In the aftermath of the fragmentation of the USSR, the South Caucasus region went through a period of transformational change, during which it had to redesign and rebuild its energy systems and energy security routes. The latest U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report demonstrates that anthropogenic warming has caused extreme temperatures, precipitation levels, and drought in the region. While Georgia has significant potential for additional clean energy generation and other climate change measures, the current pace of transformation needs to increase.

Climate change in the region

The latest IPCC report paints a grim picture of the global climate crisis resulting from ongoing anthropogenic warming. The South Caucasus has experienced a significant increase in extreme high temperatures, heavy precipitation levels, and agricultural and ecological droughts, with the latter even threatening hydroelectric power plants.

Additionally, both the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events have increased, and a report by the World Meteorological Organization describes 51 extreme weather events in the South Caucasus since 1990 (25 in Georgia). The total projected economic losses (without considering the loss of life) for just one-third of these extreme weather events — 17 in total — reach a staggering $1.11 billion.

High pollution levels in the region are a major contributing factor to these climate disasters. Georgia, for instance, is the world’s 37th worst polluted country, according to the 2020 World Air Quality Report. Despite these alarming statistics, Georgia has made consistent progress in advancing its energy transition.

A brief history of the energy sector in the South Caucasus

The collapse of the USSR and the re-emergence of ethnic conflicts resulted in a complicated energy situation in the South Caucasus in the 1990s. The old, centralized, and unreliable energy infrastructure was challenging for Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. However, the region’s difficult position was gradually transformed into an opportunity, as countries could now develop their own energy routes and climate agendas. Each country’s energy sector has its own unique features, as described below.

Azerbaijan started exporting its oil and gas reserves, which immediately contributed more than half of the country’s GDP. Armenia faced more challenges because it lacked natural resources, and it also had poor relations with Azerbaijan and Turkey. To address its recurring energy crises in the 1990s, Armenia decided to restart its two nuclear reactors, the only nuclear facilities in the South Caucasus, which were shut down just two years before the USSR’s collapse.

For its part, Georgia has developed significant hydroelectric power capacity for domestic consumption, and it has also benefited from its status as a gas transit hub (connecting East and West as well as North and South) for its Russian and Azeri partners. But the lack of distribution infrastructure for gas forces the population to use biomass for cooking and heating, which accounts for about 8% of the total primary energy supply. The resulting illegal logging has had a major impact on towns and villages, as massive deforestation has increased the risk and severity of extreme weather events, such as floods, landslides, and so on. This weak point could be transformed into an opportunity, however, as Georgia can expand its gas infrastructure and choose sustainable solutions such as heat pumps. Conversely, it could also become a wasted opportunity, as the country may fall into the gas lock-in effect, delaying the adoption of cleaner, more sustainable technologies.

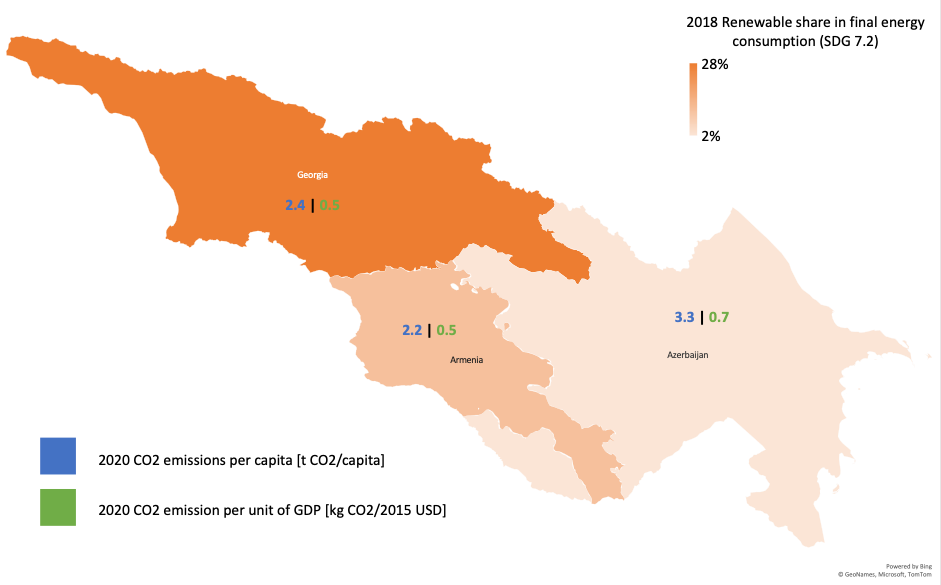

At present, Armenia (relying on hydroelectric and nuclear facilities) and Georgia (relying heavily on hydroelectric generation) score better than Azerbaijan (which uses mostly natural gas) on CO2 emissions per capita, due to their production of low-emission energy (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Key indicators on domestic energy sectors in South Caucasus

Climate policy challenges and opportunities in Georgia

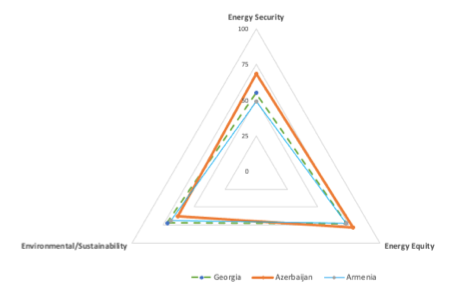

The opportunities and issues associated with Georgia’s energy path are highlighted in the country’s Energy Trilemma Index (Figure 2), which measures the equilibrium between three dimensions: reliable energy (energy security), affordable bills (energy equity), and environmental protection (sustainability). (Note: The higher the score, the better.) Among the South Caucasus countries, Georgia has the highest score on the sustainable dimension, due to its reliance on hydroelectric power, and relatively high energy security, but the low-income population still struggles with monthly energy bills.

Figure 2: South Caucasus countries’ Energy Trilemma Index scores

To reach this point, Georgia has made consistent progress by increasing the energy security and environmental protection vectors. More recently, the country joined the EU-Georgia Association Agreement and is now a contracting party of the Energy Community Treaty — developed by the Energy Community, the international organization that brings the EU and its neighbors closer, to create an integrated pan-European energy market — which represents its commitment to implementing the EU acquis in the energy sector.

As the International Energy Agency highlights, Georgian policies such as deregulation of the markets, privatization, reduced state intervention, and a favorable investment and taxation framework have transformed the country into a “star reformer.” Moreover, reforms in the forestry sector (expanding protected areas) as well as better fuel quality control have brought significant environmental benefits.

However, important issues are still to be addressed. Tbilisi is ranked 36th in the World Capital City Ranking by IQAir, among capital cities around the world, as 37% of the country’s vehicles are in the capital. They are responsible for 71% of total emissions, making the city’s air pollution almost three times higher than the World Health Organization’s recommended threshold.

Geopolitical context and potential ways forward

Geopolitics also play a significant role in Georgia’s energy transition process. The country has continuously attracted Chinese investments in transportation, real estate, tourist resorts, wood processing, and hydroelectric plants. Apart from the Chinese investment in the Khadori power plant (the first foreign-funded power station in the country), the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) — often labeled a “China-backed” investment body — is also interested in the Nenskra hydroelectric plant, which has sparked criticism among communities and climate activists.

As the EU aims to spearhead the global energy transition process through policies and funding for projects like renewable energy and hydrogen, the South Caucasus countries should increase their existing partnerships with the European bloc by adapting their regulatory frameworks to the EU acquis.

In addition to these legal measures, Georgia must also continue developing its investment frameworks. Scaling up renewable facilities and adopting energy efficiency measures are the main attractions for external investment. Additionally, the country must continue opening up and increasing the efficiency of its energy markets, thus sending the right market signals so that Georgia is viewed as an attractive and predictable investment destination. At the same time, Georgia must also provide financial and non-financial support for vulnerable consumers, without affecting investors’ interest in the region.

2022 marks a significant opportunity for the South Caucasus to speed up its climate agenda, as the conclusions from the 26th U.N. Climate Change Conference (COP26) urged countries to present concrete solutions for meeting the international objective of limiting global warming to 1.5°C. Some of the objectives defined at the Glasgow summit — like improved forestry management, methane emissions reduction, and phasing out polluting urban transport — offer immediate synergies with Georgia’s own pressing climate needs.

Andrei Covatariu is a Senior Research Associate at the Energy Policy Group, a Bucharest-based non-profit, independent think tank specializing in energy and climate policy. He was previously a Fellow with MEI’s Frontier Europe Initiative. The views expressed in this piece are his own.

Photo by Jonas Gratzer/LightRocket via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.