This essay is part of a series that explores the threat posed by the Islamic State (IS) to Asia and efforts that the governments of the region have taken and could/should take to respond to it. Read More ...

Counterterrorism strategies can be made more effective by incorporating deradicalization and rehabilitation measures. Deradicalization is a key element of Malaysia’s counterterrorism and violent extremism strategy. Malaysia’s initiatives in this regard are aimed at addressing the problem of radicalism due to religious misconceptions, with the specific purpose of rehabilitating and subsequently reintegrating militant detainees into society.

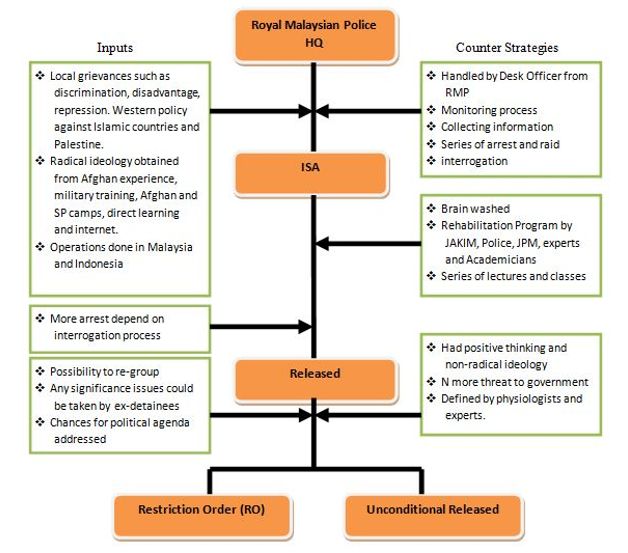

Malaysia’s main deradicalization initiative is the Religious Rehabilitation Program, which is based on reeducation and rehabilitation — the former focused on correcting militants’ political and religious misconceptions, and the latter on thorough monitoring of militant detainees after their release.[1] Family members of the detainees are engaged in the process; and are supported financially while the militants are held in detention. Subsequent to their release, militants are assisted in reintegrating into society. [Figure 1 depicts the Malaysian Government’s multi-stage deradicalization process.]

Figure 1. Malaysia’s Deradicalization Process[2]

As illustrated above, the Royal Malaysian Police (PDRM) is the main party responsible for deradicalization programs. The process was initially guided by the Internal Security Act (1960), which was later replaced by the Prevention of Crime Act (POCA) and Prevention of Terrorism Act (POTA) — the latter emerging as a direct response to the rise of Islamic State (IS).

Upon arrest, detainees are taken to the Special Branch Department (RMP) at Bukit Aman, Kuala Lumpur for interrogation and ordered detained. Depending on the information given by detainees, more arrests may be made at this stage. Detainees are put under Restriction Order (RO) after being released, though some are released unconditionally. The Malaysian authorities have also implemented counter strategies, which rely on cooperation between the RMP, the Prime Minister’s Department, the Department of Islamic Development Malaysia, and many others.[3]

Malaysian authorities consider rehabilitation to be the most important tool in countering radicalism. They have employed a religious approach to rehabilitation as a means of tackling what they regard as being the root of the problem. The rehabilitation program, which is conducted by the federal Department of Islamic Development Malaysia (JAKIM), involves counselling, whereby detainees are helped to explore and detect their misinterpretations of Islam. Experts in this area such as Ustazs and Ulama are invited to clarify the aspects of religious doctrine and the belief system that detainees have misconstrued.[4] At the end of the program, the radical ideology based on salafi-wahhabism thinking will have been replaced by more accurate Islamic teachings, especially regarding the real meaning and idea of jihad.

The rehabilitation process is divided into four stages. In the first stage, counsellors from JAKIM and the police extricate any negative ideology or twisted Islamic perceptions. Next, counsellors play their role in commencing discussions with detainees and addressing their ideological misconceptions. At this point, every counsellor faces a challenging task, as the militants try to defend their misguided perspectives. Counsellors must counter these efforts by demonstrating clear and deep knowledge of Islam. In the third stage, all twisted Islamic concepts and ideologies are replaced with the correct interpretations of the Qur’an and Sunnah. After all of these steps are completed, more comprehensive education about Islam begins.[5]

In addition conducting the rehabilitation process for detainees, the Malaysian government also engages the detainees’ family members in order to break the cycle of indoctrination and to prevent the further spread of radical ideology. Usually, detainees’ family members are in a state of shock, not quite understanding what has transpired. Financial support to the families of detainees undergoing rehabilitation is intended both to help sustain them and to convey a positive impression of the purpose of the deradicalization initative. Other government agencies, such as Jabatan Kebajikan Masyarakat (the Social Welfare Department) and Pusat Zakat (the State Alms Centre), assist in mobilizing funds for detainees’ families.

Malaysia’s deradicalization and rehabilitation efforts have proved to be effective, as exemplified by the ‘recovery’ of ex-prisoners such as Ahmad Wan Ismail and Suhaimi Mokhtar.[6] According to former PDRM Special Branch Director, Datuk Seri Muhammad Fuzi Harun, these programs have achieved a 95% success rate, and have been very effective in combating terrorist violence in Malaysia.[7] He emphasized that the rehabilitation period must comply with legal provisions under the POCA and POTA in order to provide maximum opportunity for input from detainees and family members, thereby reducing the likelihood of relapse cases that could jeopardize the nation’s security.[8]

The Module for Deradicalization

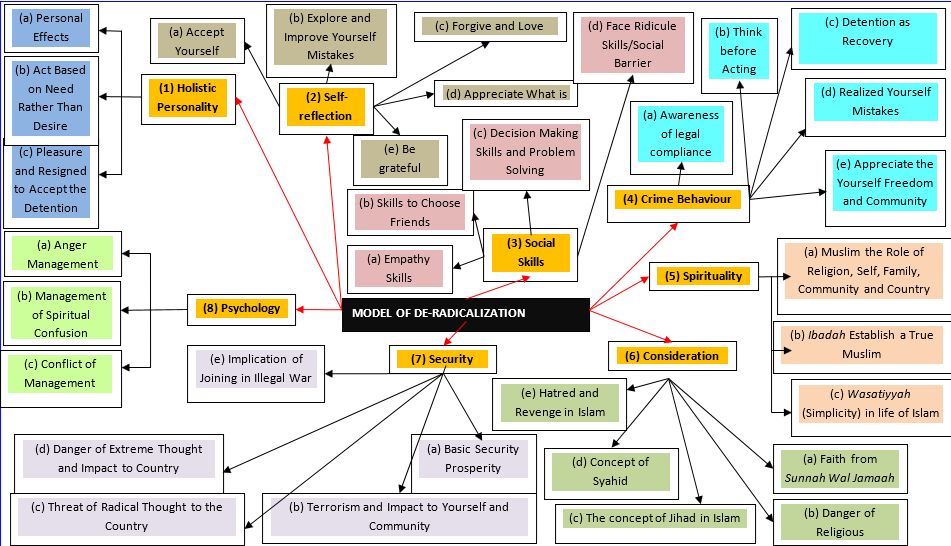

The module for deradicalization was launched with the intention of assisting the government in rehabilitating detained militants and in helping rebuild their personality. The module encompasses eight areas: holistic personality, self-reflection, social skills, crime behavior, spirituality, consideration, security, and psychology. [See Figure 2] Of these, Malaysia places emphasis on the spiritual component. Taken into consideration is the fact that the real meaning of concepts such as jihad, wasatiyyah (moderate) and akidah (faith) has been covered in the rehabilitation programs in prison and community-based engagements. This approach can be implemented in other countries as well.

Figure 2. The Module for Deradicalization

In 2016 the Ministry of Home Affairs formulated the Integrated Deradicalization Module for Detainees (or Pemulihan), which is a document whose contents are intended to serve as a guide for those agencies, officers and others charged with the task of rehabilitating militant detainees. Pemulihan is described as “a correctional rehabilitation special module intended to develop knowledge and behavioral skills through a set of programs delivered by advisors specialized in different areas of related sciences.”[9]

Administered by the Ministry of Home Affairs, in concert with the Prison Department of Malaysia and Royal Malaysia Police, the module consists of a suite of rehabilitation programs (e.g., psychological, social, history, art therapy, self-development as well as ‘Online Engagement’) offered over a two-year timeframe. On top of that, government also created voluntary program, conducted under the auspices of the Ministry of Home Affairs, this is a program where qualified scholars are hired to enter online chat rooms for holding discussions with users on Islam. This caters especially to those seeking religious knowledge and clarification, wherein, for example, they discuss the dangers of takfiri (apostasy) ideas.

The Malaysian government through this special rehabilitation program also worked closely with the Civil Society Organizations (CSO) to facilitate terrorist rehabilitation. They have rehabilitated and reintegrated hundreds of Syria and Iraq alumni as well as terrorism-related convicts.

The Pemulihan rehabilitation program consists of three main components: psychological rehabilitation, religious rehabilitation, and social rehabilitation. Throughout the detention period, detainees are visited regularly by psychologists who provide counselling and assess their ability to cope with mental stress. This allows psychologists to delve into the detainees’ psychological reasoning, and thereby assess their inclination for hatred and violence as well as susceptibility to radical influences. Trained psychologists are also involved in doing proper assessments of behavioral and cognitive aspects of the detainees’ progress during rehabilitation.

Insights from the Field

Malaysia’s experience with deradicalization and rehabilitation programs has revealed some promising pathways and has exposed some persistent obstacles to making further progress in combating violent extremism in Muslim societies.

First, the results have shown that in order to fight against terrorism, various methods should be applied and tailored to specific backgrounds and understandings of Islam among the Muslim population.

Second, interactions with militant detainee-participants in deradicalization and rehabilitation programs, including that of Malaysia, have demonstrated that the root causes of worldwide Muslim grievances have not been addressed. Military actions taken by the United States and Israel, for example, have been perceived by radical Muslims as a war against Islam and have stirred not just popular resentment but sparked vendettas.

Specifically within Southeast Asia, it is very difficult for any government to settle issues related to militant ideology and radicalism if they are unaware of or fail to understand the nature of underlying and deeply felt grievances. For example, radical Muslims in Southern Thailand clearly have no relation to terrorism; their struggle lies in an aspiration to reestablish the Malay-Pattani Kingdom. To generalize militant activities in Southeast Asia as being the same as militant activities in Afghanistan or the Middle East is simplistic because the roots of the struggle are different.

Third, it can be seen that work in the field of radical Islamism and religious terrorism in general suffer from a knowledge gap. Because the phenomenon of religious terrorism crosses a multitude of academic disciplines, it creates a challenge to academicians unaccustomed to collaborating. Furthermore, the distinctive perspectives and modes of research engaged in by scholars in each of those disciplines have led most to rely on familiar perspectives and long-established arguments that are prevalent in each field.

Fourth and related, in order to surmount this challenge, it is necessary to understand the core problems faced by Islamic communities. Among the crucial issues that should be taken into consideration by various parties is the curriculum of Islamic subjects being taught in schools and universities. The true meaning and exact concept of jihad as well as the broader understanding of jihad should be implemented to avoid misconceptions to take root and spread.

Fifth, clear distinctions should be drawn-out between moderate and extreme in understanding Islam. Muslims in moderate countries in the region, such as Malaysia, Indonesia and Brunei, have shown their ability to accept contemporary issues in their daily life without jeopardizing their beliefs, however for extremists, they will continuously refuse to tolerate in any condition. The majority of Muslims in this region hold moderate beliefs and wish for peace and harmony. Only a small fraction of Muslims are involved in terrorist activities. However, such activities carried out by these individuals tarnish the image of all Muslims and create misconceptions about the true nature of Islam.

Conclusion

Apart from facilitating the recovery and reintegration into mainstream society of militant detainees, deradicalization programs have the potential to reduce the further spread of militant propaganda, which poses a threat to social stability and national as well as international security. However, further improvement of existing deradicalization modules is necessary to ensure that former terrorist prisoners are imbued with patriotic loyalty and young people with whom they come into contact (especially family members) do not follow in their footsteps. Finally, sharing the experiences of former terrorist prisoners can play a valuable role in raising public awareness of the dangers that radicalism poses not just to society but also to the individuals and their families who are sucked into this retrograde culture.

[1] Saba Noor and Shagufta Hayat, “Deradicalization: Approaches & Models,” Pak Institute of Peace Studies (April 2009): 3, http://www.pakpips.com/web/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/116.pdf.

[2] Rohan Gunaratna, Terrorist Rehabilitation and Community Engagement in Souheast Asia (London: Routledge, 2019) 12-15.

[3] Mohd Mizan Aslam, The Threat of DAESH in Malaysian Higher Education Institutions (Kuala Lumpur: MyRISS Special Report to Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia, 2016) 30.

[4] Mohamed Bin Ali, Coping With the Threat of Jemaah Islamiyah (Singapore: Taman Bacaan Pemuda Pemudi Melayu Singapore, 2007) 108-115.

[5] Mohd Mizan Aslam, “The Threat of DAESH in Malaysian Higher Education Institutions,” in Alice Suriati Mazlan, Zuraidah Abd Manaf, and Mohd Mizan Mohammad Aslam (Eds.), Radicalism and Extremism: Selected Works (Putrajaya: Ministry of Higher Education, 2017) : 93-100, http://mycc.my/document/files/PDF%20Dokumen/Radicalism%20and%20Extremism%20Selected%20Works.pdf.

[6] Mohd Mizan Aslam and Rohan Gunaratna, Terrorist Rehabilitation and Community Engagement in Malaysia and Southeast Asia (London: Routledge, 2019).

[7] Laili Ismail, “Police: Msia’s deradicalisation programme has 95 per cent success rate,” New Straits Times, January 26, 2016, https://www.nst.com.my/news/2016/01/124116/police-msias-deradicalisation-programme-has-95-cent-success-rate.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Government of Malaysia, Ministry of Home Affairs, Integrated Deradicalization Module for Terrorists. 2nd ed. (Selangor: Percetakan Mesbah Sdn. Bhd., 2015).

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.