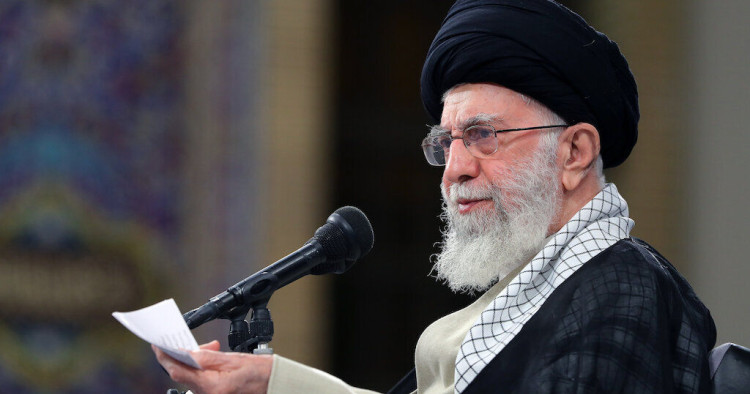

This article is the first in an ongoing series exploring the question of succession in the Islamic Republic and the eventual move to a post-Khamenei era.

On March 1, 2024, the Islamic Republic of Iran will hold elections for the sixth term of the Assembly of Experts. The major responsibility of this 88-member body is to designate the future supreme leader after the current leader’s death or when he becomes incapable of fulfilling the position’s responsibilities.

At present, there is no verified information about the health of 84-year-old Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. However, since the sixth Assembly of Experts will continue its term until 2032, this next assembly may very well be charged with designating Khamenei’s successor — if the Islamic regime continues to rule Iran until then.

The supreme leader’s role in the succession process

The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran is structured in a way that the current leader has a decisive influence on the selection of his successor. According to the constitution, all candidates for the Assembly of Experts must be qualified clerics, and their eligibility must be approved by the jurists of the Guardian Council. The Guardian Council consists of six Shi’ite jurists and six legal scholars. Each of those Shi’ite jurists is directly appointed by the supreme leader, while the council’s legal scholars are all chosen by parliament from individuals pre-selected by the head of the judiciary, himself appointed by the supreme leader. According to the election law of the Assembly of Experts, legal scholars of the Guardian Council have no right to intervene in approving the qualifications of candidates for the Assembly of Experts; this responsibility lies solely with the six Shi’ite jurists of the Guardian Council, who, as noted above, are directly appointed by the supreme leader.

In this context, the Shi’ite jurists of the Guardian Council will undoubtedly reject the qualifications of any candidates to sit on the next Assembly of Experts whose views may differ in certain areas from those of Ayatollah Khamenei.

All that said, the role of the sitting supreme leader in the process of selecting his successor will not necessarily be confined to formal processes. During his leadership, Khamenei has not only intervened in macro-level policy matters but has also consistently engaged on plenty of minor government issues as well — from vaccination regimens and television programs to sports teams and school textbooks. Many of the supreme leader’s interventions have been directly related to his growing concerns about the future of the Islamic Republic. It is nearly inconceivable that a leader accustomed to involvement in such a broad spectrum of major and minor issues would refrain from intervening in the most crucial matter related to the fate of the Islamic Republic — i.e., the issue of leadership succession.

The appointment, in August 1989, of Ali Khamenei as the successor to Ruhollah Khomeini resulted from the claim of officials like Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, the then-speaker of parliament, and some other influential figures in the Assembly of Experts, who “testified” that Ayatollah Khomeini had previously expressed interest in Khamenei succeeding him. It is uncertain whether a similar event will occur after Khamenei’s death. Nevertheless, it is unlikely he will pass away without somehow recording his opinion about those who should or should not become the next leader. If such documentation exists, quotes from Ayatollah Khamenei will play an important role in determining his successor in the Assembly of Experts.

The actual status of the assembly

In general, it should be noted that the Assembly of Experts, despite its considerable formal authority, has practically served only as an affirming body for the views of the supreme leader. According to Iran’s constitution, this assembly has the authority to supervise the performance of the supreme leader and can even remove him in the event of his incapacity to fulfill his duties or failure to meet the conditions of leadership. However, the sessions of the Assembly of Experts, which are usually held twice a year, have mainly been ceremonial occasions for members to express enthusiastic support for the supreme leader. The assembly’s “supervisory” responsibilities concerning the supreme leader have been restricted to issuing similar statements endorsing Ayatollah Khamenei’s views and praising his leadership. During Ayatollah Khomeini’s era as well, the Assembly of Experts lacked a true supervisory role in overseeing the supreme leader’s performance. Nevertheless, following the ascent of Khamenei, the assembly experienced an even greater decline in its position, becoming considerably weaker than before.

Several pivotal moments mark the evolution of the Assembly of Experts’ role. The crucial turning point took place during the assembly’s session on June 4, 1989, when Ali Khamenei was appointed as the successor to Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The first constitution of the Islamic Republic stated that the leader must be a marja-e taqlid, meaning he should have reached the highest position in the hierarchy of Shi’ite clergy. Yet at the time of Ayatollah Khomeini’s death, Khamenei did not hold such a position, nor did he even claim to have such a status. Nonetheless, advocates of his leadership orchestrated a politically motivated vote, claiming Khomeini’s preference for Khamenei’s leadership. The result was the unlawful appointment of Khamenei until a revision in the constitution took place. By endorsing a choice that was explicitly against the constitution at the time, the assembly essentially acknowledged a decline in its legal status. Then, on July 28 of the same year, the constitution underwent amendments, one of which involved eliminating the requirement of being a marja-e taqlid from the leadership criteria. Consequently, on Aug. 6, the Assembly of Experts convened a new session and elected Khamenei as the permanent leader of the Islamic Republic.

Another turning point occurred during the elections of the second term of the Assembly of Experts, in October 1990. In the first assembly’s elections, in December 1982, candidates could qualify by receiving endorsements from two senior Shi’ite clerics. However, three months before the end of the assembly’s first term, its members changed the body’s internal regulations, transferring the responsibility of approving its own candidates’ qualifications to the Guardian Council. Exploiting this power, the Guardian Council rejected a significant number of candidates from the left-wing religious faction, thereby securing the dominance of Khamenei’s right-wing allies within the next Assembly of Experts.

Yet another pivotal moment occurred during the elections for the fifth term of the Assembly of Experts in February 2016. Like previous assembly elections, the vast majority of candidates who could potentially disagree with the supreme leader were rejected by the Guardian Council. However, a coalition of political forces aligned with Hassan Rouhani and Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani organized a campaign with the goal of transforming the elections into a symbolic confrontation with the dominant clerics in the Assembly of Experts. In Tehran, the Guardian Council rejected most figures from this coalition, resulting in an insufficient number of candidates to form a complete list of 16 members. Consequently, this coalition sought to at least eliminate Khamenei’s most influential political allies from the assembly, including Mohammad Yazdi, the then-head of the Assembly of Experts, Mohammad-Taqi Mesbah Yazdi, the most prominent theorist supporting Khamenei, and Ahmad Jannati, the secretary of the Guardian Council. In the end, Mohammad-Taqi Mesbah Yazdi and Mohammad Yazdi were eliminated, and Ahmad Jannati was given the lowest position among the elected members from Tehran, while Hashemi Rafsanjani and Hassan Rouhani secured the first and third positions, respectively.

However, this campaign only achieved symbolic results. In response to the protest campaign of Tehran voters, the fifth assembly selected Ahmad Jannati as its chairman and, in practice, remained as hardline as previous assemblies. The experience of 2016 clearly strengthened the view that even the most conservative efforts to change the composition of the Assembly of Experts or possibly influence the selection of the next supreme leader are fundamentally futile. It can be presumed that this experience will be one of the factors affecting the electoral behavior of political forces and ordinary voters in the assembly’s 2024 elections.

The impact of the IRGC

Another institution that will play a decisive role in determining the future leader is the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). As the most powerful military-security force and the largest economic cartel in the Islamic Republic, the IRGC has all the necessary tools to exert influence over the Assembly of Experts and manage those few members who may not align with the majority.

It is important to consider the IRGC’s role in the process of selecting the future leader as a complement to that of the current supreme leader, not as a competitor. Although there may be dissatisfaction among some IRGC personnel with the current state of the country, the commanders of this force have been in complete harmony with the supreme leader so far. Indeed, among the government institutions in Iran, it is difficult to identify one that has benefited more from Ayatollah Khamenei’s and his predecessor’s policies or been more effective in implementing the supreme leader’s policies than the IRGC.

It is undeniable that during periods of internal divisions within the Iranian regime, when factions have held differing opinions or conflicting interests with Khamenei, the IRGC has consistently aligned itself with the supreme leader. Over the past three decades, especially during the presidencies of Mohammad Khatami and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, some analysts both inside and outside Iran speculated that there might be significant rifts within the IRGC, between supporters and opponents of Ayatollah Khamenei. However, it has been proven over time that such assumptions were baseless.

It is worth recalling that during the second term of Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani and both terms of Mohammad Khatami and Hassan Rouhani, the IRGC opposed the policies of the sitting presidents, who were accused of disobedience to the supreme leader. Even Ahmadinejad, who enjoyed the full support of the IRGC during his first term when he was entirely obedient to the supreme leader, faced severe opposition from the Revolutionary Guards after he started disobeying Khamenei on certain issues. The current president, Ebrahim Raisi, has been in complete lockstep with the supreme leader and, therefore, has not faced significant challenges from the IRGC so far.

Given these realities, it can be expected that during the selection of the next supreme leader, the role of this military force will be to consolidate the leadership of the individual favored by Khamenei, someone with whom the IRGC commanders are unlikely to have any issues.

A “leadership council?”

One imaginable scenario in the post-Khamenei era is the formation of a de facto leadership council. The likelihood of such a collective leadership is, of course, very minimal.

In the first constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the Assembly of Experts had the authority to choose either an individual leader or a leadership council consisting of three or five members. With a constitutional amendment in 1989, the term “leadership council” was removed from the text, and the Assembly of Experts was obliged to select an individual as a successor in case of the supreme leader’s death or incapacity to perform his duties. The amended constitution remains in effect to date.

However, it is conceivable that following the supreme leader’s death, circumstances may arise where, in practice, a three-member council assumes leadership tasks, even if its formal name is not explicitly stated as the “leadership council.”

Article 111 of the current constitution states, “In case of the death, resignation, or dismissal of the leader, the Assembly of Experts must, as soon as possible, take steps to appoint and introduce a new leader. Until the appointment of the new leader, a council consisting of the president, the head of the judiciary, and one of the [Shi’ite] jurists of the Guardian Council who is elected by the Expediency Discernment Council, will temporarily assume all the duties of the leadership.” It should be noted that the Expediency Discernment Council is a supreme governmental council, most of whose members are directly appointed by the supreme leader. One of its responsibilities is formulating the macro policies of the Islamic regime and presenting them to the leader for final approval.

Article 111 considers this three-member council temporary until the appointment of a new singular leader but does not specify how much time the members of the Assembly of Experts have to reach a decision, and what will happen if they fail to agree on an individual within a certain period. This issue becomes more crucial when considering that, according to the internal regulations of the Assembly of Experts, at least two-thirds of its members must vote for the new supreme leader. In other words, as long as no individual receives the two-thirds majority, the three-member council mentioned in Article 111 can indefinitely assume the leadership duties.

This three-member council can, if deemed necessary, even initiate a referendum to amend the constitution “after obtaining the approval of three-fourths of the members of the Expediency Discernment Council.”

Practically speaking, however, the likelihood of two-thirds of the members of the Assembly of Experts failing to reach an agreement on the appointment of the next supreme leader is very minimal. As emphasized earlier, the current supreme leader of the Islamic Republic naturally strives, through the Guardian Council, to ensure that individuals not aligned with his views are not members of the Assembly of Experts. Additionally, if internal disagreements do arise in the Assembly of Experts, it is expected that the IRGC will use its formal and informal levers of power to pressure the members of this assembly and compel them to choose a new supreme leader as quickly as possible.

Nevertheless, in a comprehensive analysis of the post-Khamenei era, if the Islamic Republic is not overthrown, the probability of a delayed selection of the supreme leader’s successor cannot be entirely dismissed.

Marie Abdi is an Iranian political researcher focusing on the Islamic Republic's domestic and regional strategies.

Photo by Iranian Leader Press Office/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.