Countries around the world are increasingly prioritizing a strict definition of sovereignty and tending toward transactional diplomacy. This global trend is shaping North African policies as well, with those governments, just like many others, emphasizing sovereignty by pursuing bilateral negotiations over multilateral arrangements, prioritizing economic self-reliance and more flexible trade agreements, as well as seeking concrete short-term benefits rather than broader, more open-ended relationships. This shift is frustrating longstanding Western interests in the Maghreb; however, it need not mean the end of existing partnerships. Understanding the motivations behind North Africa’s “sovereignty-first” approach can help the United States and Europe build mutually beneficial and durable links with the region in this new reality.

The global context and Western countries

The shift from multilateralism to prioritizing sovereignty is unmistakable in the US, where the administration has focused first and foremost on unilateral American interests. During his first term, President Donald Trump withdrew from the Paris Agreement on climate change and adopted unilateral trade practices that weakened the World Trade Organization (WTO) under the banner of “America First.” His second term began with withdrawing from the World Health Organization and various other United Nations agencies along with threats of tariffs against the US’s closest trade partners.

While this shift is more identified with Trump, President Joe Biden also sought to assert US sovereignty at the expense of trade cooperation and compromise in multilateral organizations. Biden notably maintained most of the trade restrictions his predecessor had put on China. The administration also focused its economic agenda on domestic manufacturing, as exemplified by the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which specifically favors American producers of clean energy technology over imports of such technologies from abroad. Though an economic recovery and employment boosting measure, the IRA was in part motivated by the experience of COVID-19. The pandemic had disrupted transnational supply chains, revealed the risks of overdependence on global networks, and thus prompted countries around the world — including the US — to rethink their economic strategies. With those lessons about overdependence on foreign trade partners in mind, the Biden administration also launched the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity in 2022, opting to create a more flexible and less binding strategic alliance framework.

The United States is hardly alone in choosing this more self-reliant and unilateral approach. Governments around the world are increasingly prioritizing domestic production and local supply chains. The European Union for its part is adopting “Strategic Autonomy” — broad policies meant to reduce reliance on external partners, including the US, in sectors like defense and trade. Illustratively, the EU established the European Defense Fund, to support European defense industry development through a €7.8 billion fund; and more recently, it announced the €800 billion Readiness 2030 plan, designed to further the bloc’s efforts to boost its defense infrastructure. Likewise, the EU’s Raw Critical Materials Act of 2023 looks to reduce dependence on Chinese minerals for green energy. And the REPowerEU initiative intends to likewise move Europe away from a dependence on Russian natural gas by diversifying supplies and incorporating more renewable energy.

These policy shifts reflect a broader retreat from multilateral frameworks in favor of more controlled economic relationships. New terms mask old instincts. The Biden administration focused on “friendshoring” — developing key economic relationships with friendly countries. Europe promotes “nearshoring” — developing key economic relationships with nearby countries. Both, in turn, accelerated the more general move away from multilateral cooperation toward networks of bilateral partnerships.

North Africa’s priorities

Although the European Union speaks about shared goals of “stability, prosperity, and security” in its official statements regarding North Africa, the countries of the region, including Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia, see actual EU policies as serving only Europe’s needs, especially on migration and security. In response, North African leaders are putting their own countries’ sovereignty needs first to renegotiate these relationships with Europe on more favorable terms.

Notably, North African governments have come to appreciate the leverage they have in this relationship given that the EU’s foremost priority toward their region has long focused on migration controls. Thus, in 2023, Tunisia struck a new, €1.7 billion migration deal with the EU that features funding it can use to boost the national budget, specific financial outlays for aspects like border control, and some investment in sectors that Tunis itself has identified as important. Mauritania reached its own migration agreement for €210 million in 2024, also with some more flexible spending terms.

These targeted, single-issue deals are becoming a more dominant feature than broader mechanisms like the association agreements, which were ostensibly centered on a shared vision of political and economic reform based largely on European models. Despite being nominally tailored to each country, those older frameworks imposed similar reform requirements and governance standards across different North African countries, at times with limited appeal to local constituents and priorities. North African governments often found these frameworks too rigid and insufficiently responsive to their specific needs. The newer, more transactional agreements allow these countries to secure concrete benefits while maintaining greater control over their domestic policy choices.

Beyond its relations with Europe, North Africa faces both risks and opportunities from a simultaneously unfolding global phenomenon: the weakening of multilateral institutions by the growing unilateralism of its member states, which frustrates international cooperation. For example, while this trend may reduce external financial support, it also creates space for more independent policy choices. Thus, international financial institutions increasingly face challenges to their legitimacy on two fronts. First of all, countries like Tunisia and Egypt, which have long relied on assistance from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), find themselves in a bind because available loans from those institutions come with restrictive economic and political conditions. Such loan requirements force painful reforms that cause domestic backlash against the ruling governments and accumulate debt, putting long-term constraints on national sovereignty. Second of all, more governments have been willing to look at other options, including ones involving business-minded partners. In 2023, the Tunisian president rejected an IMF loan package in favor of bilateral alternatives and domestic borrowing. Another example has been Morocco’s gradual shift toward Gulf investment and funding rather than relying on EU development aid, which came with strings attached or never materialized.

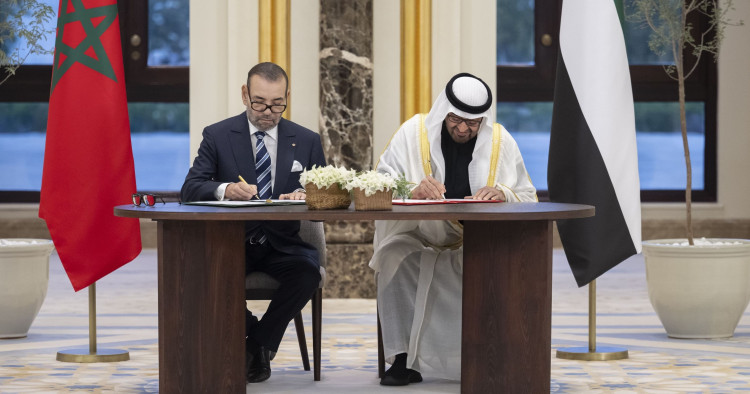

Other policy areas also reflect these changes, with governments emphasizing sovereignty by pursuing bilateral negotiations, prioritizing domestic production, reaching out to a more varied set of international partners, and seeking more immediate concrete benefits. Morocco has diversified its foreign weapons purchases as part of the country’s new, bilateral engagement with Israel stemming from the 2020 Abraham Accords. In turn, Algeria is boosting key arms imports from Turkey and China to balance its long-standing Russian partnership. Countries like Tunisia have adopted nationalist economic policies, such as placing restrictions in 2022 on a number of consumer goods imports.

For the region, domestic backlash against the imbalanced relationship with the West plays a considerable role in shaping public opinion toward sovereignty. North African countries are increasingly viewing Sino-Russia cooperation as a preferable model because it appears as more equal. Algeria and Egypt have each deepened their relations with China, drawn by Beijing’s lack of political conditions on loans and arms deals. These transactional arrangements offer what those regional countries often need — infrastructural investment, trade, and military technology — without an obligation to carry out difficult political or economic reforms in return. While this strategy may create long-term dependencies, it does provide tangible benefits without immediate sovereignty costs.

A strong populist current in Tunisia both drives and is reinforced by this shift, providing domestic support for asserting independence from international institutions that many Tunisians see as unfair or ineffective. Historically, anti-colonial sentiment has shaped North African populism. However, recent nationalist movements have also incorporated concerns about foreign influence, migration, and economic sovereignty — trends seen globally, including in Western strands of populism. In 2023, Tunisia launched a crackdown on sub-Saharan migrants, characterizing it as a response to an alleged criminal project to “change Tunisia’s demographic composition.” Morocco’s economic protectionism is another example of a shift in direction in the region. This too suggests that future cooperation with North African countries is more likely to succeed when framed in terms of concrete, mutual benefits rather than shared universal values or institutional frameworks.

The benefits of a new approach

Given these changes, North African countries now favor limited deals with specific advantages over open-ended partnerships. Past experiences with conditional aid and broad political agreements that failed to deliver tangible results have made North African governments more pragmatic. Rather than long-term commitments tied to required reforms, they now seek specific result-oriented agreements — whether on energy, infrastructure, or trade.

If the US and EU are willing to adjust how they work with the region, several areas will remain promising for future cooperation. The US, EU, and North Africa share interests in reliable energy — whether that includes natural gas or solar and wind power — as well as minerals for electric vehicle (EV) batteries and manufacturing capabilities. These overlapping needs provide a clear basis for project-based cooperation.

Cross-border infrastructure within and to North Africa presents another opportunity. Projects connecting the region through transportation corridors, energy networks, or water management systems are attractive. They facilitate access and movement for all. These are just some examples of practical mutual interests that could provide a solid foundation for joint activities in the coming years. As countries focus more on transactional benefits, they can also be clearer about what they truly need from each other. Cooperation in these specific domains may be more durable when each country can clearly see the gains.

Intissar Fakir is a Senior Fellow at the Middle East Institute.

Photo by UAE Presidential Court / Handout/Anadolu via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.