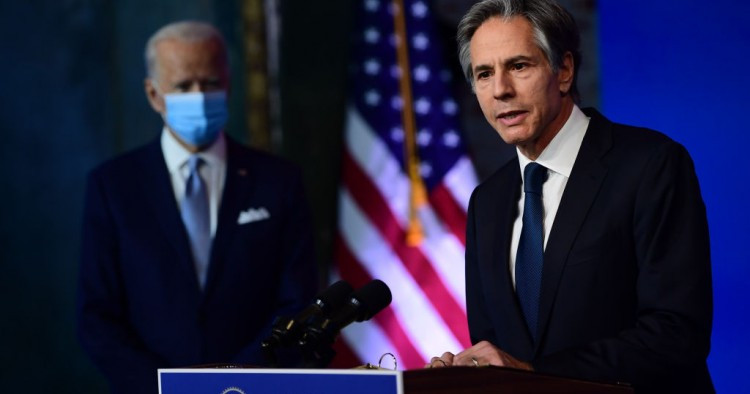

What U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s letter to Afghan President Ashraf Ghani makes clear is the declining domestic support in the U.S. for continued military involvement in Afghanistan. With his message, Blinken also signaled the demise of the Doha negotiations between the Afghan Taliban and the Afghan government and the start of a new phase. Facing domestic political disagreements and the Covid-19 pandemic, the Biden Administration was left with no option but to finalize and implement a viable Afghan strategy. For Afghans, this is a matter of utmost importance.

Blinken has suggested setting up two mechanisms to end the war in Afghanistan: First, a regional conference under the auspices of the United Nations with the foreign ministers of six countries – the U.S., Russia, China, Pakistan, Iran, and India – to discuss a “unified approach” to the conflict. Second, a dialogue in Turkey between the Taliban and the Afghan government.

While many parties are invested in a political settlement that could de-escalate hostilities in Afghanistan, the Taliban’s growing sense of leverage at the negotiating table as well as its refusal of a ceasefire threaten to thwart such an outcome. One party that is interested in de-escalation is Russia. While this goal may be shared by Washington and Moscow, the two governments have widely differing views on how to deal with the Taliban, who should lead the negotiations, and where they should be held. Over the last few years, Russia has been conducting an Afghan peace process, parallel to and often at the cost of the one shepherded by the U.S. Russia’s policy has taken a conciliatory approach toward the Taliban as part of its hedging strategy to form good relations with multiple groups that could gain power in the tumult likely to ensue from an eventual U.S. withdrawal. Given the U.S.’s harder line against the Taliban, Russia will, in all probability remain excluded from Biden’s Afghan policy.

The recent proposal presented by Blinken is a clever attempt to gain an advantage over Russia. Since 2015, the Kremlin has been engaging the top leadership of the Afghan Taliban as well as prominent Afghan political figures opposed to the Ashraf Ghani government. Therefore, an important objective of the U.S. plan to shift negotiations to Istanbul is to prevent Moscow from becoming the main venue for negotiations. At the same time, by shifting the venue from Doha to Istanbul, and thus involving Turkey in the process, the US is attempting to appease Ankara. Turkey as the facilitator for intra-Afghan dialogue is beneficial for the U.S. because the former enjoys stable relations with Iran, China and Russia. Moreover, Turkey is a Muslim-majority country and a member of NATO, factors that are crucial in terms of the conflict resolution process in Afghanistan. The U.S. might be expecting that Turkey can help connect all Afghan factions and impress on them the need to reach a deal within a short timeframe. Given Pakistan’s close proximity to Turkey — they have strengthened their military and defense cooperation in recent years — Islamabad would also welcome the change.

The Biden administration may be giving an indirect signal about India-US-Russia trilateral dynamics. In order to achieve its strategic interests in Afghanistan, India has been trying to strengthen ties with traditionally friendly countries, particularly Russia and Iran. New Delhi has often considered Russia an ally in its Afghan calculations. India may have also nurtured the hopes of being included in the crucial first phase of negotiations, but it is obvious that Russia is not keen on India’s participation at this stage and New Delhi would only have a place at the table at a later point when regional powers would get involved. However, there is another version of India’s staying away from conflict resolution activity in Afghanistan for all these years. According to Ram Madhav, a political figure close to the ruling establishment in New Delhi, India “would display righteous indignation at being excluded from the Doha talks, but privately, the leadership was happy to be out of the quagmire.”

Last month, India’s foreign secretary Harsh Vardhan Shringla met Russian officials in Moscow, holding political consultations on multiple issues including the Afghan crisis. During his speech at the Russian Diplomatic Academy on Feb. 17, Shringla noted that the “rise in violence and targeted killings of Afghan activists is not conducive to the ongoing peace process. [Indians] have advocated immediate and comprehensive ceasefire since talks and violence cannot go hand in hand.”

But Moscow has only worked with India in a very limited capacity, with a key reason being India’s official reluctance to engage the Taliban. Though India has expected Russia to pursue policies in Afghanistan that would respect New Delhi’s sensitivities, there seems to be no credible evidence that Moscow considers India indispensable to create a strategic space for itself in Afghanistan. In February 2017, India was represented when Moscow hosted consultations with six countries – Russia, Iran, China, India, Afghanistan and Pakistan. These consultations themselves featured an expanded group of participants after Afghanistan protested its absence from a December 2016 gathering of Russia, Pakistan and China. Moreover, Russia’s growing closeness with Pakistan, India’s archrival, has complicated India’s calculations in Afghanistan. Moscow has taken great pains to position itself as a friend of Islamabad, but one is also left wondering if Russia can influence Pakistan’s behavior in Afghanistan.

No country can afford to disregard Pakistan when devising Afghanistan policy. That is why Russia’s Presidential Special Envoy for Afghanistan, Zamir Kabulov visited Pakistan last month to meet Pakistan’s army chief General Qamar Javed Bajwa and foreign minister Shah Mehmood. After meeting with Kabulov, Qureshi remarked that Pakistan and Russia share a desire for “an inclusive political settlement (to) the conflict in Afghanistan.” On the other hand, Kabulov said that Russia would convene a meeting in Moscow involving the U.S., China, Iran, and Pakistan with the hopes of reaching a ceasefire. But Kabulov’s proposal met with either indifferent or hostile responses from other key stakeholders. In particular, Kabulov’s remark that the Taliban adhered to the Doha deal must have irritated Washington, Kabul and New Delhi

Russia’s increased diplomatic activism on the Afghan front may have increased the urgency in Kabul to keep the Russians in the loop. Afghan Foreign Minister Haneef Atmar went to Moscow for a three-day visit on February 24-27. During this high-profile visit, Russia’s Foreign Minister, Sergey Lavrov, asked the Taliban “to respect the already agreed-upon terms and conditions for holding direct intra-Afghan talks, and not to put forward any new preliminary requirements.” This was a significant statement from Moscow, which has hosted the Taliban many times. Although Lavrov did say that Russia “will continue our contacts with the key external players, which include the United States, China, Pakistan, India, Iran, and the Central Asian countries,” he echoed Kabulov’s formulation that Russia’s diplomatic effort in Afghanistan will mainly involve the “expanded troika – Russia, the US and China – with Pakistan’s involvement.” Since Moscow and Islamabad have come to enjoy an increasingly cozy relationship, they might view the Afghan endgame in a similar fashion — without Ashraf Ghani and with substantial representation of the Taliban. However, there is a major point of divergence between their respective positions: Russia would be dismayed to see all of Afghanistan governed by the Taliban alone, whose rhetoric on the Islamic Emirate has not been endorsed by Moscow.

If, however, Russia’s exclusion of India from the proposed Moscow talks was a tactic to appease Pakistan, the Biden administration’s proposal seeks to include India in the revamped format. By involving India in the UN format, Washington has sent a clear signal to New Delhi that America, not Russia, is more inclined to help India preserve its interests in Afghanistan.

One could argue that Russia’s policies toward Afghanistan seem to be dictated not only by a desire to help end the conflict, but also to shore up Moscow’s geopolitical position by turning Afghanistan into a bargaining chip in Russia-U.S. relations. Therefore, Moscow’s support for India’s aims in Afghanistan is likely to depend on U.S.-Russian relations. As Russia’s relationship with the U.S. is likely to remain strained for the remainder of Putin’s tenure and Moscow will likely to gravitate towards China, New Delhi’s dependence on Washington for the protection of it interests in Afghanistan will grow further. To make matters worse, India already maintains an uneasy and tense relationship with China, which is seeking to undermine India’s position in South Asia and beyond. China’s anti-India stance was reflected recently in Beijing’s aggressive stance over a border dispute. However, the Biden administration’s policy statements and actions clearly indicate that it is determined to continue developing a strong strategic partnership with India to contain China’s growing assertiveness.

Nevertheless, India clearly feels that its position in Afghanistan is challenged by others, above all by Pakistan, which regards it as an implacable enemy. This highlights the central contradiction of India’s position. India has consistently backed an Afghan-led and Afghan-controlled peace process, emphasizing that gains made in the past two decades must be preserved at all costs. In addition to supporting Ashraf Ghani, India has also made serious attempts to reach out to its traditional allies in Afghan political circles. To this end, important figures from both countries have made trip to consolidate ties. Afghan leaders Abdullah Abdullah, Abdul Rashid Dostum, and General Atta Mohammed Noor visited New Delhi last year; India’s National Security Advisor, Ajit Doval, traveled to Kabul in January 2021 to consolidate Indo-Afghan ties. These political interactions are part and parcel of India’s multi-layered geopolitical balancing and should therefore be seen as compensating for its marginal role in the peace process. The U.S. Special Representative for Afghan Reconciliation, Zalmay Khalilzad, who has retained his position from the Trump Administration, telephoned India’s External Affairs Minister, S. Jaishankar, to “discuss latest developments pertaining to peace talks.” As some elements in the Biden Administration’s Afghan package are unacceptable to Kabul (particularly interim power-sharing arrangements), Khalilzad might ask India to play a constructive role in persuading President Ghani to moderate his views. But it will be extremely difficult for New Delhi to get involved in such a touchy issue.

By inviting India to become a member of the crucial UN-mandated grouping on Afghanistan, Washington has both underlined New Delhi’s important role and given Kabul an ally in the room that could advocate for its interests. But despite the Biden administration’s tactic to involve India in its exit strategy, New Delhi has few credible options to preserve its own interests in Afghanistan because Washington is still banking on Islamabad to deliver on the Taliban.

Vinay Kaura, PhD, is a Non-Resident Scholar with MEI's Afghanistan & Pakistan Program, an Assistant Professor in the Department of International Affairs and Security Studies at the Sardar Patel University of Police, Security, and Criminal Justice in Rajasthan, and the Coordinator at the Center for Peace and Conflict Studies in Jaipur. The views expressed in this piece are his own.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.