In the corridors of power in Brussels it is common to hear that the position of the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (HR) is an impossible job. It may actually become even more difficult for the outgoing Estonian Prime Minister Kaja Kallas, who is set to succeed the Spanish Josep Borrell as the European Union’s foreign policy chief in the coming weeks.

EU treaties confer to the HR the mission of ensuring the consistency of the EU’s external action. What that means in Brussels’ jargon is that the representative is expected to find common ground between the 27 EU member states, which are the keyholders of EU foreign policy. Furthermore, the representative is to coordinate all external policies under the responsibility of the European Commission (the EU’s supranational executive body), using her/his second hat as vice president of the Commission.

Living up to the expectations of EU treaties is likely to become particularly arduous for Kallas when it comes to leading the EU’s approach vis-à-vis what the organization has called its southern neighborhood. It is not only that she will have to impose her credibility and authority in a region that is not precisely the number one foreign policy priority of her Baltic home country. It is also because her boss, the president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, announced in late July her intention to create the new portfolio of Commissioner for the Mediterranean. This institutional novelty is indeed likely to further constrain Kallas’ task and her ability to coordinate the EU’s policies in the Middle East and North Africa.

In fact, a marginalized role for the HR in the EU’s southern neighborhood would not be breaking news. It would rather be the continuation of a trend that started in 2023 under the combined effect of two phenomena. On the one hand, pressed between President von der Leyen and some EU member states reluctant to exert too much pressure on Israel, HR Borrel’s voice has been rather sidelined in the context of the war in Gaza. On the other hand, the EU’s foreign service under his command, the European External Action Service (EEAS), has been largely kept in the dark when a new generation of EU deals with countries such as Tunisia, Egypt, and Lebanon have been designed.

As much as such institutional infighting matters in Brussels’ politics, the future of the EU’s foreign policy in the region will depend on more than just the capacity of the new leadership to overcome these structural challenges and the lack of coherence that have haunted this policy since its early days. What will be even more significant is whether the EU will maintain a trend that has gained traction over the last year: an increasingly transactional engagement with its partners.

Brussels’ conversion to transactionalism is rather recent and has been progressive. Arguably, it started in 2015, when the so-called European Neighborhood Policy (ENP) partly abandoned the grand ambitions it had set for itself at its creation 10 years earlier. Faced with growing instability resulting from the Arab uprisings and in particular the war in Syria and concerned with migration flows coming from its southern neighborhood, the EU started prioritizing short-term goals over the longer-term objective of transforming its partners. In 2016, the EU signed an agreement with Turkey that would confirm this trend and arguably inaugurate a new phase in European foreign policy. The EU promised a €6 billion aid package for Syrian refugees in Turkey in exchange for Ankara’s commitment to slow down irregular migration flows and cooperation on readmissions. The legacy of this unprecedented deal materialized six years later with a series of agreements driven by the same rationale.

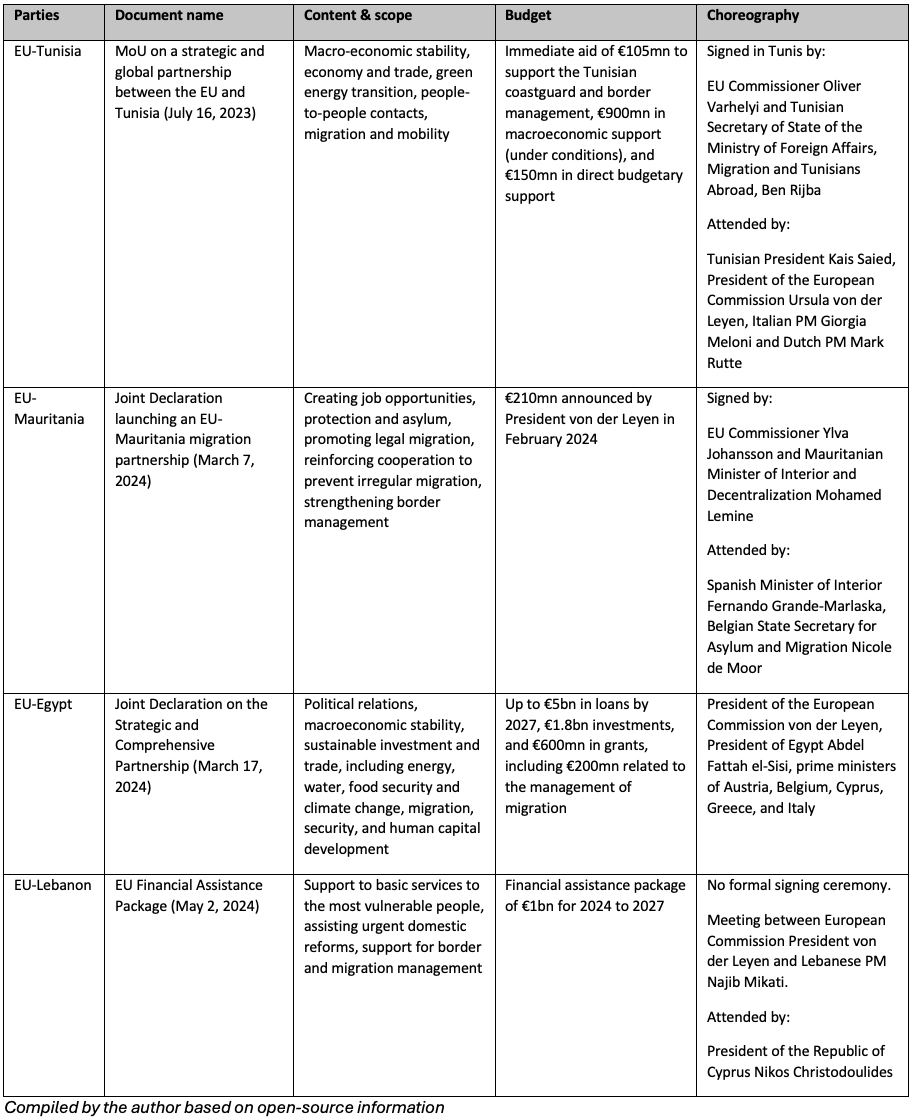

On July 16, 2023, the EU signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with Tunisia. On paper, the deal covered five main areas of cooperation: macroeconomic stability, economy and trade, green energy transition, people-to-people contacts, and migration and mobility. However, despite its packaging, there is little doubt that the EU’s main motivation in pledging €1.1 billion was to secure Tunisia’s support in limiting irregular migration flows to European shores.

On March 7, 2024, the EU signed a migration partnership with Mauritania. The EU committed €210 million to support Mauritania and its security forces in deterring people smuggling and trafficking.

Ten days later, the EU and Egypt signed a strategic and comprehensive partnership agreement. The EU committed to provide, by 2027, up to €5 billion in loans, €1.8 billion in investments, and €600 million in grants, including €200 million related to the management of migration.

On May 2, 2024, the president of the European Commission announced that the EU would provide a financial assistance package of €1 billion for 2024-2027 to Lebanon, with a focus on support for basic services, including refugees, internally displaced persons, and host communities, assisting urgent domestic reforms, and support for border and migration management, including strengthened support to the Lebanese Armed Forces

Table 1: A summary of EU-partner agreements signed in 2023 and 2024

Despite their different framing and scope, these four agreements are underpinned by the EU’s anxiety to secure its partners’ cooperation in deterring irregular migration (and by the intention of the EU’s partners to leverage this). The choreography of the visits is telling in this regard. On each of the four occasions, representatives of EU member states accompanied EU signing authorities. In fact, EU member states have been instrumental in making them happen. It is no secret that Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, eager to be seen domestically as delivering on her promise to curb irregular migration, played a major role in the deal with Tunisia. Similarly, Spain triggered the declaration with Mauritania, shortly after thousands of migrants attempted to reach the shores of the Spanish Canary Islands at the beginning of 2024. The joint visit to Lebanon of President von der Leyen and Cypriot President Nikos Christodoulides took place amid reports of increasing migration flows from Lebanon to Cyprus and of Cypriot reception capacities being overwhelmed. Lastly, Egypt is not only seen by EU member states as a destination for refugees fleeing conflicts in neighboring countries but its soaring population is also perceived as a potential threat should the domestic situation derail.

All in all, migration seems to have become the new pivot of the EU’s cooperation with its Mediterranean partners. This has happened to a large extent as a result of political circumstances. It is important to keep in mind that all these deals were sealed in the run-up to the EU general elections held in June 2024. Indeed, President von der Leyen needed to secure both the support of heads of states and governments and of her political group, the center-right European People’s Party, in order to get confirmed as president of the European Commission. The fact that Borrell, a left-wing politician, was marginalized from these deals while most of the ministers who played a part in them are from right-wing political parties seems to indicate a growing politicization of EU foreign policy. In order to get support from Italian Prime Minister Meloni, President von der Leyen went as far as to prepare the Tunisian deal in close consultation with her and without consulting other EU member states, which infuriated some EU capitals.

However, using only a political lens to understand the Tunisia MoU and the ensuing deals is not sufficient. There are good reasons to think that this new generation of agreements illustrates the beginning of a structural shift in how the EU conducts its foreign policy in the MENA region in a way that goes beyond short-term political considerations. The EU’s efforts to diversify and try out new modalities of engagement arguably come from the emerging consensus that the ENP that has framed the EU’s engagement in the region over the last 20 years is no longer fit for the purpose. There seems to be ENP fatigue both within the EU and among Europe’s southern Mediterranean partners.

When it was designed in 2004, the ENP borrowed a lot from the methodology and the transformative objectives that characterized the EU’s approach toward those countries that were bound to join the union (the so-called EU enlargement policy). As mentioned above, the EU started realizing in 2015 that the approach was not working and began upgrading the policy accordingly. It also gave a new boost to the ENP with the New Agenda for the Mediterranean (2021-2027). Despite all these efforts, the EU’s partners have continued to routinely criticize what they perceive as a bureaucratic policy and an unbalanced relationship. Many of them have unequivocally expressed that they were not interested in signing the so-called deep and comprehensive trade agreements the EU was proposing. On the EU side, ENP fatigue is also palpable. After the EU invested significant political and financial resources in the Tunisian transition under the aegis of the ENP, Tunisia’s hostile rhetoric under President Kais Saied came as a cold shower and made the EU doubt the way it had engaged in the region.

With the deals described above, the EU is arguably trying to pursue short-term interests while at the same time offering a framework of engagement that is to the liking of its partners. The EU’s partners have indeed come to the conclusion that migration provides leverage that enables them to achieve something close to the relationship of equals they have repeatedly called for over the last decade, something inconceivable in trade negotiations. Brussels’ conversion to transactionalism may therefore not be as bad as many observers have claimed. What would be problematic, however, is if Brussels were not able to expand its conversion to transactionalism beyond migration.

These recent deals are not a panacea for solving all misunderstandings in Euro-Mediterranean relations, as was evidenced by the rocky implementation of the agreement with Tunisia. It is also true that the EU cannot apply the same recipe with all countries. Algeria, for instance, is reluctant to engage in such migration deals, probably because its hydrocarbon reserves provide a strong enough position from which to negotiate. For the EU itself, turning migration into the backbone of cooperation with its partners is risky. On the one hand, the EU may become dependent and subject to migration blackmail by its partners. On the other hand, this could be counterproductive to the pursuit of other EU objectives.

Brussels’ conversion to transactionalism is not likely to be reversed anytime soon. This is not necessarily a bad outcome, as long as both shores of the Mediterranean realize that transactionalism does not end with migration and that they have a lot more to gain from inventing new cooperation formulas in other sectors as well.

Emmanuel Cohen-Hadria, a Non-Resident Scholar in MEI’s North Africa and the Sahel Program, is a policy analyst specializing in EU foreign policy, with a particular focus on the MENA region.

Photo from the EU’s Directorate General for Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.