This article is part of a series that draws on the conclusions of a high-level workshop on economic diversification and the energy transition held on the sidelines of the American University of Kurdistan’s annual Middle East Peace and Security (MEPS) Forum in November 2022.

According to the latest report from the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the world has already warmed by around 1.1°C compared to pre-industrial times and will likely approach 1.5°C within the next two decades. Every corner of our planet has already experienced the impacts of climate change, from extreme heatwaves and floods to devastating droughts. According to the IPCC report, to avoid the catastrophic impacts of climate change, global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions will have to be cut by half by 2030 — relative to 2010 levels — and reach net zero around mid-century. To date, over 130 countries, covering 83% of global emissions, have acknowledged this urgency by committing to achieving such net-zero targets. These include five Gulf Arab states: Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.

The gap between where the world stands today and where it needs to be in 2050 is substantial, however. For instance, in a net-zero emissions pathway, the share of renewables in total electricity generation globally should increase from the current 29% to over 60% in 2030 and to nearly 90% in 2050. Similarly, clean hydrogen production should increase six times from the current levels of 0.87 million tons (Mt) to 530 Mt in 2050. Achieving these targets will require incremental increases in clean energy investments, approximately $2-4 trillion per annum between 2022 and 2030, roughly triple today's levels of $755 billion. Closing this gap will require collective efforts from both the developed and developing worlds, but the speed with which countries can close this gap will depend on many factors, including political will; availability of natural resources; institutional, financial, and technical capabilities; and readiness.

The Gulf Arab states, while major oil and gas producers, can play a significant role in supporting global efforts to close the gap and achieve net-zero goals. That is because the Gulf Arab states are not only endowed with great potential for renewable energy resources as well as some of the world’s lowest carbon content fuels, but also with, to varying extents, sizable financial resources. Yet, to unlock such huge potential, the Gulf Arab states will need to systematically identify and address the various challenges in their path to net zero.

The GCC’s net-zero technological mix and where countries stand today

Different organizations such as BP and the International Energy Agency (IEA) have published projections of energy supply and demand in a net-zero scenario, consistent with the objectives of the Paris Agreement to keep global warming within 1.5°C. BP’s 2020 net-zero scenario (suggesting a 15% decline in emissions by 2050 consistent with a 1°C rise in temperatures) and the IEA’s 2021 net-zero emissions (NZE) scenario (suggesting around a 40% decline in emissions in 2030 and to net zero in 2050 for global energy‐related and industrial process emissions) suggest a dramatic increase in the share of new and clean energy — including hydrogen, renewables, and nuclear — and a significant decline in that of hydrocarbons — coal, natural gas, and oil — in the future energy supply. Yet, in both scenarios, hydrocarbons will continue to play a role in meeting energy needs in a net-zero future, albeit a declining one. BP’s net-zero scenario suggests that the share of hydrocarbons will be between 20% and 70% by 2050. The IEA’s NZE posits that the share of fossil fuel will be just over 20% in 2050, falling from 72 million barrels per day (mbpd) in 2030 and to 24 mbpd in 2050.

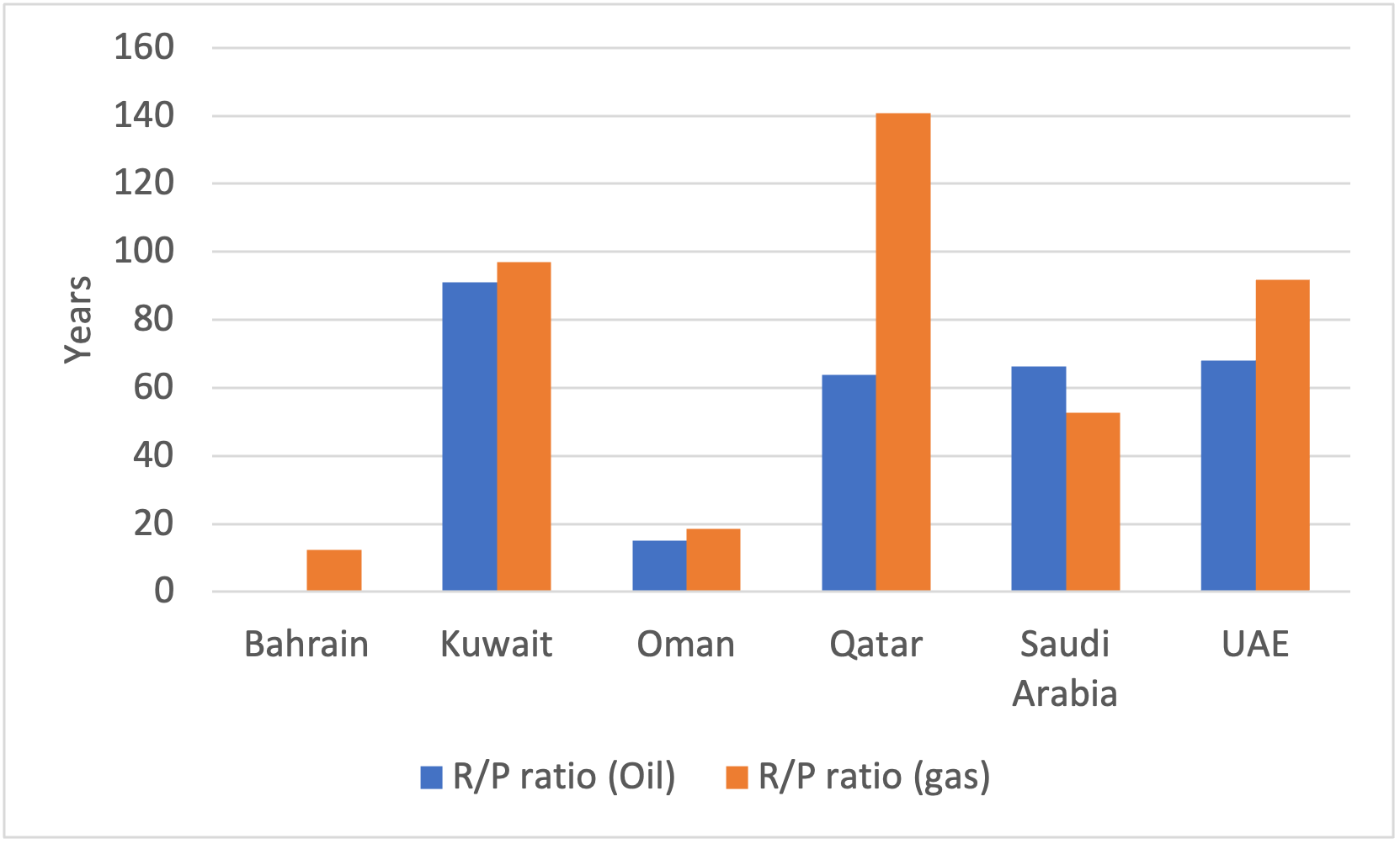

Available reserves-to-production figures suggest that Gulf Arab states will continue to have access to oil and gas reserves for the next 20-100 years (Figure 1). While the future energy outlooks suggest that hydrocarbons will continue to play a role in a net-zero future, they also suggest that the emissions generated by these fuels should be minimized using technologies such as carbon capture and storage (CCS) or by converting hydrocarbons to hydrogen or ammonia, which are free of global warming emissions.

Figure 1: Gulf reserves-to-production ratios for oil and gas

The Gulf states have made strides in rolling out low-carbon energy investments and initiatives. Yet, the gap between the current scale of these developments and where the countries want to be in a net-zero future is relatively substantial. For instance, at present, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) is home to three major CCS facilities — in Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the UAE — which together account for around 10% of global CO2 captured each year, at 3.7 million tons per annum (mtpa). By 2030, Qatar targets 7 mtpa captured and the UAE 5 mtpa, while by 2035 Saudi Arabia intends to reach 44 mtpa. Similarly, Saudi Arabia aims to produce 650 tons per day (around 0.5 mtpa) of hydrogen and 1.2 mtpa of ammonia by 2025 for export; Oman and the UAE’s Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) target 1 mtpa of green hydrogen output by 2030; and Qatar aims to produce 1.2 mtpa of blue ammonia by 2026. Assuming that these projects will run on renewable energy, the current scale of renewable energy generation, which is less than 1 gigawatt (GW) — around 4,000 megawatts — is far below what is required to meet the announced targets. It is estimated that producing 1 million tons of hydrogen would require around 6-9 GW of electrolysis capacity, operating with an efficiency of 75% for 5,000 hours per year, and around 10-16 GW of renewable energy capacity. This means that renewable energy capacity in the GCC needs to increase to almost 40-60 GW — a nearly 60-fold rise — by 2030 to meet the region’s hydrogen targets.

Are GCC governance, regulations, and policies on track to reach net zero?

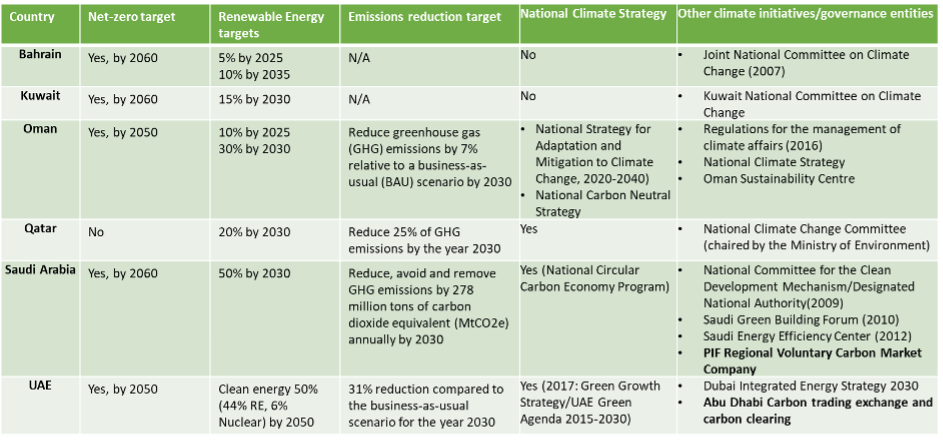

The Gulf Arab states have already taken strides and developed institutional architecture conducive to mitigating the effects of climate change. Before the announcement of net-zero commitments, each GCC state launched initiatives, regulations, and programs intended to mitigate different aspects of climate change impacts (Table 1).

Table 1: Climate-related strategies, policies, targets and initiatives in the six Gulf Arab states

-

Bahrain: In 2007, Bahrain established a Joint National Committee on Climate Change, chaired by the Supreme Council for Environment, to oversee climate issues, including mitigation and adaptation measures.

-

Kuwait: Kuwait established a National Committee on Ozone and Climate Change, chaired by the Environment Public Authority, with representatives from the General Secretariat of the Supreme Council for Planning and Development, Ministry of Oil, Kuwait Petroleum Corporation, Ministry of Electricity and Water, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and General Directorate of Civil Aviation. It also issued a National Adaptation Plan 2019-2030 in 2019 and aims to reduce its emissions of the equivalent of 7.4% of its total emissions in 2035 on a voluntary basis.

-

Oman: Overseen by the Environment Authority (previously the Ministry of Environment and Climate Affairs), Oman launched a national strategy in 2019 to mitigate and adapt to climate change and announced a national hydrogen economy strategy in 2020. In November 2022, ahead of the United Nations Climate Change Conference (27th Conference of the Parties, COP27) the Omani government announced its strategy to reach carbon neutrality by 2050.

-

Qatar: In 2021, Qatar’s Council of Ministers approved the National Climate Change Plan to inform climate-conscious decision-making across sectors. In October 2021, Qatar formed an Environment and Climate Change Ministry to address climate-related issues.

-

Saudi Arabia: In 2020, as part of its G20 Presidency, Saudi Arabia, led by the Ministry of Energy, put forward the concept of the Circular Carbon Economy (CCE) and placed it at the center of its climate mitigation plan. The CCE aims to achieve a pathway towards net-zero emissions by pursuing the “four Rs”: Reducing emissions in the first place (through energy efficiency, renewables, and nuclear); reusing carbon as an input to create feedstocks and fuels (including through mobile carbon capture technology for transportation and CO2-enhanced oil recovery); recycling carbon through the natural carbon cycle with bioenergy or natural carbon capture processes, such as forests and oceans, and the use of hydrogen-based synthetic fuels to recycle CO2; and, removing excess carbon by storing it through carbon capture utilization and storage (CCUS).

-

The UAE: The UAE was the first Gulf state to announce a national climate strategy in 2017 and was also the first to link its climate strategy with its economic development plans, for which the UAE Green Agenda 2015-2030 was established as an overarching implementation framework. The UAE Council on Climate Change and Environment, established in 2016, is the committee responsible for overseeing the implementation of the Green Agenda.

To date, however, only Oman and the UAE have put forward an economy-wide strategy paving the way to achieving their net-zero targets. These strategies set out objectives for each economic sector to achieve decarbonization goals by mid-century. These, however, lack detailed information on how — financially, technically, and institutionally — the decarbonization of each sector can be achieved. Given that net-zero objectives have been only recently announced, other Gulf states are expected to follow suit and roll out dedicated and detailed strategies to achieve their net-zero targets. These strategies need to be aligned with economic development plans and state budgets so that economic development and net-zero goals are not treated as separate agendas. Such alignment will also help to mitigate the possible unintended socio-economic consequences associated with implementing different climate policies, such as carbon pricing.

How will the GCC finance the net-zero transition?

At present, most climate-related projects are financed on an ad hoc basis. Earlier this year, for example, Saudi Arabia said it would invest up to 1 trillion riyals ($266.40 billion) to generate "cleaner energy." Back in 2015, the UAE announced a $163 billion financial commitment to achieve its 44% clean energy target by 2050. These finances are mostly sourced from the sales of hydrocarbon exports. With the exception of the UAE, none of the GCC states has put in place a dedicated climate finance framework. In 2015, the UAE government established the Green Finance and Investment Support Scheme, launched as part of the UAE Green Agenda 2015-2030. In 2021, the UAE released its Sustainable Finance Framework (2021-2031) to encourage the private sector’s involvement in the supply and demand for sustainable finance and strengthen the enabling environment for climate and green investments through strong stakeholder collaboration.

There are signs that financial institutions are increasingly participating in financing sustainable and climate-friendly projects. In 2016, more than 30 UAE-based financial institutions signed the Dubai Declaration on Sustainable Finance to promote sustainable financial practices in line with the UAE Green Agenda. In 2015, UAE national banks contributed to 10 sustainable finance initiatives, including the National Bank of Abu Dhabi targeting $10 billion over 10 years to lend and invest in environmentally sound activities; HSBC Bank Middle East funding the UAE’s first water research and learning center; sustainable integration frameworks for national banks that incorporate environmental and social risk assessment into new project finance; and green loans to incentivize customers’ climate action, such as promoting the driving of electric cars. In 2019, Oman’s core financial services provider, Bank Muscat, established the country’s first green finance scheme with scope to support rooftop solar panel installation, and in 2022, it introduced a green finance program focusing on rooftop solar for the residential market.

The region’s sovereign wealth funds have also been a key part of efforts to support green investments. In 2022, Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund (PIF) developed a Green Finance Framework, under which it aims to raise capital to support the financing and refinancing of environmental activities, covering the period 2021-25. Thus far, the PIF has released two green bonds — a financing instrument specifically earmarked to raise money for climate and environmental projects that comply with environmental, social, and governance requirements — including an initial tranche of $3 billion in 2022 and a second, larger one of $5.5 billion this year. The issuance of green bonds is aimed at supporting Saudi Arabia’s green agenda, including green investments in Neom, the Saudi Green Initiative, and the kingdom’s net-zero goals. Given the prospects for a net-zero future in which an oil-based economic model might not be as viable as it is today, Gulf countries should start developing and diversifying climate finance instruments dedicated to addressing climate mitigation and adaptation goals.

Carbon offsetting: Are nature-based solutions viable in the GCC’s net-zero pathway?

Evidence increasingly suggests that nature-based solutions (NBS) — a suite of actions or policies that aim to protect, restore, or sustainably manage natural ecosystems, biodiversity, seascapes, watersheds, and urban areas so they can tackle challenges such as food and water security, climate change, disaster risks, and human health — could contribute up to 30% of the climate mitigation needed by 2050 to meet the Paris Agreement’s objective of limiting global warming. Examples of NBS include restoring wetlands, conserving mangrove forests, protecting salt marshes, restoring forest habitats, or managing landscapes and urban areas through tree planting.

Conserving mangrove ecosystems and planting trees are two NBS that are currently pursued in the Gulf. In March 2021, Saudi Arabia announced two NBS initiatives: the Saudi Arabia Green Initiative and the Middle East Green Initiative. These aim to plant 10 billion trees in Saudi Arabia during the coming decades, with hopes of increasing the area covered by trees by 12 times from current levels and reducing carbon emissions by more than 4% of global contributions, as well as planting 40 billion trees across the Middle East. Given that the region is classified as the most water-stressed on Earth, planting trees might not be an optimal carbon offset solution for the GCC.

Gulf countries should explore other innovative carbon offset solutions that are in harmony with the region’s natural environment. Carbon capture and mineralization, a process that permanently mineralizes carbon dioxide within peridotite rock formations, could be a cost-competitive solution and compatible with the GCC’s arid natural environment, given the abundance of peridotite rock formations across the region.

The way forward

Five Gulf Arab states — Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE — have committed to achieve net-zero goals by or around mid-century. While the Gulf states have taken strides to flesh out their climate strategies and initiatives, this paper revealed that the GCC pathway to net zero, without timely and innovative intervention, could be quite difficult to achieve. Without dedicated and systematic implementation efforts to close the gap between the current state and scale of technological, financial, and institutional efforts and where the GCC countries need to be to ensure a net-zero future, the region’s ambitions might not become a reality. Timely implementation of climate policies that support net-zero goals, while challenging, will be imperative to support countries’ economic diversification efforts and mitigate the future implications of global climate policies that could imperil their hydrocarbons riches.

Aisha Al-Sarihi is a non-resident fellow at the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington and a research fellow at the National University of Singapore’s Middle East Institute.

Photo by FAYEZ NURELDINE/AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.