Palestinian Authority (PA) officials repeatedly deny acquiescing to the economic peace model with Israel, but such rhetoric is not reflected in their actions. In recent years integration between the Palestinian and Israeli economies has only deepened.

For the PA, economic integration with Israel — through the implementation of the Oslo framework — provides much-needed revenue for its coffers and sustains basic economic activity. The PA operates within an inherently distorted economic structure; Palestinian economic dependency on the more competitive and technologically superior Israeli economy is deeply rooted in an Israeli colonial economic system of control that derives its power from several forms of market dependency as well as complete control over economic and fiscal incomes. Economic agreements created with the establishment of the PA have only institutionalized these colonial economic systems.

For a brief period, there were hopes that the PA would change course and pursue an independent economic path. In response to Donald Trump’s so-called “deal of the century,” the PA escalated rhetoric calling for economic disengagement from Israel. By 2019, it became apparent that a new Palestinian prime minister with stronger economic credentials and a higher profile among international donors was needed to address the PA’s mounting fiscal struggles. In March 2019, Mohammad Shtayyeh, an economist, became prime minister, with the primary objective of correcting the dismal economic and fiscal position of the Palestinian economy.

Shtayyeh quickly announced an economic development plan based on disengagement from Israel. The PA’s National Development Plan for 2021–2023 emphasized disengagement as a means of imposing independence as a fact on the ground. Shtayyeh’s strategy seemed to be based on three pillars: fostering sector-specific development programs, such as for agriculture and tourism, to leverage the competitive advantages of each region in the West Bank; seeking alternative business partners to replace trade with Israel; and building the foundation for a knowledge-based Palestinian economy that could complement the other pillars. However, while Shtayyeh has publicized progress toward partial implementation of the three pillars, and while his plan may be well thought out, actually reducing economic and fiscal dependency on Israel remains contingent on the political situation and, therefore, on Israel’s cooperation.

At the heart of the PA’s failure to economically disengage from Israel is the Palestinian economy’s near total dependence on external sources of income. As explained elsewhere for the Middle East Institute, economic dependence on Israel is built upon a trinity of external or recycled income streams — namely, international aid disbursements, remittance flows from Palestinian workers in Israel and settlements, and clearance revenue transfers, tax collected by Israel that is transferred to the PA on a monthly basis — that have come to define the Palestinian economy and that determine the PA’s financial health. Recent changes in aid levels to the PA and anticipated changes to how Palestinian workers in Israel receive their pay are likely to have a significant impact on the Palestinian economy in the coming years and further impede the PA’s disengagement plans.

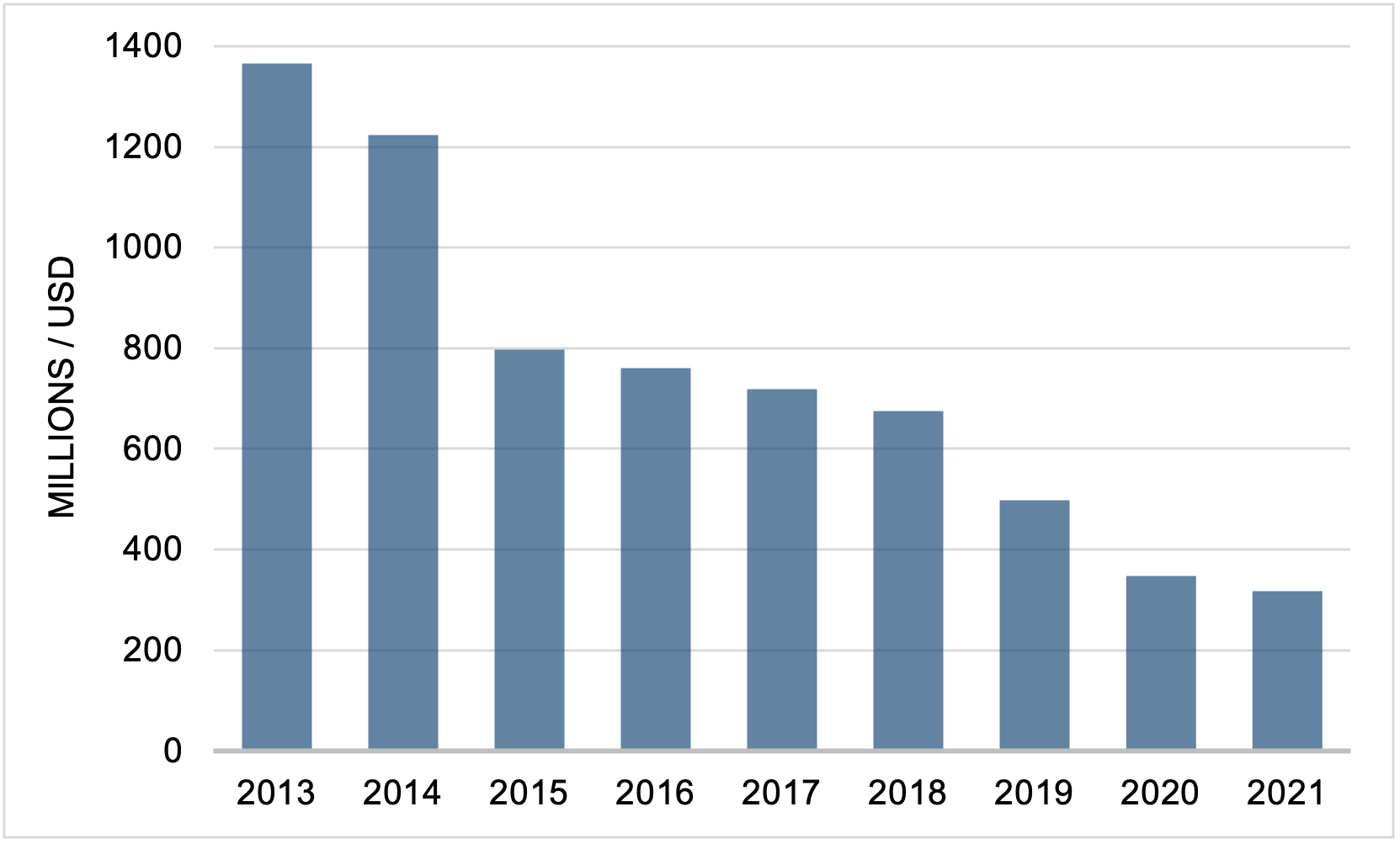

Shtayyeh’s disengagement plan is laden with calls for the restoration of international aid to previous levels as a necessary condition for implementing the PA’s disengagement strategy. Despite these calls, the PA has failed to convince international donors to funnel their funding through its budget. More than $41 billion in international aid has flowed to the West Bank and Gaza since 1993. For years, aid represented the backbone of economic activity and supplied the PA with necessary income in the absence of other funding options. Until recently, the PA coffers were the primary destination for aid; about 40% of all aid disbursed in Palestine since 1993 has ended up in the PA budget. However, recent years have seen a sharp fall in donors’ willingness to directly fund the PA, despite aid levels to the wider Palestinian economy stabilizing at around $2 billion for several years. As Figure 1 below shows, aid disbursed through the PA budget has fallen to only $318 million in 2021, a 77% decline since 2013.

Figure 1: International aid to the Palestinian Authority's budget

Dwindling aid is forcing the PA to search elsewhere for revenue to sustain its expenditures, which are growing at a rate of 7% annually. The PA’s fiscal deficit is also expanding uncontrollably, driven by a ballooning wage bill that accounts for 44% of total PA expenditure. Expenditures in 2021 are projected to have reached $5.4 billion, greatly exceeding revenues at $3.7 billion. In order to bridge this $1.7 billion deficit, the PA has taken a clearance revenue advance from the Israeli government of about $153 million in addition to the projected $318 million in aid, leaving the PA with a deficit of $1.23 billion. The PA is expected to bridge this gap by accumulating arrears against services it receives from the private sector, as well as paying its employees partial salaries.

The PA’s search for revenue is driving it to expand its economic control over different segments of the Palestinian economy. In a move that will likely further entrench the PA’s economic dependence on Israel, the PA has announced an agreement with Israel about transferring the salaries of Palestinian workers in Israel to Palestinian banks. In contrast to the previous arrangement, under which wages were paid in cash or transferred through Israeli banks, the new agreement will see workers’ salaries deposited in Palestinian banks after Israel has deducted income tax and social security contributions. Income taxes form a portion of the clearance revenue transfers and are transferred to the PA after deducting 3%, while social security contributions are largely retained by Israel.

The expected transfers are significant for the small Palestinian economy. The Palestinian Monetary Authority (PMA) estimates that workers in Israel inject about $5.5 billion into the Palestinian economy annually, the equivalent of about 35% of GDP. The post-COVID-19 economic recovery in Israel has seen a significant increase in the number of Palestinians working in Israel and the settlements, from 125,000 in 2020 to 146,000 in 2021. With average daily wages in Israel double those in the West Bank, the incomes of these workers is expected to increase.

Given the stifling financial crisis facing the PA, transferring these funds to Palestinian banks — an arrangement requiring close cooperation between the PA and Israel — offers a short-term fix for the PA’s fiscal woes while reinforcing the underlying dependencies inherent in the political and economic structures of the PA and Palestine. In the short term these transfers may prove to be a boon for the PA and Palestinian banks, for three reasons.

The first is that these transfers are meant to address yet another financial crisis that has affected the Palestinian economy. The Israeli Shekel surplus in the Palestinian economy has reached unprecedented levels. The New Israeli Shekel (NIS) was established as the official currency of the West Bank and Gaza Strip as part of the economic agreements created with the establishment of the PA. Per these agreements, excess amounts of NIS due to balance-of-payments flows are returned to Israeli banks. However, those banks have been significantly reducing the amount of NIS they allow Palestinian banks to transfer, resulting in the accumulation of billions of NIS by Palestinian banks and the PMA.

The NIS oversaturation in the Palestinian market is caused primarily by the wages of Palestinian workers in Israel and settlements. The PMA hopes that by having these salaries deposited into Palestinian banks, Israeli banks will no longer be able to refuse NIS transfers on the basis of “uncontrolled cash,” having transferred them to the Palestinian economy.

The second reason is that transferring workers’ salaries could bring the PA one step closer to collecting taxes on a large flow of income. It is true that the PA — at least at this stage — has assured workers “there will be no double taxation” or additional fees deducted from their salaries. But the PA’s recent record illustrates its expanding domestic tax collection efforts as it looks inwards for new sources of revenue, including proposing wide-ranging tax reforms and introducing new fees and taxes. It remains to be seen whether the PA will keep its promises on worker’s salaries.

Finally, for Palestinian banks the transfer of workers’ salaries presents a major business opportunity to boost the banking rate of a traditionally unbanked segment of society. By the end of 2017, only 25% percent of adults in the West Bank and Gaza Strip had a basic bank account. Under the new agreement, Palestinian banks will see an automatic expansion of their clientele base and overall deposits.

Increased deposits of Palestinian banks would also benefit the PA by allowing it to increase its borrowing limits from domestic banks. As of August 2021, PA borrowing from domestic banks was $2.5 billion, standing at 23% of total banking sector credits. Moreover, banks’ exposure to the PA is compounded by private borrowing by PA employees; together, these two sources represent 40% of total banking sector credits.

For workers, however, the diversion of their salaries to Palestinian banks creates yet another hurdle between them and their hard-earned income. Workers already face a restrictive and complex web of regulatory, security, and bureaucratic steps to work in Israeli markets. From applying for a security clearance, to acquiring special labor permits, to paying secondary Israeli and Palestinian permit agents, working legally in Israeli markets is a very expensive and treacherous venture.

These economic developments continue the trend of the PA seeking new sources of funding — or control over additional income — through cooperation with Israel or by receiving income historically collected and handled by Israel independent of the PA. Regardless of the short-term fiscal benefit, therefore, and contrary to the rhetoric of disengagement, the new agreement on wages only entrenches the PA’s inability to mobilize domestic revenue streams and emphasizes its failure to convince Palestinians themselves to fund its budget and operations. The PA is caught in a trap. Sustaining and strengthening economic integration with Israel provide much-needed revenue. But failing to secure an alternative economic and financial structure will continue to entrench its dependence on Israel and further diminish the national base of a Palestinian economy.

Dr. Anas Iqtait is a Lecturer of Economics and Political Economy of the Middle East at the Australian National University in Canberra, a Non-Resident Scholar at MEI, and the founder of the Near East Policy Forum. He specializes in the political economy dynamics shaping governance and fiscal policy of the Palestinian Authority, and the political economy and geoeconomics of the wider region. The views expressed in this piece are his own.

Photo by Palestinian Prime Minister's Office/Handout/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.