Iran announced last week it had developed one of the world’s most promising COVID-19 vaccines. A factory with the capacity to produce up to 3 million doses per month is expected to open in two weeks and will produce 15 million doses by June. The vaccine has completed the first phase of clinical trials and is reportedly effective against the more dangerous British variant of the coronavirus, according to Iranian officials.

The news appeared to be part of Iran’s efforts to satisfy domestic demands for a safe vaccine and to show the country is launching its vaccine rollout independently, despite the crippling economic sanctions imposed by former U.S. President Donald Trump. Officials touted Iran’s domestic vaccine research, alleging that American sanctions thwarted its efforts to purchase Western-made vaccines. While U.S. sanctions do have specific carve-outs for medicine and humanitarian aid to Iran, international banks and financial institutions are reluctant to transfer Iranian funds, fearing they may face fines.

Iran has seen the worst COVID-19 outbreak in the Middle East. The virus wreaked havoc, pushing the country to the brink of a humanitarian disaster. Hospitals and clinics failed to keep up with the surging number of patients, and drugs and medical supplies were scarce. According to official figures, the virus has killed nearly 60,000 people, but health care workers and doctors believe the real number could be four or five times higher.

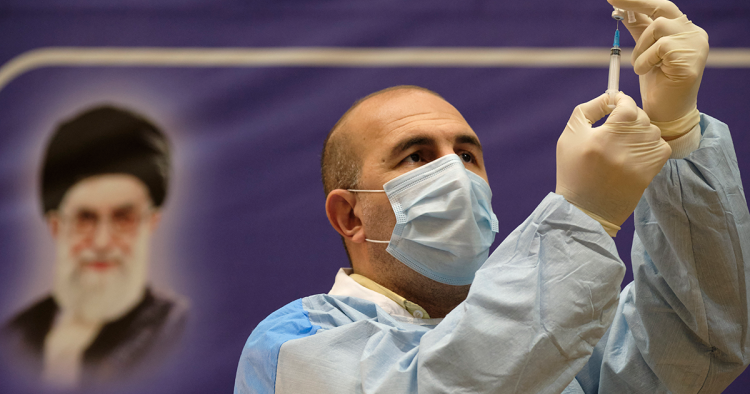

The virus and the struggle to find a vaccine revealed deep political rifts in the country and stirred up discord among officials. The country’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei banned vaccines from Western countries in January. In a tweet since removed for violating Twitter rules, Mr. Khamenei said the U.S. and U.K. possibly wanted to contaminate other nations through their vaccines. On his website, Mr. Khamenei said, “Perhaps they wish to test a vaccine on other nations to see if it works or not.” At the time, the AstraZeneca and Pfizer vaccines had already completed trials.

His decision angered many Iranians, leaving them to believe they were stuck with the virus.

Iran’s Red Crescent Society canceled an order for 150,000 doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, vowing instead to import vaccines from non-Western countries and press on with developing a homegrown alternative.

The search for an alternative

The ban did not leave many alternatives for the government but to turn to its allies who have made some progress developing or producing vaccines. The government has requested to buy vaccines from India and Russia and said it would work on a joint project to produce a vaccine with Cuba, another country hard hit by U.S. sanctions. It also launched a program to develop its own local vaccine.

Iranians are distrustful of the government in general and skepticism was high when the first batch of the Russian vaccine, known as Sputnik V, arrived in early February. Minoo Mohrez, a member of the National Headquarters for Coronavirus Control, one of the country’s top infectious disease experts, said she would not get the shot because it was not approved by the World Health Organization (WHO) or the European Medicines Agency. She said it was “misfortunate for Iranians” to get the Russian vaccine.

A hundred members of Iran’s medical council wrote a letter to President Hassan Rouhani, questioning the efficacy and safety of the vaccine. The head of the Parliament’s health committee said he, too, refused to get it.

To project confidence in the Russian vaccine, the first person to receive it on national television was the son of the health minister, Saeed Namaki — a move designed to counter public skepticism.

Ms. Mohrez insisted that the homegrown vaccine, called Barekat, is the safest option. She said phase one of the clinical trial was completed with 56 volunteers who received the first dose of the vaccine and another 30 volunteers took the second dose. Phase two is expected to begin within the next month and may be combined with the third and final phase of clinical testing. Iran has also announced a second homegrown vaccine project, known as Razi COV-Pars, that will begin clinical trials soon.

Iran is also planning to import some 17 million vaccine doses under the COVAX program, an international effort co-led by the WHO and Gavi, among others, that supplies low- and middle-income countries that might not otherwise be able to gain access to vaccines. But the government is still struggling to transfer some $220 million held in South Korean banks to pay for the vaccines.

A slow rollout

Iran expects to vaccinate 70% of its population of more than 80 million and aims to inoculate about 1.4 million before the end of the Iranian year on March 20. Vaccinations are free to encourage people to get them. So far, only 10,000 people have been inoculated.

The relatively slow vaccine rollout has fueled frustration among many who have faced lethal and harrowing encounters with the virus. The death of two former national team soccer players from COVID-19 within a week of each other in Tehran this month triggered outrage among their supporters, who gathered outside the hospital to mourn their loss. Many believe the Iranian and Russian vaccines may offer a false promise of relief.

Iranian officials hoped that President Joe Biden would break with the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” campaign that has limited their ability to cope with the virus. Irritated by lack of action on Washington’s part, President Rouhani and other officials have urged Mr. Biden in a series of interviews and social media posts to reverse his predecessor’s policies. But a flurry of provocative actions by Iran may have deterred President Biden from changing course too quickly.

Despite Mr. Khamenei’s ban on Western vaccines, Iran has purchased 4.2 million doses of the British-Swedish AstraZeneca vaccine, the first of which will arrive in the coming weeks. Officials say Iran’s doses will be produced in South Korea, offering a loophole for Mr. Khamenei’s ban.

Nazila Fathi is a journalist and commentator on Iran, a Non-resident Scholar with MEI's Iran Program, and the author of The Lonely War: One Woman’s Account of the Struggle for Modern Iran. The views expressed in this piece are her own.

Photo by Morteza Nikoubazl/NurPhoto via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.