In a bid to combat the spread of the novel COVID-19 virus, governments across the world have been scrambling to engage in mass testing, quarantines, contact tracing and eventual shutdowns. On March 24, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi took the drastic step — with just a few hours advance notice — of ordering the immediate three-week lockdown of the entire country.[1] While this measure was necessary and prudent, it brought to the fore India’s track record of poorly executing decisions that affect the whole country, especially as it stranded thousands of suddenly out-of-work migrant workers and placed marginalized communities further at risk.[2]

Amid the massive disruption caused by the pandemic, local non-government organizations (NGOs) have sprung into action to fill in the gaps of communication and delivery of essential items to underserved communitiess.

NGOs and Underserved Communities

Urban slums dot various metropolitan cities across India. According to some studies, at least one in four Indian reside in such slums.[3] Slum dwellers typically have little or no leverage in the corridors of power. They tend to lack access to adequate food, clean drinking water, sanitation, healthcare and education facilities. In extreme cases, such slums are also at the receiving end of overnight demolitions in favor of building malls or other properties that are more economically attractive.[4]

Against this backdrop, NGOs serve an important role, working to help these underserved populations. First, they help fill in the gaps that governments often neglect. Second, they create local networks and resources, often drawing from the very same pool of people they help. Third, they foster upward mobility for slum dwellers by generating jobs. Fourth, they create credibility banks that are often used during emergency situations. Fifth, those that are well-staffed and organized maintain records of the work they do, thereby providing a repository of valuable data that can later be accessed.[5]

Bangalore (officially known as Bengaluru), India’s Information Technology (IT) capital and home to more than eight million inhabitants, has over 2,000 slums.[6] More than 20 different organizations work with a range of slums and economically weaker sections of the society to provide aid, educate the young, generate employment, raise awareness on basic hygiene and represent politically. These organizations’ services came into special use during the lockdown.

Left in the Lurch

While the central government has taken some steps to prevent infections from spreading more rapidly, it has been far more difficult to reach Bangalore’s hundreds of slums and Economically Weaker Sections (EWS). This could be due either to lack of access to news media or general distrust of government initiatives, particularly among the poorest segments of society.

The sudden announcement by the central government to shut down the country for 21 days hit slum dwellers and daily workers especially hard. First, many slum dwellers do not own televisions or radios, and were therefore caught by surprise by the lockdown. Second, many day laborers were unable to earn wages due to the closure of construction and other industries. Third, many were unable to buy food for their families since these rations are purchased on a day-to-day basis.[7] Finally, numerous cases of the use of excessive force by police in enforcing the lockdown have been documented.[8] Meanwhile, local authorities — overwhelmed by the myriad challenges of responding to the COVID-19 pandemic — simply lack the capacity to meet the needs of marginalized communities.

Operation Mercy Mission, Bangalore: A Glance from the Battlefield

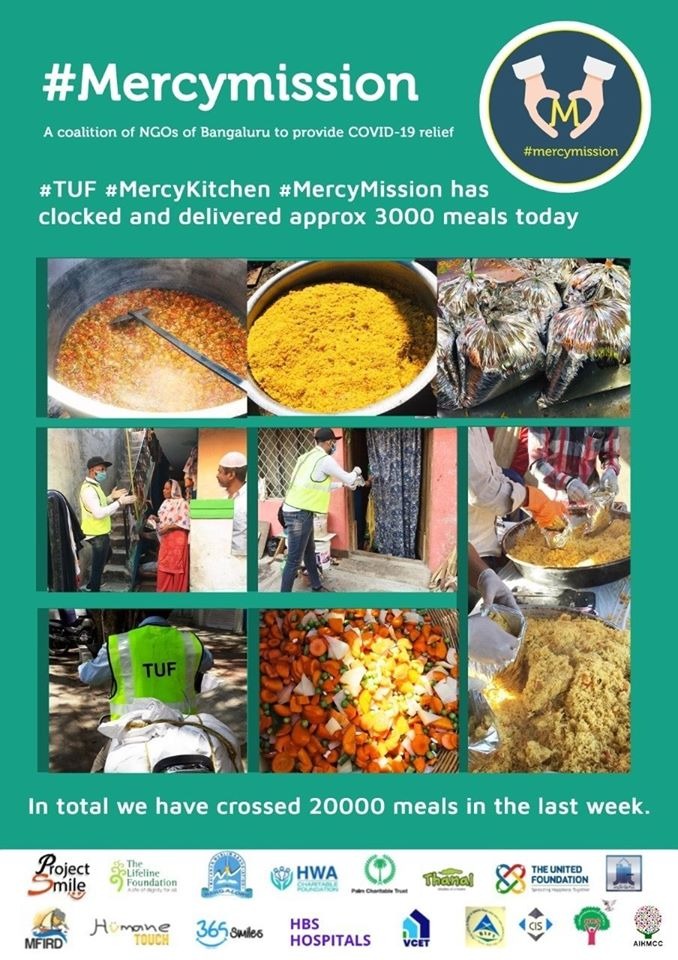

Civil society actors have stepped in to help fill gaps in underserved communities in Bangalore during this unprecedented public health emergency. About 20 such organizations — including The United Foundation, Our Nation, and Heera Foundation — formed an Emergency Response Team and began aid works under the campaign name called Mercy Mission.[9] All the members of this ad hoc coalition have deep roots in and have built strong networks throughout the city of Bangalore and abroad. For ten years or more, they have been actively working on the ground, conducting annual surveys and food distribution drives. This experience has enabled them to easily identify those most at risk and in need — widows, orphans, physically challenged, orphans, the ill or infirm, the elderly, single parents, wage workers, and so on.

NGO staff have procured raw materials from local vendors, with whom they have had long-standing relationship. Based on the trust and transparency established with the NGOs, the vendors have been ready to offer goods on credit and even to forgo payment in order to show their support for the initiative. The NGOs have been particular about not opting for cheaply priced goods, if that meant compromising on quality. Many vendors directly transported the goods to the slums, cutting out retailers, in order to prevent hoarding and profiteering.

To carry out relief work safely without being penalized for breaking the lockdown rules, the NGOs have needed to integrate the local police officers and municipal officials into their work. In the past, police officers had been invited to preside as Chief Guests in annual celebrations thus, establishing credibility with such institutions. Given that politicians are not quite involved with the NGOs in these areas, financially better-off individuals living in/near these slum areas, end up becoming caretakers of their immediate neighborhoods. These people have also helped with distribution.

Police authorities have put a system in place, whereby they provide NGOs with passes for every individual involved in on-ground relief work. To do so, the local members formed a team and submitted specific names to the police authorities to gain permission. Considering the infectious nature of the virus, no mass distribution has been done. Instead, NGOs have relied upon door-to-door distribution, arranging for two wheelers and auto rickshaws to deliver kits to households in various by-lanes.

Volunteers have been educated on the risk factors, and on the precautions to be taken during the distribution (e.g., the wearing of protective masks and gloves, the use of hand sanitizers, etc.). To avoid any chaos and crowding of people, the distribution has been carried out in the early morning hours.

To aggressively promote the campaign, a dedicated social media team (working remotely) has publicized efforts through Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram and Twitter. They also have approached many bloggers, influencers and celebrities to promoted the campaign on their respective social media accounts. Given that Instagram is the most popular platform, they have employed captivating hashtags, well-curated captions, and content.

Apart from social media, the NGOs have reached out to their existing lists of supporters, especially individuals who had contributed generously to their previous initiatives. The team also has introduced the concept, “Mercy Champions – motivating, activating agents,” whereby they honor individuals who pledge to donate a substantial number of food kits, and successfully accomplish fundraising for the same by the stipulated date. Additionally, the team has set up two helplines.

The team has pre-recorded various messages by prominent doctors and community members to gain credibility and has posted these audio clips on loop in several key areas and slums. In addition, these tapes have been added to volunteers’ vehicles to further drive home the messages. Volunteers have been instructed to ensure individuals are made aware of the virus and its basic features.

Finally, hosts of additional volunteer doctors and health workers have been recruited to ensure that timely advice and help is provided. These volunteers also advise communities regarding funeral services and final rites for individual that have succumbed to the virus.

In all, more than 1,000 volunteers from different parts of the city have helped coordinate on-the-ground and remote or virtual efforts on an ad hoc basis. In fact, most of the volunteers work offline and in their homes, with a very small number tasked with distributing food, thereby minimizing the risk of spreading the virus. [10] According to organizers of the initiative, more than 20,000 families were provided for within the first week of the shutdown, with daily increments of families helped by the organizations.

Similarly, many other organizations and actors across India have sprung up, taking charge and helping make sense of the chaos. National organizations such as Feeding India, Give India, Goonj, and many others have teamed up with local actors as well as crowd-funding websites to help bridge the gap, feed the hungry and organize funding for these operations.[11]

Civil Society’s Role Going Forward

In the coming weeks and months, the world will be beset by the virus and its deadly effects on cities, towns, and villages. Country-wide lockdowns will likely become a staple for developed and developing nations alike. Against this backdrop, civil society actors will play massively important roles in reducing the hardship faced by underserved communities.

First, they will become necessary lifelines and force multipliers for governments that will be struggling to deal with healthcare and essential commodities.

Second, they will likely be able to leverage their past actions and subsequent credibility to drive the message of social/physical distancing to populations that may be sceptical of government communication.

Third, they will help forge bonds of solidarity and common purpose between and among wealthier segments of society and marginalized populations.[12]

Fourth, by their actions and example, they will play a crucial role in creating alternate narratives of effective governance, holding government institutions to higher levels of performance and accountability.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the form of civil society-state cooperation on display in Bangalore and elsewhere during these extraordinary circumstances could provide the inspiration and the model for proactive partnerships aimed not just at preparing for the next public health emergency but also for ameliorating the living conditions for underserved populations in ordinary times.

[1] Suparna Chaudhry and Shubha Kamala Prasad, “How India plans to put 1.3 billion people on a coronavirus lockdown,” Washington Post, March 30, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/03/30/how-india-plans-put-13-billion-people-coronavirus-lockdown/.

[2] Vijayta Lalwani, “Coronavirus: ‘Why has Modi done this?’ Rajasthan workers walk back home from Gujarat,” Scroll.in, March 26, 2020, https://scroll.in/article/957245/coronavirus-after-lockdown-migrant-workers-take-a-long-walk-home-from-gujarat-to-rajasthan.

[3] “Causes of Urban Poverty in India,” Habitat for Humanity, https://www.habitatforhumanity.org.uk/blog/2018/08/causes-urban-poverty-india/.

[4] Dipankar DeSarkar, “Why Indian slums are allowed to grow, and then demolished”, LiveMint, December 18, 2015, https://www.livemint.com/Opinion/QkIgZjo9VO5edqjwqwfuFP/Why-Indian-slums-are-allowed-to-grow-and-then-demolished.html.

[5] Indranil De, “Slum improvement in India: determinants and approaches,” Housing Studies 32, 7 (2017): 990-1013.

[6] Arpita Raj, “Study reveals 2,000 slums in Bengaluru, govt lists only 597,” Times of India, July 23, 2018, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/bengaluru/study-reveals-2000-slums-in-bengaluru-govt-lists-only-597/articleshow/65096665.cms.

[7] “India’ s poorest ‘fear hunger may kill us before coronavirus,’ ” BBC, March 25, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-52002734.

[8] “Police struggle to enforce India’ s sweeping virus lockdown,” PBS, March 25, 2020, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/police-struggle-to-enforce-indias-sweeping-virus-lockdown.

[9] “NGOs, volunteers reach out to feed Bengaluru's hungry,” Times of India, April 1, 2020, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/bengaluru/ngos-volunteers-reach-out-to-feed-citys-hungry/articleshow/74920891.cms.

[10] The information included here was collected during the shutdown via telephone and text-based interviews with coordinators of the Mercy Mission coalition.

[11] Shemin Joy, “From food to hygiene kits, here is how NGOs are helping the poor fight against COVID-19,” Deccan Herald, March 27, 2020, https://www.deccanherald.com/national/north-and-central/from-food-to-hy….

[12] Scott Benario, “That Discomfort You’re Feeling Is Grief,” Harvard Business Review, March 23, 2020, https://hbr.org/2020/03/that-discomfort-youre-feeling-is-grief?fbclid=IwAR0PZFOsOOKrBipthBYfrQadjqFk7WgeMm7CcNgVic1q3kGxm9V5ZmGheOA.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.