On Aug. 25, Iran’s parliament voted on the cabinet of its new president, Ebrahim Raisi, approving 18 out of the 19 ministers put forward. Raisi’s government is full of revolutionaries likely to adopt a hardline approach to domestic and international affairs, leading to heightened geopolitical risk and potentially prolonging the country’s economic crisis.

A dubious election and the loss of hope

On June 18, 2021, the Islamic Republic held its 13th presidential election. According to official sources, turnout was 48.8% — the lowest in the history of the Islamic Republic. Raisi was elected president with 61.95% of the vote and took office on Aug. 3. The Guardian Council’s vetting of the presidential candidates, which eliminated all but seven out of the 592 registered, was widely interpreted as an effort to rig the election and may have resulted in the record number of invalid votes (14.4%, whether spoiled, blank, or otherwise inadmissible), but the low turnout is a broader sign of the declining legitimacy of the Iranian political system. The main cause of this is the poor economic performance of Raisi’s predecessor, the moderate President Hassan Rouhani, who mobilized voters in the 2013 and 2017 elections by promising to restore good relations with the West and implement structural economic reforms. Rouhani could not deliver on his lofty economic promises, however. To understand the political and economic prospects for the Islamic Republic of Iran, it is important to understand how and why Iranians lost hope in their leadership.

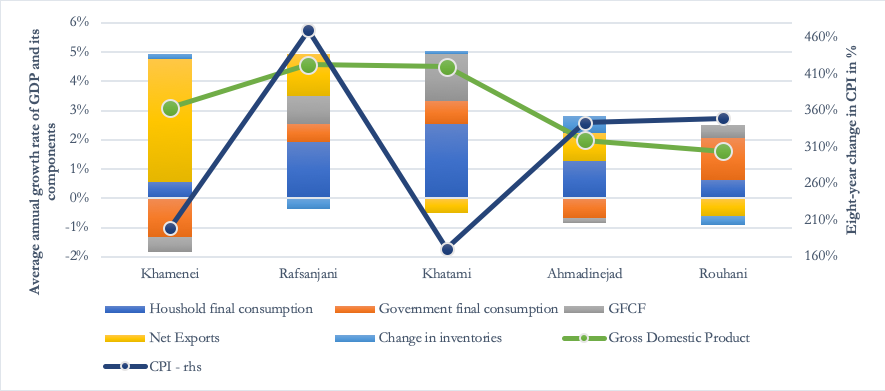

Figure 1: Iran's average annual GDP growth, contribution of individual demand components, and CPI change during the term of each of its past five presidents

Shrinking household consumption is the main driver of protests and uprisings

Looking at the average annual growth rate of GDP under each of the past five presidents, Rouhani’s government had the worst performance with an average annual growth rate of just 1.6% (see Figure 1). Household consumption under Rouhani grew at the slowest pace since the war with Iraq (during Ali Khamenei’s presidency), averaging 0.6% per year. It mostly grew during his first term in office, especially following the implementation of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2015. In his second term (August 2017-July 2021), final household consumption shrunk at an annual average rate of 0.5%. Depressed household incomes triggered nationwide uprisings in January 2018 and November 2019. In July 2021 protests also erupted in the oil-rich but economically deprived province of Khuzestan on the border with Iraq. Due to drinking water shortages resulting from a severe drought in the region, “I am thirsty” became one of protesters’ slogans. One major reason for the reduction of final household consumption under Rouhani was a deterioration in consumer confidence due to several years of recession and high inflation. As the minimum wage set by the government increased by less than inflation each year, the real wages of workers in the private sector shrank substantially. Furthermore, wage adjustment for public workers and pensioners has not compensated for the losses through inflation. Finally, from the introduction of the cash handout policy in November 2010 under President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad until April 2021, the Consumer Price Index increased by 760%, which suggests that these transfers shrunk significantly in real terms.

Discontent with the economy and frustration with four decades of oppression

Recurring nationwide protests and shrinking social capital are the results of several crises in Iran. One is a geopolitical crisis that intensified after the U.S. administration of Donald Trump withdrew from the JCPOA and imposed painful secondary economic sanctions against Iran. Another severe crisis is the COVID-19 pandemic, which hit Iran the hardest of any country in the Middle East because the government did not quickly implement sound policies to halt the pandemic’s spread early on. It also lacked the financial resources to tackle the economic downturn and trade impediments caused by the pandemic. The third crisis is a social one, caused by rising poverty rates due to the ongoing recession and increased inflation. These multiple crises have been salt in the wounds of a nation whose social, political, and cultural liberty has been suppressed by the enforcement of Islamic laws for more than four decades.

More autocratic than ever, concentrating power in Khamenei’s hands

While in Iran the rent-seeking hardliners around Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei have monopolized power in their own hands, less attention and fewer resources have been directed to the majority of the population. This suggests, that while a coup d’état from the top by powerful hardliners and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) is rather unlikely today, an uprising from below is becoming ever more likely. One can argue that the reformist President Mohammad Khatami performed best in achieving sustainable growth and low inflation as well as in increasing household consumption by boosting employment (See Figure 1). However, the political system in Iran has become intensely autocratic by pushing the reformists further and further into the corner. This has made the Islamic Republic more autocratic and ultraconservative, a system that refuses to allow the reforms that society demands.

Economic and political prospects under President Raisi

As during Ahmadinejad’s era, investment is very unlikely to rise under Raisi and this could lead to a prolonged economic crisis. This is clear from the makeup of Raisi’s cabinet, which was approved (except for the pick for the Ministry of Education) by parliament on Aug. 25. All of its members are revolutionaries who are likely to perpetuate the multiple crises facing the country without reducing the political risk around Iran’s activities and geopolitics. And business confidence is unlikely to improve without a reduction in the current political risk.

Raisi’s economic advisors, Ehsan Khandouzi at the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Finance, Hojjatollah Abdolmaleki at the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, and most importantly Mohsen Rezaee, the former IRGC commander who serves as his vice president on economic affairs and the secretary of the Expediency Discernment Council, are all Islamic economists who do not believe in liberal democracy and a market economy but rather advocate the “resistance economy.” This means that they may pursue efforts to boost self-sufficiency through inefficient semi-public companies controlled by the supreme leader, his foundations, the IRGC, and the central government, which together account for about 80% of Iran’s economy. This will push Iran’s economy to become even more isolated because it cannot compete with foreign multinationals that may want to invest in Iran in a less risky environment. Furthermore, they promise to regulate the Tehran Stock Exchange, which may allow the government to utilize public assets held by these semi-public companies as a financial instrument to help finance the government’s budget. This seems reminiscent of the failed and opaque privatizations carried out in the Ahmadinejad era, which transferred public firms to foundations and IRGC-affiliated companies. This may increase corruption but will not promote investment or foreign direct investment (FDI).

Raisi’s new vice president on economic affairs, Rezaee, has been a candidate in several presidential elections, including the June 2021 elections, and during the campaign he promised to increase cash handouts to the poorest Iranians to reduce the poverty rate, which is officially estimated at around 33%. However, financing this policy will only be feasible if and when Iran brings its oil exports back up to the levels seen prior to the imposition of U.S. secondary sanctions in 2017. Moreover, as was seen during the Ahmadinejad administration, such a policy will have an immediate impact on prices, leading to a rise and reducing citizens’ purchasing power. Instead, Iranian policymakers should advocate policies to increase employment and reduce the population’s dependency on such subsidies, which could be achieved by promoting investment (including FDI) and improving the competitiveness of Iranian industries in order to stimulate export revenues.

Due to its incompetence, bad policies, and imprudent stance against the U.S. and the West, the Iranian leadership has failed to develop sound macroeconomic policies to manage the economy properly. As a result, Iran is hit by crisis after crisis, and the frequency of these crises is becoming ever greater. The ongoing electricity shortages, the lack of money to vaccinate a population of 83 million against COVID-19, and the growing problem of climate change, exacerbated by poor infrastructure planning and mismanagement of water resources and resulting in a severe drought throughout the country, have frustrated the population.

Iranians have forgotten the power they wield since they carried out a revolution in 1979, because they have been politically, culturally, legally, and socially oppressed by their rulers ever since. However, Iranian society finally recognizes the unequal distribution of rents in favor of the loyalists of Supreme Leader Khamenei and Iranians are gradually recalling their forgotten power. This was evident in the low turnout in the presidential elections in June, but this power has yet to be fully revived to confront the theocracy and its security apparatus. Frequent social protests may further catalyze this process. The new president and his team of ultra-conservative judges and IRGC commanders were chosen to suppress the expected social unrest that is the result of the ever-deepening economic crisis.

Obviously, the indirect negotiations between the U.S. and Iran in Vienna did not bring about a renewed nuclear deal before Raisi took office at the beginning of August. However, the new president has urged the U.S. to return to the 2015 deal, which indicates his willingness to comply with the JCPOA. Because of the current monopolization of political power by Iran’s hardliners, it could be easier for the U.S. to reach a deal with Raisi. The hardliners had been sabotaging Rouhani’s policies wherever they could. Now a uniform front of hardliners in control of all the levers of power is more likely to reach a renewed nuclear deal and reap the economic dividends of sanctions relief. However, after the return to full compliance with the JCPOA, Raisi has no intention of continuing negotiations with the U.S. over other issues of concern, such as Iran’s ballistic missile program, regional tensions, and the ongoing violation of human rights.

As a result, Iran will likely become economically more dependent on China and Russia. Unlike the reformists and moderates, Raisi has no specific policy to attract FDI from the West, which could transform Iran into an advanced industrial economy. As there will remain other unresolved issues with the U.S., Western multinational companies may hesitate to invest in the Iranian market due to the geopolitical risks. Instead, as many hardliners praise Russia and China as opposed to resolving the problems with the United States, Raisi’s focus will likely be on strengthening economic relations with China. This is in line with the recent strategic partnership signed between the two countries, which can be implemented fully after secondary U.S. sanctions are removed.

Mahdi Ghodsi is an economist at the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw). His research focuses on international trade, international trade policy, non-tariff measures, industrial policy, foreign direct investment, global value chains, political economy of sanctions, and the Iranian economy. The views expressed in this piece are his own. A longer version of this article is available on the wiiw website.

Photo by Fatemeh Bahrami/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.