Post-occupation Iraq's oil production ― buoyed by the existence of vast unexploited reserves ― is resurgent. After two decades of sanctions and war, Iraqi oil production shot up to 3 million barrels per day (mbd) in July 2012, reaching 3.4 mbd in December, and overtaking Iran as the second largest producer in OPEC. These remarkable gains are attributable to increased investment in Iraq’s petroleum industry and export infrastructure. With export volumes hovering at around 72% of its total production, Iraq has become the world’s third-largest oil exporter. Given that 95% of the country’s revenue is generated by oil sales and 90% of Baghdad’s own energy needs are met by petroleum, there is a strong sentiment for raising production levels and improving export capacity.

According to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), Iraq may be one of the few countries whose known hydrocarbon resources have not been fully harnessed. Iraq has huge stockpiles of so-called “cheap oil” (i.e., untapped reserves extractable through relatively inexpensive traditional drilling methods). This is in contrast with shale oil reserves in North America and Australia as well as deep water finds in the Gulf of Mexico, where costly technologies, such as, hydraulic fracturing or “fracking” and deep-sea exploration are employed to access oil.

Iraq’s potential to greatly increase conventional oil production at low costs is now widely recognized. Chief economist of International Energy Agency (IEA), Fatih Birol, has described Iraq as a dream for the energy industry, with “high oil reserves, easy geology and low production costs.”[1] Therefore, Baghdad is bound to play a critical role in determining the cost of oil and future oil market stability, with demand for energy rising rapidly in developing economies such as China and India. With several reports warning of a scenario in which, possibly as early as 2015, major exporters such as Russia and Saudi Arabia are unable to substantially ratchet up production, Iraq might be on the path of becoming a “strategic source” of oil supply to world economies.

Iraq’s Proven Oil Reserves

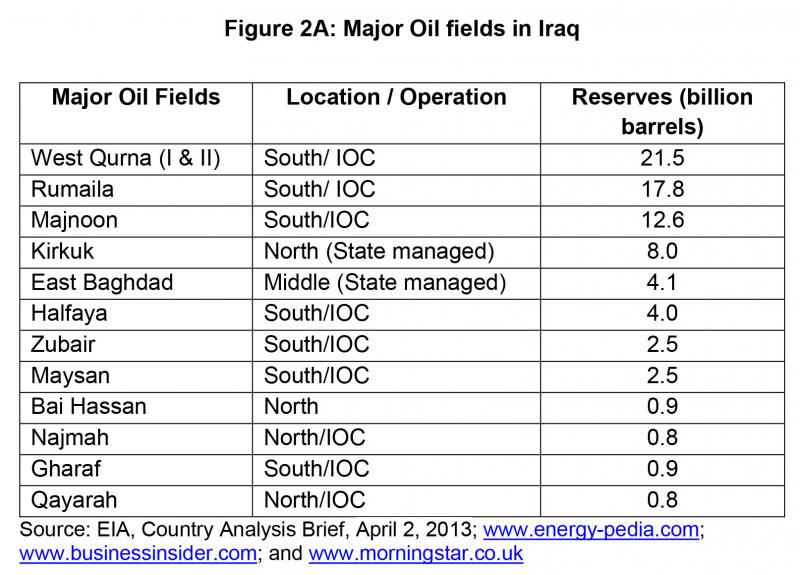

According to the EIA, as of April 2013, Iraq’s proven crude petroleum reserves stood at 141 billion barrels, the fifth largest after Saudi Arabia, Venezuela, Canada, and Iran. (See Figure 1 for proven oil reserve over a ten-year period of all five oil producers). These are found in 79 hydrocarbon fields (70 oil and 9 gas fields), of which only 23 are operational. Although, Iraq’s large resources are concentrated in the south and north of the country (only one in the middle), a majority of the known energy reserves in the country form a belt that runs along the eastern edge of the country.

Figure 1: Crude Oil Proven Reserves - Top Five Countries

Source: US Energy Information Administration (EIA), International Energy Statistics (2013), http://www.eia.gov/cfapps/ipdbproject/iedindex3.cfm?tid=5&pid=57&aid=6&….

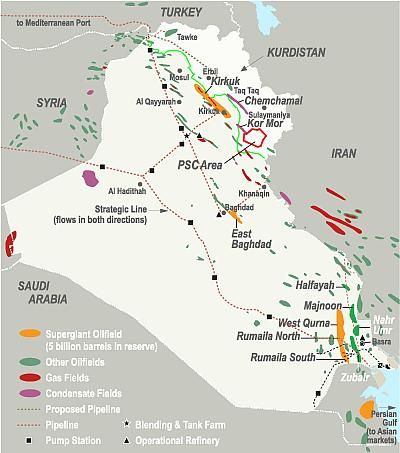

Iraq has five super-giant fields (each containing at least 5 billion barrels in reserve) in the south that account for 60% of the country’s proven oil reserves. These oilfields are West Qurna (Phase I and II), North and South Rumaila and Majnoon in the south. An estimated 17% of oil reserves are in the north of Iraq, near Kirkuk, Mosul, and Khanaqin. About three-fourths of Iraq’s crude oil production comes from the southern fields, with the remainder primarily from the northern fields near Kirkuk and East Baghdad middle field. The IEA estimates that the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) area contains 4 billion barrels of proven reserves. However, this region is now being actively explored, and the KRG has stated that this area could contain 45 billion barrels of unproven oil resources.[2] (See Figure 2A and 2B for major oil fields in Iraq.

Figure 2B: Locations of Iraq’s Major Oil Fields

Source: "Iraq: Shell and Petronas Consortium Awarded Majnoon Oil Field," Energy-pedia News (December 11, 2009), http://www.energy-pedia.com/news/iraq/shell-and-petronas-consortium-awarded-majnoon-oil-field.

Source: "Iraq: Shell and Petronas Consortium Awarded Majnoon Oil Field," Energy-pedia News (December 11, 2009), http://www.energy-pedia.com/news/iraq/shell-and-petronas-consortium-awarded-majnoon-oil-field.

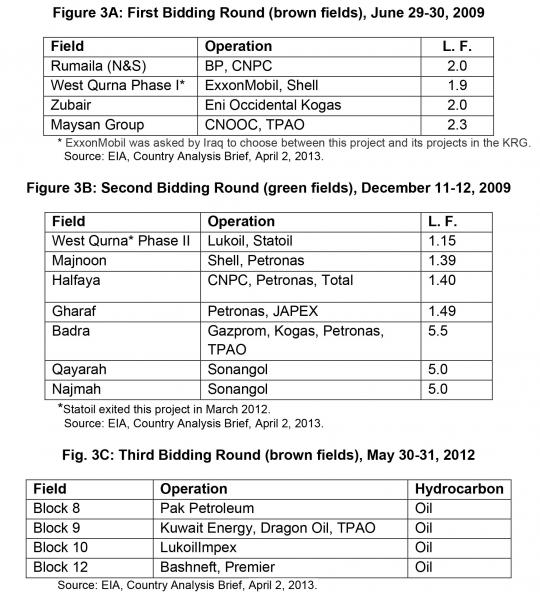

In June and December 2009, the Iraqi government, through two bidding rounds, concluded 11 service contracts with 18 International Oil Companies (IOC). Iraq’s model contract with oil companies envisages a 20-year service agreement, wherein, the government has 25 per cent stake, while the IOCs have the remaining 75% stake. The government pays the operating company a fixed fee (approx. $2–6) per barrel of oil produced, thereby offering the IOC the prospect of benefitting from any upside and incentivizing it to maximize production. The IOCs have not been given exclusive rights to either exploration or production, with the host government retaining ownership of the hydrocarbon resources under such arrangements.

In the first phase, contracts were given for capacity addition of existing “brown fields” (i.e., giant oilfields as well as smaller fields that were already producing, namely West Qurna Phase I, Rumaila and Zubair). The contracts in the second phase were signed to develop “green fields” (i.e., discovered and appraised fields not fully developed or producing commercially, specifically West Qurna Phase II, Majnoon, Halfaya, Gharaf, Badra, Qayarah, and Najma). All together, the contracts for the two phases cover oil fields with proven reserves of over 60 billion barrels. A third bidding round was conducted for natural gas fields.

The fourth round of licensing in May 2012 was the first to offer exploration contracts compared to the technical contracts offered in the first three rounds as it involved areas with undetermined levels of hydrocarbons. However, it failed to generate expected bidding interest from IOCs, concerned about potential for return from exploration of new fields within the context of possible OPEC quota restriction of about 4.5 mbd on Iraq. The Iraqi government has indicated it would sign up to OPEC quota as early as 2014, which would make the Oil Ministry’s plan to increase production to 7mbd by 2015 superfluous.[3]A fifth round has been scheduled for December 2013 for the development of the 4 billion barrel Nasiriya oil field in Dhiqar province in the southwest of the country (See Figure 3A, 3B, and 3C for the results of biddings rounds).

Infrastructural Constraints

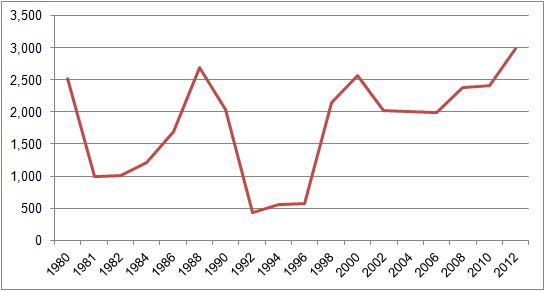

Iraq has seen robust production growth since 2007, primarily due to improved security environment over previous years and investments by IOCs, which have brought Iraqi oil production to their highest levels in 30 years (See Figure 4).

Figure 4: Iraq's Oil Production, 1980-2012 (in thousands of bpd)

Source: EIA (2013).

Nonetheless, it has been their perennial concern that much of the existing infrastructure in Iraq is woefully inadequate to handle the planned increases in energy production. The existing ones need massive upgrading, and a considerable number of new ones will have to be built in order to handle significant increases in crude oil production over current levels. The twin outlets, namely export and refining, that move crude from the site of production to the market are hamstrung by old pipelines, paucity of storage terminals, low-grade ports, and persistent security threats. Progress has also slowed because of political disputes between political factions within Iraq, especially those between the federal government in Baghdad and the autonomous Kurdistan Regional Government.

Expanding production on the scale planned will also require substantial increases in natural gas and/or water injection to maintain oil reservoir pressure. Iraq has associated gas that could be used, but it is currently being flared. While locally available water is currently being used in the south of Iraq, large amounts of seawater will have to be pumped in via pipelines that have yet to be built for the Common Seawater Supply Facility. According to estimates by Iraq’s Deputy Prime Minister for Energy, energy infrastructure in Iraq requires capital expenditures of $30 billion annually to meet production targets.

Pipeline overhaul and construction is the most important aspect of infrastructure development. A 6,000 km long on-shore pipelines and 300 km of offshore pipelines are required to meet current production and future targets. Oil storage expansion is another area demanding immediate attention. An urgent addition of 20 million barrels to existing facilities is needed to store oil being produced in the running Iraqi fields. New tank farms with 30 million barrels are required to match increase in production. A final storage capacity with 60 million barrels would take care of storage facilities when the remaining oil fields come into operation. The seawater supply facility of 12–15 mbd is required for more efficient use of oil wells in the north and middle of the country. Loading terminal capacity expansion involves speedy enlargement of the existing loading terminals with an additional capacity of 1.6 mbd and construction of 4 new single point moorings (SPMs) with a total capacity of 3.2 mbd. A capacity of 4.8 mbd is a reasonable target in the medium term.

Current Iraqi refining capacity, estimated at over 900,000 bbd, does not meet the current demand mix. Despite improvements in recent years, the sector has not been able to meet domestic demand for most refined products such as gasoline, and the refineries produce too much heavy fuel oil relative to domestic needs. As a result, Iraq continues to import about one fourth of the local petroleum products demand. The country has plans for four new refineries; one with a capacity of 300 kb/d and two with 150 kb/d and one with 140 kb/d, as well as plans for expanding the existing Daura and Basrah refineries. These new refineries are open for private investment.

Challenges to Iraq’s Oil Sector

Insecurity and instability continue to impede the development of Iraq’s oil sector. Major oil companies operating in Iraq are wary of making more investment and many others are staying away from investing in Iraq’s oil resources. American companies such as Chevron, ConocoPhillips, and Suncor are not in the reckoning anywhere in the country. Nearly daily bombings in one part of the country or another creates negative image for investment climate in the energy sector and other sectors as well.

Oil infrstructure, especially pipelines, have been the target of insurgency since 2003. The attack on pipelines on March 25, 2013 at Tulool-Al baj in northern Iraq halted oil exports to Turkey, and the attack on a pipeline in Tikrit in northern Baghdad on April 10, 2013 resulted in a major fire in the pipeline. According to Iraq Pipeline Watch there have been hundreds of such attacks in the past decade.[4] These frequent terrorist attacks have been major impediments to an obstacle to development of the Iraqi oil sector. One of the many reasons for lack of interest by major oil companies in the fourth licensing round was their shared concern about the security of investment in the country.

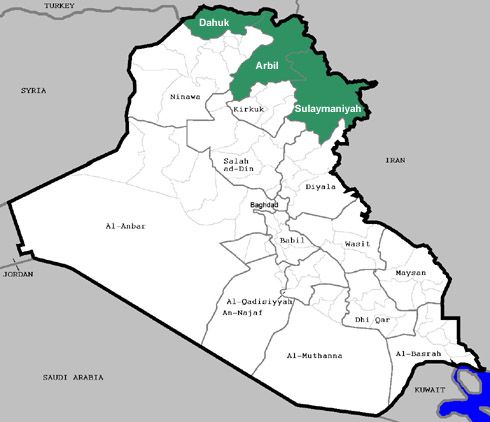

The continuing dispute between the central government and the semi-autonomous KRG in northern Iraq (See Figure 5) is a major impediment to development of energy infrastructure and realisation of the country’s export potential. A comprehensive hydrocarbon law is hanging fire since 2008 in the Iraqi parliament, causing project delays and inhibiting long-term production targets. The central government in Baghdad argues that the KRG has no legal authority to independently export oil or sign oil development contracts with the IOCs. However, in October 2012, the KRG started exporting oil via truck to Turkey’s Ceyhan port and has signed independent contracts with Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Gazprom for development of oil fields in the north. The Kurds, however, maintain that they have acquired the right to do so in the 2005 Constitution.

Figure 5: Iraq’s Kurdish Region (KRG)

Source: http://musingsoniraq.blogspot.in/2013/02/have-iraqs-oil-exports-hit-pla…

Baghdad has banned IOCs doing business with the KRG from bidding on any future contracts. For instance, Iraqi Oil Minister in January 2013 ordered ExxonMobil to decide between Kurdistan and southern Iraq. Many in Baghdad argue that the KRG’s oil policy has the potential to splinter the country by tempting oil-rich region to enter into independent deals. This dispute, along with broader security concerns, has undermined Iraq’s drive to boost oil production and earn more revenue.

Widespread corruption in the Iraqi Oil ministry is another serious internal challenge that Iraq faces, as it strives to modernize its oil sector. With the country’s oil production on the rise, several acts of ommision and commission are resulting in revenue flowing into private coffers instead of the government’s treasury. There were reports of non-installation of metering and monitoring systems, on the recently inaugurated floating platforms, necessary to accurately measure the quantity of oil being exported via tankers. If this is true, then the primitive al-Dhir’a method used to calculate the amount of oil exported in a tanker manually carries the possibility of loss of oil revenue to the government in millions of dollars.

Experts estimate that 150,000 to 200,000 — and perhaps as many as 500,000 — barrels of oil per day are being stolen. Controlled prices for refined products result in shortages within Iraq, which drive consumers to the thriving black market. Several parliamentarians complain they know very little about the Ministry of Oil’s work or the contracts it signs because of the partial availability of reports about the ministry’s performance to the parliament and its energy commission.[5]

OPEC production quotas present another challenge to rapid growth of Iraq’s oil industry. The country has been exempt from the quota system of the international oil body since 1998 due to sanctions and war, which reduced Iraq oil production to a miniscule amount. Large producers such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Venezuela have absorbed Iraq’s production quota. Iraq’s reentry into the OPEC’s quota system in 2014 might conflict with its budgetary requirements. Iraq might not be allowed to produce more than 4.5 mbd to prevent the prices from tumbling downhill. On the other hand Iraq would want to produce more given the rejuvenation of its oil sector and earn more revenue from its struggling economy. The conflicting facts would need to be reconciled as Iraq’s space is sculpted within the OPEC production quota system. Iraq could receive special exceptions to raise export capacity, given the country’s need for oil revenue.

Iraq’s internal security problem is compounded by the fact that it also faces instability on its external front. This has had a telling impact on the security of pipeline routes to the Mediterranean. For instance, Kurdish separatists have frequently targeted the Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline. Iraq's plans to expand the country's oil (and gas) export options by constructing new pipelines through Syria are unlikely to materialize anytime soon, given the ongoing conflict and possibly prolonged instability there. Further, if the oil rivalry between Iraq and Iran is rekindled, as the former takes over the latter in production and oil sales, Baghdad’s energy transaction through the Straits of Hormuz may be in jeopardy. In their zeal to ramp up production, Iraqi officials must always keep in mind this lurking danger.

Iraqi Oil: The Asia Connection

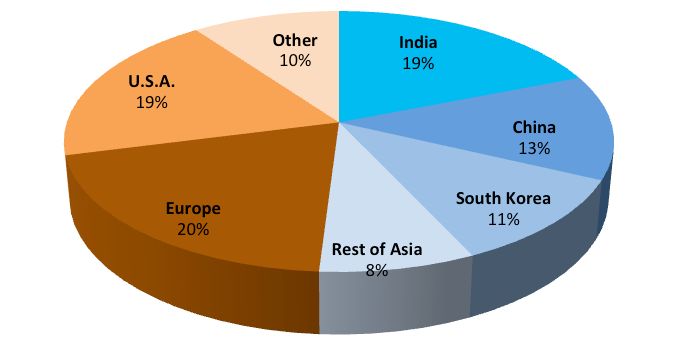

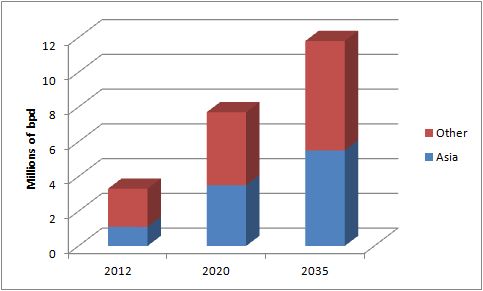

According to EIA, the Lloyd’s List Intelligence shows that a majority of Iraqi oil exports went to Asia, especially India, China and South Korea, in 2012 (See Figure 6). The IEA forecasts that by 2020, Iraq will export 80% to Asia, and by 2035 (See Figure 7), a quarter of Iraqi oil, about 2 mbd, will be headed for China. Already oil from Iraq has been steadily replacing Iranian oil in the Indian market. In 2012 Iraq was India's second largest supplier of crude oil (13% of total supply) after Saudi Arabia (19%).[6] The movement of Iraqi oil to the Asian region reflects the emerging structural change in the global market. This trend is attributable to several factors, including the downturn in Western economies since 2009, increased production from domestic US oil supplies, and increased efficiency in energy consumption in parts of Europe.

Figure 6: Iraq's Oil Exports to Asia and Other Destinations (2012)

Source: Lloyd List Intelligence quoted in EIA, Iraq Country Analysis Brief (April 2, 2013).

Figure 7: Iraq's Oil Export Destinations -- The Asia Connection

Source: Iraq’s Energy Outlook, International Energy Agency’s Special Report (October 2012).

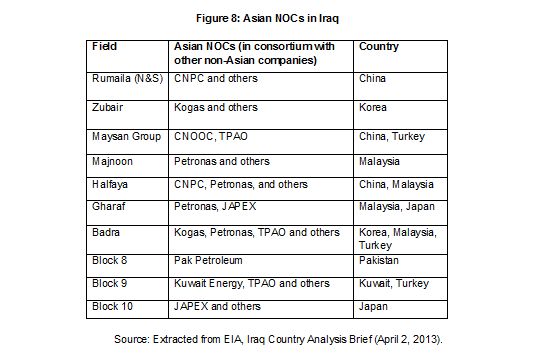

While the Western oil companies (oil majors) are becoming increasingly wary of the political instability, poor contractual terms and infrastructure bottlenecks, Asian oil companies having sovereign backing are faring well in the country. They have bagged quite a few production contracts in Iraqi oilfields (See Figure 8).

Tending to be less risk averse than many of their Western counterparts, Asian national oil companies (NOCs) are increasingly making their presence felt. China, Malaysia, South Korea, and Japan are involved in operating several small and large oil fields. Chinese NOCs are doing better than the rest of the Asian countries with presence in both large and small fields. CNPC is a partner in the BP-led consortium developing Rumaila, the largest known oilfield in Iraq, and also operates the Ahdab field. While CNPC also operates Halfaya in consortium with Malaysian Petronas and Total, CNOOC operates the Maysan group of fields with Turkey’s TPAO. South Korea’s Kogas is developing the Zubair field in consortium with Eni, Occidental and Iraq’s state oil companies. Japan is developing the Gharaf green field in partnership with Petronas. A new trade partnership appears in the offing between Iraq and the Asian countries.

Conclusion

Iraq today produces about a million barrels of oil more than it did in the immediate aftermath of the US-led invasion in 2003. In October of last year, the International Energy Agency (IEA) predicted that Iraq’s production could double by 2020. Yet, in spite of the impressive recovery and vast potential of the Iraqi oil sector, its further development is constrained by insecurity, bureaucratic bottlenecks, infrastructure deficiencies, unresolved legal issues, and political disputes. Nevertheless, these roadblocks and uncertainties have not frightened away Asian NOCs. On the contrary, as much as one third of all future Iraqi oil production could come from Chinese-owned fields alone.[7] The IEA’s Chief Economist, Fatih Birol recently declared that, “A new trade axis is being formed between Baghdad and Beijing.”[8] The Iraq-Asia oil connection — an important feature of the changing global energy landscape — is already firmly established and developing rapidly.

[1] Guy Chazan and Javier Blas, “IEA Predicts Boom in Iraq Oil Production,” Financial Times (October 9, 2012), http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/9dff8352-112e-11e2-8d5f-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2SjQ4N1zP.

[2]Energy Information Administration (EIA), Country Analysis Brief (April 2, 2013), http://www.eia.gov/countries/cab.cfm?fips=IZ.

[3] Omar al-Shaher, “Iraq Aims to Increase Oil Output,” Iraq Business News (March 29, 2013), http://www.iraq-businessnews.com/tag/oil-production/.

[4] “Attacks on Iraqi Pipelines, Oil Installations, and Oil Personnel,” Iraq Pipeline Watch, http://www.iags.org/iraqpipelinewatch.htm (March 27, 2008).

[5] Omar al-Shaher, “US, Iraq Seek to Boost Oil Transparency,” Iraq Pulse, Al-Monitor (March 22, 2013), http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2013/03/baghdad-washington-oil-agreement.html.

[6] Energy Information Administration (EIA), India Country Analysis Brief (March 18, 2013), http://www.eia.gov/countries/cab.cfm?fips=IN.

[7] Sean Cockerham, “Iraqi Oil: Once Seen as US Boon, Now It’s China’s,” McClatchy (April 2, 2013), http://www.mcclatchydc.com/2013/03/27/187100/iraqi-oil-once-seen-as-us-boon.html#.UYq1e1Lm7Pg.

[8] Quoted in “Big Oil’s Hassle With Iraq is China’s Gain,” UPI (March 29, 2013), http://www.upi.com/Business_News/Energy-Resources/2013/03/29/Big-Oils-hassle-with-Iraq-is-Chinas-gain/UPI-53711364583572/.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.