Amid a minor midsummer media frenzy about the Biden administration’s efforts to forge a normalization accord between Israel and Saudi Arabia, I reached out to several trusted contacts who offer smart, clinical, and informed analysis on this complicated region of the world and asked them for their take on what was happening and the prospects for progress toward a deal.

As one Saudi observer quipped to me, “Well, apart from having to convince the most right-wing government Israel has seen since its creation to accept the fact that Palestinians are human beings and get two-thirds of the U.S. Congress to agree to Saudi Arabia’s security requests, the rest should be easy.”

Forging a deal establishing open, normal bilateral ties between Saudi Arabia and Israel would be a major feat with plenty of potential perils along the way — the diplomatic equivalent of climbing Mount Everest. If done right, the result would be historic and transformative for the Middle East with positive geopolitical repercussions.

But like ascending Everest, the effort requires a lot of preparation, a clear roadmap, tools to monitor a volatile environment, and a team of experienced sherpas to execute the climb. Climb too quickly without the right tools, and you can find yourself in a perilous situation that could end in disaster. Come prepared with a clear game plan and the right team, and the odds of success improve.

Here are five factors to watch as the Biden administration continues its efforts to produce a major diplomatic breakthrough in the Middle East:

1. The health and stability of U.S.-Saudi bilateral ties. One important component of the discussions is linked to efforts to boost U.S.-Saudi ties in multiple areas, including security and civilian nuclear cooperation. The fact that these discussions are taking place alongside a broader set of issues that animate bilateral ties, including energy, economic cooperation, technology, and joint regional infrastructure efforts, is a positive sign that relations have improved from where they were at the start of the Biden administration. Credit is due to the Biden team for ignoring the considerable noise and rancor in America’s debate about Saudi Arabia and trying to put the bilateral relationship on a more stable foundation.

But the systemic mistrust between the two countries remains considerable, and the feeling is mutual. If the U.S.-Saudi relationship were a marriage, it would continue to be one in need of therapy, especially when one looks at the broader public and political debates taking place within the two countries about the other. Recent press reports indicate that the Biden team is discussing at least two hot button issues — arms sales and civilian nuclear cooperation — that have animated debates in Congress, with concerns expressed from both sides of the aisle about the advisability of deepening ties with Saudi Arabia. There’s a similar debate inside the Saudi kingdom about America’s strategic reliability, driven by years of discussions in the U.S. about pivoting away from the region and accelerated by a general passive response from the last three U.S. administrations to the serious security threats Saudi Arabia faces in its neighborhood.

Progress toward a U.S.-brokered deal between Israel and Saudi Arabia doesn’t require fixing all of the challenges in the U.S.-Saudi relationship, but it does necessitate a broader effort inside both countries to put the relationship on a more stable footing.

2. The health and stability of U.S.-Israeli bilateral ties. Another bilateral relationship suffering from a major trust deficit is the U.S.-Israeli one. Much of this is related to the personality and persona of Israel’s current prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu. He is viewed by many in the Biden administration and the Democratic Party, including many centrists, as untrustworthy and unreliable, someone who has tried to make the bilateral relationship a partisan wedge issue in U.S. politics.

However, the problem increasingly runs more deeply than just one individual leader. Concerns about the moves the current Israeli government has made and the strains they have imposed on its democracy have roiled already heated debates about America’s relationship with Israel, including among key constituencies like Jewish-American groups. Add to this some of the steps Israel has taken in the region or the world that were viewed as not in alignment with U.S. policies, including on key issues such as Russia’s war in Ukraine and China, and there are far more doubts in the relationship now than there ever were before.

Another key question is what the United States can do to disincentivize the current Israeli government from taking steps that undercut its existing relationships with others in the region. Recent moves by Israel in the West Bank and Jerusalem have slowed progress in deepening ties forged through the 2020 Abraham Accords, and that ultimately undercuts diplomatic efforts by the Biden administration to build on a key achievement of the Trump era.

3. The Palestinian factor. This third issue — Palestine — has all too often been pushed to the sidelines or dismissed as unimportant, but the lack of progress has bedeviled previous U.S. diplomatic efforts on the Arab-Israeli front for more than 40 years now. The simple fact that millions of Palestinians continue to live in limbo in the occupied territories or in the diaspora impedes progress toward creating a more stable, prosperous Middle East. “Normalization” accords that ignore the centrality of the Palestinians in this equation will have much more limited potential benefits.

This third factor is also probably the one that is the least developed. There are ongoing talks between Palestinians and Saudis, and the Biden administration has tried to adopt a more proactive stance in engaging the Palestinian Authority (PA) on a range of issues — in sharp contrast to the Trump administration’s approach of applying “maximum pressure” and isolating the PA, which didn’t produce positive results.

Saudi Arabia seems less likely to move as quickly as the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Morocco did in the Abraham Accords, for a range of reasons. First, it has made many unforced errors over the past five years in its own approach to the region, including in Yemen, Lebanon, and Qatar; and these mistakes have made Saudi regional foreign policy a bit more cautious, even if it remains assertive. Saudi Arabia cannot afford the risks of making moves without substantial progress on the Palestinian front, risks that include dissent from within and strong criticism from other leading Arab and Muslim-majority countries that look to Riyadh as a leader. Second, Saudi Arabia is concerned about potential blowback from retrograde, backward-looking regional actors like Iran and its proxy network of groups such as Lebanon’s Hezbollah.

4. Regional and broader geopolitical conditions. The broader Middle East is currently in a tenuous phase of countervailing trends, with some pointing to de-escalation and others raising concerns about broader instability, as outlined in a recent report released by the Middle East Institute. For example, Saudi Arabia and other countries like the UAE have taken steps to de-escalate tensions with Iran through diplomacy, even as Iran continues to take actions that undermine regional stability. Iran’s nuclear program also introduces more uncertainty and unpredictability in the region at a time when there are limited signs of diplomatic engagement with Iran bearing some results.

The broader geopolitical environment doesn’t appear as advantageous for peacemaking as it did during previous eras, either. When the big advances were made in the 1990s, it was done in the post-Cold War context, when the United States was seen by many as having no major strategic rivals after the collapse of the Soviet Union. That was then and this is now, with the global strategic landscape increasingly framed as one of competition between China, the United States, Russia, Europe, and a growing number of other rising powers.

2023 is not 1991 for America in the Middle East, meaning that it just didn’t win the Cold War and just didn’t win a quick war in the region, events that helped shaped the strategic context for some of the gains in the 1990s.

Neither the regional nor geopolitical conditions militate against progress on the Israel-Saudi front and, in some ways, the uncertainty of the strategic context may actually open up more opportunities. But the point in raising this fourth factor is to highlight that every diplomatic move on the Israel-Palestine-Saudi Arabia front should take into account the implications it has for other parts of the Middle East and the wider geopolitical context.

5. America’s political divisions and election calendar. Last but not least is the fifth factor of U.S. politics and the 2024 election calendar. According to some press reports, this aspect is motivating the supposed alacrity on the Israel-Saudi front, with some in Saudi Arabia thinking that it would be better to get a deal with a Democratic president and some in the Biden team thinking that engaging Israel and Saudi Arabia might blunt unhelpful efforts by political leaders in those two countries to make decisions that could undercut Biden’s re-election chances.

This fifth factor matters quite a lot, especially given the recent tendency in America’s politics to turn everything into a “red versus blue” issue. The tribalism and sectarianism in U.S. politics about foreign policy has made America its own worst enemy, as America’s adversaries and competitors seek to exploit these partisan divisions. Add to it the neo-Orientalism that has animated key parts of America’s discourse about the Middle East in recent years — the tendency to use the people and issues of the region as mere props in our own social and political debates — and that means there’s not a very favorable political environment for supporting progress.

The situation isn’t so bleak, however, as America has seen glimmers of trans-partisan efforts in response to Russia’s war against Ukraine and the challenges posed by China, and perhaps there is room to create new political coalitions at home to support a steadier U.S. hand in the Middle East. But the current state of the Republican Party, as well as the media and political landscape that encourages divisions, probably means that every move the Biden team makes on the fraught Middle East policy front will likely be used by some Republican leaders, especially those running for president, to divide rather than unite.

To be clear, nearly all Middle East policy issues are an elite political debate in today’s America, as most American voters aren’t interested in what’s happening in the region these days the way they once were in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks and the 2003 Iraq war.

Conclusion

This exposition is not intended to douse the diplomatic efforts with cold water or fan the flames of advocacy in support of any particular position, but rather it aims to provide a partial analytical ledger of factors to keep in mind as the administration works to push things forward on the Israeli-Palestinian-Saudi front over the next year.

Climbing this mountain would be an important strategic achievement for the region and the world, if it is done properly, with all of the right elements in place. The most important commodity is trust, not oil, and it is essential to not overpromise and underdeliver, as some have cautioned. Even though it’s clear that Israel and Saudi Arabia have had ongoing discussions on a range of issues, it is difficult to imagine the United States not playing a role in offering reassurances that help move things forward.

Two additional challenges for the Biden team in trying to devise a plan for progress on this front: First, the center of gravity in America’s debates over the next 16 months will largely be at home, as most Americans aren’t concerned about foreign policy issues, including the Middle East. Second, when it comes to foreign policy, the Biden administration faces some serious bandwidth issues as it seeks to support Ukraine, compete with China, address climate change, and link America’s new national industrial policy to measures in the world that build stronger relationships with partners and allies.

The effort to produce progress in Israeli-Saudi relations will likely take more time and energy to achieve lasting results and maximum benefits for the broader region and world — it is very much worth the effort, but only if it’s done right.

Brian Katulis is a senior fellow and vice president of policy at the Middle East Institute.

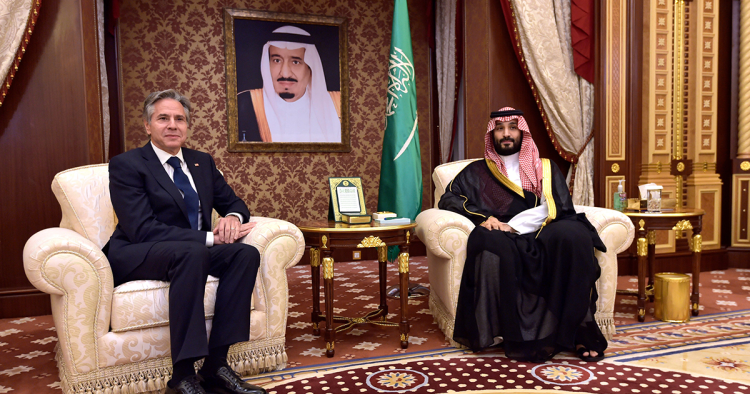

Photo by AMER HILABI/POOL/AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.