Part survey show, part historical document, the latest exhibition at the Palestinian Museum just outside of Ramallah, Intimate Terrains: Representations of a Disappearing Landscape, covers work from the 1930s until today. The show, on through the end of December 2019, explores how representations of landscape evolved over time via a selection of iconic, rarely seen works, and special commissions by artists from Palestine and its diaspora, encompassing painting, photography, installation, video and film, natural media, sculpture, and even an “intervention” in the museum’s gardens. The 36 participating artists range from Sliman Mansour and Nabil Anani to contemporary video artist Larissa Sansour.

The Palestinian Museum opened in 2016 as the culmination of nearly two decades of work by the Taawon-Welfare Association, an independent Palestinian non-profit organization. Located next to Birzeit University, the roughly 40,000-square-foot museum is designed to serve as a hub for Palestinian culture and a connector to the larger diaspora.

While survey shows can be problematic and representational issues often become an albatross for Palestinian artists, Intimate Terrains transcends its encyclopedic approach by offering fresh perspectives on the importance of Palestinian art — both aesthetically, and as a form of resistance.

Indeed, exploring the connection of Palestinian artists to the land is less an art world ambition than a deeply moving gestalt. As guest curator Dr. Tina Sherwell writes:

“The depiction of landscape over the decades provides us with a prism onto the experience of loss and longing, a prominent subject matter for artists, as its topography holds a central place in Palestinian identity formation. Landscape is at once both a vast site of projection and a deeply layered terrain of remains, memories, and histories.”

In fact, the exhibition fulfils the mandate of the relatively new museum, and also expresses the architectural spirit of the building itself. Heneghan Peng Architects chose to express the often-fraught issue of Palestinian identity by deriving its form directly from the landscape, following the existing contours of the land to create a building that emerges organically from the site.

While many institutional buildings in Palestine read like stone fortresses, the museum opens itself to its land and its people; in a place of barriers, there is no perimeter wall around the site. Sweeping vistas of the West Bank and the Mediterranean beyond are a constant reminder of connection to place.

The main exhibition room is complemented by a glass gallery, delineated by a subtle spatial shift that reveals the roof’s geometry. It looks westward across the site and to the sea, and out into a sunken outdoor amphitheater, offering a constant connection to the physical reality of Palestine — as well as a device for both national memory and global connections, honoring ongoing struggles while speaking to future aspirations.

It's within the confines of such a thoughtful national institution that curator Tina Sewell thought to pose the following questions through an exhibition (as she writes in her statement):

“How do artists negotiate and articulate collective and personal memory in relation to representations of landscape? What keeps us in a place? What are the limits of nostalgia? How does exile and different experiences of alienation shape views of the landscape? With our diminishing access to the land, the segregation of communities and the fragmentation and isolation of the terrains, and as the violent confiscation and destruction of the land unfolds, how do our intimate relationships to places manifest around landscape? Yet undeterred by this, what have been and what are our dreams and visions of landscapes of the past and future?"

The exhibition may not answer all of these important questions, but it certainly provides food for thought. And in a region where landscape was often the purview of colonial projections and imperial ambitions, Intimate Terrains performs the radical exercise of giving voice to Palestinian artists, both past and contemporary.

Motherlands and Dreamlands — the first of nine sections — offers historical context with work by Sliman Mansour and Nabil Anani. Mansour’s gorgeous 1979 oil on canvas painting Yaffa, depicting a woman in traditional dress holding a basket of just-picked oranges from an orchard, evokes loss, nostalgia, but also hope for the future with its vibrant colors and a golden landscape that sings with life.

Anani’s 1995 Motherhood, also an oil on canvas, features a maternal figure with a dress in the colors of the Palestinian flag, holding a child under a canopy of grapevines. It reads like an idealized Palestinian Mother Courage, or at the very least, a Mama Palestine sheltering a fledgling nation.

The works are typical of the landscape genre that dominated Palestinian art from the mid-1970s onwards. The pieces fuse resistance slogans with popular posters, folkloric symbols, and nostalgic images from a romanticized past, in a format that escaped the excesses of Israeli censorship.

The next section, Be-Longing, includes the work of Anani and Mansour, while also encompassing that of Jumana Emil Abboud, Yazan Khalili, and Tayseer Barakat. The section examines the artwork during the time of the First Intifada (1987-93). At that time, artists disengaged with both traditional oil painting and Israeli-supplied materials, beginning to experiment with natural materials like mud, olive oil, clay, and henna. Video also became a popular medium: The film Maskouneh (“Inhabited”) by Jumana Emil Abboud with Issa Freij is a fine example of spectral wandering through a beloved landscape, filled with longing and loss, absence and presence.

Yazan Khalili’s book, On Love and Other Landscapes, is a resonant companion piece, with its juxtaposition of landscape photography and a love story — a literal kind of intimate terrain.

Fragmentation, featuring the work of Bashir Makhoul, Hasan Daraghmeh, Sliman Mansour, and Steve Sabella, explores the fragilities of identity through works of mixed media and video. Daraghmeh’s powerful Flower of Salt uses hours of footage from refugee camps in Jericho and Ramallah, reducing the frame size until the landscape becomes a vast pixelated terrain — at once personal and abstract.

Elusive Viewpoints juxtaposes beautiful yet melancholic paintings of the Jerusalem hills by Sophie Halaby with more contemporary studies of Jerusalem. This includes a photographic revelation of past and present in Jack Persekian and Jawad al-Malhi’s photographic panorama, Tower of Babel Re-visited, examining the built environment of refugees.

Aissa Deebi’s This is How I Saw Gaza offers sobering prints of re-representations of TV news screen images of terrifying violence.

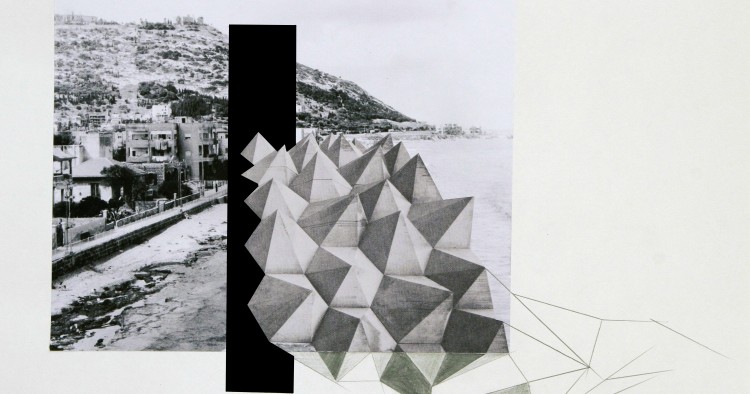

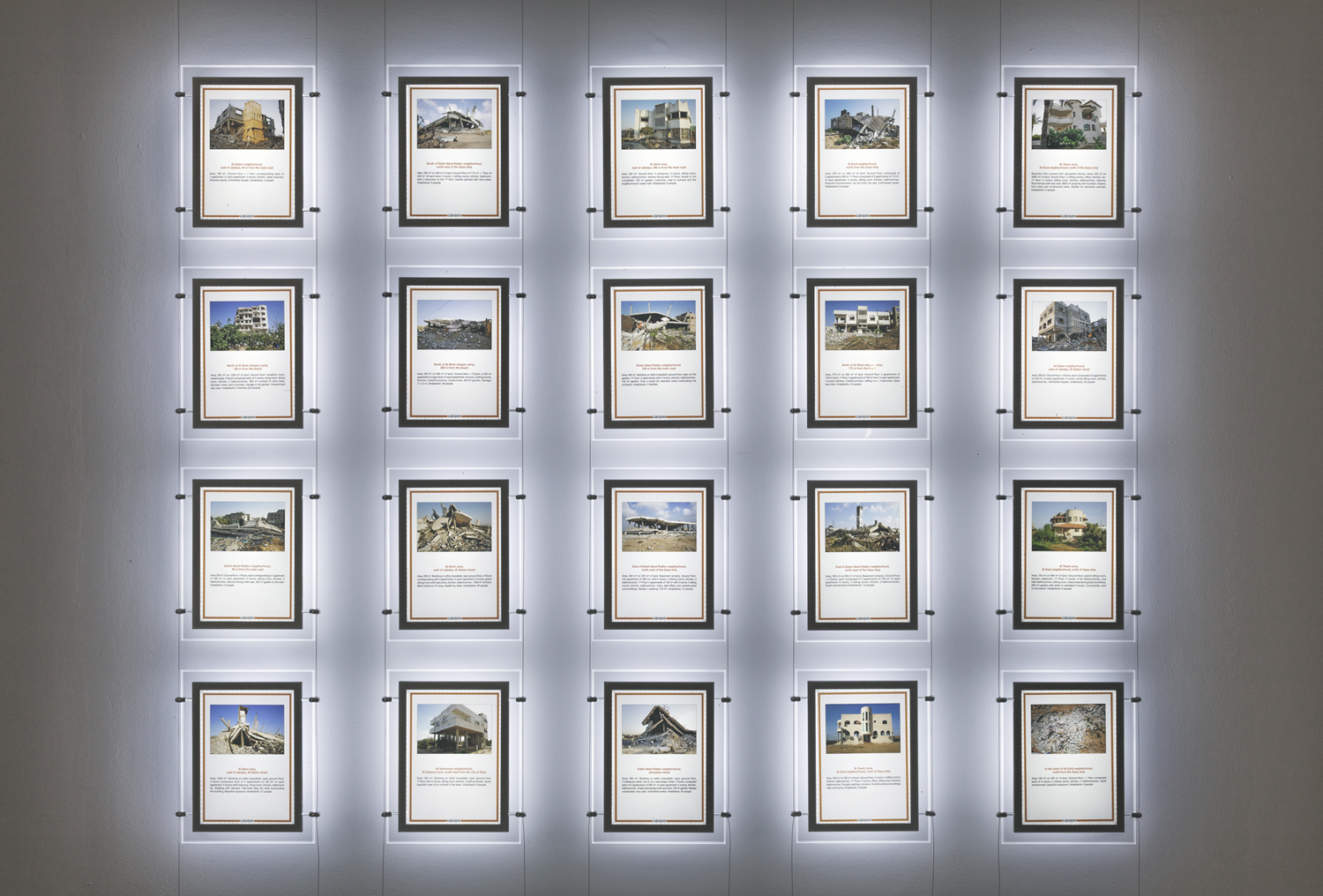

Traces of Memories includes the work of 10 artists ranging from etchings and paintings to videos that explore landscape and loss, while Archaeology of Place includes the work of seven artists that examine similar themes through a more layered, historical lens. Highlights include The Archaeology of Occupation, a series of collages by Hazem Harb combining archival photographs of pre-1948 Palestine with vaguely brutalist concrete forms floating ominously over the landscape, a reference to the Bauhaus style that worked hand in hand with military occupation, and Taysir Batniji’s GH0809#2 (Gaza houses 2008-2009), picturing homes destroyed by the Israel Defense Forces after the December 2008-09 military operation against Gaza as real estate advertisements, cleverly re-historicizing urban ruins.

The work of video artist Larissa Sansour stands out in the last two sections. In Distance and All That Remains, her video Nation Estate imagines a future Palestine as a single high-rise tower, cut off from the land, with each city a floor and Jerusalem as a theme park.

In the last section, The Unrecognizable Landscape, Sansour’s 2015 single channel digital video installation with Soren Lind, In the Future, They Ate from the Finest Porcelain, offers a thought-provoking sci-fi vision of dystopian displacement. The film, which combines live action, computer-generated imagery, and historical photographs, is set in an imagined future where the leader of a “narrative resistance” group converses with her psychiatrist about her murdered twin sister, and what prompted her quest to save her people from erasure. Using fine porcelain imprinted with the traditional kaffiyeh graphic pattern, she sets out to plant it in the soil of her homeland in the hope that some future civilization will discover it, legitimizing her people’s historical connection to the land.

Intimate Terrains is both a triumph and a testament to the heartfelt connection of artists — even those in diaspora — to their homeland, and to a landscape that may be disappearing materially, but remains a powerful spiritual reality.

Hadani Ditmars is the author of "Dancing in the No-Fly Zone: A Woman's Journey Through Iraq," a past editor at New Internationalist, and has been reporting from the Middle East on culture, society and politics for two decades. The views expressed in this article are her own.

Main image: Hazem Harb, Untitled #16 from the Archaeology of Occupation series, 2015. Digital print. Courtesy of the artist and Tabari Artspace.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.