2004 the UN Security Council recalls that “a mutually acceptable political solution” is the only way out. Thus, it was and remains useless to hope or expect any formal and forceful decision by the Security Council which would try to impose and enforce any Peace Plan not agreeable to the parties, in particular to Morocco.

It has always been evident that key members of the Security Council, for fear of triggering a regional conflict or undermining the Moroccan regime, would refrain from imposing the mandatory organization of a referendum by the UN whose result, being unacceptable to one party, might eventually lead to a new international crisis. None of these countries would like to be faced with such a situation in which the Security Council would have to condemn one party as well as to consider the option of a military intervention in Western Sahara.

In reality, like for Kashmir or Cyprus, maintaining the status quo with a symbolic presence of UN forces continues to satisfy most Security Council members.

4) Referendum on autonomy

This is why autonomy still appears to be the only possible option if one wants to get the acquiescence of Morocco, it being understood that this can be achieved through an accommodation with Algeria and the Polisario Front.

For a long time, Morocco’s approach to the notion of autonomy for Western Sahara took the form of a mere extension of a process of decentralization of State power that would have indistinctly covered all the regions of the Kingdom. Such an approach seems inadequate insofar as Rabat could not accept the transfer of real and important powers to every region, in particular the northern part of the country. But in the case of Western Sahara, it would be impossible to offer a solution that would reduce the devolution of attributions already foreseen in the Framework Agreement[1] as well as in the Moroccan proposal.

In order to reach a global agreement it may be necessary to keep the notion of referendum on the table, but everyone should understand that such a ballot could not clearly include the option of independence, unacceptable to Morocco, but it could deal with the nature and degree of powers devolved to this territory.

Concurrently, it is hard to imagine that Algeria and the Polisario Front would be willing to endorse the full sovereignty of Morocco in such an agreement. Therefore, it might be useful to leave open the question of the interpretation of the ICJ Opinion. In this context, the implementation of the agreement should be followed by the Security Council and reassessed after a few years.

[1] Draft Framework Agreement on the Status of Western Sahara, presented by James Baker to Morocco and Polisario/Algeria in 2001; the Framework Agreement provided for autonomy for five years without including a final referendum on the status of Western Sahara.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.