Since the Taliban seized control of Kabul on Aug. 15, Russia has expanded its engagement with India and Pakistan on Afghanistan. Russian President Vladimir Putin held talks with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Aug. 24, which resulted in the creation of a permanent bilateral channel for consultations on Afghanistan. On Sept. 8, Modi’s national security advisor, Ajit Doval, met with his Russian counterpart, Nikolay Patrushev, and agreed to expand Russia-India cooperation against terrorism and drug trafficking. On Aug. 25, Putin spoke with Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan about the situation in Afghanistan, which resulted in Khan inviting Putin to visit Pakistan.

Russia’s simultaneous engagement with India and Pakistan on Afghanistan is the latest iteration of its balancing strategy toward the two South Asian rivals. Russia’s June 2002 offer to mediate between India and Pakistan set this balancing strategy into motion, and it has strengthened since Prime Minister Mikhail Fradkov’s April 2007 visit to Islamabad thawed the historically fractious Russia-Pakistan relationship. Notwithstanding its efforts to maintain close ties with New Delhi and Islamabad, Russia will likely find greater common ground with India than Pakistan in Afghanistan in the months ahead.

Prospects for Russia-Pakistan cooperation in Afghanistan

After the Taliban’s overthrow in December 2001, Russia-Pakistan dialogue on Afghanistan focused almost exclusively on mitigating immediate threats. In 2012, Russia’s envoy to Afghanistan Zamir Kabulov held talks with Pakistan about reining in Central Asian militant groups, such as the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan and Islamic Jihad, which tried to enter Tajikistan and Uzbekistan from their bases in northern Afghanistan. The extent of Russia-Pakistan coordination broadened in 2016, as Russia, China, and Pakistan created a trilateral format to discuss stabilizing Afghanistan and counterterrorism strategy. In December 2016, Russia, China, and Pakistan held talks on combatting Islamic State-Khorasan Province (ISKP), which were widely criticized in the U.S. for excluding the Afghan government.

The inauguration of the Moscow-format peace talks on Afghanistan in 2017 gave Pakistani officials the opportunity to engage with their Russian counterparts alongside representatives from China, Iran, India, and Central Asia. This engagement caused Pakistan to express solidarity with Russia against U.S. claims that Moscow was legitimizing the Taliban. In April 2017, Tariq Fatemi, a key foreign policy aide to Pakistan’s Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, claimed that Russia was “positively” using its influence over the Taliban to convince it to participate in peace talks. Fatemi also urged the U.S. to participate in the Moscow-format talks.

Pakistan’s emphasis on Russia’s growing presence in Afghanistan also had self-interested motives, as it wished to alarm the U.S. and deflect from allegations that it supported the Taliban. In March 2017, Pakistani military sources warned about potential Russian military involvement in Afghanistan, and in October 2017, Pakistani Foreign Minister Khawaja Muhammad Asif implied that Russia had more influence over the Taliban than Pakistan. Nevertheless, cooperation between Moscow and Islamabad continued to expand, as both countries participated in the extended troika format on Afghanistan and interacted in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Russian officials also defended Pakistan against terrorism sponsorship allegations. On July 29, Kabulov stated that Pakistani officials did not wish to turn Afghanistan into an Islamic Emirate, as a Taliban triumph would inspire extremist forces within Pakistan.

Despite this uptick in bilateral engagement, Pakistan’s role in Afghanistan has given rise to mixed perceptions in Russia. Andrew Korybko, a Moscow-based political analyst, hailed the Aug. 25 Putin-Khan phone call as a “defining moment” in Russia-Pakistan relations, as it was the first time that Russia acknowledged that it needed Pakistan to advance its interests. Russian media outlets have criticized Pakistan’s support for the Haqqani network as potentially corrosive to Afghanistan’s sovereignty, and the Taliban’s appointment of Sirajuddin Haqqani as interior minister will likely amplify these concerns. Sputnik Dari, Russia’s state media bullhorn in Afghanistan, has uncritically promoted allegations of Pakistani military involvement in the Panjshir Valley. This suggests that frictions between Russia and Pakistan could surface, even as both countries praise their respective roles in Afghanistan.

Prospects for Russia-India cooperation in Afghanistan

Although Russia-India relations have strengthened over the past decade, cooperation between the two countries on Afghanistan has been relatively small scale. In November 2018, India sent Amar Sinha, who served as ambassador to Afghanistan from 2013-16, and T.C.A. Raghavan, a former high commissioner to Pakistan, to the Moscow-format talks. India’s dispatch of these senior ex-diplomats was noteworthy, as it broke with New Delhi’s long-standing policy of avoiding diplomatic engagement with the Taliban. However, their participation in the Moscow-format talks was limited, as both diplomats did not make statements at the conference and served as mere observers.

Disagreements between Russia and India on Afghanistan have also periodically surfaced. In June 2020, Kabulov claimed that “New Delhi’s policy of avoiding any engagement with the Taliban has had its day” and asserted that the Taliban had abandoned some of its “radical and jihadist principles.” This narrative, which dovetailed with Russia’s belief that the Taliban was a credible bulwark against ISKP, has received pushback in New Delhi. Brig. Gen. Venkataraman Mahalingam, a prominent Indian defense analyst, recently told me that, “Russia’s imagination that the Taliban (an aligned group of al-Qaeda) will fight ISIS and spare Russia from terrorism is misplaced. They have failed to see the difference between Taliban’s tactical moves and their long-term involvement in ‘Islamic Jihad.’” Russia also repeatedly excluded India from the extended troika, and Kabulov stated that New Delhi’s role in Afghanistan would be confined to its “post-conflict development.”

Despite this history of limited cooperation and periodic disagreements, the future of Russia-India cooperation in Afghanistan is brighter. The Doval-Patrushev meeting is expected to facilitate an expansion of intelligence cooperation between Russia and India in Central Asia. Russian Ambassador to India Nikolay Kudashev’s emphasis on a possible spillover of violence from Afghanistan to Kashmir underscores this potential for cooperation. Anil Trigunayat, who served as India’s ambassador to Libya, Malta, and Jordan, and as deputy chief of mission at the Indian embassy in Moscow from 2010-12, shares this optimism. Trigunayat acknowledges that Russia views India’s grassroots-level public acceptance in Afghanistan as a significant asset and stated that, “Putin’s appreciates India’s concerns with regard to the likely spread of terrorism in South and Central Asia, and India is the only in this for them.”

After assiduously balancing close relations with India and Pakistan for over a decade, Russia is primed to cooperate with both countries against the threats posed by a Taliban-led Afghanistan. Given the polarizing nature of the Afghanistan crisis in Islamabad and New Delhi, Russia will have to tread cautiously to avoid alienating either of its South Asian partners.

Samuel Ramani is a tutor of Politics and International Relations at the University of Oxford, where he received his doctorate in March 2021. His first book on Russia’s foreign policy towards Africa will be published by Oxford University Press and Hurst and Co. in 2022. Follow Samuel on Twitter @samramani2. The opinions expressed in this piece are his own.

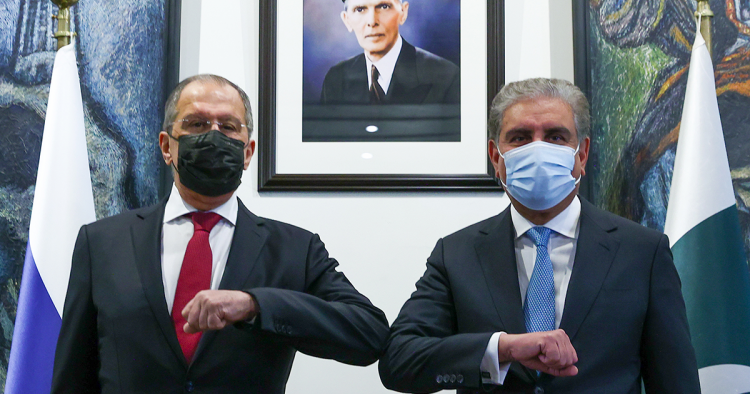

Photo by Russian Foreign Ministry\TASS via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.