Introduction

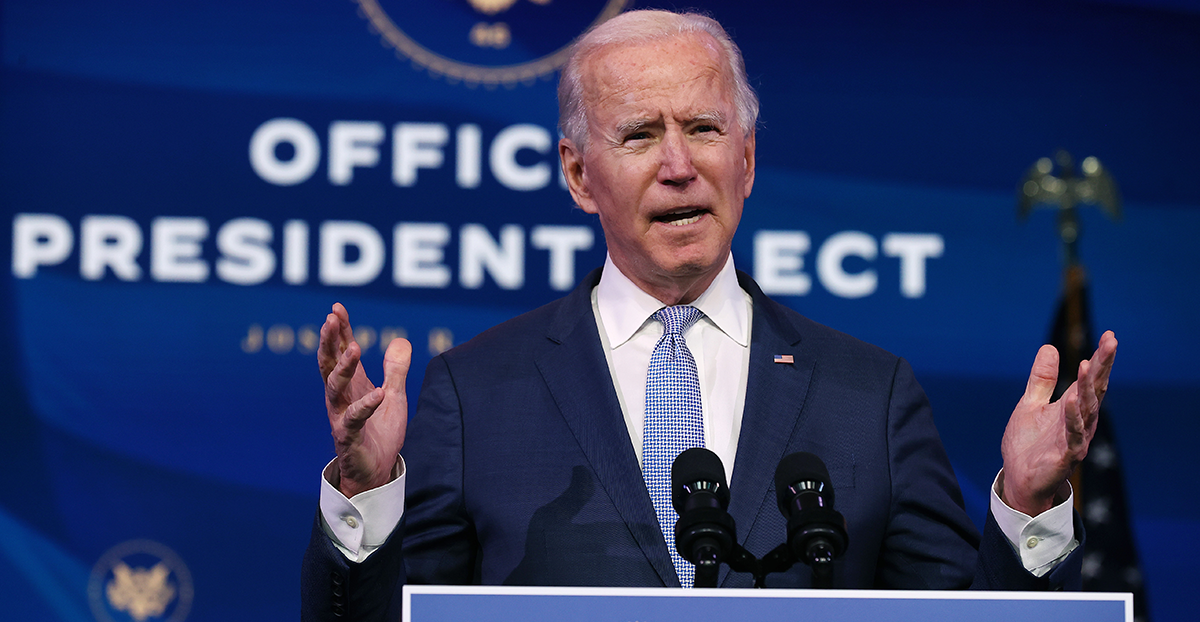

The Biden administration will face a number of major challenges in the Middle East over the next four years, from great power competition and climate change to cybersecurity and refugees and migration. But what realistically can it achieve in that time on the policy front? To better understand what's possible, we asked 10 experts from across MEI to weigh in with their thoughts.

This publication is part of MEI's series on the Biden Transition.

Viewpoints

-

Joseph L. Votel

Joseph L. Votel

Great power competition and the new administration

Many who follow U.S. national security policy can agree that the threat of China overtaking American economic, military, informational, and political leadership and influence is our greatest external security challenge. Maintaining our competitive advantage against China is the overriding concept in the 2018 National Defense Strategy, and I anticipate that this will continue into the new administration. Implementation of this strategy under the current administration has suffered from a series of missteps. These include a desire to go it alone, characterized by malignment of partners and allies, and a general lack of coherence with the overall approach.

To succeed in great power competition in the Middle East, the new administration will need to avoid making the missteps above while also articulating clear strategies and policies to preserve our long-standing interests in the region. Several realistic goals will help maintain the position of leadership and influence in this region that will support our overall desire for competitive advantage.

First, we must review and clearly articulate our enduring interests in the region. While all of the same general areas of concern — terrorism, resources, instability, and weapons of mass destruction — remain, they do so at different levels of urgency and intensity. When this review is complete, we must then develop a regional strategy that clarifies that maintaining a position of influence in the region contributes to sustaining our competitive advantage. The American people and our partners should clearly understand our long-term interests and strategy in the area.

Second, we must ensure that our military efforts in the region do not eclipse our other elements of national power. Going forward, our approach should be more about “soft power” and less about “hard power.” As a first step, every country in this region should have a confirmed ambassador, and they should be backed up by a resourced and capable regional bureau in the Department of State. Bringing to bear all national power elements in this region will be vital for prevailing against an aggressive “soft power” campaign by China. It also means ending the “endless wars” and moving toward a diplomatic communication channel with Iran to promote dialogue and contribute to a sustained lessening of tensions.

Finally, we must make every effort to rebuild relationships and partnerships in the region. Our list of friends, partners, and allies must always exceed that of China by a wide margin. The majority of countries in the region and those outside the area who maintain interests there are aligned with the United States. Relationships and partnerships must be the cornerstone of our overall strategic approach. We should not turn blind eyes to corruption and the other underlying tensions in the region, but we must stay engaged and keep our interests and the imperative for competitive advantage at the forefront of our efforts.

To preserve our place in the global order and support our vital interests, we must compete in this region. The new administration will be successful if it can pursue a sustained strategy to accomplish this objective.

Gen. (ret.) Joseph Votel is a distinguished senior fellow on national security at MEI. He retired as a four-star general in the U.S. Army after a nearly 40-year career, during which he held a variety of commands in positions of leadership, including most recently as commander of CENTCOM from March 2016 to March 2019.

-

Charles W. Dunne

Charles W. Dunne

The US needs to make human rights central to its Middle East policy

The bold protests that swept the Middle East in 2019-20 demonstrated that the demands that fueled the Arab Spring 10 years ago — for social justice, human rights, an end to corruption, and basic political freedoms — never went away. As the basic compact between ruler and ruled shows every sign of fracturing, the growing threat to regional stability will pose a major challenge for President Joe Biden.

The incoming administration is likely to be more proactive regarding human rights in the region, one area where it has suggested a sharp break with Trump policies. Biden himself has indicated there will no longer be a blank check for Egypt and Saudi Arabia, which have cracked down harshly on political opposition and civil society with the quiet acquiescence and sometimes outright support of Biden’s predecessor. Saudi Arabia literally got away with murder (that of Jamal Khashoggi) as Trump fought off any effort by Congress to hold its crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, accountable.

But Egypt and Saudi Arabia are not the only countries in the Middle East due for additional scrutiny in the context of a more energetic and holistic approach to human rights, one that pays attention to the records and practices of American allies, not just its foes. The advancing authoritarianism of Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Turkey, for example, cannot be ignored. Nor can Israel’s troubling record in the Palestinian territories and its discriminatory policies against Palestinians in Israel. And, despite the president-elect’s interest in rejoining the nuclear deal and possibly putting U.S. relations with Iran on a new footing, the Biden administration must press Tehran hard on its violent repression of its citizens, especially its appalling record of executions.

The Biden team can make an early impact by conducting zero-based reviews of U.S. political-military relationships in the region, starting with Egypt and Saudi Arabia, and work with Congress to curb out-of-control arms sales to these countries pending human rights improvements. The administration should enforce the Leahy Law, which prohibits the State and Defense Departments from providing assistance to foreign military units credibly accused of gross violations of human rights. The United States should work through the U.N. (in particular, by rejoining the U.N. Human Rights Council) and with EU partners to implement a human rights agenda and rational arms sales policies in the Middle East. The new administration could expand democracy and governance programming in the region, which the Trump administration sought to cut, as well as the role and funding of Millennium Challenge Corporation programs to encourage good governance. Most important, the administration must bring to bear the full power of public and private diplomacy, by all agencies of government, to highlight the importance of human rights, hold abusers to account, and support human rights defenders and civil society.

The new administration’s first order or business, however, must be restoring U.S. democracy and the rule of law. The events of Jan. 6 at the United States Capitol underscored the apparent fragility of America’s democratic system, enabling dictators and despots to scoff at the alleged U.S. commitment to human rights and democratic governance. Biden has pledged to host a Summit for Democracy during his first year in office to “strengthen our democratic institutions, honestly confront nations that are backsliding, and forge a common agenda.” While this will be useful primarily in confronting authoritarian challenges from Russia and China, it may also help lay the foundation for the hard work to come in the Middle East.

Charles W. Dunne is a non-resident scholar with MEI, an adjunct professor at George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs, and a non-resident fellow at the Arab Center Washington D.C.

-

Shahrokh Fardoust

Shahrokh Fardoust

Helping to improve the region’s economic prospects

The Biden administration is widely expected to focus on pressing domestic concerns, like mass vaccination, unemployment, and poverty, but the president-elect is keenly aware that governments around world, including in the Middle East, are facing similar challenges. While his foreign policy is expected to be based on traditional U.S. values, he is likely to use U.S. financial and technical support for developing countries more strategically, as a key pillar of his foreign policy, as opposed to his predecessor’s seemingly chaotic approach.

Middle Eastern governments are currently grappling with the aftereffects of the pandemic on their economies. Although the rich oil exporters have been more resilient than the rest of the region, they too have faced tightened fiscal and financial conditions, leading to sharp reductions in trade, remittances, and financial flows that have severely affected lower-income countries in the region.

The macroeconomic situation in MENA deteriorated sharply during 2020, as the region was hit by two massive and reinforcing shocks. In addition to the pandemic, the region faced simultaneous demand and supply shocks, severely affecting trade and financial flows, causing oil prices to plunge, and triggering major disruptions in domestic production of goods and services. The job-rich manufacturing, tourism, and hospitality sectors, as well as the informal sector, have been particularly hard hit.

According to the World Bank, income per capita in MENA is estimated to have contracted by 6.5 percent in 2020. Poor performance is nothing new as the region has been suffering from low growth and rising poverty and unemployment for a decade. The Arab Spring uprisings of 2010-11 were only the most dramatic expression of a century-long trend of individuals seeking to become active citizens and play their part in shaping stable societies and modern states. In their aftermath, however, the region has experienced a period of low growth and rising youth unemployment, with some two-thirds of citizens considered either poor or vulnerable.

In Yemen, violent conflict has entered its sixth year and the country continues to face an unprecedented humanitarian, social, and economic crisis, now aggravated by COVID-19. The Libyan economy has been hit by multiple shocks, including an intensifying conflict and the pandemic, underscoring the urgent need for a political solution. Iraq’s economy has contracted in 2020 due to lower oil prices, COVID-19, and political instability, and it faces rapidly rising fiscal and current account deficits. In the Palestinian Territories, economic activity has been affected by coronavirus lockdowns and has not stabilized. The fiscal position has worsened due to the pandemic and the political standoff that has disrupted the flow of revenues and aid.

Lebanon’s economy has been in free fall, losing nearly a third of its national income since 2018. A financial crisis, resulting from a banking, debt, and exchange rate crisis, has worsened as result of the pandemic, leading to political instability. The conflict in Syria, which has entered its tenth year, has inflicted massive devastation: over 400,000 are dead, millions injured, more than half the country’s pre-conflict population has been displaced, and its economy has contracted by 60 percent.

Given the magnitude of economic fallout from COVID-19, oil importers, such as Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, and Tunisia, have announced fiscal stimulus packages with increased spending on health and social safety nets, financed in part by greater international debt issuance. The scope for fiscal support, however, has been limited by high government debt (Egypt, Tunisia). An unexpectedly sharp tightening of financing conditions would put further strain on already-elevated government debt burdens.

In Iran, the unilateral U.S. withdrawal from the nuclear deal and the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” campaign have led to a more than 15 percent drop in per capita income, a quadrupling of inflation, and a sharp rise in poverty. Combined with devastating losses from COVID-19, this is likely to create a humanitarian crisis if not addressed urgently.

Further resurgence of COVID-19 or delayed vaccination rollouts are significant risks for all countries in the region. The outbreak’s socioeconomic consequences, including rising joblessness, food insecurity, and poverty, and their potential impact on political instability constitute a major downside risk.

The Biden administration is well placed to take the lead in assisting MENA countries to improve their economic prospects. Dealing with the following issues is likely reduce tensions, mitigate some of the downside risks, and have positive economic spillover effects:

- Assisting with an effective vaccination rollout;

- Working with international financial institutions and the G20 to provide financial assistance, debt service suspension, and relief to highly indebted countries;

- Restoring aid to the Palestinian Territories and encouraging resumption of economic and political dialogue between the Palestinian Authority and Israel;

- Helping ease economic tensions between Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE;

- Helping to bring an end to the Yemen war;

- Opening up pathways to ease tensions with Iran and revive the nuclear deal;

- Encouraging trade and investment within the region and with the rest of the world;

- Assisting countries in preparing to deal with climate change and take advantage of digitalization and other new technologies;

- Initiating strategic and multilateral dialogue on Syria’s future and refugee return.

Shahrokh Fardoust is a research professor at the Global Research Institute, College of William and Mary, and a non-resident scholar at MEI.

-

Charles Lister

Charles Lister

Strategic success in counterterrorism will require a long-term, multilateral approach

Although foreign policy attention is likely to prioritize challenges posed by great power competition, a Biden administration will come into office on Jan. 20 amid an unprecedently diverse range of terrorist threats. In the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia, these threats are greater in number, more diverse in scope, and more potentially potent in terms of intent than at any point since 9/11. Over the last 20 years, al-Qaeda and then ISIS have grown into global movements, with increasingly expansive networks and a proven capacity to grow locally and destabilize both regionally and internationally.

Notwithstanding the clearly increased threat posed by domestic far-right terrorism, the U.S. is arguably safer from a 9/11-style jihadist attack than at any time in recent history. While securing the homeland from large-scale foreign-directed terror attacks should be considered a counterterrorism victory, the U.S. is not impregnable, as the November 2019 attack in Pensacola, Florida demonstrated. Likewise, the risk of foreign-inspired attacks remains ever present.

Of equal importance is the often-ignored truth that securing the homeland represents only half of the counterterrorism challenge. On the one hand, some jihadist groups, including some in Syria, Somalia, and North Africa, remain determined to plot significant external attacks. On the other hand, theaters of civil conflict and ungoverned spaces have proliferated markedly across the globe. This trend, particularly post-Arab Spring, has been a boon to both al-Qaeda and ISIS across swathes of the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia and has catalyzed a strategic shift toward prioritizing localism. In doing so, many groups are growing deep and sustainable roots, and in many cases achieving a semblance of local credibility vis-à-vis failing or failed state governance. Some are even seeking to compete in local or national politics.

Protecting the homeland while letting pockets of the developing world fall irretrievably into terrorists’ hands guarantees far greater problems down the line. President-elect Biden’s “Counterterrorism Plus” strategy is the ideal antidote to today’s prevailing trends. Going forward, the U.S. needs to learn from the recent anti-ISIS campaign in Syria and Iraq, where a light footprint approach fronted by special operations forces and focused on enhancing the ability of allied local partners in their local fight against terrorists was met with success.

Critically though, that success has until now been tactical in nature. ISIS’s territorial caliphate may be gone, but it remains operationally active in over a dozen countries and is showing signs of a slow resurgence in its Syrian and Iraqi heartland. Strategic success requires time and an investment not just in targeted counterterrorism actions, but in long-term capacity building and broader multilateral efforts in humanitarian relief, supporting stabilization and reconstruction, and improving state-level governance. Ideology may be important to terrorism, but it’s not its lifeblood — that role is played by deeper socio-political and economic issues, which require consistent and sustainable attention not just from the U.S., but the international community at large. With the Biden administration's emphasis on reviving multilateralism, alliances, and diplomacy, it should be well placed to pursue such a strategy.

Charles Lister is a senior fellow and the director of the Syria and Countering Terrorism and Extremism Programs at MEI.

-

Sarah El Battouty

Sarah El Battouty

An opportunity for partnership in the fight against climate change

After the tumultuous presidency of Donald Trump, the next four years under Joe Biden will usher in a number of policy changes on the social and economic fronts. Such policies can be described as reparative, especially when it comes to climate action. Under the Trump administration there was a strong pushback on America’s environmental focus — concerns were dismissed, public outcry ignored, and investments in climate change and environmental research and protection were scaled back or ended altogether. The withdrawal of the U.S. from the ambitious Paris Climate Agreement was a clear sign of where the administration stood on the issue.

President-elect Biden has said his administration will take a very different approach to climate change, announcing plans to invest in each of the sectors that contribute and structuring his cabinet and allocating budgeting to support this. However, in light of the recent social unrest and mounting domestic crisis in the U.S., it will be challenging for the incoming government to allocate the massive amounts required and take immediate action on the issue. Ultimately, it is the domestic politics of climate change in the U.S. that will define how America positions itself in the global fight for climate mitigation and adaptation.

Efforts to shift to a carbon-neutral economy, create jobs, and set up partnerships will need to start immediately. President Biden will have to rebuild trust that the United States will recognize its position as both a leading global contributor to emissions as well as a global solution partner to reduce further negative environmental impact. This relationship is not beyond repair, but the scientific community and climate-vulnerable groups have been ignored often enough by leaders in the White House to question the next administration’s ability to commit given the country’s serious domestic issues and internal unrest.

The United States government has politicized climate change and made it a partisan campaign issue, and this is a real problem. In doing so the magnitude and incremental effects of climate change on humanity have been reduced to a political fight. Somehow — and fast — the new administration will have to distance itself from the partisan fight over climate change, make clear it understands the seriousness of the crisis, and then begin an era of changing legislation and creating frameworks and partnerships to address the issue.

The MENA region is considered vulnerable to climate stresses that vary in severity yet continuously affect both societies and economies. Water scarcity, extreme heat, rising energy prices, and food insecurity will all change the MENA landscape, and with respect to America’s renewed commitment, this can also become an opportunity to create a new bilateral partnership between the region and the U.S. The last time the Democrats were in power, the MENA region endured the unrest of the Arab Spring, and since then the impact of climate change has only increased. Climate migration in the region failed to make any headlines overseas from 2011-16 when the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals were ratified by MENA states and sustainable development strategies like Vision 2030 began to be formulated.

President Biden will step into office with a new opportunity to take responsibility for climate change. His administration will also be dealing with a different MENA region, one that is increasingly aware and committed to action to save themselves and their resources and be part of a global fight against climate change. With the right guidance, President Biden can forge a new pathway with countries in the region to broker peace, resolve issues, and invest to create jobs. Understanding the MENA region, and its challenges, geographic needs, and demographics, will require a systemic and future-oriented approach. As difficult as it sounds, climate action between the U.S. and MENA will need to transcend politics — a challenging and under-rehearsed endeavour. Nevertheless, the planet’s condition is deteriorating rapidly and the results are already crippling governments. Leadership in this field will require creating new paradigms. In light of the coronavirus pandemic, seizing the opportunity to unite humanity to resolve a common global crisis is no longer merely a poetic sentiment. The lesson that can be taken from this is that climate change is an urgent global challenge, one that cannot be fought alone, nor one that will present a clear winner in the end. It is quite simply bigger and more important than politics.

Sarah El Battouty is a non-resident scholar at MEI, an award-winning architect with 18 years’ experience in the field of green and environmental building, and the founder of one of Egypt’s leading environmental design and auditing companies, ECOnsult.

-

Ross Harrison

Ross Harrison

Less will be more for the U.S. when it comes to the Iran-Saudi rivalry

The Middle East diplomatic landscape has been rife with ambitious U.S.- sponsored peace initiatives. Some were successful and enduring, like the 1978 Camp David Accords between Egypt and Israel. There have also been many more notable failed attempts, such as the stalled talks between Israelis and Palestinians during the Obama administration.

Diplomacy, however, does not have to be big and bold to be successful. The Biden administration has an opportunity to help stabilize the Middle East with more subtle diplomacy by disentangling the U.S. from the regional rivalry between Iran and Saudi Arabia. This has the prospects of reducing the temperature of relations between these two regional rivals and possibly even prompting them to settle some of their differences on behalf of regional stability.

Here is why this is a constructive way forward. Like it or not, the United States has become party to the rivalry between Iran and Saudi Arabia. Of course there are profound issues related to wars in Syria and Yemen and instability in Iraq and Lebanon that separate them. But much of the enmity they harbor for each other relates in no small way to Washington. Iran sees Saudi Arabia (and Israel) as the tip of the spear of U.S. efforts to undermine it. Iran sponsored attacks on Saudi oil facilities in 2019 after Washington’s maximum pressure campaign is prima facie evidence of this. Saudi Arabia has felt little incentive to even entertain diplomacy with Iran given the large U.S. military footprint in the Persian Gulf and Trump’s hostility toward Iran. Not only is the United States a party to the Iran-Saudi rivalry, but it has hardened the resolve of both sides, driving them further away from diplomacy, with negative consequences for the entire region.

The United States lacks the capacity to cajole either of the regional rivals toward rapprochement. But Washington can play a constructive role by extricating itself from the role of protagonist in this conflict. This will require recalibrating relations with Saudi Arabia, supporting Riyadh but also making sure that it does not continue using Washington as a crutch for eschewing diplomacy. It also necessitates the United States working to ensure that the Abraham Accords between Israel and the UAE are used as a bridge for building further regional cooperation and not merely as a cudgel for deepening hostilities to Iran. And it will necessitate the United States moving toward a diplomatic track with Iran, starting with rejoining the 2015 nuclear deal, on the condition that Tehran reverts to compliance. The U.S. will need to use leverage to move an intransigent Iran into a more constructive regional role, but skillful diplomacy can deprive Iranian leaders of the narrative that their regional adventurism is a necessary defensive crouch for deterring a hostile Washington.

Disentangling the United States from the regional rivalry between Iran and Saudi Arabia won’t ensure peace between the two regional powers. But it can force Iran and Saudi Arabia to deal with each other on their own terms, and not hide behind relations with Washington. If successful in cooling the temperature of relations between these two powers, it can also possibly have other benefits, such as sucking some of the oxygen out of the proxy conflict dimension of the civil wars roiling Syria and Yemen and helping stabilize Lebanon and Iraq.

While the United States can’t start a peace process between Iran and Saudi Arabia, peace should be the objective of U.S. diplomacy. Rebalancing relations with friends and foes would go a long way toward this objective. Steady resolve rather than bold diplomacy might be just what the region needs from Washington right now.

Ross Harrison is a senior fellow and director of research at MEI.

-

Dalal Yassine

Dalal Yassine

Reversing Trump’s policies on immigration, refugees, and asylum-seekers

On Jan. 8, President-elect Joe Biden committed to keeping his campaign promises. He said that he will introduce an immigration bill "immediately” and rescind President Donald Trump’s executive orders. This is welcome news and it is important that the Biden administration reverses Trump’s policies targeting refugees as one of its early actions. There are four major steps that President Biden needs to take.

President Trump adopted a hardline stance on issues related to immigration and asylum. The most recent was his Dec. 31 announcement extending the ban on entry of immigrants and nonimmigrants into the United States until March 31, 2021. This order was originally imposed last April due to the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. Although there has been a COVID-19 resurgence in the United States and globally, it is only a pretext for Trump’s harsh policies toward refugees and immigrants.

Among President Biden’s first acts should be rescinding Trump’s travel ban. The ban prohibited citizens from seven countries as well as Syrian refugees from entering the United States. It also facilitated the removal of refugees already settled in the United States to their countries of origin, even in cases where it posed a threat to their lives. Revoking the ban will demonstrate that President Biden truly intends a return to normalcy as he has promised.

Trump’s antagonism toward refugees did not end with the travel ban. His administration impeded the U.S.’s refugee resettlement program, created in 1980. Since 2017, roughly 118,000 individuals were approved for resettlement, fewer than half of which were from the Middle East. Biden promised to raise the annual ceiling for refugees to 125,000 and doing so will send a clear message. Even more important will be ensuring that the annual minimum of 95,000 refugees are settled in his first year in office and an increasing number in the following years, and that they are provided with the necessary support for their new lives in the United States. Priority should be given to reuniting refugees that have already settled in the U.S. with their family members.

The Trump administration also adopted policies to deter individuals from seeking asylum in the United States. These policies are in violation of international law and America’s responsibilities to provide safe haven to those at risk. It is imperative that the Biden administration reverse these detrimental policies as soon as possible.

Finally, as COVID-19 continues to claim lives around the globe, the Biden administration must aid the increasing number of forcibly displaced people. This includes resuming U.S. support for the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNWRA) and increasing funding for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Combined, UNRWA and UNHCR are responsible for over 26 million refugees in the Middle East and worldwide. As the U.N. agency responsible for Palestinian refugees, UNRWA provides essential health and education services to 5.7 million Palestinian refugees. The United States was the largest contributor to UNRWA before the Trump administration cut off funding in 2018.

In addition, the Trump administration pressured leading Arab states to eliminate their support for the agency as well, and UNRWA has faced a budgetary crisis as a result. Refugees are facing a difficult winter in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, living in overcrowded camps with poor infrastructure. It is vital that the Biden administration provide support to the organizations that can best assist refugees.

President Biden has an opportunity to repair the damage done over the past four years. Unlike his predecessor, Biden should provide thousands of individuals around the world fleeing persecution with the protection they deserve. Otherwise, the repercussions of Trump’s policies on immigration, asylum seekers, and refugees will be felt for years to come.

Dalal Yassine is the executive director of Middle East Voices, a lawyer and advocate for gender and human rights for Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, and a Non-resident Scholar at MEI.

-

Bilal Y. Saab

Bilal Y. Saab

Guidance for a new force posture in the Middle East

For more than four decades, America’s military presence in the Middle East has prevented hostile powers from dominating the region and controlling a large chunk of the world’s energy resources. To say that it has been a collective good, enjoyed by many but exploited by some, would be an understatement.

However, there’s no hiding the fact that this footprint has failed to pacify the region and deter a host of asymmetric threats posed by state and non-state actors alike. Even conventional assault against Saudi Arabia in more recent years CENTCOM could not stop.

Because some of Washington’s assets in the region are not well-suited to effectively deal with those growing unconventional challenges, many including myself have called for adjusting the U.S. regional posture and possibly even trimming it. That the United States might need to commit more military resources to the Indo-Pacific — the main theater of great power competition — is further reason to downsize in the Middle East.

These U.S. motives on their own, coupled with America’s reduced dependence on Middle Eastern oil, are more than enough to reconsider the size or shape of the U.S. military presence in the Middle East. But there’s another reason: America’s vast and commanding posture, for all its strategic benefits, has had the unintended effect of harming U.S.-Arab security cooperation and perhaps even slowing down the military evolution of America's Arab partners.

For the Arab partners, befriending the world’s only superpower has brought them solid protection against existential threats and though shattered sometimes, some peace of mind. But it also led to complacency and extreme dependency on Washington. It’s hard to convince the Kuwaitis, for example, to more aggressively upgrade their defenses and protect their land borders when roughly 13,000 U.S. military personnel are spread among several bases on Kuwaiti territory. Or the Bahrainis to further invest in their maritime capabilities when the U.S. Fifth Fleet and NAVCENT are headquartered in Manama. The list goes on. To be clear, I’m not arguing for ending or dramatically reducing America’s military presence in the region as a means to pressure the Arab partners to step up. That would be foolish and dangerous. But I am making the case for a strategic review of America’s military presence in the region that would go beyond acquiring the right set of military capabilities and actually integrate the vital goal of enabling stronger U.S.-Arab security cooperation.

CENTCOM’s politically attractive and strategically invaluable “by, with, and through” principle is just that — a principle. It needs to be formalized and turned into an official strategy or doctrine with clear mechanisms for implementation and sustainment. This will require Washington to pay much closer attention and allocate more human resources to defense institution building in security cooperation.

Bilal Y. Saab is a senior fellow at MEI and the founding director of the Defense and Security Program.

-

Steven Kenney

Steven Kenney

The past is not the only prologue

One of the challenges for President Joe Biden and his administration in the Middle East is one they will face in other areas as well. That challenge is looking creatively forward rather than backward — imagining the possible rather than returning to the familiar.

Biden brings nearly five decades of experience and policymaking history into the White House, much of that in foreign affairs. He also brings a strong personal philosophy of restoring approaches in government regrettably abandoned since his time in the Senate. This is part of why he was elected, and it will serve the nation and its allies in the Middle East and elsewhere well. But it will also incline him to favor familiar objectives and familiar courses for achieving them, across the board, including in foreign policy.

Many incoming members of the Biden administration, some already named and others yet to be, are also longtime veterans in their policy spheres. Like the president himself, many likely will want to return to paths they helped our government pursue in prior administrations. In some areas the aim will be to reverse more recent policies and repair what many, legitimately, see as damage done.

Looking back to past policies believed to be the right ones is exactly what the new president and his administration should do. The risk lies in making them a default starting point. The dynamics and issues in the Middle East over the next four years will not be like those of the last four years or the last decade. The challenge is to not let “policy muscle memory” impede fresh, what-if thinking.

A goal should be to inject some “futurist” thinking into its strategy for the region.

For whatever the new administration identifies as the priority issues, start by examining key assumptions. Acknowledge what those assumptions are in the first place, then challenge where they may have weaknesses. Consider what new or potential future conditions may render some of them invalid. Consider what it would look like — or could look like — if different assumptions were true.

As the president and his advisors chart the course for U.S. policy for the Middle East, part of their approach should be to start from the future and work backward to the present. What outcomes do they want to see, not only four years from now, but 10 or more years? Standing in that future and looking back, what policy actions over those years would have helped create them? Undoubtedly some will be the actions that “muscle memory” suggests, but others may be surprising. The strategy to best serve U.S. interests in the region and those of our allies there will combine both.

Steven Kenney is the founder and principal of Foresight Vector LLC, a strategy consultancy, advising public and private sector executives on how to create their organizations’ futures. He also is a non-resident fellow at MEI and leads MEI’s Strategic Foresight Initiative program.