For decades, the space sector has been an important way for select countries to demonstrate their ability to operate in a highly technical, expensive, and elite arena, thus showcasing their power in politics and commerce. While the United States, China, Russia, Japan, and France are established leaders in space, with large budgets and a track record of accomplishments, new players are emerging with bold ambitions. In 2022, South Korea became the tenth country to conduct an orbital launch. In the Middle East, the Gulf states — working together and on their own — are also looking to achieve new scientific and commercial breakthroughs in various areas of the space industry. These ambitions carry major geopolitical implications with them, as an ever-growing number of spacefaring countries negotiate a sensitive and increasingly high-powered sector.

As of 2022, the U.S civil space budget (almost $24 billion) represented over 40% of the global total and was about double that of second-place China. However, in that same year, the number of national space agencies around the world reached approximately 70. There are more countries with seats at the table in terms of space activity than ever before, and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) is eager to play a prominent role in this field. In fact, with their abundant resources and clear priorities to diversify their economies across forward-looking technologies, the space business strongly aligns with the objectives of the GCC member states. Furthermore, achievements in space are a meaningful way for GCC states to increase their national brand.

Saudi Arabia played a leading role in the first Arab satellite launch in 1985, conducted by Arabsat. While Arabsat was created by the Arab League as a whole, its headquarters is in Riyadh, and the Saudis are its largest shareholder by a sizable margin. In that same year, Prince Sultan bin Salman Al Saud, the son of the current Saudi monarch, King Salman, became the first Arab astronaut.

Just like in other sectors, the GCC’s largest economy, Saudi Arabia, is today asserting itself with an ambitious new approach to space. In 2020, Saudi Arabia announced a $2.1 billion allocation to its space program as part of the diversification efforts outlined in the Saudi Vision 2030 strategic framework. The Saudi Space Commission unveiled plans for the Saudi Space Accelerator Program at the end of 2022. Then, in February 2023, the Saudi government selected two Saudi astronauts to go to the International Space Station (ISS) later in the year on a mission led by the American company Axiom Space.

Saudi Arabia’s Communications, Space, and Technology Commission stated that the national space strategy will be released in 2023. Priority sectors for Saudi space activity include tourism, photography, satellite communications, and exploration. Although they are in an earlier stage of their space sector development than the Emiratis, the Saudis are now moving fast and demonstrating their intention to become a major spacefaring country.

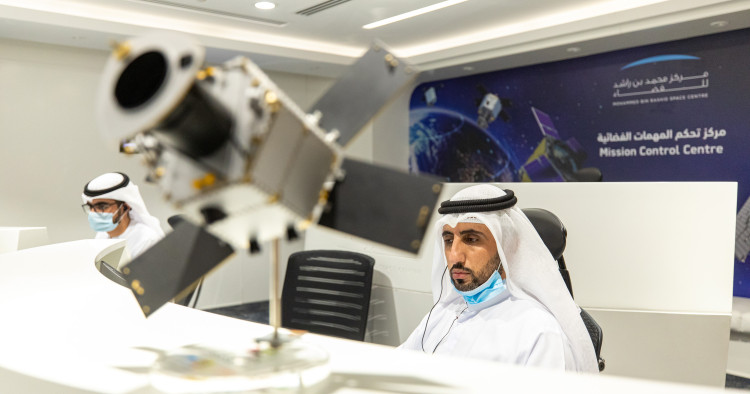

In recent years, the United Arab Emirates has made a big push, with the inflection point being the release of the National Space Strategy 2030, approved by the country’s cabinet in March 2019. The strategy outlines plans to develop a national space policy, open four space research and development centers, and establish national space laws and regulations.

In 2021, the UAE’s Hope Probe entered orbit around Mars, making the United Arab Emirates the first Arab state and the fifth country globally to accomplish that task. The following year, the UAE announced a more than $800 million National Space Fund designed to “build national capabilities and competencies, raise the economic contribution to diversifying the national economy, and consolidate the UAE’s position in the space sector.” In terms of an articulated strategy with funding tied to it, the UAE is the most developed space sector player in the GCC.

At the end of 2022, the Rashid Rover, the first Arab-built lunar spacecraft, was launched from the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station. Additionally, Sultan al-Neyadi embarked on the first long-duration mission flown by an Emirati astronaut when he arrived at the ISS in early March 2023 (the first Emirati astronaut to go to space was Hazzaa al-Mansoori in 2019). Some of the country’s plans for space are longer term and more aspirational, with the Mohammed bin Rashid Space Center and related entities aiming to construct a human settlement on Mars by 2117.

While the Emiratis and Saudis represent the majority of GCC space activity today, other member states are taking noteworthy steps as well. In recent months, Qatar’s Es’hailSat satellite company inked a strategic partnership deal with Axess Networks, and U.S. Central Command held its first space forum at the al-Udeid Air Base in Qatar.

In turn, Oman is home to the GCC’s most advanced satellite monitoring station, used to help with the regulation of satellite communication signals; and Oman’s sovereign wealth fund, the Oman Investment Authority, invested in SpaceX in 2021. Oman planned its first satellite launch, from the United Kingdom, in early 2023, but the Virgin Orbit launch containing the satellite failed.

Kuwait launched its first satellite in June 2021, and Bahrain’s first satellite was put into orbit in December 2021, in cooperation with the UAE Space Agency. Bahrain will launch its first entirely “Made in Bahrain” satellite by the end of 2023.

GCC countries are looking to simultaneously partner with other states in order to advance their space objectives and focus on local manufacturing and human capital development. The Saudis and Emiratis both seek to be recognized as regional space powerhouses with national space industries that innovate and demonstrate economic diversification. As the space sector continues to become more commercially and politically significant across the globe, it will be important for these nations to consider the geopolitical implications of their space partnerships with other governments. One example of this is a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) that the UAE signed with China in September 2022 for the Rashid II rover to fly on the Chang’e-7 mission. Since then, it has been reported that the agreement conflicts with the U.S. government’s International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) and may not move forward as planned. The space industry is a sensitive one, and government leaders are increasingly taking notice of how cooperation in space between countries impacts relationships down on Earth.

Bayly Winder is a Non-Resident Scholar with MEI’s Strategic Technologies and Cyber Security Program and a Senior Associate at satellite startup E-Space, focused on international business development and government relations, with an emphasis on the GCC.

Photographer: Christopher Pike/Bloomberg via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.