In my last article, written immediately before Tuesday’s Israeli election, I noted that three right-wing rivals of Prime Minister Benjamin (“Bibi”) Netanyahu, having already realized that none of them was likely to become prime minister in this election cycle, were instead desperately trying to be kingmaker. Now, with virtually all of the vote in and results unlikely to change, it is clear: Not only will there be no kingmaker, there will probably be no king. Though parties likely to support Netanyahu do have 63 seats, that count includes a very far-right, Kahanist party (“Religious Zionism”) and an Arab party (Ra’am/United Arab List, or UAL), both of which have made it clear they would not sit in a government with each other — and each is essential for a Netanyahu majority. Thus, unless the tallies shift (conceivable), or several members of an anti-Bibi party break ranks (possible), or an attempt to disqualify Bibi from running by passing a law in the next few weeks barring indicted members of the Knesset from serving as prime minister succeeds (unlikely but possible), Israel is headed for its fifth election in two and a half years (probable), most likely in early October (summer is usually out and September is filled with holidays). It could be noted in passing that Bibi’s son, Yair, is organizing a “stop the steal” campaign on social media, which is no more likely to succeed than its American predecessor.

It's all about Bibi

While these four elections have been unfolding, however, Israel has careened from early successful pandemic precautions to a premature opening up that briefly gave it the worst infection stats in the world, to anger at widespread ultra-orthodox flouting of lockdowns to, now, having vaccinated a higher percentage of its population than any other country in the world, and almost all sectors of society reopening, conveniently right before the election. All of this was unquestionably due to Netanyahu.

Netanyahu has also been credited, even by his political enemies, with obtaining unheard-of largesse from a Trump administration falling over itself to support Israel. The U.S. recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and moved its capital there, to the applause of most Israelis. In the last year, four Arab states recognized Israel, thanks to Donald Trump’s prodding and diplomatic gifts, again chalked up to Bibi. Israel has greatly expanded its diplomatic presence, especially in Africa, under Bibi’s watch. For a country whose Jewish inhabitants still feel that the world is lined up against them, these are powerful accomplishments. Why is Bibi not reaping the political benefits?

In some ways, he has. He has now served appreciably longer than any other Israeli prime minister: one term in the 1990s and 12 years consecutively now, for a total of 15 years, even beating out Israel’s legendary founding father and first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion. In the process he has instituted policies of attacking the “elites,” who allegedly run the country. He calls out Ashkenazim (like him) who are dominant in culture, business, universities, media, and the courts, a political strategy that should sound familiar to Americans. He actually preceded by a few years the wave of populism shaking democratic countries around the world — some now “previously democratic” — and has formed close personal and political bonds with the leaders of India, Poland, Hungary, and even Russia, besides the U.S.

Domestically, Bibi has railed increasingly against “leftists,” a term that now seems to encompass all his opponents, even those generally considered to his right. He has also, until recently, railed similarly against Israel’s 1.9 million Arab citizens (21% of the country’s population), especially through passage of the 2018 “nation-state law,” enshrining in semi-constitutional status that only the Jewish people has a national right to the Land of Israel, also known historically as Palestine.

A dramatic shift among Israeli Arabs

Meanwhile, however, things have been shifting dramatically within Israel’s Arab communities: politically, socially, and economically. Netanyahu’s government has quietly been very good for them, transferring unprecedented funds to Arab municipalities. These and demographic changes are altering their structure, especially with many more women receiving higher education, having fewer children, and their families joining a new and growing Arab middle class. It is these developments (and some political ones as well) that first helped cement the Joint List, an unprecedented alliance of four highly disparate Arab parties, which ran together in two of the last four elections. In the latest one, the UAL ran on its own, with its leader, Mansour Abbas, asserting that its voters, largely poor, religious Bedouin, have more in common with the Sephardi Haredi party, Shas, than with the secular Chadash, the dominant party in the Joint List. The gambit partially paid off, with UAL having passed the 3.25% threshold for parliamentary representation to gain four seats and about to sit in the Knesset. However, it will not join a government that contains Kahanists, so Bibi is therefore denied a government.

The most important shift is that we see Israeli Arabs voting their social, economic, and religious values, instead of solely according to their Arab identity. If this trend continues, and it probably will, we are likely to see more Arabs appearing in the Knesset representing mainstream right-wing parties such as Likud, and even Arab parties like the UAL participating in future governments. This would be the Israeli domestic equivalent of the Nixon in China syndrome, in which the right ends up breaking a taboo they themselves have championed for decades.

Alternative paths

There is another route already being actively pursued by some in the anti-Netanyahu camp, namely, a new law that would effectively bar him from being chosen as prime minister as long as he is under indictment. This is the result of the fact that the anti-Netanyahu parties, which are leftist, rightist, centrist, Arab, and anti-religious, all agree on one thing only, that is, bringing Netanyahu down. They have a bare majority of 61 seats in the new Knesset, which will probably convene in early April. If they are successful, then the whole dynamic changes, with a right-wing government likely.

However, that is exactly why such a measure will probably not succeed. Much as the left may desperately wish Bibi gone, why should they clear the way for a right-wing government? Moreover, they have an ace up their sleeve, or at least a knave. According to the coalition agreement that established the current (now interim) government, Benny Gantz of the Blue and White party is scheduled to become prime minister this November under a rotatzia, or rotation, provision. Gantz now has eight seats in the new Knesset, a respectable showing, given that he seemed down and out only a few months ago. This would presumably be after a new (fifth) election but before a new government could form, unless the right manages to form one in record time to forestall this.

What’s next?

It must be emphasized that Israel appears to have moved decisively to the right. Right- wing parties received either 79 or 83 seats, depending on whether UAL is considered “right wing.” Exploiting this strength is prevented primarily by the divisive figure of the current prime minister, who, although going strong, is 71 years old and can’t continue forever. My own guess is that once he is eventually removed from the equation and the left can find a leader and a set of popular policies (admittedly, neither is an easy task), Israeli politics will resume a more normal left-right orientation. The left’s holy grail is formation of an “Arab-Jewish party,” drawing support from both ethnicities. That remains elusive.

Amid all this politicking, it seems to have been forgotten that the purpose of any election is to generate a government that will actually produce and implement policy. An interim government is prohibited by law from taking new initiatives except in an emergency. As has frequently been pointed out, the current series of campaigns has completely ignored Israel’s main existential concern, namely the Occupation and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, which are not going to be resolved no matter how many Arab states Israel signs treaties with. The left sees a serious erosion of democratic norms, while the right decries legal, educational, and financial elitism. Inequality is a major issue, with Israel having gone from being one of the world’s most economically egalitarian countries to one of the most unequal, with more billionaires per capita than anywhere else. Israel is also staunchly against resumption of both the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action with Iran and movement on the two-state solution, both of which are declared priorities of the Biden administration. Biden has not yet pressured Israel or brought up these issues, presumably waiting until a new government is formed, but it will not wait forever. None of these issues are being addressed while the political class — and much of the country at large — is consumed by political maneuvering.

The future is not determined — and perhaps even these results could produce something other than a stalemate and a new election. Israel seems to have emerged successfully from the pandemic and is managing to function even without a normal government, but cannot do so forever. However, the country enters its spring holiday season on Saturday night with the beginning of Passover, followed by Memorial Day, Independence Day, and continuing until the religious holiday of Shavuot on May 17. Between holidays and a long pent-up need for travel and vacation, the political class will try to form a new government within about two months. My guess is they will fail.

See you in October.

Paul Scham is a scholar at MEI and the director of the Gildenhorn Institute for Israel Studies at the University of Maryland, where he teaches courses on the history of Israel and of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The opinions expressed in this piece are his own.

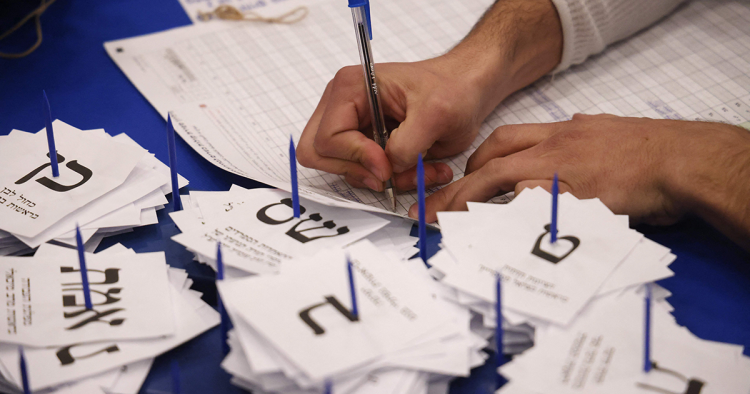

Photo by EMMANUEL DUNAND/AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.