Summary

It’s been nearly three years since the Turkish military incursion into northern Syria in August 2016, but one central question remains unanswered: What is Ankara’s plan for the area now under its control? In an effort to shed light on the answer, this paper examines the complex relationship between local governance and service provision in the Euphrates Shield (ES) area of north Aleppo and the Turkish state.

There are countless articles and reports detailing various business deals, infrastructure projects, and sources of funding for towns in ES; therefore, this paper is not intended to provide a comprehensive overview of the current status of governance and infrastructure development in the region. Instead, it uses secondary sources and interviews with Syrian and Turkish activists and officials to uncover the complexity of Turkey’s relationship with north Aleppo and establish that, first and foremost, Turkey has no coherent policy with regards to local governance in ES. Turkish state institutions walk the line between co-option and support when it comes to specific aspects of civil society and governance structures, but any decisions by Turkish officials are overwhelmingly being made at the provincial level by governors and vice-governors, not by Ankara. The hope is that this paper will provide valuable analysis for further research into the future trajectory of north Aleppo.

The rise of local councils

The Syrian government has not controlled large swathes of the country for more than six years. In its absence, communities have sought to create stability and provide for basic needs by establishing local councils. These mostly exist in rural towns, but have also been formed in neighborhoods, cities, and at the governorate level. However, since 2016, because Damascus has recaptured much of the country, the number of local councils has decreased dramatically. According to the Omran Center for Strategic Studies, there were only 317 legally recognized opposition-run local councils in January 2018, compared to 940 in 2015.1 Following the regime’s capture of all opposition pockets in Damascus, Homs, and southern Syria throughout the spring of 2018, this number dropped further, to just over 200.

Omran’s 2016 survey of 105 local councils in opposition-held territory found that 57 percent of local councils were formed through “a general agreement on a local level,” and 38 percent were formed through elections, with the lack of security and legal expertise cited as the major reasons why more elections were not held.2 This claim is supported by other surveys as well.3 The majority of these councils were created in 2012 and 2013 and go through restructuring on average once a year.4

Bashar al-Assad legalized local councils as part of his reform package at the beginning of the Syrian uprising. Decree 107, promulgated on Aug. 23, 2011, called for the establishment of “local administrative bodies [to] manage issues at the provincial and municipal levels” in an attempt to “promote decentralization” and “improve society at the local level."5 The decree has since formed the basis on which all local councils — regime, opposition, and Kurdish — have been established, and by which reconciled towns maintain a small degree of independence.6 There are four distinct environments in which these local councils exist today: (1) Those controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in the northeast, (2) regions under regime control, (3) towns which were formerly opposition-held, but have since reconciled with the regime, and (4) towns that remain in opposition hands. This paper will focus on the latter environment as it attempts to understand the effect of Turkish intervention in northern Syria.

On Aug. 24, 2016, the Turkish military and their FSA allies launched Operation Euphrates Shield, officially entering the northern Aleppo region — the first time Turkish forces had done so in nearly 100 years. In the three years since, Turkish military and governmental institutions have embedded themselves, to varying degrees, in north Aleppo, Afrin, and Idlib. The Turkish military and governmental presence in north Aleppo represented the final stage in the brief, but fraught, history of local governance in the region. First under the control of local FSA factions, then ISIS, and finally the Turkish-backed FSA and national-Islamist armed groups, the local governments and civil society of cities like Azaz, al-Bab, and Jarabulus are finally seeing a sustained period of peace in which institutions can grow and evolve.

According to Omran’s 2018 report, 27 local councils legally recognized by the Syrian Interim Government (SIG) govern at least 350,000 people in the ES area of north Aleppo:

"These were formed mostly through a communal selection or election agreements … [and] are supported and directly protected by an international actor with its military presence (Turkey). The majority of these councils adopt and advocate for an administrative decentralization system of governance with little appetite or aspiration for political decentralization in future Syria."7

These councils appear to be the best funded of all opposition councils, with 70 percent of residents paying taxes and 135 donors providing “livelihoods and early recovery/infrastructure” in 2017. The donors include governments as well as local and international aid organizations. The number of donors and the relative security within which councils in ES operate has created a high degree of financial stability and enabled the councils to pursue more infrastructure projects than those in other regions.8

The extent to which local governance in north Aleppo differs from that in greater Idlib is largely dependent on the extent to which Turkish institutions have co-opted or supported local institutions in the region under their control. Co-option and support are two distinct forms of intervention. Simply put, co-option refers to Turkish institutions replacing their Syrian counterparts, while support can mean anything from funding and training to working alongside local Syrians.

Renewed development after Euphrates Shield

On Sept. 8, 2016, Gaziantep mayor Fatima Şahin arrived in the Syrian town of Jarabulus just two weeks after it was liberated from ISIS.9 Şahin was the first Turkish government official to step foot in Syria since 2011, and her arrival heralded the beginning of a renewed relationship with the Syrian communities that would be liberated with the help of the Turkish Armed Forces over the next seven months. By that time, Turkey’s Disaster and Emergency Management Authority (AFAD) had already begun digging new wells for the town’s 15,000 residents, chlorinating existing wells, and providing generators for water pumps.10 Simultaneously, a Turkish electrical company began laying 3 km of new lines from the border town of Karkamış that would supply 31.5 KW of electrical power for Jarabulus.11 Şahin also offered the potential of connecting Jarabulus to Karkamış’ water supply in the event that its wells were not sufficient.12 Meanwhile, the Turkish Ministry of Health set up a medical tent with an ambulance and a rescue medical team, as well as Turkish doctors and health workers to provide for local Syrians and internally displaced persons (IDPs) living just outside the city.13

The speed with which Turkish state institutions entered Jarabulus and began working on crucial infrastructure repair projects suggests that Turkey had anticipated and prepared for the basic governance needs of the region. However, one Syrian NGO operating several projects in ES claims that the Turkish government was slower to roll out civil society assistance than military policies in ES. The interviewee stated that Turkey did not begin coordinating with donors and international NGOs (I-NGOs) until after the operation had already began. Interestingly, when it came to Afrin in early 2018, Turkey began planning for post-conflict stabilization projects with donors and I-NGOs prior to any military action. The interviewee further stated that reconstruction work in the ES area is for the most part carried out by Syrian businesses, not Turkish ones, and that any Turkish businessperson who wants to operate in north Aleppo must have a Syrian partner.14

Regardless of who is carrying out the bulk of the work, satellite imagery makes clear the extent of the aid delivered to north Aleppo through Turkey. Between Nov. 29, 2016 and Dec. 9, 2016, Jarabulus’ soccer field was turned into a 12,000-square-meter storage area with 43 new buildings (Figure 1). Unfortunately, high-quality satellite imagery of the Karkamış border crossing is not available until March 3, 2017. However, between March 3, 2017 and May 24, 2017, nearly 300 semi-trucks and flatbeds were parked or moving along just 2 km of road between Jarabulus and the border (Figures 1 and 2). Interestingly, it was not until June 20, 2018 that the Gaziantep Chamber of Commerce officially reopened this border crossing to both Turkish and Syrian merchants.15 It would, therefore, seem that all of the traffic in the below pictures consisted of aid delivery overseen, or at least explicitly allowed, by the Turkish government.

The infrastructure required to deliver this much aid to northern Syria was significant, and new building projects were carried out on the Turkish side of the border to address this. An empty field on the northern edge of the small town of Kıvırcık, just 4 km from the border, was turned into a 46,000-square-meter-plus parking lot for nearly 300 semi-trucks (Figure 3). This parking lot appears to have been used between July 2017 and October 2017 and has remained empty since then.

In the nearby town of Soylu, another empty field was rapidly developed following the Turkish intervention. On Sept. 10, 2016, a small dirt parking lot was graded and quickly filled with military vehicles. In December, construction began again, and by May 2017, more than 80 structures had been built, including warehouses of 1,300 and 750 square meters (Figure 4). It is unclear if this area has a military or civilian use, however. Similarly, in a large industrial park just south of Nizip — a mid-sized Turkish city situated half-way between Gaziantep and Jarabulus — more than 34,000 square meters of new warehouses were built in the second half of 2017 (Figure 5). It should be noted that there is no information confirming a direct link between the development in Nizip and trade in north Aleppo.

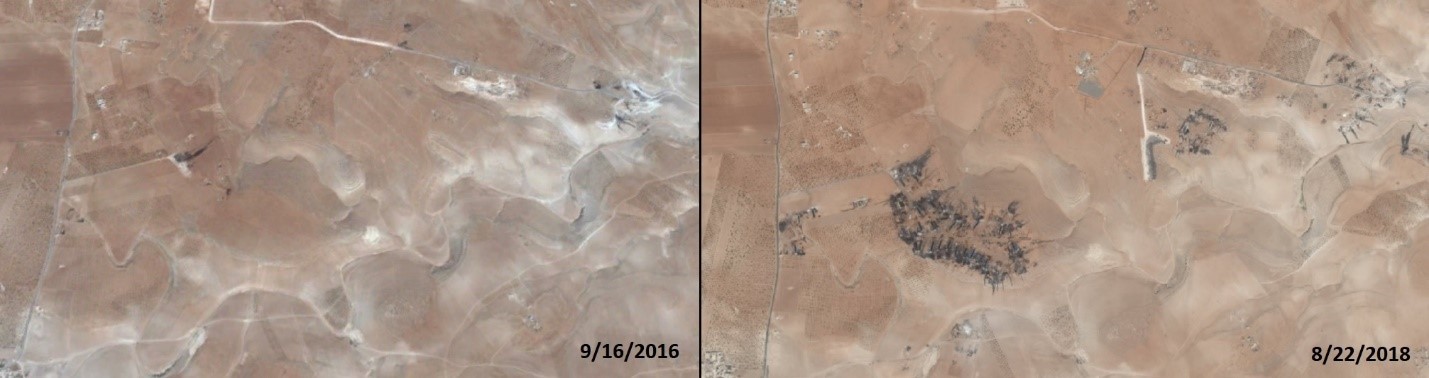

Development within ES is also visible via satellite. In particular, two large-scale primitive oil refineries have appeared. The rapid creation and expansion of these refineries is just one indicator of the degree of infrastructure material, whether coordinated by Turks or Syrians, flowing into ES from Turkey. Refineries under ISIS control are almost always small and widely dispersed to ensure that no single airstrike can cause too much damage to this crucial revenue source. A few scattered refineries are thus visible in this area prior to the Turkish operation (Figure 6, left). However, the refinery southwest of Jarabulus near the village of Tall Shair was rapidly developed following Turkey’s intervention.16 By February 2017, more refineries were being built and improvements and construction at the site continues today (Figure 6, right).

A second refinery was built south of Umm Routha, just north of the Manbij pocket (Figure 7). Construction on this refinery began in late January 2017, and the facility now encompasses some 140,000 square meters. Less than a quarter mile from the northwestern edge of the refinery sits a large Turkish military outpost. It is not possible to determine the size of either operation without more information; however, a brief examination of other makeshift refineries in the oil-rich governorates of al-Hasaka and Deir ez-Zor reveals that these refineries — located in both Kurdish-and regime-held territories — are much smaller and often have empty cooling pools, indicating a lack of production compared to those in ES.

Importantly, this region of north Aleppo does not have oil, especially the amount of oil that would require such a large facility. Instead, there is an agreement in place to transport crude oil from the SDF-held governorate of al-Hasaka to the regime-held Latakia, Tartous, and Homs governorates, which includes a line delivering oil to Jarabulus.17 Satellite imagery also reveals the large-scale oil trade between these two regions: Imagery from Feb. 2, 2019 shows hundreds of oil tankers on the road and dirt parking lots in the town of Umm al-Julud on the border between SDF- and Turkish-controlled areas of east Aleppo, and just 23 km southwest of Jarabulus.18

Further imagery from March 29, 2017 shows a line of oil tankers crossing from the Manbij pocket to the frontline town of Tukhar Shagir, just south of the Umm al-Routha refinery. Once delivered, the crude oil is treated in the makeshift refineries documented above, as well as additional refineries north of al-Bab, and then sold in the areas controlled by the Turkish-backed FSA or on the black market to the SDF-controlled area of Manbij.19 Thus, it appears that at least part of the ES region is still heavily tied into broader Syria — in fact, the oil trade may be the only major thing connecting all three of Syria’s separately held regions. It is important to note that every Syrian and Turk interviewed for this project denied the existence of oil trade between north Aleppo and the SDF-held northeast, revealing just how contentious and politically dangerous this industry is deemed to be by Turkey.

Turkey invests

“The investment reality in rural Aleppo cannot be seen as separate from the reconstruction file in Syria, which Turkey is trying to be part of. … It attempts to prove its presence in the area economically via the enterprises it officially announced, in addition to the projects which private companies seek to implement following a different mechanism."20

Aside from this major economic tie to the rest of Syria, most of the ES region’s economic and institutional links appear to be oriented inward and north. According to a report by the Syrian opposition paper Enab Baladi, Syrians in rural north Aleppo “are studying Turkish in schools, and they are buying Turkish products and driving their cars on highways built by Turkey,” while “identity cards given to citizens in several areas of the northern countryside of Aleppo, carrying the person’s credentials … are directly connected to the Turkish Civil Register."21 Turkey is reportedly fully funding and overseeing the construction of a series of highways linking the town of al-Rai first to the nearby al-Rai border crossing, and then to the major border towns of Azaz and Jarabulus, as well as a third highway linking al-Rai with al-Bab to the south.22 This project is reported to cost 60 million Turkish lira (around $10 million), and is designed to help link the economies of all major towns in ES to merchants in southern Turkey while also alleviating the traffic crisis in al-Rai caused by the nearly 200 trucks crossing the border daily.23

Despite the heavy presence of Turkish officials and workers in ES, “Mohammed” — who did not wish to use his real name — of the Assistance Coordination Unit (ACU) claims that this highway project is one of only two major projects undertaken by the Turkish government. According to Mohammed, the other involves building a large hospital complex. Both are being carried out with only loose coordination with their respective local councils.24

According to the minister of services for the SIG, local councils in ES work directly with Turkish businesses to organize development projects.25 Rather than organizing them through the SIG, each local council works through the Turkish government to find Turkish contractors to meet various needs.26 The fact that local councils must work directly with Turkish businesses is almost certainly a direct result of the SIG’s absence from every local council in the region — a consequence of the SIG’s largely irrelevant role in the war today. In an interview with an Azaz local council member conducted by Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi on March 10, 2019, the interviewee claimed that “all the councils, and not only the Azaz council, [work directly with Turkey], and that is because of the absence of the role of the [interim] government and the provincial council."27

A second interview conducted by Tamimi with a former member of the Ehtemlat local council confirmed this. In that interview, the interviewee claimed that the SIG only held an affiliation with the “central council,” but that the SIG is “absent” from this council.28 According to the interviewee, the central council is a regional body that oversees several individual local councils in the area and includes Turks.29 For example, the local councils of Ehtemlat and its neighbor Sawran would both technically operate under the purview of a larger “central council” in which Turkish officials, it is claimed, are present. This author’s interviews with Syrian NGOs operating in the region have further confirmed the absence of the SIG.

Therefore, local councils work with Turkish companies and I-NGOs to implement necessary infrastructure projects. Enab Baladi highlights how this dynamic has played out in several cases:

"This policy has resulted in several economic agreements for local councils, including the supply of electricity to the city of Azaz through the Turkish private company ET Energy and the project of ‘residential suburb of Qabasin’ between the city council and Göktürk Establishment and Construction Company. Al-Bab City Council laid the foundation stone for the first industrial city in the area under Turkish support, with an area of 56,100 square meters, and signed a contract with Euro Beton to build a cement quarry. In mid-August, al-Bab City Council received two electricity supply offers: The first from a private Turkish company and the second was directly offered by the Turkish government."30

PTT, which operates Turkey’s postal service and provides banking services, opened its first branch in Jarabulus in October 2017 and a second branch in Azaz in April 2018.31 Türk Telekom has also been working alongside the Azaz local council to update cell towers in the region. All these projects employ locals; further, all Syrians associated with Turkish-backed development projects, Turkish-supported military and police forces, teachers, and local council employees are now paid in Turkish lira, intimately tying Syrian life in ES to Turkey’s political and economic situation.32

In Azaz, Turkey’s ET Energy has entered a 10-year, $7 million contract with the local council to build a 30-MW power station in the town. The Turkish town of Kilis, just over the Syria-Turkey border, has agreed to mediate any disputes that arise between the local council and ET Energy, while the local council is responsible for mediating between the company and residents. ET will install meters in every house and PTT will process residents’ payments to the company — in lira. The Azaz local council will take just 1% of the profits. This same pattern is playing out across ES: In Qabasin, where the Turkish company Göktürk is building a new residential district with 225 apartments and 30 shops, the local council is again only responsible for providing the land while the private company will oversee all other aspects of the project.33

However, crucial services like water and gas have yet to be developed in sufficient quantities across the ES region. Although several water infrastructure projects have been discussed or planned, all of them have been canceled or put on hold.34 Reasons for this vary from lack of funding, to a lack of willing Turkish contractors. One thing remains clear though: Turkish companies are more than willing to engage in development projects that are profitable, even if they are not necessary.

The relationship between these local councils and the Turkish government seems to extend only so far as the latter providing salaries for local council members (1,200 lira per month) and implementing “high urgency projects like water or electricity."35 The Turkish government does not otherwise fund local councils or their projects, and funds for paying Turkish or Syrian businesses to carry out construction contracts must be obtained from I-NGOs more often than not.36 What this illustrates is the steep limitations to Turkey’s willingness to engage directly — central government to local government — to develop the ES region; it instead has chosen to empower private businesses and local Turkish governments (discussed in the below section) to deal directly with Syrian local councils. The only exceptions to this appear to be Turkey’s role in developing education and health services in the region, overseeing IDP camps, and training and funding the Free Syrian Police (FSP).

Branches of the Turkish government have stepped in when it comes to education and medical services in the region. In January 2018, Gaziantep University opened an official branch in Jarabulus, and the Jarabulus local council has regularly published its student data (names, family, home, etc.) in both Arabic and Turkish.37 Al-Bab’s local council also made a deal to open a local branch of Harran University, based in the Turkish city of Şanlıurfa, in late 2018.38 Turkey has adjusted the SIG’s curriculum to remove “politically sensitive” phrases, changing things like “Ottoman occupation” to “Ottoman rule."39 In September 2017, Ali Riza Altunel, director of the “Lifelong Learning” program at the Turkish Ministry of Education, said that “the ministry is trying to transfer the Turkish education experience, especially the e-learning system,” to the approximately 500 schools serving 150,000 student in ES.40

As mentioned earlier, Turkey began addressing the dearth of medical services in ES almost immediately after the offensive began. Since then, the government has repaired hospitals, and built new ones.41 These new hospitals appear to be under the supervision and management of Turkey’s Ministry of Health. UNICEF and the World Health Organization also provide support for the medical sector in ES, specifically with providing vaccines to the region’s various vaccination centers.42

The extent to which Turkey runs ES schools and hospitals is hotly debated. A high-ranking Turkish official told this author that the teachers and doctors are all local Syrians or refugees who wished to return to north Aleppo. However, all of the Syrians work under the supervision of “Turkish advisors” staffed from the relevant Turkish ministry. This includes Turkish doctors, teachers, police, and jandarma (gendarmes). These advisors work in ES in three-month shifts. Furthermore, AFAD controls all NGO activity in the IDP camps as well. According to the director of one Syrian NGO, before any projects can be carried out in the camps, the NGO must first get the approval of AFAD.43

This leads to the broader issue of the multi-faced nature of authority in ES. As the director explained to this author, “There is no one-size-fits-all approach."44 Work in the camps requires approval from AFAD, while work in the towns requires coordination with the local councils. However, the level of coordination is limited to simply signing a memorandum of understanding between the NGO and local council for the NGO to acquire the necessary land — which it pays no rent on. Finally, any education or health related work requires the approval of the respective Turkish ministries.45

NGOs then hire locals to staff their projects, and neither the NGO, nor Turkey is involved in training for technical projects. Instead, they rely on the plethora of career engineers who worked in the water or electrical field before the war. Lastly, these projects default to the national Syrian regulations unless otherwise specified by the donor or NGO. For example, a new sewer line would be built according to the Syrian code unless the donor’s requirements for the project were stricter, in which case those standards would be used.

In an interview with a high-ranking Turkish official, the official was clear that “there are no instructions from Ankara.” Instead, action is taken solely on the initiative of local Turkish mayors and vice governors of the bordering provinces. It is these mid-ranking, but local, Turkish officials that coordinate everything; they work directly with AFAD and the local councils, with the various ministries active in ES, and even with the Turkish military units and MIT officials deployed in the region.

Anonymous, Interview with author, Gaziantep, Turkey, January 9, 2019.

Left, refugees of the Syrian Civil War. (Photo by Ensar Ozdemir/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

The role of the Turkish government

The Turkish government’s role in ES is highly complex. As already discussed, Turkish institutions like AFAD, the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Education, and the Jandarma are all on the ground in north Aleppo either supervising or training their Syrian counterparts. In this regard, Turkey has neither fully coopted, nor fully supports Syrian government institutions in the region. Syrian institutions appear to have at least some minimal say in their futures and the actions of the Turkish government, meaning at most there is a covert cooption of Syrian institutions. But in other fields, particularly reconstruction and local councils, the Turks appear to play only a minor supporting role, providing the minimal necessary funding for these institutions to continue operating while pushing both Syrian and Turkish businesses to carry out the bulk of reconstruction activities.

One area that exemplifies this dual track of co-option and support is the “Police and National Security Forces,” also known as the FSP. As with Syrian teachers and doctors in ES, police were recruited both from refugees within Turkey and among locals in north Aleppo. Police recruits undergo five weeks of training in Turkey run by the Turkish police and Jandarma — and receive their weapons, uniforms, and salaries from the Turkish government.46 According to the head of the FSP, Turkey also provides significant logistical support for the group.47 This degree of support makes sense, as Turkish soldiers and officials from the National Intelligence Organization (MIT) are deployed across ES, along with the Turkish civil servants working in the civilian sector. Protecting these Turkish citizens from both ISIS and People’s Protection Units (YPG) or Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) attacks would be a priority for the Turkish government. Training and supporting the local security forces in ES goes a long way toward ensuring that protection.

However, there are some cases in which Turkey has pursued a policy of covert co-option. As detailed in the previous section, Turkish support for ES schools comes with a cost. School curriculums must be adjusted to meet the demands of the Turkish Ministry of Education. Furthermore, NGOs that wish to implement education or health projects must first receive approval from the Ministry of Education or Ministry of Health.48 Likewise, AFAD maintains official control over IDP camps in ES, although it does not appear to block the activities of Syrian NGOs.

Finally, it seems that Turkey is able and willing to exert some degree of control over the decision making and composition of local councils. In Tamimi’s interview with the former member of Ehtemlat’s local council, the man stated that the council was disbanded “by a decision of the Turks. … They say that the order was Turkish, but the order was managed by military personnel [i.e. rebels], and the Turks did not intervene.” The interviewee seems to claim that unknown Turkish officials ordered the disbanding of Ehtemlat’s council and had a Syrian opposition faction carry out these orders. He goes on to claim that the “central council,” or area directorate, is partially staffed with Turks and works directly with Turkey. Thus, while the Turkish government’s support for local councils appears to be limited to paying salaries, there is at least one instance in which officials have not shied away from overt intervention in the local councils’ day-to-day activities.

None of this explains the relationship between the ES region and Ankara, however. It is one thing for ministries and aid organizations to work to varying degrees within the region, but to truly understand north Aleppo’s role in the eyes of the Turkish central government requires understanding Ankara’s involvement with civil society and local governance. Simply put, there isn’t any.

In an interview with a high-ranking Turkish official, the official was clear that “there are no instructions from Ankara.” Instead, action is taken solely on the initiative of local Turkish mayors and vice governors of the bordering provinces. It is these mid-ranking, but local, Turkish officials that coordinate everything; they work directly with AFAD and the local councils, with the various ministries active in ES, and even with the Turkish military units and MIT officials deployed in the region.49

The interviewee explained the structure as follows: The mayor of a Turkish border town communicates directly between the local council in Syria and the vice governor of the Turkish province. The vice governor passes on that information to the governor, but can and does also communicate directly with the Syrian local councils. Thus, the vice governors of Kilis and Gaziantep provinces have become the key interlocutors for Turkish aid to Syria. The local councils of Jarabulus, Azaz, and Akhtarin work directly with the vice governor of Kilis while the local councils of al-Rai and al-Bab work directly with the vice governor of Gaziantep.50

For example, according to the pro-government think tank SETA, it is the Gaziantep Metropolitan Municipality that has “provided basic needs” to Jarabulus, including “dump tractors … waste collection trucks … 600 garbage dumpsters; providing heavy duty vehicles, such as Leopard and bulldozers; building 138 lavatories; supplying sanitary packages; and various vehicles for possible disasters."51 This represents a significant aid package to the Jarabulus district and yet all of it came directly from the Gaziantep municipality, not the central government or Turkish federal agencies, reinforcing the claim that neither orders, nor funds come from Ankara.

Conclusion

As has been made clear above, Turkey's central government does not play any significant role in Turkey’s activities in north Aleppo. It was the mayor of Gaziantep who first visited ES and offered assistance and services. It was the Gaziantep Chamber of Commerce, not Ankara, that determined when the Karkamış border crossing would reopen, and it is Kilis that mediated between Azaz and ET Energy — just to name a few examples. The only federal presence comes in the form of Turkish agencies: AFAD, the Ministry of Health, and the Ministry of Education. Yet even these organizations coordinate with the local vice mayors, not Ankara.

However, this does not mean that Turkey is not invested in north Aleppo. The integration of Turkish telecoms companies and service providers across the region creates a huge anchor for the government. What would happen to these deals — many of which extend for the next decade — were this region to return to the control of Damascus? Without a doubt the Syrian counterparts of these companies, such as SyriaTel, owned by relatives of Bashar al-Assad, would take over. However, the economic benefits of north Aleppo for Turkish businesses seems too great for Ankara to simply hand the area over to the Assad regime.

Thus, the current state of local governance in the ES region is as follows: Local councils must coordinate with I-NGOs for some of their service needs, rely on Syrian and Turkish businesses for reconstruction contracts, and always remain in line with the Turks, whose respective ministries must approve everything. The crucial piece of this multi-layered structure is the fact that Ankara has offered neither significant funds, nor direction for the region, meaning there is no clear long-term vision and the aid provided to each council is dependent on that council’s relationship with its Turkish mayor or vice governor counterpart. Yet, seemingly in contradiction to this apparent disinterest from Ankara is the fact that huge amounts of industrial investment has poured in to both southern Turkey and north Aleppo and clear long-term economic ties have been forged. So, while Ankara may wish to ignore the fate of ES, the local governance structures and economy of the area have been inexorably tied to Turkey.

About the author

Gregory Waters received his B.A. with Honors in Political Economy and Foreign Policy in the Middle East from the University of California, Berkeley, in 2016. Since then he has researched and written about the Syrian civil war and extremist groups, primarily utilizing Syrian community Facebook pages for his projects. His past work has involved tracking combat death in Syria. He works as a research consultant at the Counter Extremism Project, has previously been published by Bellingcat and openDemocracy, and currently writes about Syria for the International Review.

About the Middle East Institute

The Middle East Institute is a center of knowledge dedicated to narrowing divides between the peoples of the Middle East and the United States. With over 70 years’ experience, MEI has established itself as a credible, non-partisan source of insight and policy analysis on all matters concerning the Middle East. MEI is distinguished by its holistic approach to the region and its deep understanding of the Middle East’s political, economic and cultural contexts. Through the collaborative work of its three centers — Policy & Research, Arts & Culture and Education — MEI provides current and future leaders with the resources necessary to build a future of mutual understanding.

Endnotes

1. Centralization and Decentralization in Syria: Concepts and Practices, Omran Center for Strategic Studies, November 12, 2018.

2. The Political Role of Local Councils in Syria - Survey results, Omran Centre for Strategic Studies, July 1, 2016.

3. The Indicator of Needs for the Local Councils of Syria: LACU report, Norwegian People’s Aid Organization (NPA), October 2015;

Alexander Starritt,“Syria’s local councils, not Assad, are the answer to Isis,” The Guardian (London), December 14, 2015.

4. “The Indicator of Needs.”

5. “Legislative Decree 107 of 2011 Local Administration Law,” Syrian Parliament, August 23, 2011;

Samer Araabi, “Syria’s Decentralization Roadmap,” Carnegie, March 23, 2017.

6. Agnes Favier, Inside Wars: Local Dynamics of Conflicts in Syria and Libya, European University Institute (Italy): 2016;

Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi, “Reconciliations: The Case of al-Sanamayn in North Deraa,” Syria Comment, April 27, 2017.

7. Centralization and Decentralization in Syria: Concepts and Practices, Omran Center for Strategic Studies, November 12, 2018.

8. Ibid.

9. Aybike Eroğlu, “Cerablus’a su müjdesi,” Yeni Safak, September 10, 2016.

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid.

13. “بالصور .. أول مسؤول تركي رسمي يزور مدينة سورية منذ 2011,” Orient News, September 8, 2016.

14. Anonymous, Interview with Author, Gaziantep, Turkey, January 7, 2019.

15. “The Economic Impact of Reactivating Jarabulus Border Crossing Commercially,” Enab Baladi, July 4, 2018.

16. The White Helmets, Twitter Post, June 2, 2018, 8:42 am.

17. “Aleppo - The suffering of the people of Manbij increases with the rise in fuel prices and monopoly by traders,” Watan FM, December 6, 2018.

18. Wim Zwijnenburg, Twitter post, February 21, 2019, 9:57 a.m.

19. Ibid.

20. “Private Turkish Companies Impose Themselves on Northern Aleppo,” Enab Baladi, May 4, 2018.

21. Investigation Team, “From Afrin to Jarabulus: A small replica of Turkey in the north,” Enab Baladi, August 29, 2018.

22. “Private Turkish Companies.”

23. Investigation Team, “From Afrin to Jarabulus”; “Private Turkish Companies.”

24. Mohammed, Interview with Author, Gaziantep, Turkey, January 8, 2019.

25. “Private Turkish Companies.”

26. Ibid.

27. Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi, “The Local Council in Azaz: Interview,” Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi's Blog, March 10, 2019.

28. Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi, “The Local Council in Ehtemlat: Interview,” Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi's Blog, March 19, 2019.

29. Ibid.

30. Investigation Team, “From Afrin to Jarabulus.”

31. Ibid.

32. Ibid.

33. “Private Turkish Companies.”

34. Ibid.

35. Mohammed, Interview with Author, Gaziantep, Turkey, January 8, 2019.

36. Ibid.

37. From the Education office of Jarabulus and its countryside Facebook page,

.مكتب التربية والتعليم في جرابلس وريفها

38. Investigation Team, “From Afrin to Jarabulus.”

39. Ibid.

40. Ibid.

41. Ibid.

42. Obaidi al-Nabwani, “Civil council opens center for routine vaccinations in al-Rai, Aleppo,” SMART News Agency, December 10, 2018.

43. Anonymous, Interview with Author, Gaziantep, Turkey, January 7, 2019.

44. Ibid.

45. Ibid.

46. Robert Postings, “Free Syria Police: Creating Security and Stability in North Aleppo,” International Review, February 7, 2018.

47. Ibid.

48. Anonymous, Interview with Author, Gaziantep, Turkey, January 7, 2019.

49. Anonymous, Interview with Author, Gaziantep, Turkey, January 9, 2019.

50. This organization structure comes from an interview with a Syrian NGO. However, it is the opinion of this author that the interviewee misspoke and meant to say that Jarabulus works with Gaziantep while al-Rai works with Kilis.

51. Özçelik, Seren and Yeşiltaş, Operation Euphrates Shield: Implementation And Lessons Learned, SETA, November 2017.