After more than two months of Saudi-mediated indirect talks between the Republic of Yemen Government (ROYG) and the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council (STC), a separatist political movement, the two sides finally reached a deal on Nov. 5. The Saudi effort, which culminated in the signing of the Riyadh Agreement, is aimed at resolving the conflict within the Arab coalition-backed front and uniting the two parties in the fight against the Iranian-backed Houthi militias. The agreement, which spans political, economic, security, and military arrangements, involves restructuring the executive, military, and security branches of the ROYG, partial disarmament of STC-loyal forces, and the demilitarization of Aden — all of which will be phased in over the next three months. But even as the deal presents an opportunity for de-escalation in the short term, it is likely to encounter significant hurdles within the 90-day implementation timeframe, as it is doubtful it will resolve the underlying causes of the confrontation, including the issue of secessionism.

Decoding the signals

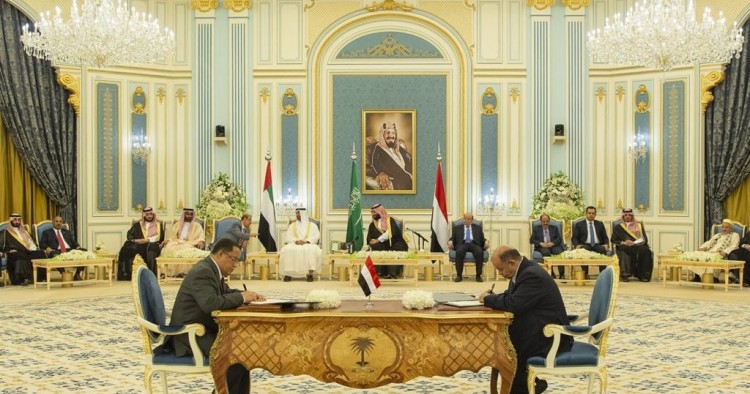

The official signing ceremony at al-Yamama Palace in Riyadh was rich with symbolism suggesting local actors will have difficulty moving forward with less regional involvement. First, it is clear that the Saudis are now in the driver’s seat, as Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s leading role in the ceremony illustrated. Although Riyadh has increased its leverage, bargaining power, and responsibility vis-à-vis the parties, the agreement will be a difficult test for Saudi Deputy Defense Minister Prince Khalid bin Salman, who holds the Yemen file.

Second, by inviting UAE Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed to the ceremony, whom the ROYG considered more of an enemy than a partner for “sponsoring” the STC’s “armed rebellion” and “counterbalancing militias,” Riyadh has indicated that while unifying the coalition front is important, its strategic partnership with Abu Dhabi is of far greater significance than its ties with President Abed Rabbo Mansour Hadi. But whether this engagement will pave the way for a Yemeni-Emirati rapprochement is as yet unclear.

The third message is local. That neither President Hadi nor Prime Minister Maeen Abdulmalik Saeed signed the agreement speaks volumes about the significance of the STC. Instead, it was Deputy Prime Minister Salem al-Khanbashi, from the eastern governorate of Hadramawt, who signed the deal on behalf of the ROYG, highlighting two competing southern aspirations: federalism and secessionism.

A perceived win-win, but in search of a southern godfather

On the surface, both parties consider the deal a victory. President Hadi’s chief of staff, Abdullah al-Alimi, described it as a “national formula that contained the rebellion crisis,” while STC Deputy Chairman Hani bin Braik called it “the gateway for salvation,” enabling them to re-focus on the Houthi threat. Both sides have valid points. While the agreement enables the ROYG to resume operations at state institutions in the interim capital, Aden, which STC-affiliated forces seized on Aug. 10, it also concedes the STC’s legitimacy as a player in Yemeni affairs, including the South.

Despite its political victory, the STC has not emerged from either the recent military escalation or the Riyadh Agreement as the godfather of southern affairs, nor is it considered the standard bearer of the secessionist cause. By engaging the southern Hirak, Hadramawt Conference, and other relevant southern entities in the 50:50 power-sharing government, President Hadi has pushed back against the STC’s claim of representing the South once again, defusing the southern question in the short term, and checking the STC to a degree. In essence, this balancing act is a risk minimization strategy that once again revives the three-decade-old question about secession: Can southern actors unify behind a single leadership?

The ROYG restructured

A power-sharing arrangement between the South and the North is itself nothing new. In 2014, the National Dialogue Conference (NDC) addressed southern grievances by devising a 50:50 power-sharing mechanism between the two regions. But what this arrangement now means is a reduction in the number of southern appointees in the ROYG from approximately 70 percent to 50 percent within 30 days, a move benefitting the northerners.

Therefore, the strategic objective of the August armed clashes, and by extension the Riyadh Agreement, isn’t sharing the executive branch but rather restructuring the ROYG and legitimizing the STC as a formal player in Yemeni affairs following the UAE military drawdown. Including the STC and reducing the number of cabinet ministers by nearly a third to a maximum of 24 means Islah influence will be partly curtailed and the ROYG’s performance is expected to improve.

To bring about deeper changes and reshape the local distribution of power, new governors and security chiefs for Aden, Abyan, and Dhale will be appointed within 30 days, followed by other southern governorates a month later. From a UAE perspective, the deal transforms the STC and its military affiliates from “UAE-backed militias” to a state actor across the political, security, and military domains — formalizing Abu Dhabi’s hand within the ROYG.

Reminiscent of the 2011 power-sharing deal between Yemeni political parties that later led to bureaucratic ineffectiveness and intra-government rivalry during a relatively peaceful political transition, the likelihood of forming a functioning and unified government remains slim unless current mistrust between local and regional parties is addressed, which is unlikely to happen.

Military and security challenges

The military and security arrangements outlined in the deal seem too ambitious to achieve within 90 days and are a huge responsibility for Riyadh to shoulder. Interestingly, the provisions transfer greater authority from the ROYG to the deal’s patron, Saudi Arabia, and by extension, the coalition, under which the UAE continues its counterterrorism campaign.

By collecting, storing, and centralizing the use of medium and heavy arms from STC-affiliated armed groups in Aden and not allowing the government to exercise legitimate control as outlined under UN Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 2216, the coalition merely reinforces the existing dynamic of subordination rather than partnership and minimizes the already limited autonomy of the Yemeni government.

Considering that without medium and heavy arms the STC wouldn’t have taken over Aden and achieved its current political objectives, its armed affiliates are unlikely to fully disarm as the STC will likely seek to maintain autonomous military capabilities. Deception and symbolic surrender, especially if the coalition covers up facts to claim success, are a possibility — and one with a precedent. On Aug. 17, the Arab Coalition Joint Forces Command indicated that the STC-affiliated forces had “started to withdraw and return to previous positions,” which was false and refuted by the STC’s Bin Braik.

The integration of UAE-backed forces loyal to the STC under the auspices of the ministries of defense and interior will likely be onerous for several reasons. First, virtual integration into the Yemeni forces represents a financial gain for the STC affiliates because it grants them wages while it conditions the prospects of re-escalation on the ability of the ROYG to pay salaries regularly. The current state of Yemen’s decrepit economy and its limited ability to generate revenue mean the integration could be a significant economic burden should the country fail to maximize oil exports and channel revenues from liberated territories to the Central Bank of Yemen (CBY) in Aden, including from its branch in Marib.

That said, this also presents an opportunity for the UAE to demonstrate goodwill, rebuild its image as a partner, and pave the way for rapprochement. Given that Abu Dhabi has financed the STC and its affiliates, it could choose to reduce Yemen’s economic burden by instead channeling such allocations to the CBY in Aden to pay the newly integrated forces.

Second, the full success of integration is contingent on three criteria: the extent to which Riyadh checks the influence of the STC’s sponsor, Abu Dhabi; whether the UAE will continue to finance the STC; and how the military and security regiments will be integrated.

If Prince Khalid bin Salman engages the STC leadership to reduce Abu Dhabi’s patronage and ensures UAE financial and military support is rerouted from the STC to the ROYG, the chances of integration crystallizing would be high. The method of integration will be crucial though. If STC-loyal forces are integrated into Yemen’s national military and security regiments as units and not as individuals, this could result in a re-escalation comparable to that of 1994, when civil war broke out between northern and southern forces.

The details of how integration will proceed are unclear and ultimately it will be at the discretion of the Saudis, should there be a dispute. Whether the perception that the Riyadh Agreement is a win-win for both sides will endure remains a question for the future. The issue of Aden may well test the Saudis’ will and intra-Yemeni trust building within the first several weeks.

The Houthis next

By concluding the Riyadh Agreement nearly a year after the Stockholm Agreement, the ROYG has normalized what it once considered a coup to strengthen its position in the southern governorates and remedy broken partnerships ahead of nationwide peace talks vis-à-vis the Houthis. With the prime minister set to return to Aden by Nov. 13, the idea that Sana’a is next seems unlikely on the military front, barring the outbreak of a popular revolution across the northern governorates like that of the late 1960s. For the Houthis, this deal sets a baseline for expectations. If the STC could achieve this much by taking over Aden, the Houthis’ demands will force the ROYG to make huge concessions far above and beyond UNSCR 2216. Despite all the hurdles, the Riyadh Agreement opens a window of opportunity for a nationwide peace agreement, especially as the Saudis reactivate backchannel talks with the Houthis, the international community increases its support for the UN special envoy to end the war, and neither the ROYG nor the Houthis has achieved an outright military victory.

Ibrahim Jalal is a non-resident scholar at MEI in the Gulf and Yemen Program. The views expressed in this article are his own.

Photo by BANDAR ALGALOUD/SAUDI KINGDOM COUNCIL/HANDOUT/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.