Originally posted August 2010

Over the last 15 years or so, policy-makers and government representatives have repeatedly referred to readmission in official discourses and statements. Readmission is the process through which individuals who are not allowed to stay on the territory of a country (e.g., unauthorized migrants, rejected asylum-seekers or stateless persons) are expelled or removed, whether in a coercive manner or not.

Just like deportation, readmission is a form of expulsion if we assume that “the word ‘expulsion’ is commonly used to describe that exercise of state power which secures the removal, either ‘voluntarily,’ under threat of forcible removal, or forcibly, of an alien from the territory of a State.”[1] Readmission has become part and parcel of the immigration control systems consolidated by countries of origin, transit, and destination. Technically, readmission as an administrative procedure requires cooperation at the bilateral level with the country to which the readmitted or removed persons are to be relocated. Readmission permeates both domestic and foreign affairs. Practically, it is aimed at the swift removal of aliens who are viewed as being unauthorized.

The practice of readmission, viewed as a form of expulsion, did not start fifteen years ago. Readmission is, in its various forms, perhaps as old as the exercise, whether soft or violent, of state sovereignty and interventionism designed to regulate the entry and exit of aliens. In the early 20th century, the principle of readmission, based on the obligation to take back one’s own nationals who are found in unlawful conditions, was expressed in various bilateral agreements in Western Europe, even if, as Kay Hailbronner has stressed, “representatives of some states voiced reservations about an absolute duty to reaccept [their nationals].”[2]

Additionally, Aristide Zolberg shows that, as early as the 19th century, in the United States, “deportation did not constitute a punishment but was merely an administrative device for returning unwelcome and undesirable aliens to their own countries.”[3] This assumption holds true when it comes to explaining readmission as a form of police control exerted by national law-enforcement agencies or administrations to categorize aliens and citizens alike.

However, in today’s international relations, cooperation on readmission involves more than an “absolute duty” or a “mere administrative device.”

When dealing with readmission we have to take into consideration the fact that state-to-state cooperation is based on asymmetric costs and benefits, for it involves two contracting parties (i.e., the country of destination and the country of origin or transit) that do not necessarily share the same interests in pursuing cooperation. Nor do they face the same domestic, regional, and international implications.

Despite their being framed in a reciprocal context, readmission agreements, or treaties, contain mutual obligations that cannot apply equally to both contracting parties owing to the asymmetrical impact of the effective implementation of the agreements, and to the different structural institutional and legal capacity of both contracting parties for dealing with the removal of unauthorized aliens, whether these are identified as nationals of the contracting parties or as third-country nationals transiting through the territory of a contracting party. These are the main reasons for which I have argued that readmission agreements are characterized by unbalanced reciprocities.[4]

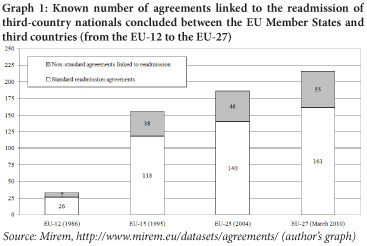

Admittedly, international relations abound with agreements based on asymmetric costs and benefits.[5] However, what makes cooperation on readmission quite extraordinary lies in the fact that, despite the aforementioned unbalanced reciprocities, the number of bilateral agreements linked to readmission has skyrocketed since the early 1990s. This sharp increase is also surprising when considering that readmission agreements only facilitate cooperation at the bilateral level. In other words, they are not a sine qua non when addressing readmission or removal.

This paradox deserves further attention, for it raises four questions regarding 1) the factors shaping the cooperation on readmission, 2) the patterns of cooperation sustaining states’ modus operandi, 3) the effectiveness and utility of the cooperation on readmission, and 4) its impact on the conditions of readmitted aliens. The contributions contained in this volume address these questions, with specific reference to the Euro-Mediterranean context.

The Faces of Cooperation on Readmission

States differ markedly in terms of cooperation on readmission,[6] probably owing to the types of flows affecting their respective national territory. At the same time, however, the ways in which states codify their interaction over time play a crucial role in shaping their patterns of cooperation on readmission.

This assumption implies that state-to-state interaction, in its broadest sense, impacts on the nature of cooperative patterns and on states’ responsiveness to uncertainties. Sometimes, they may reciprocally commit themselves to cooperating on readmission by concluding an agreement because both contracting parties view the formalization as being valuable to each other’s interests, beyond the resilient unbalanced reciprocities that characterize the cooperation. Other times, however, they may decide to readjust their cooperation in order to “reduce the chance that either state will want to incur the costs of reneging or be forced to endure an unsatisfactory division of gains for long periods.”[7] Circumstances and uncertainties alike change over time, making flexible arrangements preferable over rigid ones.

In previous works,[8] I have explained that simply making an inventory of the standard readmission agreements concluded at the bilateral level in the Euro-Mediterranean area would not suffice to illustrate the proliferation of cooperative patterns on readmission, for these have become highly diversified as a result of various concomitant factors. I elaborate on this in the next sections.

The Standard Approach

Standard readmission agreements have been subject to various studies, above all by scholars in migration and asylum law[9] who, for example, stressed the reciprocal obligations contained in a readmission agreement as well as the procedures that need to be respected to identify undocumented persons (unauthorized migrants, rejected asylum seekers, stateless persons, unaccompanied minors) to subsequently remove them out of the territory of a destination country.[10] Given the existence of a huge literature in migration law, the point here is not to elaborate on a legal approach to readmission agreements. Nevertheless, it is important to recall some essential legal aspects linked with states’ accountability in the field of readmission.

When concluding a standard readmission agreement, the contracting parties agree to carry out removal procedures without unnecessary formalities and within reasonable time limits, with due respect of their duties under their national legislation and the international agreements on human rights and the protection of the status of refugees, in accordance with the 1951 Geneva Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 protocol, the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the 1984 UN Convention against torture, and more recently the 2000 European Charter on Fundamental Rights. All of these internationally recognized instruments oblige states not to expel persons (whether migrants or not) to countries and territories where their life or freedom would be threatened in any manner whatsoever.

Despite the letter of these agreements, various human rights organizations and associations in Europe and abroad have repeatedly denounced the lack of transparency that surrounds the implementation of readmission agreements and removal operations. Such public denunciations have not only questioned the compliance with the obligations and principles contained in bilateral readmission agreements, but also have led to growing public concerns regarding respect for the rights and safety of the expelled persons.

In fact, the willingness of a country of origin to conclude a readmission agreement does not mean that it has the legal institutional and structural capacity to deal with the removal of its nationals, let alone the removal of foreign nationals and the protection of their rights. Nor does it mean that the agreement will be effectively or fully implemented in the long run, for it involves two contracting parties that do not necessarily share the same interest in the bilateral cooperation on readmission. Nor do they face the same implications, as previously stated. These considerations are important to show that the conclusion of a readmission agreement is motivated by expected benefits which are unequally perceived by the contracting parties, on the one hand, and that the agreement’s implementation is based on a fragile balance between the concrete benefits and costs attached to it, on the other.

The Fragile Balance Between Costs and Benefits

Whereas a destination country has a vested interest in concluding readmission agreements to facilitate the removal of unauthorized migrants, the interest of a country of origin may be less evident, above all if its economy remains dependent on the revenues of its (legal and unauthorized) expatriates living abroad, or when migration continues to be viewed as a safety valve to relieve pressure on domestic unemployment. This statement is particularly true regarding the bilateral negotiations on readmission between some EU Member States and countries in the South Mediterranean and Africa where economic and political differentials are significant. Special trade concessions, preferential entry quotas for economic migrants, technical cooperation and assistance, increased development aid, and entry visa facilitations have been the most common incentives used by the EU-27 Member States to induce countries in the South Mediterranean and Africa to cooperate on readmission.

However, experience has shown on various occasions that compensatory measures — which constitute a form of incentive — may not always induce a third country to conclude a standard readmission agreement. Moreover, even when a standard agreement is concluded, the high costs stemming from the implementation of the agreement make the extent of the actual cooperation highly uncertain. For a country of origin, such costs are not just financial. Nor do the costs stem only from the structural institutional and legal reforms needed to implement the cooperation. They also lie in the unpopularity of the standard readmission agreement and in the fact that its full implementation might have a negative impact on the relationship between the state and society in a country of origin.

Grafting Readmission on to Other Policy Areas

If we follow the conventional wisdom, we may believe that states negotiate and conclude readmission agreements as an end in itself. However, as the contributions in this volume show, readmission agreements are rarely an end in itself but rather one of the many ways to consolidate a broader bilateral cooperative framework, including other strategic (and perhaps more crucial) policy areas such as security, energy, development aid, and police cooperation. Often, the decision to cooperate on readmission results from a form of rapprochement that shapes the intensity of the quid pro quo.

There are various examples which support this argument. In February 1992, Morocco and Spain signed a readmission agreement in the wake of a reconciliation process which materialized following the signing of the Treaty of Good-neighborliness and Friendly Cooperation on July 4, 1991. Morocco’s acceptance to conclude this agreement was motivated by its ambition to acquire a special status in its political and economic relationships with the European Union.[11] Likewise, in January 2007 Italy and Egypt concluded a readmission agreement as a result of reinforced bilateral exchanges between the two countries. Such reinforced exchanges have allowed Egypt to benefit from a bilateral debt swap agreement, as well as from trade concessions for its agricultural produce and, additionally, temporary entry quotas for Egyptian nationals in Italy. Importantly, the rapprochement between Italy and Egypt was key to integrating the latter into the G14[12] while acquiring enhanced regime legitimacy at the international level. Similarly, the bilateral agreement on the circulation of persons and readmission concluded in July 2006 between the United Kingdom and Algeria, while still not in force, is not an exception to the rule. This agreement, limited to the removal of the nationals of the contracting parties, took place in the context of a whole round of negotiations, including such strategic issues as energy security, the fight against terrorism, and police cooperation. These strategic issues have become top priorities in the bilateral relations between the United Kingdom and Algeria, particularly following the July 2005 London bombings and the ensuing G8 meeting in Gleneagles that Algeria also attended.[13]

These few examples are important to show that the issue of readmission weaves its way through various policy areas. It has been, as it were, grafted on to other issues of “high politics,” such as the fight against international terrorism, energy security, reconciliation process, reinforced border controls, special trade concessions, and, last but not least, the search for regime legitimacy and strategic alliances. It is this whole bilateral cooperative framework which secures a minimum operability in the cooperation on readmission more than the “reciprocal” and binding obligations contained in a standard readmission agreement. Policy-makers know that the reciprocal obligations contained in a standard readmission agreement are too asymmetrical to secure its concrete implementation in the long run. They also know that grafting the cooperation on readmission onto other policy areas may compensate for the unbalanced reciprocities characterizing the cooperation on readmission or removal. It is because of this awareness, which arguably resulted from a learning process, that the web of readmission agreements has acquired formidable dimensions over the last fifteen years or so. However, this tells us just a part of the story.

The Drive for Flexibility

We have seen that cooperative mechanisms may be formalized, as is often the case, through the conclusion of standard readmission agreements if both contracting parties view this as being valuable to each other’s interests. However, as mentioned before, we need to look beyond standard readmission agreements to provide a more complete picture of the various mechanisms and cooperative instruments that have emerged recently.

Under some circumstances, both contracting parties may agree to cooperate on readmission without necessarily formalizing their cooperation with a standard agreement. They may opt for different ways of dealing with readmission through exchanges of letters and memoranda of understanding or by choosing to frame their cooperation via other types of deals (e.g., police cooperation agreements, arrangements, and pacts).

The main rationale for the adoption of non-standard agreements is to secure bilateral cooperation on migration management, including readmission, and to respond flexibly to new situations fraught with uncertainties. Because of the uncertainty surrounding the concrete implementation of the cooperative agreement over time, states may want to secure their credibility through agreements “that include the proper amount of flexibility and thereby create for themselves a kind of international insurance.”[14] With reference to the cooperation on readmission, this argument does not imply that states do not make any credible commitments when signing agreements. To the contrary, it is because of their search for credibility that they may opt for flexible patterns of cooperation when it comes to dealing with highly sensitive matters such as readmission or removal.

Credibility is a core issue in the cooperation on readmission, for it symbolically buttresses the centrality of the state and its law enforcement agencies in the management of international migration. The cooperation on readmission has often been presented by European leaders to their constituencies and the international community as an integral part of the fight against illegal migration and as instruments protecting their immigration and asylum systems.

This cause-and-effect relationship, predicated by political leaders, shows to constituencies that governments have the credible ability to respond to and even anticipate shocks (e.g., mass arrivals of unauthorized migrants), because of the existence of specific mechanisms. However, shocks generate uncertainty which might, in turn, jeopardize the effective cooperation on readmission, particularly when it comes to addressing the pressing problem of re-documentation, that is, the delivery of travel documents or laissez-passers by the consular authorities of the third country needed to remove undocumented migrants. It is a well-known fact that the above-mentioned readmission agreement concluded in 1992 between Spain and Morocco has never been fully implemented. This agreement foresees the readmission of the nationals of the contracting parties as well as the third-country nationals. Diplomatic tensions between the two countries, particularly under the José María Aznar government (1996−2004), have hampered the bilateral cooperation on readmission. Thus far, Morocco’s cooperation on the delivery of travel documents at the request of the Spanish authorities has been highly erratic.[15]

Changing circumstances may upset the balance of perceived costs and benefits and be conducive to defection. Because of the uncertainties surrounding the concrete implementation of a readmission agreement, various EU Member States have been prone to show some flexibility in readjusting their patterns of cooperation with some third countries in order to address the aforementioned problem of re-documentation and the swift delivery of travel documents or laissez-passers. The faster the delivery of travel documents, the shorter the duration of detention, and the cheaper its costs.

The Non-Standard Approach

Over the last decades, France, Greece, Italy, and Spain have been at the forefront of a new wave of agreements linked to readmission. They are linked to readmission in that they cannot be properly dubbed readmission agreements, in the technical sense. These agreements (e.g., memoranda of understanding, arrangements, pacts, and police cooperation agreements including a clause on readmission) are often based on a three-pronged approach covering 1) the fight against unauthorized migration, including the issue of readmission, 2) the reinforced control of borders, including ad hoc technical assistance, and 3) the joint management of labor migration with third countries of origin, including enhanced development aid. For example, this approach is enshrined in Spain’s Africa Plan as well as in France’s pacts on the concerted management of international migration and co-development.

As mentioned earlier, circumstances change over time, and uncertainty might severely upset the fragile balance of costs and benefits linked to the bilateral cooperation on readmission. These non-standard agreements have been responsive to various factors. First, they tend to lower the cost of defection or reneging on the agreement, for they can be renegotiated easily in order to respond to new contingencies. In contrast with standard readmission agreements, they do not require a lengthy ratification process when renegotiation takes place. Second, they lower the public visibility of the cooperation on readmission by placing it in a broader framework of interaction. This element is particularly relevant for emigration countries located in the South Mediterranean and in Africa, where the cooperation on readmission is politically unpopular and where governments are reluctant to publicize it. Under these circumstances, governments in emigration countries would become more acquiescent in cooperating in the framework of agreements linked to readmission while being, at the same time, in a position to publicly abhor the use of standard readmission agreements. Third, they allow for flexible and operable solutions aimed at addressing the need for cooperation on readmission. The agenda remains unchanged, but the operability of the cooperation on readmission has been prioritized over its formalization. Fourth, non-standard agreements linked to readmission are by their nature difficult to detect and monitor, for they are not necessarily published in official bulletins. Nor are they always recorded in official documents or correspondence.

There is no question that flexibility has acquired mounting importance in the practice of readmission over the last decade. Indeed, the graph below shows that the number of non-standard agreements linked to readmission concluded between the EU Member States and third countries has risen over the last decade, together with the increase in standard readmission agreements.

The reported growth in standard readmission agreements stems from the gradual enlargement of the European Union and from the fact that some third countries regarded the conclusion of such readmission agreements as a way of consolidating their relations with the European bloc. Third countries in Eastern Europe and the Western Balkans have had a concrete incentive to cooperate on readmission. Their option to cooperate could also be justified to their constituencies while referring to the expected, though unclear prospect of accession into the EU (e.g., Croatia, Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, Serbia, Bosnia Herzegovina, and, more recently, Kosovo). Moreover, additional incentives included the possibility to benefit from preferential visa facilitation agreements.[16]

In contrast with countries located in Eastern Europe and the Western Balkans, third countries in the Mediterranean and in Africa have, from a general point of view, been involved in flexible arrangements aimed at cooperating on readmission (see Paolo Cuttitta’s chapter). As previously mentioned, incentives to conclude (visible and unpopular) standard readmission agreements do not fully explain the proliferation of cooperative agreements linked to readmission, for they may not always offset the unbalanced reciprocities that characterize the cooperation on readmission.

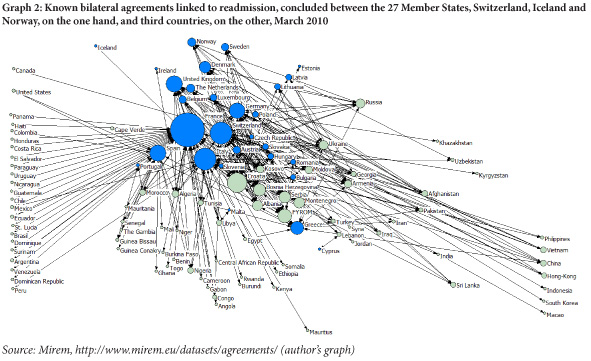

The growing number of non-standard agreements has had a certain bearing on the proliferation of agreements linked to readmission. Today, the web of bilateral agreements linked to readmission has grown considerably, involving more than one hundred countries throughout the world. Graph 2 schematically illustrates the bilateral agreements linked to readmission concluded between the 27 EU Member States plus Iceland, Norway, and Switzerland (depicted in blue), on the one hand, and third countries (in light green), on the other.[17]

The size of each circle (or node) has been weighted with regard to the total number of bilateral agreements linked to readmission (whether standard or not) concluded between the two groups of countries. In other words, the bigger the circle, the denser the web of agreements linked to readmission in which each country is involved. Among the blue-colored 27 EU Member States (plus Iceland, Norway and Switzerland), Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Spain, and Switzerland have been the most involved in bilateral cooperation on readmission. Clearly, their respective patterns of cooperation vary with the type of flows affecting their national territories, geographical proximity, the nature and intensity of their interaction (in terms of power relations) and, finally, with the third country’s responsiveness to the need for enhanced cooperation on readmission.

Incidentally, Denmark and Germany — like Switzerland — tend to cooperate on readmission through the conclusion of standard agreements. This inclination may stem from the fact that their negotiations have been mainly concluded with third countries in Eastern Europe and the Western Balkans (mainly Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia Herzegovina, Macedonia, Albania, Moldova, Ukraine, and Kosovo) which, as explained earlier, have had a concrete incentive to cooperate on readmission and to formalize their cooperation while grafting it onto other strategic policy areas.

Conversely, Italy, Greece, France, and Spain have been confronted with the need to adapt their respective cooperative patterns, above all when it comes to interacting on the issue of readmission with some Mediterranean and African countries. Past experience has already shown that Mediterranean third countries have been less inclined to conclude standard readmission agreements, or even to fully implement them when such agreements were concluded, owing to the potentially disruptive impact of their (visible) commitments on the domestic market and social stability, and on their external relations with their African neighbors. At the same time, however, other factors have justified such ad hoc readjustments.

Explaining Patterns of Cooperation on Readmission

The practice of readmission is, as it were, yoked to complex contingencies. By practice, I mean that two states may decide to implement readmission without necessarily tying their hands with an agreement, whether standard or not. Under these circumstances, the practice may be viewed as being sporadic. What really matters is the assurance that the requested state (i.e., a country of transit or of origin) will be responsive to the expectations of the requesting state (i.e., a destination country). For example, a country of origin may agree to issue travel documents, at the request of a destination country, that are needed to expel or readmit undocumented migrants without necessarily having an agreement. The issuance of travel documents will be based on a form of tacit assurance that the requested country will be responsive.

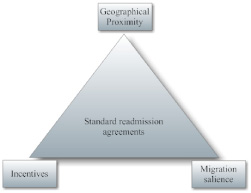

The transition from practice to cooperation on readmission occurs, however, when the responsiveness to perceived exigencies has to be ensured on a more regular basis, not sporadically. A country of destination may seek to secure the regular responsiveness of its counterpart by concluding a treaty or a standard agreement based on reciprocal commitments and obligations to cooperate on readmission. At the outset, three interrelated factors may lead to the conclusion of readmission agreements at the request of a destination country.

The first factor pertains to geographical proximity. Countries sharing a common land or maritime border may have a higher propensity to cooperate on readmission. This assumption holds true in the case of Spain and Morocco which concluded a standard readmission agreement in 1992. Conversely, it is not explanatory in the case of neighboring Portugal and Morocco which, despite their common maritime border, have no bilateral standard readmission agreement. To account for this contrast we need to combine geographical proximity with other factors.

The second factor refers to migration salience. This reflects the extent to which migration and mobility have become a salient component of the development of the bilateral relations between two countries. Migration, or the movement of people, has become over time a key feature of their historical relations. Migration salience may be observed in post-colonial regimes, where the mobility of people is part and parcel of the interaction between former colonial powers and their former colonies. It may also apply to two countries characterized by repeated exchanges of people and the presence of large émigré communities. If viewed as being significant in the negotiation process, migration salience might hinder the conclusion of a standard readmission agreement, for the unpopular conclusion of such an agreement would jeopardize the diplomatic relations between the two countries. In other words, migration salience may turn out to be detrimental to the conclusion of standard readmission agreements, let alone their concrete implementation.

The third factor pertains to incentives. Expected absolute and relative gains allow the unbalanced reciprocities characterizing the cooperation on readmission to be overcome. This has often explained the reasons for which various countries of origin and of transit in the Western Balkans and in Eastern Europe have had a vested interest to conclude readmission agreements at the request of EU Member States. Their responsiveness was conditionally linked with an array of incentives including, among others, visa facilitation agreements, trade concessions, preferential entry quotas for given commodities, technical assistance, and increased development aid. However, incentives do not always explain or secure cooperation on readmission in the long term. Under some circumstances, expected benefits might not always offset the costs of the cooperation on readmission. Costs are not only linked with the concrete implementation of the agreement and its consequences, but also with its unpopularity at the social level. Moreover, even when incentives were viewed, at a certain point in time, as being significant enough to cooperate on readmission, the (unintended) costs of the cooperation incurred by a country of origin or transit might eventually jeopardize the cooperative relationship and be conducive to reneging. Incentives do not always offset the fragile balance of costs and benefits; above all, when migration salience might hinder the cooperation on readmission.

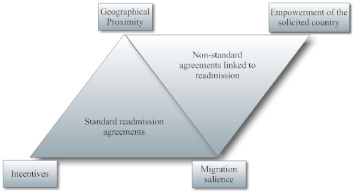

Arguably, none of the three factors described above could individually account for states’ intervention in the field of readmission. Cooperation on readmission lies at the intersection of these three factors. Combined together, these factors delimit the boundaries of a triangular domain where the cooperation, based on a standard readmission agreement, is practicable and where the significance of each of the three factors will be weighted against each other, over time and in an ad hoc manner.

However, this triangular domain provides an incomplete explanation when it comes to analyzing the emergence of non-standard agreements linked to readmission (e.g., memoranda of understanding, pacts, exchanges of letters, police cooperation agreement including a clause on readmission). The gradual importance that such agreements are acquiring at the bilateral level results from the consideration of a fourth factor that has emerged over the last few years prompting some EU Member States to adjust or even readjust their cooperative framework with some non-EU source countries. This readjustment was not only motivated by the need for flexibility with a view to securing the operability of the cooperation on readmission. It also stemmed from the perceptible empowerment of some source countries as a result of their proactive involvement in the reinforced police control of the EU external borders. Actually, with reference to the South Mediterranean, countries like Morocco, Algeria, Libya, Tunisia, Turkey, and Egypt have become gradually aware of their empowerment. Their cooperation on border controls has not only allowed these Mediterranean countries to play the efficiency card in the field of migration and border management, while gaining further international credibility and regime legitimacy; but it has also allowed them to acquire a strategic position in migration and border management talks on which they tend to capitalize. There can be no question that this perceptible empowerment has had serious implications on the ways in which the cooperation on readmission has been adaptively addressed, reconfigured and codified, leading to the conclusion of (flexible and less visible) patterns of cooperation on readmission.

The combination of the four factors shown on the graph below allows the conclusion of agreements linked to readmission (whether standard or not) to be better explained.

Various case studies support the analytical relevance of the above diagram. To give just a few examples, France had to adjust its cooperative patterns on readmission with most North and West African countries as a result of this combination: First, because the management of labor migration has been part and parcel of France’s diplomatic relations with these third countries.

The (visible) negotiation of an unpopular standard readmission agreement would have jeopardized France’s relations with these countries (i.e., migration salience). Second, because the aforementioned third countries have acquired a strategic position through their participation in the reinforced control of the EU external borders and in the fight against illegal migration and international terrorism (i.e., empowerment). Bringing pressure to bear on these neighboring (and strategic) third countries to conclude a standard readmission agreement would have been difficult, if not counterproductive.

Conversely, France was in a position to negotiate standard readmission agreements with numerous Latin American countries, for their visible conclusion would not have significantly impaired bilateral relations, and because migration management does not constitute, for now, an issue of high politics in the relations between these geographically remote countries and France (migration salience is not a significant factor). Under these circumstances, France reinforced its cooperation on the exemption of short-term visas to the nationals of cooperative Latin American countries (i.e., incentives) by means of bilateral exchanges of letters. Conversely, Spain has few readmission agreements with Latin American countries, probably owing to the fact that migration management constitutes an issue of high politics (i.e., migration salience) in the history of its bilateral relations with Latin American countries.

It is the combination of these four factors that seems to account for the increase in the number of agreements linked to readmission while at the same time explaining their diversity. However, there exist additional dynamics sustaining the proliferation of these agreements, despite the unbalanced reciprocities that characterize them. Other driving forces need to be considered to account for this paradox.

The Driving Forces of the Cooperation on Readmission

I began by analyzing several patterns of cooperation on readmission by highlighting the broader strategic framework of interaction in which they are embedded and by identifying the key factors shaping at the same time their diversity. I also emphasized the fragile balance of costs and benefits linked with the cooperation on readmission and showed that states do not share the same interests in the cooperative agreement. They may expect to gain more through cooperation or to fare well compared with other states.

There can be no question that relative-gains-seeking can help explain the reasons for which two state actors cooperate on readmission. Such relative gains do motivate state actors to cooperate or not. However, this assumption does not necessarily mean that “relative gains pervade international politics nearly enough to make the strong realist position hold in general.”[18] There also exist “particular systems,”[19] shaped by beliefs, values, and dominant schemes of understanding that can have an impact on the conditions conducive to cooperation, as well as on states’ perceptions and change of behavior.

The recognition of such systems is important insofar as it lays emphasis on the need to consider the existence of a causal link between beliefs and (perceived) interests, subjectivities, and priorities, as well as between values and policy agendas. The point is not so much to analyze the costs and benefits linked with the cooperation on readmission between two state actors (see Emanuela Paoletti’s chapter). The main question lies in exploring the system whereby the cooperation on readmission has become more predictable over the last ten years or so. Investigating such a system, or “concourse structure,” as described by John Dryzek et al.,[20] is key to understanding the overriding driving forces which have arguably contributed to the increase in the number of cooperative agreements linked to readmission, again despite the unbalanced reciprocities that characterize them.

Expressions of a “Concourse Structure”

The international agenda for the management of migration is a form of “concourse structure,” assuming that it “is the product of individual subjects and, once created, provides a context for the further development of their subjectivity.”[21] The reference to the management of international migration is today part and parcel of state officials’ language and discourses. In a document of the International Organization for Migration (IOM), it is described as being based on a series of “common understandings outlining fundamental shared assumptions and principles [among state actors] underlying migration management.”[22] The agenda is also aimed at creating state-led mechanisms designed to “influence migration flows.”[23] However, its repeated reference implies much more than the capacity to influence migration flows.

Beyond their conflicting sovereign interests, countries of origin, transit, and destination share a common objective in the migration management agenda: introducing regulatory mechanisms buttressing their position as legitimate managers of the mobility of their nationals and foreigners. The dramatic increase in the number of agreements linked to readmission cannot be isolated from the consolidation of this agenda, at the regional and international levels.

The international agenda for the management of migration has gained momentum through the organization of state-led international consultations in various regions of the world. Such regular consultations, or regional consultative processes (RCPs),[24] were critical in opening regular channels of communication among the representatives of countries of destination, of transit, and of origin. Scholars have already analyzed the ways in which RCPs can be referred to as networks of socialization[25] or “informal policy networks”[26] between state representatives, establishing connections and relationships and defining roles and behaviors.

At the same time, RCPs have contributed to defining common orientations and understandings[27] as to how the movement of all persons should be influenced and controlled. Through their repetition, they have instilled guiding principles which in turn have been erected as normative values shaping how international migration should best be administered, regulated, and understood.

In addition to their recurrence, such intergovernmental consultations have gradually introduced a new lexicon including such words and notions as predictability, sustainability, orderliness, interoperability, harmonization, root causes, comprehensiveness, illegal migration, prevention, shared responsibility, joint ownership, balanced approach, and temporariness. There is no question that this lexicon, endorsed and used by governmental and intergovernmental agencies, among others, has achieved a terminological hegemony in today’s official discourses and rhetoric as applied to international migration. It has also been critical in manufacturing a top-down framework of understanding while reinforcing, at the same time, the managerial centrality of the state and of its law enforcement bureaucracy.

This has had various implications. Perhaps the most important one lies in having built a hierarchy of priorities aimed at best achieving the objectives set out in the migration management agenda. The above lexicon was of course a prerequisite to giving sense to this hierarchy of priorities, for its main function is to delineate the contours of the issues which should be tackled first and foremost. As Robert Cox would put it, this hierarchy of priorities has gradually mystified the accountability of states through a process of consensus formation leading to the identification of top priorities and “perceived exigencies” while hiding others.[28]

The cooperation on readmission is perhaps the most symptomatic feature of this process of consensus formation and “shared problem perceptions”.[29] Today, it stands high in the hierarchy of priorities set by countries of destination, transit, and origin, whether they are poor or rich, large or small, democratically organized or totalitarian.

Readmission or removal has become a mundane technique to combat unauthorized migration and to address the removal of rejected asylum seekers. It is important to stress that cooperating on readmission does not only allow states to show they have the credible ability to prevent or respond to uncertainties, as mentioned earlier. It has also contributed, by the same token, to making their constituencies (more) aware of the presence of the sovereign within a specific territorial entity. In other words, keeping out the undesirables is not only a question of immigration control and the security agenda. It is also an issue closely linked with the expression of state authority and sanction, or rather with states’ capacity of classifying aliens and citizens alike, as well as their rights and position in a territorialized society.[30] In this respect, William Walters asks whether “the gradual strengthening of the citizen-territory link [has] less to do with any positive right of the citizen to inhabit a particular land, and more to do with the acquisition by states of a technical capacity (border controls, and so on) to refuse entry to non-citizens and undesirables.”[31]

Actually, the role of the state in protecting its citizens and in defending their rights and privileges has been linked with its capacity to secure its borders and to regulate migration flows. In a similar vein, the mass arrivals of unauthorized migrants, including potential asylum-seekers, has been interpreted as a threat to the integrity of the immigration and asylum systems in most Western countries. Most importantly, the use of such notions as “mixed flows,” “asylum shopping,” “bogus asylum-seekers,” “unwanted migrants,” “burden,” and “safe third countries” have started to shape more intensively public discourses, as well as the actions of governmental institutions, while implicitly depicting a negative perception of the claims of migrants and foreigners in general. Michael Collyer aptly explains how the establishment of a “security paradigm”[32] around migration has gradually consolidated a dominant discourse as applied to aliens, particularly undocumented migrants, who are referred to as invisible threats “who are to be found not in society but on the state’s territory.”[33]

There can be no question that the consolidation of a security paradigm has contributed to favoring the adoption of measures prioritizing the superior need to respond to perceived threats. This prioritization process, as shown by George Joffé, has led to the “implicit abandonment of the normative pressure for democratization and human rights observance among partner-states”[34] that was initially enshrined in the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership (EMP).

Restrictive laws regarding the conditions of entry and residence of migrants, asylum-seekers, and refugees, the reinforced controls of the EU external borders, and the dramatic expansion of the web of detention centres in and out of the EU territory illustrate the community of interests shared by countries of destination, transit, and origin.

This prioritization process has led to the flexible reinterpretation, if not serious breach, of internationally recognized standards and norms. The most emblematic case is perhaps the way in which the Italian-Libyan cooperation on readmission has developed over the last five years (see Silja Klepp’s chapter). In April 2005, the European Parliament (EP) voted on a resolution stating that the “Italian authorities have failed to meet their international obligations by not ensuring that the lives of the people expelled by them [to Libya] are not threatened in their countries of origin.”[35] This resolution was adopted following the action of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and various human rights associations denouncing the collective expulsions of asylum-seekers to Libya that Italy organized between October 2004 and March 2006 (see Emanuela Paoletti’s chapter for further details about the collective expulsions).

A few years later, neither the April 2005 EP resolution, nor the intense advocacy work of migrant-aid associations, nor the action of the office of the UNHCR, have contributed to substantially reversing the trend. To the contrary, Italy has broadened and reinforced its bilateral cooperation with Libya in the field of readmission, raising serious concerns among human rights organizations and the UN institutions regarding the respect of the non-refoulement principle enshrined in international refugee standards, on the one hand, and the safety of the readmitted persons to Libya, on the other.

The reinforcement of the bilateral cooperation became perceptible in May 2009 when Italy set out to intercept migrants in international waters before they could reach the Italian coasts to subsequently force them back to Libya. Hundreds of would-be immigrants and asylum-seekers have been forcibly subjected to these operations. In September 2009, Human Rights Watch (HRW) published a detailed report[36] on the dreadful conditions and ill-treatment facing readmitted persons in Libya. Despite the ill-treatment evidenced in the HRW report, the European Council called on the then-Swedish Presidency of the European Union and “the European Commission to intensify the dialogue with Libya on managing migration and responding to illegal immigration, including cooperation at sea, border control and readmission [while underlining] the importance of readmission agreements as a tool for combating illegal immigration.”[37] This intensified dialogue has become part of the geographical priorities of the EU external relations listed in the December 2009 Stockholm program.[38]

The above case study shows that the need to respond to perceived threats does not only rest on operable means of implementation that are often antonymous to transparency and to the respect of international commitments. It also rests on the subtle denial of moral principles or perhaps on their inadequacy to judge what is right and wrong. Clearly, such a denial does not stem from the ignorance or failure to recognize the value of international norms relating to migrants’ rights, asylum-seekers, and the status of refugees. Rather, it stemmed first and foremost from the prioritization of operable means of implementation at all costs. In this respect, the interview made by HRW with Frontex[39] deputy executive director, Gil Arias Fernández, is telling:

Based on our statistics, we are able to say that the agreements [between Libya and Italy] have had a positive impact. On the humanitarian level, fewer lives have been put at risk, due to fewer departures. But our agency [i.e., Frontex] does not have the ability to confirm if the right to request asylum as well as other human rights are being respected in Libya.[40]

The most eloquent aspect of Arias Fernández’s statement lies perhaps in the subjective vision that the border has to be controlled in order to save the lives of those migrants seeking better living conditions in destination countries. The bilateral cooperation on readmission is viewed as the best solution to tackle the “humanitarian” crisis, regardless of whether the country where migrants are to be readmitted (i.e., Libya) already possesses the capacity to fully respect the fundamental human rights and the dignity of the removed persons. This declaratory statement induces us to understand that it is because of the right to protect life that power is exercised and rhetorically justified by the same token.

This subtle denial and its ensuing operable means of implementation have gradually contributed to diluting international norms and standards which had been viewed as being sound and secure.[41] It is reflective of the conflicting relationships between national interests and international commitments in which the removal of aliens is embedded. Lena Skoglund observed the same tension with reference to diplomatic assurances against torture whereby a state (e.g., a country of origin) promises that it will not torture or mistreat a removed person viewed as a security threat by the law-enforcement authorities of another state (e.g., a host country).[42]

The predominant search for operability does not only undermine human rights law. It may also alter the understanding of the notion of effectiveness. What is effective has become first and foremost operable, but not necessarily in full compliance with international standards. In this volume, Emanuela Paoletti clearly shows that, over the last few years, operability has become a top priority for Italy in its bilateral cooperation on readmission with Libya.

A Self-Fulfilling System of Reference

The existence of a concourse structure, added to the consolidation of a security paradigm and its ensuing hierarchy of priorities constitute additional conditions fostering the expansion of the web of agreements linked to readmission. Of course, the use of the abovementioned lexicon has been instrumental in translating the need to cooperate on readmission into a top priority. Selfish relative gains could be overcome by the collective belief in common priorities allowing the centrality of the state to be buttressed.

At the same time, the mobilization of a technical expertise has played a key role in sustaining dominant schemes of interpretation as applied to international migration while legitimizing the prioritization of operable and cost-effective means of implementation in the field of readmission. The state has been but one actor in the consolidation process of the concourse structure described above. Through the selective allocation of public funds, some private think tanks have been subcontracted to deliver a technical expertise legitimizing a “form” of top-down knowledge about international migration and, above all, uncritically consolidating states’ hierarchy of priorities. Today, the production of knowledge about migration issues has become strategic, if not crucial, in political terms. By obstructing any alternative interpretation of a given problem, the production of a private expertise does not only pave the way for dealing with the problem, but it also strays from the cause of the problem and subtly justifies a unique technical solution as the lesser evil. Moreover, the emergence of a private technical expertise has contributed to the production of a dominant scheme of interpretation about the current challenges linked with the movement of people by serving policy-makers’ priorities without questioning their orientations.

Similarly, in the fields of the fight against unauthorized migration, detention, and readmission, private business concerns and large security corporations ave been increasingly mobilized to arguably minimize the costs (and visibility) of removal and to maximize its operability. In this respect, Thomas Gammeltoft-Hansen explains that:

Today, the privatisation of migration control is far from limited to airlines or other transport companies. From the use of private contractors to run immigration detention facilities and enforce returns and the use of private search officers both at the border and at offshore control zones, to increasing market for visa facilitation agents, privatised migration control is both expanding and taking new forms.[43]

The outsourcing of migration controls to private contractors and multinational corporations (MNCs) in the security and surveillance sectors (e.g., EADS, Finmeccanica, Sagem Sécurité, G4S, Geo Group, to mention just a few) has gained momentum over the last ten years or so as a result of an amazingly lucrative business.[44]

Reasons accounting for the privatization and delegation of some regulatory functions of the state are diverse. In a recent study, Michael Flynn and Cecilia Cannon show that large security companies have penetrated national migration control and surveillance systems in a number of countries around the globe, whether these are countries of destination or of origin, not only because they are purportedly responsive to cost-effectiveness, but also because their involvement enhances states’ ability to respond quickly and flexibly to uncertainties and shocks.[45] The mobilization of private contractors does not question the managerial centrality of the state analyzed above; above all when considering that “the state in most instances retains close managerial powers or behavioral influence in terms of how privatized migration control is enacted and carried out.”[46] What stands out, however, is the evidenced lobbying and leverage capacity that MNCs can use to shape policy-makers’ perceived exigencies[47] as well as those of the public opinion. While being influential though not predominant in national systems, MNCs remain “masterless” in global systems, as Bruce Mazlish incisively wrote: “it is especially in the latter realm [i.e., the global systems] that our new Leviathans are most powerful.”[48]

It could even be argued that a self-fulfilling system of reference is emerging whereby the interests of the private remain intertwined with those of the public to respond and legitimize the abovementioned hierarchy of priorities and its operable means of implementation. Incidentally, private security companies and MNCs do not only deliver a service which, being private, often remains beyond public purview, they are also proactive in developing “extremely close ties”[49] with decision-makers and government officials and in expanding strategic alliances with other key private actors or subcontractors. Clearly, further evidence is needed to understand the actual impact of these interconnections on policy options and priorities. There are forms of interference that neither affect decision-making processes and policy options, nor are they meant to do so substantially. However, some may entail the provision of information that policymakers value in their day-to-day tasks. Information provision, which often takes place through special advisory committees, also implies how policy issues and exigencies can be perceived and dealt with. It is reasonable to assume that the participation of private contractors’ staff in such committees, as evidenced by Ben Hayes (2009), may have contributed to consolidating the hierarchy of priorities mentioned above and its security paradigm, while making its means of implementation if not more practicable, at least more banal, thinkable, and acceptable.

Conclusion

To understand where the significant increase in the number of cooperative agreements linked to readmission (whether standard or not) concluded between European and non-European countries lies today, one is obliged to take into consideration a series of cumulative factors. I explained how material and immaterial incentives, as well as migration salience, geographical proximity and changed power relations constitute key factors shaping states’ variable capacities to deal with readmission. Additionally, the need for flexible arrangements, which are in some cases more a necessity than an option, has gradually led to the emergence of diverse cooperative patterns on readmission. It is precisely the combination of these factors that has been conducive to the expansion of the web of agreements linked to readmission.

At the same time, the consolidation of a dominant scheme of understanding as applied to the management of international migration has undeniably contributed to reifying the centrality of the state while legitimizing its modes of interventionism, its policy options, and a hierarchy of priorities. Without the existence of an unquestioned scheme of understanding or doxa, based on the use of hegemonic language and sustained by the repetition of regional consultative meetings (mobilizing state actors from countries of origin, of transit, and of destination), neither the unbalanced reciprocities inherent in the cooperation on readmission would have become less critical in the bargaining process, nor would the web of agreements have developed simultaneously at the global level.

Saying that readmission is weaving its way through various policy areas only partly explains the reasons for which it has continued to stand high in states’ current hierarchy of priorities. Its prioritization is arguably linked with the growing awareness shared by all countries of migration that it allows their coercive regulatory capacity to be expressed when needed. For it not only categorizes, by means of legal provisions, the desirable and useful aliens, on the one hand, and the undesirable and disposable aliens, on the other, but also redefines the contours of a taken-for-granted sense of belonging and identity.

It is under these circumstances fraught with dominant subjectivities and commonplace ideas that the cooperation on readmission has been branded as the only technical solution able “to combat illegal migration.” It has been presented as a lesser evil able to tackle a common international challenge or threat while making states perhaps less careful about their own relative gains in the cooperation on readmission and undeniably far less sensitive to the reasons for which those who are viewed as illegal or undesirable left their homeland, let alone their dreadful conditions. Hannah Arendt wrote, with reference to some of the darkest times of Europe’s recent history, that “acceptance of lesser evils is consciously used in conditioning the government officials as well as the population at large to the acceptance of evil as such.”[50] I would add to Arendt’s argument that the reference to a lesser evil fosters consensus formation beyond national interests and subtly justifies, by the same token, the use of operable means that might weaken the enforceability of universal norms and standards on human rights without necessarily ignoring or denying their existence. In other words, the acceptance of the lesser evil filters and shapes our categories of thought. The Italian-Libyan pattern of cooperation on readmission, on which the authors focus extensively in this volume, is perhaps the most emblematic case.

It is against this background that the cooperation on readmission, as it stands now in international interaction, involves more than an absolute duty to re-accept one’s own nationals or a mere administrative device.

When faced with these conditions, one is entitled to wonder whether it is still reasonable to wallow in the denunciation of some states’ failure to fully respect their international commitments regarding the rights and human dignity of readmitted persons. To be sure, naming offenders is crucial. However, abuse and violations have become so glaringly obvious and arrogantly justifiable through the lens of the “lesser evil” that their public denunciation might lead to no concrete change, if not to the paradoxical acceptance of things as they are (“we cannot do otherwise”). Together with the denunciation of repeated violations, a thorough examination of dominant schemes of interpretation has to be provided in order to instill in the minds of officials and constituencies alike a sense of doubt and skepticism about the lesser evil and the drive for operability. This is what the authors set out to do by investigating what is really happening on the ground. In sum, the point is to understand.

[1]. Guy Goodwin-Gill, International Law and the Movement of Persons between States (Oxford: Clarendon, 1978), p. 201, cited in W. Walters, “Deportation, Expulsion, and the International Police of Aliens,” Citizenship Studies, Vol. 6, No. 3 (2002), pp. 265-292. See also Guy Goodwin-Gill and Jane McAdam, The Refugee in International Law, Third Edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

[2]. Kay Hailbronner, Readmission Agreements and the Obligation of States under Public International Law to Readmit their Own and Foreign Nationals, Zeitschrift für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht, No. 57 (1997), http://www.hjil.de/57_1997/57_1997_1_a_1_50.pdf.

[3]. Aristide Zolberg, A Nation by Design: Immigration Policy in the Fashioning of America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006), pp. 225-226.

[4]. Jean-Pierre Cassarino, “Informalising Readmission Agreements in the EU Neighbourhood,” The International Spectator, Vol. 42, No. 2 (2007), p. 182.

[5]. Charles Lipson, “Why are Some International Agreements Informal?” International Organization, Vol. 45, No. 4 (1991), pp. 495-538; Robert. O. Keohane, “Reciprocity in International Relations,” International Organization, Vol. 40, No. 1 (1986), pp. 1-27.

[6]. Readers will certainly note that the word “return” is not used in this volume as a synonym for readmission or removal, for it is viewed as being not only semantically misleading but also analytically biased. The use of “readmission” and “removal” is deliberate; it reflects the need for a critical approach to the current so-called “return policies” adopted by most EU Member States. These policies are primarily aimed at securing the effective departure of unauthorized aliens. In other words, they do not view return as a stage in the migration cycle. Nor do they consider reintegration. Although these policies are euphemistically named “return policies,” they prioritize the removal of aliens out of the territory of destination countries, with or without explicit coercion, to another country which is not necessarily aliens’ country of origin.

[7]. Barbara Koremenos, “Contracting around International Uncertainty,” American Political Science Review, Vol. 99, No. 4 (2005), p. 551.

[8]. Cassarino, “Informalising Readmission Agreements in the EU Neighbourhood,” pp. 179-196. See also Jean-Pierre Cassarino, “The Co-operation on Readmission and Enforced Return in the African-European Context,” in Marie Trémolières, ed., Regional Challenges of West African Migration: African and European perspectives (Paris: OECD, 2009), pp. 49-72.

[9]. Jean-Marie Henckaerts, Mass Expulsion in Modern International Law and Practice, (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1995); Kay Hailbronner, Readmission Agreements and the Obligation of States under Public International Law to Readmit their Own and Foreign Nationals; Bruno Nascimbene, “Relazioni esterne e accordi di riammissione” in Luigi Daniele, ed., Le relazioni esterne dell’Unione Europea nel nuovo millennio (Milan: Giuffrè editore, 2001), pp. 291-310; Martin Schieffer, “Community Readmission Agreements with Third Countries — Objectives, Substance and Current State of Negotiations,” European Journal of Migration and Law Vol. 5 (2003), pp. 343-357; Gregor Noll, “Readmission Agreements” in Matthew J. Gibney and Randall Hansen, eds., Immigration and Asylum: From 1900 to present, Vol. 2 (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2005), pp. 495-497; Annabelle Roig and Thomas Huddleston, “EC Readmission Agreements: A Re-evaluation of the Political Impasse,” European Journal of Migration and Law Vol. 9 (2007), pp. 363-387; Florian Trauner and Imke Kruse, EC Visa Facilitation and Readmission Agreements: Implementing a New EU Security Approach in the Neighbourhood, CEPS Working Document No. 290 (Brussels: Center for European Policy Studies, 2008); Nils Coleman, European Readmission Policy: Third Country Interests and Refugee Rights (Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2009); Bjartmar Freyr Arnarsson, Readmission Agreements: Evidence and prime concern, Master Thesis in International Law (Lund: University of Lund, Faculty of Law, 2007).

[10]. Arnarsson, Readmission Agreements: Evidence and Prime Concern.

[11]. El Arbi Mrabet, “Readmission agreements: The Case of Morocco,” European Journal of Migration and Law, Vol. 5 (2003), pp. 379-385.

[12]. The first G14 meeting took place in L’Aquila (Italy) in July 2009. The G14 comprises the world’s most wealthy and industrialized countries (G8) plus the G5, i.e., the group of emerging economies (Brazil, China, India, Mexico, and South Africa), and Egypt.

[13]. Cassarino, “Informalising Readmission Agreements in the EU Neighbourhood.”

[14]. Koremenos, “Contracting around International Uncertainty,” p. 562.

[15]. Cassarino, “Informalising Readmission Agreements in the EU Neighbourhood.”

[16]. Trauner and Kruse, EC Visa Facilitation and Readmission Agreements: Implementing a New EU Security Approach in the Neighbourhood.

[17]. For the sake of clarity, Graph 2 does not plot the numerous readmission agreements that have been concluded over the last decades, at a bilateral level, between the 27 EU Member States, Switzerland, Iceland, and Norway. Nor does it plot the growing number of agreements linked to readmission that third countries have concluded among themselves. Finally, Finland is not reported on Graph 2, for it has no known agreement linked to readmission with any third country, although Finland does practice readmission.

[18]. Duncan Snidal, “Relative Gains and the Pattern of International Cooperation,” American Political Science Association, Vol. 85, No. 3 (1991), p. 703.

[19]. John S. Dryzek, Margaret. L. Clark, and Garry McKenzie, “Subject and System in International Interaction,” International Organization, Vol. 43, No. 3 (1989), p. 475.

[20]. Dryzek, Clark, and McKenzie, “Subject and System in International Interaction.”

[21]. Dryzek, Clark, and McKenzie, “Subject and System in International Interaction,” p. 502.

[22]. “International Agenda for Migration Management: Common Understandings and Effective Practices for a Planned, Balanced, and Comprehensive Approach to the Management of Migration” (Berne: International Organization for Migration, 2004), http://apmrn.anu.edu.au/publications/IOM%20Berne.doc.

[23]. John Salt, Towards a Migration Management Strategy (2000), p. 11; Report based on the Proceedings of the Seminar on “Managing Migration in the Wider Europe,” Strasbourg, October 12-13, 1998 (Strasbourg: Council of Europe, 1998).

[24]. “While the first RCP was established in 1985, the majority of RCPs have emerged since 1995, often as a result of specific events or developments — for example, the fall of the Soviet Union, sudden major influxes of irregular migrants, and concerns over security linked to the events of 9/11” (IOM, source: http://www.iom.int/jahia/Jahia/regional-consultative-processes, accessed 10 December 2009). Major RCPs on migration include, among many others, the 2001 Berne Initiative, the 1991 Budapest Process, the 1996 Puebla Process, the 2002 5+5 dialogue on migration in the Mediterranean, the 2003 Mediterranean transit migration dialogue, the 2000 Migration Dialogue for West Africa, and the Global Forum on Migration and Development.

[25]. Colleen Thouez and Frédérique Channac, “Shaping International Migration Policy: The role of regional consultative processes,” West European Politics, Vol. 29, No. 2 (2006), p. 384.

[26]. Sandra Lavenex, “A Governance Perspective on the European Neighbourhood Policy: Integration beyond conditionality?”, Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 15, No. 6 (2008), p. 940.

[27]. Amanda Klekowski von Koppenfels, “The Role of Regional Consultative Processes in Managing International Migration,” IOM Migration Research Series No. 3 (Geneva: IOM, 2001), p. 24.

[28]. Robert W. Cox, “Problems of Power and Knowledge in a Changing World Order” in Richard Stubbs and Geoffrey R.D. Underhill, eds., Political Economy and the Changing World Order (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. 39-50.

[29]. Sandra Lavenex and Nicole Wichmann, “The External Governance of EU Internal Security,” Journal of European Integration, Vol. 31, No. 1 (2009), p. 98.

[30]. Godfried Engbersen, “Irregular Migration, Criminality and the State” in Willem Schinkel, ed., Globalization and the State: Sociological Perspectives on the State of the State (Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2009), pp. 166-167.

[31]. William Walters, “Deportation, Expulsion, and the International Police of Aliens,” Citizenship Studies, Vol. 6, No. 3 (2002), p. 267.

[32]. Michael Collyer, “Migrants, Migration and the Security Paradigm: Constraints and Opportunities” in Frederic Volpi, ed., Transnational Islam and Regional Security: Cooperation and Diversity between Europe and North Africa (London: Routledge, 2008), p. 121.

[33]. Collyer, “Migrants, Migration and the Security Paradigm: Constraints and Opportunities,” p. 130.

[34]. George Joffé, “The European Union, Democracy and Counter-Terrorism in the Maghreb,” Journal of Common Market Studies, Vol. 46, No. 1 (2008), p. 166.

[35]. European Parliament, European Parliament Resolution on Lampedusa, April 14, 2005, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do;jsessionid=8B5BEAAD5A3946….

[36]. Human Rights Watch, Pushed Back Pushed Around: Italy’s Forced Return of Boat Migrants and Asylum Seekers, Libya’s Mistreatment of Migrants and Asylum Seekers (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2009).

[37]. European Council (2009a) Brussels European Council October 29-30, 2009 Presidency Conclusions, December 1, 2009, p. 12, http://www.consilium.europocs/cms_dataa.eu/ued /docs/pressdata/en/ec/110889.pdf.

[38]. European Council, “The Stockholm Programme — An open and secure Europe serving and protecting the citizens,” December 2, 2009, http://www.se2009.eu/polopoly_fs/1.26419!menu/standard/file/Klar_Stockh….

[39]. Frontex stands for the European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of the Member States of the European Union, http://www.frontex.europa.eu/.

[40]. Human Rights Watch, Pushed Back Pushed Around: Italy’s Forced Return of Boat Migrants and Asylum Seekers, Libya’s Mistreatment of Migrants and Asylum Seekers (2009), p. 37.

[41]. Ruth Weinzierl, The Demands of Human and EU Fundamental Rights for the Protection of the European Union’s External Borders (Berlin: German Institute for Human Rights, 2007).

[42]. Lena Skoglund, “Diplomatic Assurances Against Torture — An Effective Strategy?” Nordic Journal of International Law, Vol. 77 (2008), p. 363.

[43]. Thomas Gammeltoft-Hansen, Access to Asylum: International Refugee Law and the Offshoring and Outsourcing of Migration Control (Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2009), p. 233.

[44]. Ben Hayes, NeoConOpticon: The EU Security-Industrial Complex (Amsterdam: The Transnational Institute, 2009), p. 12.

[45]. Michael Flynn and Cecilia Cannon, The Privatization of Immigration Detention: Towards a Global View, Global Detention Project Working Paper (Geneva: The Graduate Institute, 2009).

[46]. Gammeltoft-Hansen, Access to Asylum: International Refugee Law and the Offshoring and Outsourcing of Migration Control, p. 236.

[47]. Hayes, NeoConOpticon: The EU Security-Industrial Complex.

[48]. Bruce Mazlish, The New Global History (London: Routledge, 2006), p. 37.

[49]. Flynn and Cannon, The Privatization of Immigration Detention: Towards a Global View, p. 16.

[50]. Hannah Arendt, Responsibility and Judgment [ed. by Jerome Kohn] (New York: Schoken Books, 2003), pp. 36-37.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.