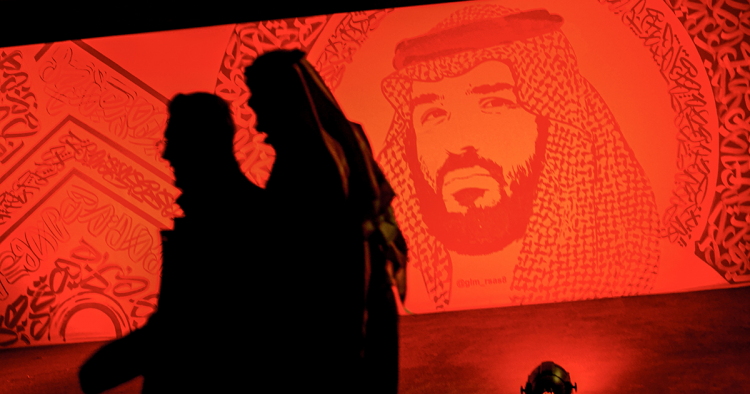

Saudi insiders describe Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, known as MbS, as mercurial and a micromanager. In addition to directing the murder of Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi, according to the CIA, plotting violence against former senior Saudi intelligence official Dr. Saad al-Jabri, whose children MbS still has imprisoned, and taking former Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri hostage, he allegedly locked up his own mother.

Raised with the illusion of the kingdom as an immense power, MbS is driven by a belief in his own infallibility and Saudi Arabia’s rightful place in the world. He has surrounded himself with those who would indulge him and pose little threat. His circle comprises younger, less experienced but presumably loyal princes in key ministerial positions as well as a few select, savvy, experienced older half-brothers and uncles loyal to his father. There are also several notable royal holdovers from smaller family branches with less claims on the throne, the odd competent technocrat, and a cadre of minions from across the military and security agencies and outside the House of Saud who do his dirty work.

MbS’s rise

King Salman removed King Abdullah’s brother Prince Muqrin as crown prince upon ascending the thrown in 2015, but not until MbS deposed Crown Prince Mohammed bin Nayef, known as MbN, in June 2017 during an extraordinary palace coup did he begin to truly flex his muscles in securing the pathway to rule. For his part, MbN, already suffering from fatigue, chronic medical issues, and various personal demons, ignored the warnings and advice from friends inside and outside the kingdom concerning MbS’s aspirations and guile.

MbN wrongly believed MbS would be appeased by his growing portfolio, such as taking ownership for the war in Yemen, and his understudy role as deputy crown prince, and would play by the rules that the House of Saud followed even prior to the establishment of the Allegiance Council, a body composed of one member from each house of founder Abdulaziz’s 34 sons who choose, validate, and secure royal succession.

With MbN out of the way, and some reports suggest given the unauthorized October 2017 warnings concerning his rivals passed on by former President Donald Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner, MbS directed a sweeping series of arrests framed as an anti-corruption purge. MbS primarily targeted former King Abdullah’s son Prince Miteb, head of the National Guard and considered a contender for the throne, as well as his three brothers, along with those considered loyal to their Shammar branch of the family. Miteb was eventually released in exchange for $1 billion and a loyalty pledge, along with brother Mishaal, but siblings Turki and Faisal remain under arrest. And in March 2020, MbS ultimately ordered MbN’s arrest, as well as that of the king’s remaining full brother, and MbS’s biggest royal critic, Prince Ahmed bin Abdulaziz, last of the famed “Sudari Seven.” That group of siblings was notable for its kings and crown princes, all full brothers from founding King Abdulaziz’s ostensibly favorite wife.

The key players and institutions

The purge might have neutralized the threats to MbS, but it also left him to run a country with an ailing king hardly in command, the cabinet in disarray, and professional Saudi bureaucrats looking over their shoulder. Prince Khalid bin Salman, MbS’s full brother, became the deputy defense minister, young Prince Abdulaziz bin Saud bin Nayef his interior minister, and little-known Prince Abdullah bin Bandar his National Guard minister. In all, perhaps the three most important and powerful Saudi institutions were placed in the hands of a trio who lacked experience and, more importantly wasta, the influence, gravitas, and connections required to cut deals across Saudi Arabia’s complex society.

Given that MbS himself holds the official portfolio as defense minister, his younger brother Khalid would inherit much of the day-to-day control. Unlike MbS, Khalid is American educated and reportedly flew combat missions as a Saudi Air Force officer. Presumably, this would earn him some credibility and a network within the Ministry of Defense, but not likely the respect of the armed forces’ most senior commanders. His time as ambassador to the U.S. showed him to be amiable enough, according to those with whom he interacted, but few Saudi watchers would judge him privy to his older brother’s decision making or in a position to exert influence.

Prince Abdullah bin Bandar has been minister of the National Guard since 2018. A critical institution for protecting the crown, the Guard is responsible for strategic facilities and resources and provides security for Mecca and Medina, in addition to the palace and the kingdom’s most sensitive installations. It operates outside of the armed forces’ chain of command and communications networks and is exceptionally well-funded, even by Saudi standards. Unlike his predecessor, Prince Miteb, National Guard Minister Prince Abdullah possesses neither military nor security training. His merit stems presumably from loyalty, or the absence of threatening ambition. Prince Abdullah has a long, close association with MbS, with whom he is a contemporary in age. His father, Prince Bandar bin Abdulaziz, removed himself from the line of succession long before his death. Prince Abdullah runs an organization, however, in which most of the commanders beneath him were advanced with King Abdullah’s and Prince Miteb’s favor.

The Guard’s professional, uniformed commander-in-chief is Maj. Gen. Mansour al-Issa. It is perhaps telling that rather than coming up through the Guard’s combat elements, Issa spent his career on the administrative side, and most of that in procurement. The majority of the military specialty courses he took were in defense resources management, budget preparation, and accounting. One might speculate about the degree of respect with which the Guard’s combat commanders hold him should Prince Miteb survive to instigate a challenge.

Minister of Interior Prince Abdulaziz bin Saud’s father is the governor of the oil-rich Eastern Province, Prince Saud bin Nayef, who happens to be MbN’s full brother. Prince Abdulaziz oversees Saudi Arabia’s civilian security services, including its police and intelligence agencies, and by extension, their internal monitoring capabilities. MbS might be gambling on the interior minister’s loyalty given that his father was passed over for succession by younger brother MbN. Prince Saud previously managed Crown Prince (now King) Salman’s office so might be considered vetted. That all having been said, some Saudis contend that Prince Abdulaziz and his father Prince Saud were both briefly detained and questioned in March 2020 along with MbN, Prince Ahmed bin Abdulaziz, and Prince Nawaf bin Nayef, as part of that wider series of royal arrests.

MbS retained his half-brother Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman as oil minister, given his years of experience and connections. As Mecca governor, he appointed an uncle loyal to his father, Prince Khalid bin Faisal bin Abdulaziz. According to insiders, Prince Khalid reportedly took on the role King Salman long exercised as the strong-armed family fixer, using his influence to encourage royal family unity and discourage opposition.

MbS has also secured loyalty from Prince Bandar bin Sultan and Prince Turki bin Faisal by installing their children in prominent positions. These princes’ lines are little threat today to compete for the throne but they wield considerable influence. They make for good champions and spokespersons on MbS’s behalf should internal challenges arise, each having served as ambassadors to both the U.S. and the U.K. and as intelligence chief. Prince Bandar’s daughter, Princess Reema bint Bandar, is the Saudi ambassador to the U.S. and his son, Prince Khalid bin Bandar, the ambassador to the U.K. Prince Turki’s son, Prince Abdulaziz bin Turki, is the minister of sports. Not having been fans of MbN, but faithful to former King Abdullah, if not always pleased by his decisions, their loyalties have been facilitated through plum positions for their children. But as such, and given the questionable reliability of lavish princely stipends under MbS and how quickly the political winds might change, their support is not necessarily written in stone.

Technocrat Yasir al-Rumayyan, a former investment banker and long-time MbS adviser, is central to achieving the crown prince’s economic goals. Rumayyan is the manager of the kingdom’s Public Investment Fund (its sovereign wealth fund) and the chairman of Saudi Aramco, holding the keys to the kingdom’s vast wealth. Rumayyan reportedly met several times with Kushner during Trump’s time in office and after, the latter when discussing investment pitches from both the former president’s son-in-law and former Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin. Saudi Arabia ultimately awarded $2 billion to Kushner’s firm, Affinity Partners, and $1 billion to the former Treasury secretary’s, Liberty Strategic Capital. Rumayyan reportedly expressed doubts over Kushner’s investment capabilities, but the decision was ultimately MbS’s to make.

MbS depends on a circle of loyalists from outside of the House of Saud to direct his most sensitive security and intelligence efforts. He sidelined, but did not fire, a number of the professionals who served under King Abdullah and former Crown Prince MbN, who had long worked under his father at the Ministry of Interior before succeeding him as minister. After securing their loyalty oaths, MbS retained the chiefs of the General Intelligence Presidency (external intelligence), Khalid bin Ali al-Humaidan, and the General Investigation Directorate, or Mabahith (internal intelligence and security), Abdulaziz bin Mohammed al-Huwairini.

The two intelligence chiefs were good at their jobs and enjoyed strong relationships with Western intelligence services built on years of cooperation and constructive interaction. But they both had long and loyally served MbN and his father, Prince Nayef bin Abdulaziz. The Mabahith director was reportedly detained but later released, according to insiders, and promoted to a higher rank, albeit with fewer day-to-day responsibilities. But hedging his bets, MbS appointed Maj. Gen. Ahmad Asiri as the intelligence service’s deputy, no doubt to keep an eye on Humaidan.

A former Saudi Air Defense officer, royal court adviser, and one-time Saudi spokesperson for the war in Yemen who reportedly became close to MbS when the crown prince took on the defense portfolio, Asiri was identified as among the ringleaders in Mr. Khashoggi’s murder. Although reportedly fired as his penance, he was found not guilty of the charge by a questionable Saudi court and has purportedly been seen living well and traveling since.

Asiri is cut from the same cloth as Saud al-Qahtani, another top former, and perhaps current, aide to the crown prince, depending on who you ask. MbS pulled Qahtani, like Asiri also named in Mr. Khashoggi’s murder, into his circle from outside the palace. A royal court media adviser, Qahtani was appointed as an adviser to the office of the crown prince during King Abdullah’s rule and was inherited. But the Asiri and Qahtani tribes have historically maintained a significant presence across the Saudi security services. Having members of theses tribes on whom he could depend in his circle and willing to do his bidding would have been a clever choice.

The Saudi ruling family has long drawn strength and legitimacy from an alliance with the clergy. Sheikh Abdulaziz al-Sheikh, Saudi Arabia’s grand mufti and a direct descendent of Ibn Wahhab, has been publicly supportive of MbS despite a series of reforms that significantly undermined his influence, the religious elite’s power, and his budget. The al-Sheikh family is well integrated into the House of Saud through marriage. But even if his loyalty is secure, Sheikh Abdulaziz does not necessarily represent, or control, the most conservative elements of Saudi society, some of which do not appreciate the crown prince’s social and cultural changes.

MbS’s rule

At the end of the day, it would seem that MbS is taking what he believes to be a page from his grandfather, Saudi Arabia’s founder, King Abdulaziz, who secured the kingdom violently and did not share power. But even King Abdulaziz courted the clerics’ support and that of the more conservative tribes, only cracking down on the Wahhabis when they grew too independent and bold. MbS’s rule is founded on a similar concept of total control at the very top, in contrast to the broader consensus across the House of Saud and Saudi society with which his more recent predecessors had ruled. Going it alone certainly frees him from internal debate, but it also deprives him of input concerning not only alternative perspectives, but rumblings beneath the surface beyond the scope or control of his lieutenants.

Douglas London is the author of "The Recruiter: Spying and the Lost Art of American Intelligence." He teaches intelligence studies at Georgetown University's School of Foreign Service and is a nonresident scholar at the Middle East Institute. London served in the CIA's Clandestine Service for over 34 years, mostly in the Middle East, South and Central Asia and Africa, including three assignments as a Chief of Station. Follow him on Twitter @DouglasLondon5. The views expressed in this piece are his own.

Photo by FAYEZ NURELDINE/AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.