This article is the first in a three-part series on Iraq’s political crisis. This piece analyzes the crisis more generally while the two subsequent articles explore the perspectives of the Sadrists and the Coordination Framework specifically.

Overview of the crisis

Iraq is facing one of its worst political crises in years. Normally formed via elite political consensus, more than 11 months after Iraq’s October 2021 parliamentary elections, the government has yet to be formed, the longest such impasse since the 2003 U.S.-led invasion reset the political order. Despite calls for dialogue, neither side seems willing to make mutually acceptable concessions. On Aug. 29 bloody street battles erupted in Baghdad and then in southern Iraq, leaving more than 30 dead and many more injured. Violence has stopped, for now, but the political crisis is far from over, even if superficial solutions may be found in the interim. Iraqis anxiously await the end of the Arba’een holiday on Sept. 17 to see what will happen next.

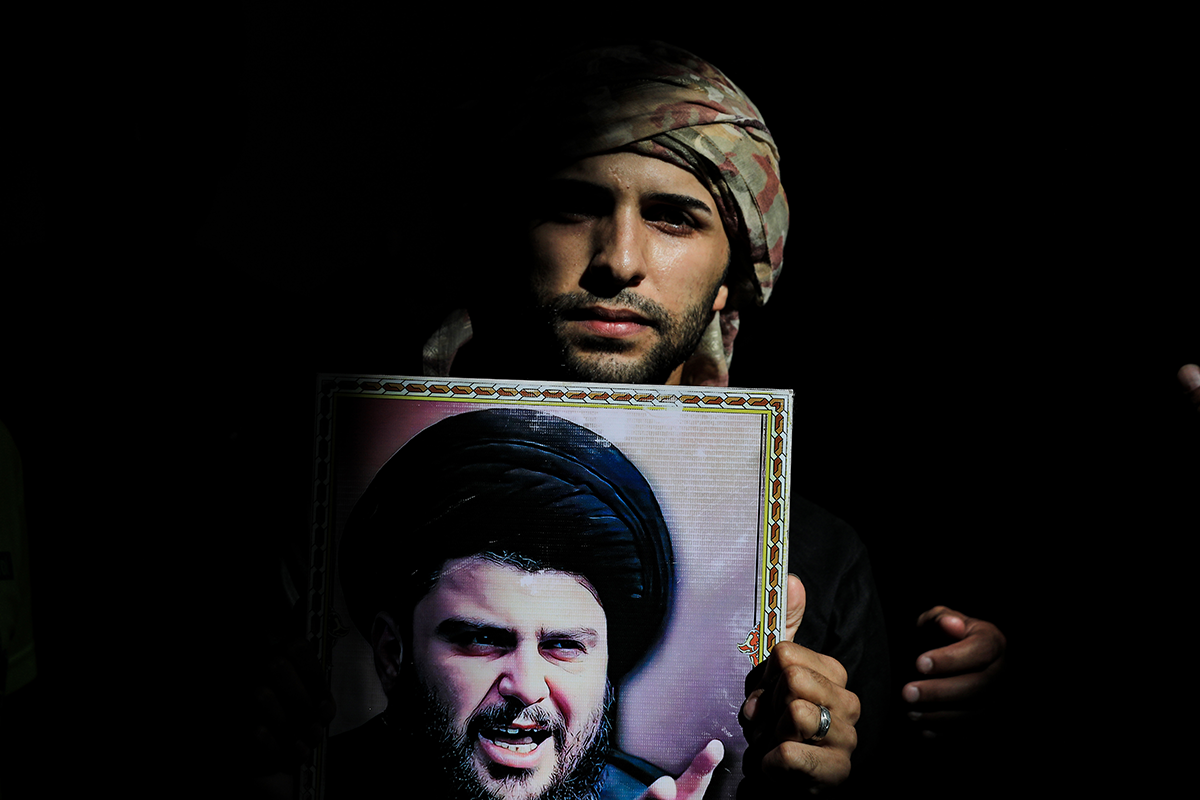

The government formation power struggle pits the Sadrist Movement, led by populist Shi’a cleric Sayyid Muqtada al-Sadr, against the Coordination Framework (CF), a loose assemblage of Shi’a parties,1 united mostly by their opposition to the Sadrist Movement.2 Central to the dispute are longstanding political rivalries and personal feuds — not divergent approaches to policy making. Competition over distribution of senior posts3 (part of the informal ethno-sectarian apportionment system known as muhassasa) is key to maintaining patronage networks. Intra-Shi’a political disputes have always existed but the overt, public rupture is unusual. Both camps claim the right to form the next government but neither has succeeded so far. For now, the Sadrists and the CF continue their tactical maneuvers, attempting to wear down and outlast the other.

Since August the author has conducted more than 30 interviews4 with individuals from the Sadrist and CF political party camps, including MPs, political officials, protesters and political party supporters, and security officials, to better understand each side’s positioning and outlook on the crisis. Many individuals spoke on condition of anonymity.

Interviews revealed that the crisis is unlikely to collapse the system of elite political consensus — neither camp would benefit from that. Moreover, the international community supports the “stability” of the current system. Both camps made lots of mistakes but two miscalculations stand out: First, when Sadr ordered his 73 MPs to resign in June, and second, later that same month, when the CF pushed to quickly replace the Sadrist MPs and attempted to move ahead with government formation. Despite criticisms, Sadr’s adherents maintain almost blind loyalty to him, viewing him as a national bulwark against foreign intervention. Opposing militias and foreign intervention are blamed by his supporters for violence and the failure of the government formation process. However, individual cases aside, and despite claims by Sadrists otherwise, parliament protests and calls for revolution failed to expand beyond his base, which nonetheless remains the biggest in Iraq. Within the CF, a power struggle exists more generally and specifically over government formation — some advocate for containing Sadr and negotiations, others for “teaching Sadr a lesson” — and this second approach played out during the Aug. 29 clashes. In general, CF actors paint themselves as the true, law-abiding partner behind whom Iraqi factions and international partners should rally. But neither the Sadrists nor the CF are true proponents of a system of law and such positioning is instead aimed at achieving political gains. Ongoing national dialogue efforts to solve the crisis are confined to dominant political actors. At some point an agreement will be reached as Sadr will not acquiesce to being sidelined and concessions from both sides will be made. What that agreement will look like and after how much more violence it will be reached remain to be seen. Broader, structural political issues plaguing the Iraqi state will remain unaddressed, to the detriment of the Iraqi people.

Timeline of the crisis

The Sadrist Movement emerged from last year’s elections as the largest single bloc. Most other traditional Shi’a political parties suffered record losses at the polls, alleging fraud, despite statements by the international community otherwise. Parties linked to the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) in particular did not do well, in part due to dissatisfaction over their reported role in the violent crackdown on the 2019 protests and constituents’ grievances over their role post-ISIS more generally. However, a key reason for their and other traditional Shi’a political parties’ subpar performance was due to poor electoral strategies under the new electoral law, often splitting their votes.5 Former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki’s State of Law Coalition was the exception — he projected himself as a strong state leader who expanded employment during his premiership, increasing his votes to become the second-largest Shi’a bloc.6 A long-time foe of Sadr, Maliki currently heads the CF. Election results hardened lines between the two opposing camps, which had begun to coalesce prior to the election.

Following his win in the October elections, Sadr attempted to forgo the customary practice of forming a consensus government among dominant political parties claiming to represent Iraq’s religious and ethnic communities (a practice not constitutionally mandated but rather an elite political consensus government, known as tawafuq, that has underpinned every government formation period since 2005), in favor of forming a “national majority government” with his allies. Sadr notably specifically sought to exclude Maliki from government formation, at times making overtures to other CF members on the condition that they exclude Maliki. Dubbed the tripartite alliance, the now failed alliance consisted of the Sadrists, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), and the Sunni Sovereignty Alliance. In the other camp stood the CF and their allies.

The tripartite alliance succeeded in reelecting Sunni lawmaker Mohammad al-Halbousi as speaker of parliament at the beginning of January 2022. But according to interviews conducted by the author, subsequent attempts to continue majoritarian government formation were allegedly stifled on several occasions7: Tripartite members KDP and Speaker Halbousi’s offices sustained physical attacks, with some alleging CF affiliates’ potential complicity, a claim which Maliki denied; the Federal Supreme Court (FSC) disqualified KDP presidential candidate Hoshyar Zebari over corruption allegations; the FSC issued a decree that the Kurdistan Regional Government’s (KRG) 2007 natural resource law is unconstitutional; and on May 15 the FSC released a decision limiting the powers of Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi’s caretaker government. Notably, the FSC’s February 2022 Ruling 16 stipulated a 2/3 quorum for parliament to elect Iraq’s president, rendering Sadr’s attempts at forming a majority government essentially numerically impossible due to the power of this “blocking third.” Critics argue that the ruling’s brief interpretation of Article 70 of Iraq’s constitution is debatable. For his part, Sadr has accused the FSC of political bias.

But Sadr is not alone in questioning the judiciary’s intentions. Media commentators and activists have similarly accused the judiciary and Supreme Judicial Council (SJC) President Faiq Zaidan of alleged political interference throughout this government formation period.

By June 13, majority government formation efforts ground to a halt when Sadr ordered his 73 MPs to resign. Accordingly, Sadrist MPs were replaced by the second runner-up in the elections, which in many instances saw CF MPs taking their place. The CF moved quickly to announce Mohammed al-Sudani, a former minister and former governor of Maysan Province, as its candidate for prime minister. Sudani is perceived by Sadr loyalists as doing Maliki’s bidding. In July, leaked audio recordings, apparently of Maliki, warning of civil war and denouncing political rivals, especially Sadr, rocked Iraq. Maliki claimed the tapes are fabricated but many experts say they are real. The tapes blocked any hopes — even if remote — that Maliki had of securing a third term as prime minister. Sadr demanded, in turn, that Maliki quit politics.

Capitalizing on the explosive Maliki leaks, Sudani’s proposed nomination for prime minister, and the religious holiday of Ashoura (which commemorates the martyrdom of the Prophet Muhammad’s grandson, Imam Hussein), Sadr announced the “Ashoura Revolution.” On July 30, Sadr’s supporters stormed and occupied parliament for the second time in a week to protest their rivals’ attempt to form a government. Praised by his followers as the “leader of reform,” Sadr initially called for reforms but then later advocated a radical change of the political regime, a new constitution, and fresh elections. The sit-in, which was later moved outside the parliament building, lasted nearly one month.

Iraqi security forces initially used tear gas and sound bombs to repel demonstrators on July 30, leaving more than 100 protesters and 25 members of the security forces injured, but later backed off when protesters occupied parliament and declared an open-ended sit-in. The relative ease with which protesters occupied parliament suggests coordination or at least tacit acquiescence by government officials. Political opponents point fingers at Prime Minister Kadhimi.

This was not the first time that the Sadrists had stormed the Green Zone. In 2016, videos circulated of Iraqi security officials receiving Sadr as he entered the Green Zone to join his supporters’ sit-in, calling for an end to the political quota system. Facing backlash, army Lt.-Gen. Mohamed Reda subsequently resigned from his post. He later ran with the Sadrist Movement in the 2018 parliamentary elections and won.

Sadr’s supporters’ relative peaceful storming of parliament in 2022 stands in direct contrast with the bloody crackdown inflicted upon Tishreen protesters starting in 2019. More than 600 protesters were killed and more than 20,000 injured in the first six months alone. Sadrists say that the Ashoura Revolution includes Tishreen activists and supporters from across Iraq, and while some activists have been involved on a more individual basis and expressed some similar demands for reforms, emerging parties and civil society activists told the author that they have generally tried to distance themselves from the protests.

The role of the courts and allegations of bias have been central to the dispute. On Aug. 10 Sadr tweeted that the SJC should dissolve parliament and “depoliticize the judiciary.” President Faiq Zaidan responded that such a move is not supported by the constitution. On Aug. 23 the Sadrists expanded their sit-in to outside the judiciary. In response, the SJC said it would shut down until further notice but later reversed the decision when the Sadrists withdrew.

Political conflict turns deadly

Political officials from both camps reiterated to me throughout the month of August that neither the Sadrists nor the CF planned to escalate the crisis with violence. But in the days leading up to Aug. 29, violence seemed imminent. One official, speaking on condition of anonymity, confirmed as much, saying he left the Green Zone just days before violence erupted.

On Aug. 29, Iran-based Ayatollah Kadhim al-Haeri announced his retirement from his role as marja’a8 for health reasons and directed his followers toward Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, instead. Haeri had taken up this position in succession to Sadr’s father years before. While he did not mention him specifically by name in the announcement, Haeri was clearly criticizing Sadr’s actions and credentials. Relations between Haeri and Sadr had been strained for years; but nonetheless, this was a major insult to Sadr. More importantly, for a marja’a to retire and direct his followers elsewhere is unprecedented. As such, Sadr suggested that Haeri’s resignation was not of his own accord, hinting at an Iranian power play. Sadr then announced his retirement from political life.

Soon afterwards his followers stormed Baghdad’s Green Zone and occupied the government palace. Members of Saraya al-Salam, the Sadrist movement’s armed wing, were then reportedly seen driving through Baghdad brandishing weapons. The exact details of what unfolded next are still coming to light. Reports suggest that members of armed groups aligned with the CF fired on Sadrist protesters, igniting deadly clashes between the two, and dragging Iraqi security forces into the fray. Revenge killings in southern Iraq followed. Tit-for-tat assassinations have occurred off and on between the Sadrists and Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq9 in the past, especially in Maysan Province, but not on this level. In a statement released on Aug. 30, Sadr condemned the violence, apologized to the Iraqi people, and directed his followers to leave the Green Zone, which they did within the hour.

The violence left 30 people dead and many more injured. But as quickly as it escalated, it deescalated, underscoring the dark reality of political violence. All-out civil war is not in the interest of the ruling elite, but many fear more killings.

Recriminations continue on social media. On Sept. 1, “the minister of the leader”10 called for removing Falah al-Fayadh as PMF head and forcing the PMF out of the Green Zone. In turn, CF-aligned social media accounts called for Saraya al-Salam to be removed from the PMF. Days later, leaked voice recordings, purportedly of senior Sadrist officials criticizing Sadr, were shared on social media.

On Sept. 5, Prime Minister Kadhimi led a national dialogue session, but the Sadrists’ representative did not attend. On Sept. 7, the FSC ruled that it does not have constitutional authority to dissolve the legislature, but noted that parliament violated its constitutional deadlines. On Sept. 11, KDP leader Masoud Barzani, Parliament Speaker Halbousi, and Sovereignty Alliance chief Khamis al-Khanjar met in Erbil to affirm their support for early elections, which should follow “the formation of a government that has full authority.” The meeting was held days after Sadr called on his counterparts to resign from parliament and marked the official end of the tripartite alliance.

An unspoken agreement among leaders will keep calm until Arba’een concludes on Sept. 17.11

A path toward consensus?

While Sadr has repeatedly called for reforms over the years, the Sadrists are very much part of the system, leading several ministries and holding powerful positions within central and governorate-level institutions. Sadr’s CF political rivals do as well. Both camps alternate between standing behind or undermining the government and its institutions as it fits their political agenda. As he has done in the past, Sadr tried to use protests and street mobilization as leverage to negotiate with CF rivals, and not to push radical reform.

The current stalemate is therefore a crisis of elite, consensus-based politics. At present, no one actor has enough power to act as sole kingmaker in Iraq and the current system “works” when a form of elite consensus is reached for government formation. This is not to say that the current system is the “best” by any means; this is merely a description of how it normally operates.

The situation is a complex, multi-layered political impasse. Both camps made lots of mistakes along the way. But we can pinpoint two miscalculations on part of Sadr and his CF rivals that exacerbated this summer’s standoff and tipped it further away from consensus and deeper into quagmire. First, when Sadr ordered his 73 MPs to resign and second, when the CF pushed to quickly replace the Sadrist MPs and announced Sudani’s proposed nomination for prime minister. As one official from the CF told the author, “Iraq does not stop for Sadr.” But the CF does not call all the shots and they should have anticipated that the leader of the largest Shi’a political bloc would not acquiesce to being completely sidelined. At some point, hardliners within the CF will have to be convinced to make some concessions, as will Sadr. Unless there is an overhaul of the system, that’s not how elite political consensus works.

The collapse of the tawafuq system remains highly unlikely — as is all-out civil war. Too many elites across the political spectrum have too much to lose, including from the Kurdish and Sunni blocs. The international community and the U.N. also appear to prefer the “stability” of the current system.

The future is hard to predict, but it’s unlikely that Sadr will be willing to completely stay outside the system and will require concessions, even if these are not publicly acknowledged. Developments after Arba’een will answer two important questions: What extent of political violence are elites willing to weather until an agreement is reached? And what concessions will prove mutually agreeable?

Beyond the current stalemate, the crisis raises many important questions about Iraq’s future. What does this mean for the future of Iraqi elections and the role of the largest bloc in government formation? With elite consensus driving politics and government formation, what role can emerging parties play? If early elections were a solution, wouldn’t the most recent early election have solved the issue? And under which electoral law? The Sadrists benefitted from the previous electoral law and are not likely to accept revisions without a fight. Moreover, elections are not something that can be planned overnight; most politicians and political experts interviewed by the author said that at least a year and a half would be needed to organize and run “early” elections. A lot can happen in that time.

Agreements will not resolve the fundamental political issues plaguing Iraq; instead, the focus will be on satisfying the demands of the political elites. What will the Iraqi people’s future be? As one Iraqi academic lamented to the author, “We are damaging everything that should be a foundation for our political system: the courts, the parliament, and the constitution.”

Haley Bobseine is a Middle East-based researcher and analyst and a PhD Candidate at King's College London. The views expressed in this article are her own.

Photo by AHMAD AL-RUBAYE/AFP via Getty Images

Endnotes

- According to the author’s interview with an official from Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq, the Coordination Framework is a loose umbrella coordination framework and not an official alliance.

- Previously Sadr had been part of the informal group with other dominant Shi’a parties until he withdrew in July 2021 ahead of the elections. Following the October elections, the Coordination Framework was formed.

- The prime minister is historically Shi’a, one of the most powerful positions in government.

- Most interviews were conducted in person in Baghdad in August, with some interviews conducted remotely in September.

- For a detailed breakdown of election results by governorate, see Kirk Sowell’s Inside Iraq Politics subscriber-based issues published in the months following the October 2021 election. https://twitter.com/uticarisk

- Maliki, however, did support efforts challenging the election results. See this report for more information: https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf-and-arabian-peninsula/iraq/iraqs-surprise-election-results.

- Some interviewees knowledgeable about the government formation process and speaking on condition of anonymity said that some within the CF used physical threats and the judiciary in attempts to block government formation not in their favor.

- A marja’a is a Shi’a religious scholar with the necessary credentials to serve as a religious guide to his followers.

- Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq is a Shi’a political party and armed group. It is part of the PMF and the CF and is close to Iran.

- Salah Mohammad al-Iraqi (also known as the “minister of the leader”) is Sadr’s anonymous online surrogate.

- Millions of Shi’a from across the world are currently in Iraq undertaking a pilgrimage to mark the 40th day after the anniversary of the martyrdom of Imam Hussein, known as Arba’een. Any potential upcoming parliament session won’t be held until after the holidays.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.